HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

In the 6½ years since the Federal Funds Rate hit its historic low of zero to 0.25 percent in January 2009, the goalposts on predictions for when the Fed would raise rates haven’t just been moved around the end zone; they’ve been relocated to other area codes: 2012, 2013, 2014…

After again refusing to budge at its September meeting, the Federal Reserve has inspired fresh speculation that it will raise interest rates as soon as December—(“and this time we really, really mean it!” the economic punditry says). For banks in the Kansas City region—who do, after all, make money by making loans—higher interest rates offer the prospect of higher earnings, thanks to potentially higher margins on loans. But it’s not like those banks have been sitting on their hands in the years since the Fed brought the rate tumbling to near zero.

In the wake of the Great Recession, the regional lending environment has seen significant recovery over the past five years. Using each June 30 as a baseline since 2011, the total aggregate volume of loans and leases among locally headquartered banks in this market is up more than 41 percent, surging from $25 billion to more than $36 billion this year.

In percentage terms, the biggest increases in lending categories market-wide have been: Municipal loans, up 156.43 percent; auto loans, up 149.28 percent; multifamily residential (1-4 units), up 97.37 percent; commercial and industrial lending, up 73.31 percent; commercial real estate, up 71.46 percent; farm real estate, up 52.44 percent, and farm loans, up 50.92 percent.

The lagging areas for lending included construction and land-development loans, which actually contracted from 2011 levels—hard to believe, perhaps, for anyone who was in the construction sector during those lean days. But even there, the market-wide lending volume has risen steadily, from $1.9 billion to $2.26 billion, after a big annual drop from ’11-’12, when lending in that category plunged from $2.45 billion to $1.89 billion.

Other laggard categories include consumer credit-card lending, down 2.83 percent since 2011, and other multifamily housing, down 9.23 percent. The latter, however, reflects the same pattern as construction and land development—a big one-year drop starting in 2011, followed by steady increases from $630.4 million in 2012 up to $720.6 million this year.

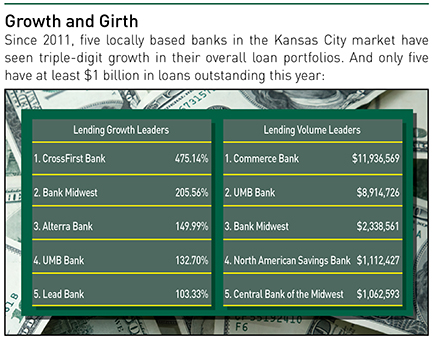

Among the total loans and leases of $36 billion market-wide, a dozen banks had lending portfolios of more than $400 million each. And within that group, the five biggest lenders—all with portfolios of at least $1 billion—accounted for $25.1 billion of loan volume. That’s 69.69 percent of all lending among local banks in the region.

All told, the dozen biggest lenders held $28.98 billion in loans as of June 30, accounting for 80.5 percent of the market volume. That left more than 70 smaller banks to chase the remaining 19.5 percent of lending in the region.

The kingpin in overall lending was Commerce Bank, with $11.79 billion on the books by mid-year 2015. UMB was the only bank within shouting distance of that, at $8.84 billion. Commerce strengthened its market-leading position by generating an additional $2.6 billion in loan volume over that period. And it didn’t get there, says Kansas City market President Kevin Barth, by taking chances.

“We believe in trying to be stable and consistent in decision-making, whether in good times or bad times,” he said. And that means following not the money, but the demand for it. “Even during the recession, loans in health care and health-care-related projects were growing like crazy—double digits every year through recession, because that’s where spending was taking place. They were continuing to invest and refinance debt when rates dropped.”

An abundance of caution on the residential development side, Barth said, helped the bank avoid the large losses inflicted on other financial institutions during the national real-estate bust. “We saw back in ’06 that residential lending was overheated, and we decided we needed to be more cautious and work with some developers to be more cautious. It was us working with customers we’d worked with a long time to make good, rational decisions.”

The commercial lending story reflects differences in the various lending models. There, UMB holds a commanding lead with $4.18 billion in commercial and industrial loan volume, ahead of the $2.81 billion reported by No. 2 Commerce. Bank Midwest ($638.22 million), CrossFirst Bank ($435.89 million) and Country Club Bank ($196.56 million), rounded out the top five in that category.

Tom Terry, chief lending officer at UMB, attributed strong performance in that and other categories to strategic hires and a focus on potential growth areas coming out of the recession.

