HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

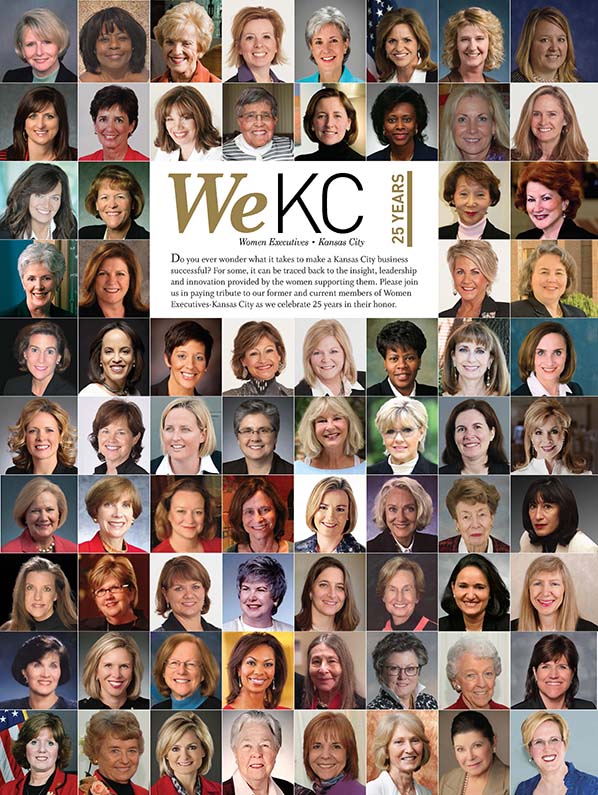

Nearly a quarter-century has passed since Ingram’s convened an assembly organized by and for women in executive roles, and programmed specifically around concerns of female executives in this particular market. That first gathering in 1993 was called Women Executives-Kansas City—WeKC, for short.

Over the course of time, as the numbers of women in the C-suites has increased—though not nearly in proportion with their share of the work force, or share of college degrees awarded—WeKC itself has changed. In 2002, Ingram’s modified the concept to create a recurring series of awards recognizing truly outstanding performance by women in executive roles. That tradition continues 15 years later with the 2017 Class of WeKC honorees.

Most interesting about the concerns of women in executive capacities today, perhaps, is how much they mirror the concerns that the previous generation expressed in an era that predated the Internet, the dot.com bust, 9/11, wars on terrorism, the housing and financial crises of 2008 and a recovery that took far too long to exert its influence.

What’s also interesting, as we stop to recognize the significant distances that women still must travel to attain a representative balance of executive power in commerce, is that the process has taken much longer than we might have anticipated.

Take, for example, Ingram’s coverage of the 2000 WeKC assembly, a gathering that focused strictly on leaders in K-20 education. Consider the implications of this passage:

“The days of no choices for women in the workplace are long gone. Those of us whose mothers told us, ‘Well, dear, you can either be a teacher or a nurse. It’s a good job, and you’ll always have it if you need it,’ tell our daughters something far different today. In fact, most of us, according to these distinguished women, are surprised when people do pick teaching as a career.”

Let that sink in: That hope-filled harbinger of change written nearly a generation ago. How far have we come from the “long-gone” days of limited

career choice?

Well, here’s one indicator: In that same year, precisely two women held the role of chief executive in the ranks of Fortune 500 companies. That came to less than half of 1 percent of those positions. As of the first quarter of this year, the figure is 5.4 percent, with 27 women in those leadership roles. Anyone who suggests that we should take a measure of solace from a 13 fold increase in the raw numbers surely brings to mind Mark Twain’s hierarchy of untruths—“there are lies, damn lies… and statistics.”

Any honest assessment of whether the doors of the C-suites have truly been opened to all, irrespective of gender, must recognize that as a nation, we still have a very long way to go to ensure equal access to each rung on the ladder of success.

“Is the disparity real? Absolutely!” says Lois Brayfield, owner of branding firm J. Schmid, and one of the inaugural honorees in the Class of 2002. “But I also have to wonder if women have also chosen to seek other honorable paths outside the work force that prevent a C-suite trajectory.” Stepping away from a career to have children, she said, puts them behind schedule in ways that new fathers rarely experience. “The good news,” she says, “is that as more women join the c-Suite, they will hopefully be more fair in their own management bias. Hopefully they won’t carry the same negative bias against other women.”

The dozen women featured in this year’s group of honorees demonstrates that there is, indeed, room on the ladder up. They hail from such varied sectors as manufacturing, consulting, health care, energy, hospitality, transportation, law and philanthropy, and they lead cornerstone companies in this region, and in their respective sectors.

A common theme for nearly all of them was the role that mentors played in their own successes. You’ll hear stories from these honorees about how those inspirational figures helped steer them to where they are today, and about how they, in turn, attempt to inspire and influence young women who show potential for executive leadership.

