HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Missouri’s entrepreneurial history was written by visionaries who didn’t just create legacies—they changed the world. And there’s more of it on the way.

No history of American entrepreneurship would be complete without a chapter—a thick one—on the achievements recorded by Show-Me State business visionaries. Starting with an inspiration, they produced generational wealth in consumer products, manufacturing, financial services, health-care, transportation and more.

Even after more than a century, their names live on, and in many cases carry on, through their descendants: Kemper. Danforth. Hall. Bloch. Taylor. McDonnell. Hunt.

Combined, their enterprises today generate hundreds of billions of dollars in corporate revenue, employ hundreds of thousands of people nationwide, and form the backbone of a state with 6.2 million residents and $344 billion in GDP.

And the litany of commercial conquest expands well beyond the state’s border. There’s even a Missouri component attached to names like Walt Disney, Sam Walton of Walmart and Jack Dorsey of Twitter—all spent their formative years in the state before going on to change the world in their respective spheres.

That history continues today, with companies flourishing in information technology, data storage and cybersecurity, logistics and distribution, agribusiness and advanced manufacturing, and more. If you can think of a business sector, you can find someone pushing the boundaries of innovation.

All of that is unfolding in ways that make Missouri one of the most inclusive environments for entrepreneurs. St. Louis, in recent years in fact, has been ranked No. 1 among U.S. cities for the share of start-ups headed by women, and Kansas City has also earned Top 10 status in that same metric.

In the Beginning…

One develops a healthier appreciation for 21st-century entrepreneurship by pausing to look in the rear-view mirror for a bit. Would today’s entrepreneurial ecosystem exist in its current form without the success and the inspiration of those who laid that foundation?

Among the earliest of the visionaries were Eberhard Anheuser and his son-in-law, Adolphus Busch. Following the latter’s Civil War service, they collaborated on a neighborhood brewery in St. Louis. It’s still that—if you define “neighborhood” today as the whole world because the enterprise they created would eventually become the biggest brewer on the planet.

At almost the same time, lumber magnate Francis Long established what would become Commerce Bank in Kansas City. It sold in 1881 to William Woods, whose granddaughter Gladys would marry William Thornton Kemper, setting the stage for that family’s six-generation run at the helm of two banks that today are among the state’s five biggest commercial banks: Commerce Bank and UMB Bank, with a combined $75 billion in assets.

As the recovery from the Civil War moved into its second decade, George Warren Brown found St. Louis to be fertile ground for manufacturing shoes, a sector that was then largely confined to the nation’s northeast. Brown Shoe Co. would thrive over the next 140 years, eventually rebranding as Caleres in 2015 and recently approaching $3 billion in sales.

The latter years of the 19th century produced another seedling for global growth when J.P. Leggett and future brother-in-law, C.B. Platt, began manufacturing a spring-based bed mattress in 1883. Still thriving today as a maker of beds, recliners and other furnishings and products, Leggett & Platt is both a commercial and manufacturing anchor in southwest Missouri. Based in Carthage, it had global revenues of 4.75 billion last year.

Back across the state a decade later, William Danforth and two partners saw a growing Midwestern agricultural sector ripe with opportunity for an animal-feed supplier. Their company soon adopted the Ralston-Purina brand and became a national player not just in pet products, but cereals for the breakfast table. More than that, it spawned multiple generations of civic-minded leadership, including a university president and a U.S. senator, on its way to a 2001 acquisition by European conglomerate Nestle for more than $10 billion.

Before the 1800s closed out, Henry J. Nicolaus and Herman C. Stifel teamed up in St. Louis to launch a financial services and investment company that bore their names. Today, Stifel is a holding company whose portfolio includes the biggest bank in the state, ranked by assets held.

The 20th century had just arrived when John Francis Queeny founded Monsanto in 1901 (he named it after the family of his wife, Olga). It went on to become a global maker of pesticides, herbicides and other chemical blends before a disastrous series of lawsuits related to health hazards from its Roundup herbicide prompted a 2018 sale to German titan Bayer for a whopping $66 billion.

Just a few years later, 19-year-old J.C. Hall came to Kansas City from his native Nebraska, carrying with him little more than two shoeboxes full of greeting cards. That was in 1910, putting him on course to create what today is a $3 billion global leader in greeting cards, personal expressions and entertainment.

In 1922, Edward Jones Sr. started a small investment brokerage house that would, in its space, democratize the accrual and management of personal wealth.

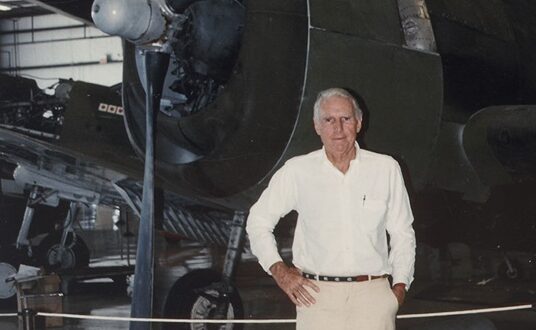

On the eve of World War II, aviation pioneer James McDonnell founded an aircraft company in St. Louis, and the demands of a nation at war—not simply for combat materiel, but for innovation in the production of it—proved to be a huge success factor. Just six years after start-up, McDonnell Aircraft Corp. was making aviation history with the successor to propeller-driven fighter planes; as the curtain closed on the war, it produced the first jet fighter to successfully take off and land on an aircraft carrier, setting the stage for nearly 80 years of geopolitical change in military strategies and muscular foreign policy.