“That period of time was very good for UMB, even if it was difficult for the industry,” he said. “We didn’t have a lot of the problems many competitors had.” While those banks were cleaning up their own affairs in 2011-12, UMB ramped up for the competitive lending landscape that has emerged since then. “It was more a focus on certain areas of the econ, building out commercial real estate is an example,” Terry said, pointing to new initiatives in investment CRE as well as in health-care lending. “And agribusiness has grown considerably, as well,” he said. “UMB has always been an active agriculture lender, but in the last two or three years, we’ve put more structure around that.”

As much as market share matters, so does growth, and nobody is mastering loan volume growth like CrossFirst Bank. Still less than a decade since its inception as Crosspoint Bank, it leads the pack with a five-year increase of 475.14 percent. That’s more than twice the growth rate of its nearest competitor, Bank Midwest, which logged an impressive 205.56 percent increase in overall lending. Next came Alterra Bank, the SBA’s reigning market champion for small-business loans; it posted an overall portfolio increase of 149.99 percent. UMB, with a surge of 132.7 percent, and Lead Bank, up 103.33 percent, round out the top five, the only banks in the market to record triple-digit overall lending growth.

Rising to that No. 1 spot was particularly impressive, given that CrossFirst wasn’t founded until 2007. CEO Mike Maddox pointed to one factor as the foundation of that ascendancy.

“It’s all about people,” he said. “We’ve been able to recruit some great talent, talented bankers who have been all about building relationships, and that’s where it starts. As we get bigger, obviously, our lending capabilities grow from a size standpoint, and that helps us grow from a volume standpoint. But we’re not doing anything differently today than in 2008, ’09, or ’10.”

Within the commercial/industrial category, 14 banks recorded triple-digit increases, with CrossFirst again leading the way: Among the lenders recording the biggest increase, CrossFirst notched a 676.78 growth rate through mid-2015. Close behind was Bank Midwest, with an increase of 614.90 percent, followed by 1st Cameron State Bank at 440.08 percent, Alterra Bank at 275.9 percent, and Adams Dairy Bank at 268.06 percent.

Bank Midwest’s position as one of the biggest lenders, as well as one of the fastest-growing, is rooted in the same factors Maddox cited. But it also benefitted from timing—NBH Holdings purchased the brand and major assets from Dickinson Financial Corp. in 2010, when a lot of other banks were pulling back.

“Since then, our focus has been on a client-centric relationship/new-business strategy, rather than a transaction strategy,” said Kevin Kramer, vice president for commercial lending at Bank Midwest. “For us, it was a focus on clients overall to help them achieve cash flow, and show how commercial loans can help them. That made us successful in attracting new clients to the bank.”

Commercial/industrial was a particular emphasis, he said, because of Kansas City’s strong business climate. “There are a lot of companies in our market that need that type of service in a relationship model, rather than a transaction model,” he said.

With the prospect of higher rates looming—presumably—where does that leave lenders? Essentially, they’re in a business-as-usual mode, and based on recent performance, that’s a winning strategy.

“It’s always out there, hot-and-cold that rates are going to change,” said Kramer. “Our success and growth as a company comes from being client-focused, not on what the Fed does with rates. In our economic environment now, we have to be ready for any movement in rates or compliance or political pressures, and try to minimize the effects from things we can’t control.”

Maddox sees the long-anticipated rate pop as an early 2016 development. “I think there are still too many moving parts, too much uncertainly, too much weakness,” he said. “Obviously, we’re a margin bank—a lot of banks are—so a little bump in rates would help our earnings. It would help a lot of banks. The financial sector is being hurt right now because of the low-margin environment.”

Despite the kind of growth seen in this market, he said, banks are still being cautious about extending any credit out too far. “They’re not locking rates in too far with what may happen going forward,” Maddox said. “We’re well-positioned if rates go up, and we’ll keep on trucking if they don’t.”

The effect of higher rates, said Barth, held the prospect of a dual benefit.

“Banks make interest income in two ways: off of loans and off of their bond portfolios,” he said. Higher rates benefit not just the loan margins, they allow banks to readjust and re-price bond portfolios at righter rates.

Beyond banks generally, Barth believes higher rates could yield some positives.

“I’m not an economist, but you wonder about the unintended consequences of keeping rates this low this long, and how that affects values, things getting over-valued,” he said. “Or peoples’ behavior, getting desperate and needing to get a return on cash, putting it in risky investments they do not fully understand.

“Most people would agree that rates should go up, but there’s fairly significant international pressure to hold them down. It will be interesting to see how the Fed will deal with it.”