The need to meet and exceed expectations, though, will endure. As will our goal to recognize such performance.

As Lois Brayfield notes, “I believe that hard work, talent and pure tenacity still trumps all other road blocks for women. I’m not discounting the policies or amazing efforts that women have created to pave the way for others, but I was able to compensate for lack of opportunity with hard work and a willingness to never give up.”

Please join us in congratulating all those who have demonstrated that same tenacity as WeKC honorees, past and present.

Ann Konecny Foley Equipment Co.

As the third-generation leader of a family-owned business, Ann Konecny brought something to the role that set her apart from her father and grandfather: A woman’s perspective. In the world of heavy power equipment sales and service, that may indeed have been a distinguishing characteristic, but not an identifying one. “I was lucky that my father and grandfather encouraged me to be a leader in our family business in a day when that was not common for women in our industry,” says the CEO at Foley Equipment. Naturally, there would be challenges, but as Konecny notes, “people are more alike than they are different. I have not let being a woman in an industry dominated by men define me or my career. Everyone has obstacles and comes into contact with people who hold preconceived notions.” But true gender discrimination, in her experience, has been the exception, not the rule, she says. “I focus on the job and my work speaks for itself. I don’t think of myself as a female CEO, just like most men don’t think of themselves as a male CEO. I’m a CEO.” The company was founded in 1940 in Wichita, where Konecny spent most of her career and was a highly visible and engaged member of that city’s business leadership. It now has 19 locations in 14 cities, covering all but one Kansas county and 40 more in western Missouri, including the Kansas City metropolitan area. With the expansion into the Kansas City market, Konecny has taken her executive duties to a new level. “Our business has grown to the size where I must truly operate as a CEO,” she says. “I used to be much more deeply involved in day-to-day operations. My focus now is strategy and culture. Empowerment is an art, and I’m constantly working on improving how I manage the balance between empowering and abdicating responsibility.”

As the third-generation leader of a family-owned business, Ann Konecny brought something to the role that set her apart from her father and grandfather: A woman’s perspective. In the world of heavy power equipment sales and service, that may indeed have been a distinguishing characteristic, but not an identifying one. “I was lucky that my father and grandfather encouraged me to be a leader in our family business in a day when that was not common for women in our industry,” says the CEO at Foley Equipment. Naturally, there would be challenges, but as Konecny notes, “people are more alike than they are different. I have not let being a woman in an industry dominated by men define me or my career. Everyone has obstacles and comes into contact with people who hold preconceived notions.” But true gender discrimination, in her experience, has been the exception, not the rule, she says. “I focus on the job and my work speaks for itself. I don’t think of myself as a female CEO, just like most men don’t think of themselves as a male CEO. I’m a CEO.” The company was founded in 1940 in Wichita, where Konecny spent most of her career and was a highly visible and engaged member of that city’s business leadership. It now has 19 locations in 14 cities, covering all but one Kansas county and 40 more in western Missouri, including the Kansas City metropolitan area. With the expansion into the Kansas City market, Konecny has taken her executive duties to a new level. “Our business has grown to the size where I must truly operate as a CEO,” she says. “I used to be much more deeply involved in day-to-day operations. My focus now is strategy and culture. Empowerment is an art, and I’m constantly working on improving how I manage the balance between empowering and abdicating responsibility.”

Arzelia Gates Gates Bar-B-Q

Her work in the neat, stylish offices of Gates Bar-B-Q on The Paseo is a long way from those late nights counting change to assemble rolls of coins for the next morning’s bank deposits when she was still in high school, or hand-bottling barbecue sauce for her father’s restaurants.

Her work in the neat, stylish offices of Gates Bar-B-Q on The Paseo is a long way from those late nights counting change to assemble rolls of coins for the next morning’s bank deposits when she was still in high school, or hand-bottling barbecue sauce for her father’s restaurants.

But Arzelia Gates never forgot the truly important lessons she learned working for legendary barbecue baron Ollie Gates. Or in the years since, rising to her current position of Director of Community Relations for the business. “I’ve learned structure. In a family business there is one mission, so be committed to that mission and be faithful to that commitment,” she says. “And enjoy the journey, as things will come up and we don’t always have the answer at that time. But isn’t learning a part of the lesson?” When your last name isn’t just a name, but a brand, the magnetism of the family business exerts a powerful influence on career choices. A customer base that included figures like Pearl Bailey, Michael Jackson, members of the Kennedy clan—the list reads like a Who’s Who of American celebrity—made it an easy decision to stick with the company, which has six locations in the area, distributes sauce nationwide and has real-estate and other holdings. “My dad didn’t just build restaurants; his projects encompassed the whole area around each one, making them comfortable, secure, with landscaping and uniformity in the buildings,” she says. “He’s a historian, and his concept of neighborhood and community was always important to him, and still is for us.” Four members of Generation Four, including her daughter, are being exposed to those same life lessons and success keys. “We know where we fit in,” Gates says. “We’re a specialty restaurant with a few products we do well, but we give it all we’ve got, and that’s what sets us apart.”

