HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

By Dennis Boone

A looming presidential election cycle. Huge market gyrations. Incessant talk about an inevitable recession. Mideast drone attacks crimping global energy supplies and spiking prices. Anyone who can read those tea leaves and get an accurate sense of where the U.S. economy is headed should be picking next week’s Powerball numbers.

For one group in particular, though, those elements underpin a nearly existential-level question: Business owners, who must ask themselves whether the time is now, whether this is the year, to sell their companies.

It’s not just a question for a comparative few. Because the Baby Boom produced the largest generation in U.S. history when it arrived, America nearly 75 years later is seeing the greatest volumes of business sales in its history. Millions of family-owned businesses are generating unprecedented levels of activity in the capital markets as those owners cash out on half

a century of building their enterprises.

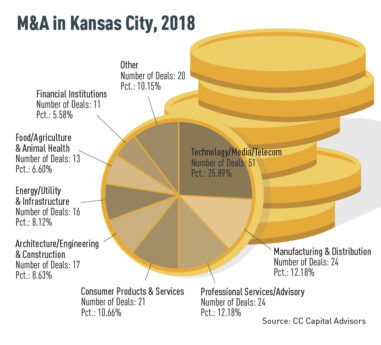

Diligently tracking that activity is CC Capital Advisors, an operating unit of Country Club Bank, which issues an annual report on merger-and-acquisition activity in the region. In 2018, the region fell just short of 200 such deals, but nonetheless set a record with 195 transactions. That was the highest since the firm began compiling those statistics 15 years ago. Nationwide, the numbers have backed off somewhat since hitting a record 2,705 in the second quarter of 2018, but remain above any period through the end of 2017, according to BizBuySell.com.

Diligently tracking that activity is CC Capital Advisors, an operating unit of Country Club Bank, which issues an annual report on merger-and-acquisition activity in the region. In 2018, the region fell just short of 200 such deals, but nonetheless set a record with 195 transactions. That was the highest since the firm began compiling those statistics 15 years ago. Nationwide, the numbers have backed off somewhat since hitting a record 2,705 in the second quarter of 2018, but remain above any period through the end of 2017, according to BizBuySell.com.

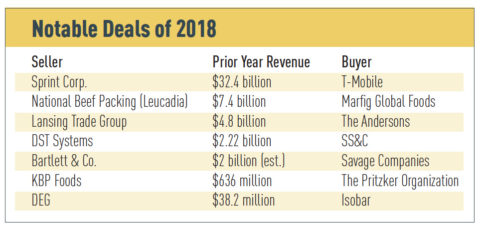

The biggest names in regional business get all the attention and headlines. They also skew the overall deal dollars northward for the group—Sprint, by agreeing to a $26.5 billion merger with T-Mobile; DST Systems, bought by SS&C Technologies for $5.4 billion, and Bartlett & Co., which sold off after a century to Savage Cos., reportedly for $3.5 billion.

But there were 192 other deals in this region, most of them involving small and mid-size business with revenues below $25 million a year. We haven’t seen that level of activity since 182 acquisitions in 2007, just ahead of the Great Recession. Anyone looking to sell and analyzing

the economic fundamentals in the run-up to that slowdown has to be wondering: “How will another recession affect my timing, and the price I might get?”

To a degree, those concerns are warranted, says John Hense, managing director for CC Capital Advisors. “A lot of what drives M&A activity is what I call corporate confidence, like consumer confidence drives consumer spending,” he said. “Corporate confidence, CEO confidence, drives M&A because buying a company is risky, obviously. When we have major swings in the markets, that tends to have an impact.”

But there are many other factors that determine whether the time is right to sell, business consultants say. Some of that has to do with a seller’s proven profitability, even in the face of a sluggish economy. Some has to do with the business sector of that seller’s company. Some—especially with high-performing small companies—has to do with personnel issues and a buyer’s ability to retain the talent has been vital to success.

The good news for sellers, Hense said is that “valuations for private companies today are as high as they’ve ever been, and that does not seem to be changing. When we have wild swings in the markets, the group of buyers that gets most impact would be strategic buyers, corporate buyers.” The private equity side, he said, accounting for about 30 percent of all activity in the U.S., helps keep thing stable because there is so much capital to deploy these days.

In the short term, business brokers say, companies hurt by lower interest rates (think community banks and their lending) or by trade issues in the ongoing tariff battle with China, those are the ones who could see their values dip in the short-term, a signal that they might not want to sell just yet. The same goes for those who feel their tax exposure would go up under, say, the administration of a President Elizabeth Warren.

Still, those business consultants say, with trillions of dollars chasing deals, valuations remain as high as ever, and it remains a seller’s market out there.

Still, those business consultants say, with trillions of dollars chasing deals, valuations remain as high as ever, and it remains a seller’s market out there.

A newer wrinkle in that cash infusion is the explosive growth in global wealth, over the past decade, and that wealth is seeking out opportunities to invest for the longer haul. “We’re absolutely seeing more foreign buyers,” Hense said. “We were hired a year ago by a European company that had a mandate to grow in the U.S. Their consensus was that Europe was not growing, but the U.S. is, so they needed a U.S. footprint. And we sold a KC-based company to a Canadian buyer backed by London private equity. We’re seeing more foreign interest, mainly because the U.S. is still regarded as a growth engine.”

The key for sellers trying to exploit those trends is having their financial ducks lined up, with current tax and regulatory filings available for review and books up-to-date.

“What a buyer looks for is growth and profit,” Hense said. “If you’re growing and have a good margin, more than likely, based on your size—and size is always a factor as well—you are going to get what we call a premium price for your company.”

Business brokers generally agree that because there is so much money available, investors are willing to accept slightly lower returns on their capital in order to get a deal done, and because of that, are willing to pay higher valuations. But they are especially interested in acquiring companies that are scalable, especially those in the tech sector, and those companies that can leverage tech advances to achieve significant growth. That added risk, brokers say, means the due diligence of buyers has taken on a new rigor.

So if valuations are high and demand is exploding, why aren’t owners everywhere cashing out? It’s a question brokers get all the time, and one answer is: Most owners, especially those who have spent decades enjoying double-digit returns on their equity, look around at investment opportunities today and balk at the prospect of far lower income on the capital realized from a sale.

“They have a hard time replicating that annual cash flow after they sell,” Hense said. “We have seen a little bit of that pushback.”

One other factor at work: The Boomers, for all the aches and pains of aging they are experiencing, are collectively healthier than any generational cohort before them, and they’re living longer. If they sell even at age 70, many can expect to live 10 or 15, even 20 more years, so having a bigger nest egg at cash-out, or having fewer years of life expectancy to cover, is also holding back some sales.