As the middle of the century approached, a Kansas City pharmaceutical salesman named Ewing Kauffman decided to head out on his own with an enterprise he called Marion Labs in 1950. That branding offered a patina of scale to an operation he started at his home and turned into a nearly $6 billion acquisition target by Dow Chemical in 1989—a transaction that instantly infused the Kansas City area with 300 millionaires who had been Marion Lab employees.

A few years later, not far away in Kansas City’s Midtown, Henry and Richard pivoted from their roots as an accounting firm to become specialists in tax preparation. After initially offering the service for free to their accounting clients, they realized the hidden value in it. From there, it took less than a decade to go public en route to becoming the world’s best-known name in tax services.

A few years later, not far away in Kansas City’s Midtown, Henry and Richard pivoted from their roots as an accounting firm to become specialists in tax preparation. After initially offering the service for free to their accounting clients, they realized the hidden value in it. From there, it took less than a decade to go public en route to becoming the world’s best-known name in tax services.

And in 1957, Jack Taylor cobbled together a “fleet” of barely half a dozen vehicles to rent out—perhaps one of the nation’s first examples of what we now call the shared economy. Before he died in 2016, he not only had built one of the world’s largest leasing companies, Enterprise, but also paved the way for the acquisition of the competing Alamo and National brands. He also became a legendary philanthropist with gifts that easily topped $250 million before his death in 2016.

Carrying It Forward

The factors that led to the success of many of those established companies came into play over the past half-century as the state’s economy underwent some profound changes.

Perhaps the best example of that is St. Louis-based Centene, the state’s only representative on the Fortune 100, where it ranked 22nd this past cycle with annual revenues of $154 billion. That’s a very long way from its 1984 founding as a non-profit Medicaid provider in Wisconsin by former hospital bookkeeper Betty Brinn. A little more than a decade later, Michael Neidorff was brought on board as president and CEO, and the change was both immediate and swift.

First came the rebrand to Centene from the more prosaic Managed Health Services, in tandem with the corporate relocation to St. Louis. That was in 1997. Four years later, he orchestrated the initial offering of stock to take the company public, and the floodgates were open. Today, it’s the nation’s largest managed-care organization.

The St. Louis region further flexed its muscles in the health-care sphere with the 1986 consolidation of two companies that created Express Scripts. Under co-founders Howard Waltman and Joe Lynaugh, Express Scripts set out on a journey that has made it one of the nation’s biggest pharmacy-benefit managers, providing services to more than 85 million people and racking up $195.3 million in revenue last year.

St. Louis also produced what today is the nation’s largest minority-owned business, World Wide Technology, founded in 1990 by Dave Steward and James Kavanaugh. Steward leveraged that IT services provider to amass a personal fortune estimated by Forbes as more than $6 billion, ranking him No. 1 among the nation’s black business owners. WWT, now led by Kavanaugh, generates more than $20 billion in annual revenue.

Closer to consumers—and their appetites—is Panera Bread, which was the inspiration of Ken Rosenthal in St. Louis back in 1987. With a single sourdough starter secured from San Francisco, he launched St. Louis Bread Co., selling it just six years later for $23 million. Following a rebrand, CEO Ron Shaich set the stage for spectacular growth that led to more than 2,200 locations nationwide, operations around the world, and global sales topping $6 billion last year.

From Springfield came the O’Reilly family, whose small network of auto-parts stores was founded in 1957 but didn’t attain its status as a North American titan in that space for decades. The chain was 32 years old when it opened its 100th store in 1989 and has rocketed ahead from that point to today’s publicly traded company with more than 6,000 retail locations across North America and $15.8 billion in revenue.

Springfield also saw young Johnny Morris start to sell bait and fishing gear from the back of his father’s liquor store in the 1970s, then steadily build an empire created on a culture that celebrates outdoor recreation and activities. Unlike others at his level—he’s consistently ranked among the wealthiest people in Missouri—Morris never took Bass Pro Shops public. As a private company, it has 200 stores nationwide, with 80 stores carrying the brand of former arch-competitor Cabela’s, which sold to Bass Pro in 2017 for $5 billion. Its 40,000 employees generated an estimated $6.5 billion in sales last year.

Yet another Springfield company rising to national prominence from a bare-bones start is Prime, Inc. Young Robert Low began hauling freight with a single truck in 1970 and set about steadily increasing the reach of the company while sharpening its focus primarily on refrigerated truck transport. Fresh and frozen meat and produce, flowers, pharmaceuticals, beer, and juices fill more than 11,700 refrigerated trailers pulled by 6,500 trucks. How has that worked out for Low? His Primatara mansion in Greene County, covering 60,000 square feet, carries an assessed value of more than $70 million.