Kathy Sudeikis Acendas

Untold thousands of people have benefitted from Kathy Sudeikis’ fine-tuned understanding of the travel sector, including a red-carpet lineup of screen and stage names like Anthony Quinn and Andrew Lloyd Webber. But how good is she, really? Good enough to book their travel when they’re dead, that’s how good. Early in her career, she chanced into a book of business for the traveling troupe with a performance of “The King and I” and ended up serving as travel agent for Yul Brynner, who had the starring role. When he headed to that Big Stage in the Sky in 1985, Sudeikis recalls, “I had to arrange to send his ashes back to France,” an undertaking—if we can use that word—fraught with its own comedic moments. Such is the life of catering to the rich and famous—and the Joe and Jane Averages—as one of the nation’s most-respected travel pros. She’s currently vice president for corporate relations at Acendas, the region’s biggest locally based travel agency, and is past president of the American Society of Travel Agents, a role that reinforced connections with travel pros and clients nationwide. That’s a far cry from this Chicago native’s first gig out of college. “A personnel agency sent me to be a junior accountant for the American Dairy Association,” Sudeikis recalls. “I promptly walked out to a travel agency on the corner of Wachter and Washington in Downtown Chicago and I asked, ‘How does one get into the travel business?’ She corrected that bit of miscasting and later moved to Kansas City with husband Dan, then set out to start booking $1 million-plus in travel annually while raising three kids who have gone on to succeed in film (Jason), education (Lindsay) and choreography (Kristin). In a long career of booking travel for others, she says, “there’s not a trip my clients have gone on where I didn’t want to go,” she says. “They walk out the door, and I’m almost in tears—I want them to take me, too!”

Untold thousands of people have benefitted from Kathy Sudeikis’ fine-tuned understanding of the travel sector, including a red-carpet lineup of screen and stage names like Anthony Quinn and Andrew Lloyd Webber. But how good is she, really? Good enough to book their travel when they’re dead, that’s how good. Early in her career, she chanced into a book of business for the traveling troupe with a performance of “The King and I” and ended up serving as travel agent for Yul Brynner, who had the starring role. When he headed to that Big Stage in the Sky in 1985, Sudeikis recalls, “I had to arrange to send his ashes back to France,” an undertaking—if we can use that word—fraught with its own comedic moments. Such is the life of catering to the rich and famous—and the Joe and Jane Averages—as one of the nation’s most-respected travel pros. She’s currently vice president for corporate relations at Acendas, the region’s biggest locally based travel agency, and is past president of the American Society of Travel Agents, a role that reinforced connections with travel pros and clients nationwide. That’s a far cry from this Chicago native’s first gig out of college. “A personnel agency sent me to be a junior accountant for the American Dairy Association,” Sudeikis recalls. “I promptly walked out to a travel agency on the corner of Wachter and Washington in Downtown Chicago and I asked, ‘How does one get into the travel business?’ She corrected that bit of miscasting and later moved to Kansas City with husband Dan, then set out to start booking $1 million-plus in travel annually while raising three kids who have gone on to succeed in film (Jason), education (Lindsay) and choreography (Kristin). In a long career of booking travel for others, she says, “there’s not a trip my clients have gone on where I didn’t want to go,” she says. “They walk out the door, and I’m almost in tears—I want them to take me, too!”

Melinda Estes Saint Luke’s Health System

No magnetic-resonance imaging, no CT scans, no 3-D imaging. When Melinda Estes was in medical school at The University of Texas Medical Branch—her initial goal was to be a pediatrician—neurology “required finesse, curiosity, and a level of communication with the patient that led to true connection,” she remembers. Prodded in that direction by neurologist John Calverly, it “opened up a new world to me, and I was hooked.” That’s how the daughter of a well-traveled Army officer ended up in medicine. But that was just the first step on a path that has taken her into executive roles, and ultimately brought her to Kansas City, as president and CEO of Saint Luke’s Health System. Encompassing multiple hospitals and care facilities across the region, the system admits more than 40,000 patients for care each year, and treats significantly more as outpatients. At each step on that journey, lessons from her father traveled with her. “My father, a three-war veteran, was always a driving influence and guiding force in my life,” she says. “I always had such deep respect and admiration for the person he was and the values he instilled in me.” He was also the one who encouraged her to find a career that would provide more stability than she might have found as a musician—a bassoonist, to be precise. “So I turned to science instead. And, as they say: father knows best,” she says. “It was a perfect fit for me.” And it’s paying dividends for consumers in this market. On her watch, Saint Luke’s has tackled the challenges of pivoting a health-care giant into compliance with the Affordable Care Act, embraced innovative technology (including online appointment scheduling and the Saint Luke’s 24/7 mobile app) and patient-centric models, implemented an electronic medical record

No magnetic-resonance imaging, no CT scans, no 3-D imaging. When Melinda Estes was in medical school at The University of Texas Medical Branch—her initial goal was to be a pediatrician—neurology “required finesse, curiosity, and a level of communication with the patient that led to true connection,” she remembers. Prodded in that direction by neurologist John Calverly, it “opened up a new world to me, and I was hooked.” That’s how the daughter of a well-traveled Army officer ended up in medicine. But that was just the first step on a path that has taken her into executive roles, and ultimately brought her to Kansas City, as president and CEO of Saint Luke’s Health System. Encompassing multiple hospitals and care facilities across the region, the system admits more than 40,000 patients for care each year, and treats significantly more as outpatients. At each step on that journey, lessons from her father traveled with her. “My father, a three-war veteran, was always a driving influence and guiding force in my life,” she says. “I always had such deep respect and admiration for the person he was and the values he instilled in me.” He was also the one who encouraged her to find a career that would provide more stability than she might have found as a musician—a bassoonist, to be precise. “So I turned to science instead. And, as they say: father knows best,” she says. “It was a perfect fit for me.” And it’s paying dividends for consumers in this market. On her watch, Saint Luke’s has tackled the challenges of pivoting a health-care giant into compliance with the Affordable Care Act, embraced innovative technology (including online appointment scheduling and the Saint Luke’s 24/7 mobile app) and patient-centric models, implemented an electronic medical record

system and opened several new clinics.

Denise Kruse AdamsGabbert

What makes Denise Kruse tick? Cookies. No, not eating them—thinking about what she learned selling them. “When I was in second grade, my parents couldn’t afford to send me to camp,” says the CEO at business consulting firm AdamsGabbert. “I asked the scout leader how I could go to camp, and she said by selling 267 boxes of Girl Scout cookies.” So she got out her bike, put boxes of cookies in the basket, and started canvassing door-to-door in Lincoln, Kan. And, no, she didn’t stop at 267 boxes. “I sold 272, just to make sure I had enough,” she remembers. “The greatest lesson was that I had a goal, I worked hard and could earn it. It didn’t mean that things would always work out that way—we don’t hit every goal we set our mind to, because other things in life get in the way—but it was the first really powerful goal that I could achieve.” Though her father, a United Methodist minister, couldn’t get her to camp, he imparted lessons of far greater value, Kruse says. “He had a significant promotion opportunity before my senior year in high school, but he declined so I could graduate with my friends; I look back and think about what a statement that was about him as a Dad. He was huge influence on me, living his faith without pushing it on others.” He was also extremely involved in efforts to improve the community, something that continues to resonate with her. After earning hear business degree at Emporia State, she worked in a number of settings before the opportunity came to join AdamsGabbert in 2012 and eventually buy it from the Bicknell family ownership. The company, after some organizational retooling, is back on a fast growth track in consulting, payroll services, recruiting, process improvements and other business guidance. One key, she says, “I’m a huge

What makes Denise Kruse tick? Cookies. No, not eating them—thinking about what she learned selling them. “When I was in second grade, my parents couldn’t afford to send me to camp,” says the CEO at business consulting firm AdamsGabbert. “I asked the scout leader how I could go to camp, and she said by selling 267 boxes of Girl Scout cookies.” So she got out her bike, put boxes of cookies in the basket, and started canvassing door-to-door in Lincoln, Kan. And, no, she didn’t stop at 267 boxes. “I sold 272, just to make sure I had enough,” she remembers. “The greatest lesson was that I had a goal, I worked hard and could earn it. It didn’t mean that things would always work out that way—we don’t hit every goal we set our mind to, because other things in life get in the way—but it was the first really powerful goal that I could achieve.” Though her father, a United Methodist minister, couldn’t get her to camp, he imparted lessons of far greater value, Kruse says. “He had a significant promotion opportunity before my senior year in high school, but he declined so I could graduate with my friends; I look back and think about what a statement that was about him as a Dad. He was huge influence on me, living his faith without pushing it on others.” He was also extremely involved in efforts to improve the community, something that continues to resonate with her. After earning hear business degree at Emporia State, she worked in a number of settings before the opportunity came to join AdamsGabbert in 2012 and eventually buy it from the Bicknell family ownership. The company, after some organizational retooling, is back on a fast growth track in consulting, payroll services, recruiting, process improvements and other business guidance. One key, she says, “I’m a huge

believer in providing feedback. Most people appreciate direct, honest feedback that’s not personally incriminating or disrespectful.”