Kansas City, as well, has been a cradle of entrepreneurs over the past 50 years. It had barely become an incorporated municipality in the mid-19th century when visionaries with names that are now both iconic and generational began setting up shop: The Kemper family in banking (Commerce and UMB banks). Towering figures of engineering with names like Burns, McDonnell, Black and Veatch. The Hall family in greeting cards and creative services. Not long after the city’s centennial celebration, Richard and Henry Bloch started an enterprise that became the world’s biggest brand in tax-preparation services.

Over the past half-century, Kansas City has seen some spectacular corporate successes, with institutions that have formed and taken on global dimensions. Others have become the biggest and the best of what the business infrastructure there has to offer, only to be swept up by larger global players with bottomless pockets and seemingly insatiable appetites for acquisition.

The bottom line: Kansas City continues to boast a powerful roster of historical business figures who, at various levels, have built on the legacy gifted to them to cast their influence across regional commerce and, in some cases, around the planet.

Some of the major entrepreneurial figures from the past half-century include Ewing Kauffman, who made his fortune building a pharmaceutical company he founded as a one-man entity, then leveraged a fortune made in that field to help Kansas City regain pro-baseball status by founding the Kansas City Royals. In less than a decade, the team would make three runs at the American League pennant, each time bringing to mind the reason why a stage play that debuted in 1955 was titled “Damn Yankees.”

Lamar Hunt, hailing from a Texas oil family fortune, founded the American Football League in 1960 and three years later moved his team from Dallas to Kansas City. But his influence did not end on the field. Hunt Midwest, the real estate development firm he created, has become a monster in logistics development (and was the original owner of Worlds of Fun).

Perhaps the biggest entrepreneurial success of the past half-century was spawned by three executives from the Arthur Andersen accounting firm who envisioned a health-care IT service that would eventually become Cerner Corp., a multi-billion-dollar business by the time it was acquired in 2021 by Oracle.

That 50-year span also proved transformative for United Utilities, which had been incorporated in 1938 in Kansas, fully 40 years after its more humble beginnings as Brown Telephone Co. in Abilene, Kan. It would morph into United Telecom in the 1970s, which formed a partnership with another communications company to create U.S. Sprint in 1986. From there, we saw Sprint Nextel, then Sprint, on its rise to being the Kansas City area’s biggest private-sector employer—a distinction that faded over the past decade as Sprint was eventually sold to T-Mobile.

In a rather bold move, considering that Missouri was already home to the nation’s largest brewery, a young John McDonald launched Boulevard Brewing Co. in 1989. It quickly established a reputation for authentic hand-crafted ales and ushered in Kansas City’s microbrewery phase, though it wouldn’t be long before it dropped the “micro.” It became one of the nation’s biggest regional brewers before selling to a European firm in 2013 for a reported $36 million.

The decade also saw the emergence of Inergy LP, a propane-transmission service that helped energy executive John Sherman amass a fortune and, a generation later, prove instrumental in pro baseball circles with the purchase of the Royals in 2016.

Then there was the example of Jack Lockton, who began selling insurance from a spare bedroom of his Kansas City-area home in 1966. He charted a course for nearly unparalleled entrepreneurial success in the city, then the state, and finally on a global stage, as Lockton Cos. today is the world’s largest privately owned independent insurance brokerage. Until his death in 2004, he led the company to nearly four decades of year-over-year revenue increases, a pattern that has held up for the past 20 years, leading to 2023 revenues of $3.55 billion.

The ’90s also saw the rise of powerful changes in equities trading, thanks to the transformational work of Kansas City’s Dave Cummings with the founding of Tradebot Systems. It broke new ground in high-frequency, high-speed equities trading and later helped him bootstrap BATS Global markets in 2005. The latter would eventually overtake NASDAQ as the nation’s second-largest trading platform before selling in 2017 for a tidy $3.4 billion.

Further innovating the financial services landscape was a former A.G. Edwards & Sons adviser, Marty Bicknell, who launched Mariner Wealth Management in 2006. Through a savvy combination of timely, strategic acquisitions and organic growth, he turned it into one of the nation’s top five advisories for multiple years running, according to Barron’s.

Blue-collar entrepreneurship took a back seat to no other brand during the decade as the Ross siblings, led by Fred Ross as CEO, turned Custom Truck One Source into a national powerhouse in heavy construction equipment, setting the stage for a nearly $1.5 billion sale in 2020.

And the beat goes on in the 2020s, as banking scion Sandy Kemper sets volume records almost daily with his C2FO, a global accounts-payable management platform that, since its founding in 2008, has provided more than $300 billion in business funding for clients. The spectacular performance in fintech has created industry buzz about an initial public offering of stock that could create another Kansas City superstar company.

If that happens, he’d be bringing things nearly full circle with his family’s entrepreneurial history: He’s a sixth-generation descendant of the Kemper clan that laid the foundations for banking in Missouri.