Els Thermote TVH Americas

At age 27, Els Thermote came to America with a mandate from the family: Take control of the new operation. Co-founded by her father in 1969, the family business is TVH, a Belgian-based global provider of spare parts for materials handling equipment and industrial equipment. In 2003, after it had acquired its chief competitor, Olathe-based Systems Material Handling, TVH wanted its operations in the Western Hemisphere—all of it—to be under someone in the family. It wasn’t exactly taking a risk on a novice administrator: Thermote had held a seat on the company’s executive board since she turned 20, even before picking up her business degree and MBA. “Growing up in Belgium, being the daughter of the founder, people would make comments that “it is easy being the daughter of …’ although I worked really hard,” she says. But in the U.S., “I felt much more respected and could prove myself for my capabilities.” Those have been brought out with the help of key influencers. “I have been blessed to have had several mentors during my career, from my father to the executive team in place when I moved from Belgium to the USA,” Thermote says. Tony Lewis, her Vistage chair, was a particularly strong mentor for her eight years with that organization, she says, and combined with her experiences at YPO, “my main learning lesson has been to work ON the business instead of IN the business.” You can’t argue with the results: On her watch, the Americas operations for TVH have quadrupled in size, with sales growth of more than 600 percent and 2016 revenues of $350 million. Thermote understands that even in a sector tilted toward employing men, skill matters. “I have not encountered issues being a female in a male-dominated industry,” she says. “I believe that as long as you create a great employee and customer experience, it does not matter.”

At age 27, Els Thermote came to America with a mandate from the family: Take control of the new operation. Co-founded by her father in 1969, the family business is TVH, a Belgian-based global provider of spare parts for materials handling equipment and industrial equipment. In 2003, after it had acquired its chief competitor, Olathe-based Systems Material Handling, TVH wanted its operations in the Western Hemisphere—all of it—to be under someone in the family. It wasn’t exactly taking a risk on a novice administrator: Thermote had held a seat on the company’s executive board since she turned 20, even before picking up her business degree and MBA. “Growing up in Belgium, being the daughter of the founder, people would make comments that “it is easy being the daughter of …’ although I worked really hard,” she says. But in the U.S., “I felt much more respected and could prove myself for my capabilities.” Those have been brought out with the help of key influencers. “I have been blessed to have had several mentors during my career, from my father to the executive team in place when I moved from Belgium to the USA,” Thermote says. Tony Lewis, her Vistage chair, was a particularly strong mentor for her eight years with that organization, she says, and combined with her experiences at YPO, “my main learning lesson has been to work ON the business instead of IN the business.” You can’t argue with the results: On her watch, the Americas operations for TVH have quadrupled in size, with sales growth of more than 600 percent and 2016 revenues of $350 million. Thermote understands that even in a sector tilted toward employing men, skill matters. “I have not encountered issues being a female in a male-dominated industry,” she says. “I believe that as long as you create a great employee and customer experience, it does not matter.”

Tammy Peterman University of Kansas Health System

Tammy Peterman’s path to leadership didn’t incorporate a formal mentor/mentee structure; she got where she is today simply by absorbing vital lessons from key influencers. Lots of them. And she hopes to be doing the same for the next generation of leaders at the region’s largest academic medical center. A nurse by training, Peterman today wears several hats there—executive vice president, chief operating officer and chief nursing officer. Each thread woven into her duties, she said, represented lessons learned and absorbed. “I didn’t formally seek out a mentor, but over the course of time, I clearly had those connections,” she says. Foremost among them was her father, a doctor in western Kansas who touched other lives with a special blend of care and compassion. “He was a great influencer, not just in my career, but in my life,” she says. After joining the hospital three decades ago as a staff nurse, she encountered many others who helped shape the way she now sees patient care interacting with business administration. “They gave me some of those opportunities to grow in a way that I hadn’t thought about, and encouraged me and gave me confidence,” she says. She strives to make similar contributions in the lives of the generation that will succeed the current executive team. “Part of my responsibilities,” she says, “is to produce leaders of the future, many of whom are young women” in a sector dominated by female employees. A powerful demonstration of all she’s learned involves the new $370 million patient tower opening this month. Rather than interface throughout the project with the contractors and architects, she and the leadership team brought in the front-line staff and physicians who would use the building, offering direct, invaluable and detailed input that will help hands-on providers do their work.

Tammy Peterman’s path to leadership didn’t incorporate a formal mentor/mentee structure; she got where she is today simply by absorbing vital lessons from key influencers. Lots of them. And she hopes to be doing the same for the next generation of leaders at the region’s largest academic medical center. A nurse by training, Peterman today wears several hats there—executive vice president, chief operating officer and chief nursing officer. Each thread woven into her duties, she said, represented lessons learned and absorbed. “I didn’t formally seek out a mentor, but over the course of time, I clearly had those connections,” she says. Foremost among them was her father, a doctor in western Kansas who touched other lives with a special blend of care and compassion. “He was a great influencer, not just in my career, but in my life,” she says. After joining the hospital three decades ago as a staff nurse, she encountered many others who helped shape the way she now sees patient care interacting with business administration. “They gave me some of those opportunities to grow in a way that I hadn’t thought about, and encouraged me and gave me confidence,” she says. She strives to make similar contributions in the lives of the generation that will succeed the current executive team. “Part of my responsibilities,” she says, “is to produce leaders of the future, many of whom are young women” in a sector dominated by female employees. A powerful demonstration of all she’s learned involves the new $370 million patient tower opening this month. Rather than interface throughout the project with the contractors and architects, she and the leadership team brought in the front-line staff and physicians who would use the building, offering direct, invaluable and detailed input that will help hands-on providers do their work.

“At the end of day,” she says, “what I’ve benefitted from is the collective wisdom of a lot of people.”

Lisa Sackuvich ARJ Infusion Services

For two decades, Lisa Sackuvich labored to become a master of her particular health-care craft as a professional, skilled infusion nurse specialist. In her hands, a needle was an instrument of art. “Nursing was a vast and varied career path and I had an incredible nursing education at Avila University, as well as priceless nursing mentors along the way,” says Sackuvich. “Building and bringing together an organization of caring individuals to provide health-care services was my ultimate goal toward improving patient care.” After 20 years of working for others, she borrowed enough to take the entrepreneurial plunge in 2000, founding ARJ Infusion Services, based in Lenexa. Now, she’s an accomplished business executive, too. From that one-woman operation sprung a company that’s on pace to hit $100 million in revenues within the next few years. Sackuvich was convinced that people in need of infusion therapies—delivered by highly skilled nurses—would overwhelmingly choose to have those treatments in their own homes, at any hour of the day, if only there were a way. So she created that way, and today, ARJ has more than 80 employees treating patients nationwide. “Early in my childhood I experienced the health-care system as a young patient,” she says. “I was frightened and fascinated by those encounters at the hospital. Both of my grandmothers had sisters who were nurses. I loved hearing their stories about their nursing careers. I’ve always wanted to take care of people in their times of need.” ARJ does just that, treating patients of all ages with bleeding and neurological disorders, immune deficiencies or genetic disorders, or delivering IV antibiotics and other medications. Success has allowed her to help steer more than $2 million, through company, staff and personal philanthropy, toward various charities, including ones that serve children with hemophilia.

For two decades, Lisa Sackuvich labored to become a master of her particular health-care craft as a professional, skilled infusion nurse specialist. In her hands, a needle was an instrument of art. “Nursing was a vast and varied career path and I had an incredible nursing education at Avila University, as well as priceless nursing mentors along the way,” says Sackuvich. “Building and bringing together an organization of caring individuals to provide health-care services was my ultimate goal toward improving patient care.” After 20 years of working for others, she borrowed enough to take the entrepreneurial plunge in 2000, founding ARJ Infusion Services, based in Lenexa. Now, she’s an accomplished business executive, too. From that one-woman operation sprung a company that’s on pace to hit $100 million in revenues within the next few years. Sackuvich was convinced that people in need of infusion therapies—delivered by highly skilled nurses—would overwhelmingly choose to have those treatments in their own homes, at any hour of the day, if only there were a way. So she created that way, and today, ARJ has more than 80 employees treating patients nationwide. “Early in my childhood I experienced the health-care system as a young patient,” she says. “I was frightened and fascinated by those encounters at the hospital. Both of my grandmothers had sisters who were nurses. I loved hearing their stories about their nursing careers. I’ve always wanted to take care of people in their times of need.” ARJ does just that, treating patients of all ages with bleeding and neurological disorders, immune deficiencies or genetic disorders, or delivering IV antibiotics and other medications. Success has allowed her to help steer more than $2 million, through company, staff and personal philanthropy, toward various charities, including ones that serve children with hemophilia.

Heather Humphrey Great Plains Energy/KCP&L

Great Plains Energy, parent of Kansas City Power & Light, has roughly 2,500 employees, but can any of them be quite as busy as Heather Humphrey? She’s the general counsel and senior vice president for corporate services, overseeing legal operations, supply chain and human resources. And regulatory matters. And safety, security and facilities. Want more? She’s part of the utility’s senior leadership team and management-administration committee. And this St. Louis native also sits on the board of the Wolf Creek nuclear generating station near Burlington, Kan., which the utility co-owns. A strong work ethic underlies the performance that got her where she is, but look-ing back, she says, some key influencers contributed—including one who brought her into this world. “I’m lucky to have a mother who was a working mom,” says Humphrey. “She is retired now, but was a stand-out professional in the aerospace industry for her entire career. Not only did I get to experience her professional life when I was living at home but I have had the benefit of her professional counseling and advice throughout my own career. People pay career counselors a lot of money for the kind of insight and advice I have received from my mom. Fortunately, she’s never sent me an invoice!” At the professional level, Humphrey started as an associate at Shughart Thomson & Kilroy, which became a part of what’s known today as Polsinelli, PC. There, she aligned with a standout mentor in trial lawyer Karen Halbrook, in whom Humphrey saw a relentless attitude “to build the next generation of service-oriented, business-developing attorneys at that firm.” Practical advice that taught Humphrey the value of “service above all else, owning your future and not relying on others to provide, building something out of nothing. These principles stuck,” she says, “and I work hard every day to pass them along to others.”

Great Plains Energy, parent of Kansas City Power & Light, has roughly 2,500 employees, but can any of them be quite as busy as Heather Humphrey? She’s the general counsel and senior vice president for corporate services, overseeing legal operations, supply chain and human resources. And regulatory matters. And safety, security and facilities. Want more? She’s part of the utility’s senior leadership team and management-administration committee. And this St. Louis native also sits on the board of the Wolf Creek nuclear generating station near Burlington, Kan., which the utility co-owns. A strong work ethic underlies the performance that got her where she is, but look-ing back, she says, some key influencers contributed—including one who brought her into this world. “I’m lucky to have a mother who was a working mom,” says Humphrey. “She is retired now, but was a stand-out professional in the aerospace industry for her entire career. Not only did I get to experience her professional life when I was living at home but I have had the benefit of her professional counseling and advice throughout my own career. People pay career counselors a lot of money for the kind of insight and advice I have received from my mom. Fortunately, she’s never sent me an invoice!” At the professional level, Humphrey started as an associate at Shughart Thomson & Kilroy, which became a part of what’s known today as Polsinelli, PC. There, she aligned with a standout mentor in trial lawyer Karen Halbrook, in whom Humphrey saw a relentless attitude “to build the next generation of service-oriented, business-developing attorneys at that firm.” Practical advice that taught Humphrey the value of “service above all else, owning your future and not relying on others to provide, building something out of nothing. These principles stuck,” she says, “and I work hard every day to pass them along to others.”

Madeleine McDonough Shook, Hardy & Bacon

When Madeleine McDonough assumed command of the region’s largest law firm last year, she brought to the task multiple perspectives, not the least of them being that of a medical-arts practitioner. She was, in an earlier life, a clinical pharmacist. More relevant to the role of chair were views formed by drawing from influential figures in the field of law, and shaping her executive outlook today. “I had the benefit of being championed early and often in my career by the best in the business, and I still practice law today,” she says. “We tend to think of strategists, administrators and practitioners as mutually exclusive roles. I have learned from my mentors that all three perspectives are invaluable to helping our clients overcome their business challenges and find new opportunities to succeed professionally and personally.” What she’s learned as both mentor and mentee, she says, is that many firms rely on informal but established networks to distribute work throughout the organization. “As a result, many women attorneys wind up over-mentored but under-sponsored, without access to the traditional revenue streams that further long-term career growth.” At the same time, they are frequently called upon to speak to their own competence and experiences not only as individuals but as representatives of their gender, she says. Ponder that for a moment: When was the last time you heard a man assess his own career in a gender-based context? So among her varied duties, she steers the firm’s efforts “to interrupt these biases by creating a culture of psychological safety for our attorneys and developing inclusive leaders,” McDonough says. “We rely on metrics, not perception, to drive realignments in strategy and policy. And we partner with clients to mentor across firm and client lines through mechanisms like secondments, which are invaluable to building the types of robust networks that benefit both parties.”

Debbie Wilkerson Greater Kansas CIty Community Foundation

Sometimes, a mentor can be the first person you see when the alarm goes off in the morning. Ask Deb Wilkerson, whose gallery of key influencers starts with her husband, Kevin. “He has had a long career in commercial real estate, and he’s been quite successful in his own right,” says the president and CEO of the region’s largest philanthropic organization. “His approach is to never put your own interest in front of a client’s, no matter what. You might strive for success in some way, but you can never get there if you don’t put the folks you’re working for ahead of personal interests.” It’s a real plus, she says, when you’ve got someone within your own world who keeps you grounded, especially with two demanding careers and four children to balance. Before she entered philanthropy, Wilkerson practiced wealth-management law, including estate planning, at Shook, Hardy & Bacon. Right out of law school, she met Marie Woodbury, who taught her about the value of looking beyond a resume to find people who truly fit the mission. “She would give up a No. 1 in their law-school class who was ruthless and dry for a No. 10 who is friendly and well-rounded,” Wilkerson recalls. And in the philanthropy space, the foundation’s Jan Kreamer and George Bittner were “visionaries in the field and what it means to have your view on the horizon for what’s next,” Wilkerson says, “but at the same time, being able to build trust in the here and now.” Thus blessed, she strives to be a leader who can create a workplace that serves employees as well as community. “I don’t want anyone to think they have to take a back seat or a less-interesting career just to be good parent,” she says. “We want them to have interesting work that allows them to keep growing in the professional world, while at the same time allowing them to be the best parent they can be.”

Sometimes, a mentor can be the first person you see when the alarm goes off in the morning. Ask Deb Wilkerson, whose gallery of key influencers starts with her husband, Kevin. “He has had a long career in commercial real estate, and he’s been quite successful in his own right,” says the president and CEO of the region’s largest philanthropic organization. “His approach is to never put your own interest in front of a client’s, no matter what. You might strive for success in some way, but you can never get there if you don’t put the folks you’re working for ahead of personal interests.” It’s a real plus, she says, when you’ve got someone within your own world who keeps you grounded, especially with two demanding careers and four children to balance. Before she entered philanthropy, Wilkerson practiced wealth-management law, including estate planning, at Shook, Hardy & Bacon. Right out of law school, she met Marie Woodbury, who taught her about the value of looking beyond a resume to find people who truly fit the mission. “She would give up a No. 1 in their law-school class who was ruthless and dry for a No. 10 who is friendly and well-rounded,” Wilkerson recalls. And in the philanthropy space, the foundation’s Jan Kreamer and George Bittner were “visionaries in the field and what it means to have your view on the horizon for what’s next,” Wilkerson says, “but at the same time, being able to build trust in the here and now.” Thus blessed, she strives to be a leader who can create a workplace that serves employees as well as community. “I don’t want anyone to think they have to take a back seat or a less-interesting career just to be good parent,” she says. “We want them to have interesting work that allows them to keep growing in the professional world, while at the same time allowing them to be the best parent they can be.”

Gail Worth Gail’s Harley-Davidson

Yes, there is a team element linked to individual success. As was the case with Gail Worth, growing up in a family that ran a Harley-Davidson dealership. She had a head coach in her father, “the greatest businessman I ever met—I always wanted to be just like him,” she says. And her mother, Worth says, “was my greatest cheerleader. I probably got a lot of my compassionate side of business from her.” After starting as a part-time employee while still in high school, she went to work for her Dad in 1983 and spent 16 years studying the playbook before taking the ball and running with it. She bought it from him in 1999, acquiring one in St. Louis last year and another in Shawnee last month. “I started out as a secretary and moved up through the business,” she remembers. “Dad was an old-school guy: Nothing was given to you because you were his daughter.” Just the opposite, she says; “I had to work 10 times harder than anyone else just to move up ranks like an average person.” That she did, eventually earning the title of general manager. Nearly two decades in the business have convinced her of the soundness of career choice. “I love Harleys, I love the people, I love the executives at Harley,” she says. “Riders are so different than the average person—there’s a brotherhood like nothing else. I knew early on that I wanted to be a part of Harley and the cycle world in a big way.” She first pondered buying a dealership in Arizona, but her Dad said, “I’m going to retire and sell it for X-price. If you want it at that price, you can have it.” She then applied what she had learned from him. “Dad was very much down-to-business,” she says. “I don’t know if it’s because I’m a woman, I don’t know where it comes from, but I used Dad’s sense of business, and what I learned from Mom about the ability to work with people.”

Yes, there is a team element linked to individual success. As was the case with Gail Worth, growing up in a family that ran a Harley-Davidson dealership. She had a head coach in her father, “the greatest businessman I ever met—I always wanted to be just like him,” she says. And her mother, Worth says, “was my greatest cheerleader. I probably got a lot of my compassionate side of business from her.” After starting as a part-time employee while still in high school, she went to work for her Dad in 1983 and spent 16 years studying the playbook before taking the ball and running with it. She bought it from him in 1999, acquiring one in St. Louis last year and another in Shawnee last month. “I started out as a secretary and moved up through the business,” she remembers. “Dad was an old-school guy: Nothing was given to you because you were his daughter.” Just the opposite, she says; “I had to work 10 times harder than anyone else just to move up ranks like an average person.” That she did, eventually earning the title of general manager. Nearly two decades in the business have convinced her of the soundness of career choice. “I love Harleys, I love the people, I love the executives at Harley,” she says. “Riders are so different than the average person—there’s a brotherhood like nothing else. I knew early on that I wanted to be a part of Harley and the cycle world in a big way.” She first pondered buying a dealership in Arizona, but her Dad said, “I’m going to retire and sell it for X-price. If you want it at that price, you can have it.” She then applied what she had learned from him. “Dad was very much down-to-business,” she says. “I don’t know if it’s because I’m a woman, I don’t know where it comes from, but I used Dad’s sense of business, and what I learned from Mom about the ability to work with people.”