HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

The second quarter of 2020 is in the books, and it will go down as a historic three months for American business, American banking—and eventually, the American taxpayer. The latter will be on the hook for trillions in money borrowed to stave off the economic calamity of the COVID-19 global pandemic.

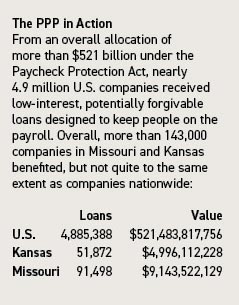

A major pillar of that spending was the Paycheck Protection Program, just one piece of the CARES Act passed by Congress in late March, as millions of workers were being laid off, furloughed or scaled down in salaries and hours at work. The program included two phases, the first of which was depleted of its funding within days of the program’s launch. Given the ravenous demand for that assistance, it’s somewhat surprising that the add-on PPP had $130 billion still available through the end of June.

For more than 143,000 companies in Missouri and Kansas, the assistance was a lifeline. It won’t be enough to ensure that all will survive a self-imposed national recession, but the money in general found its way to most of the companies facing the greatest challenges, regional bankers say. In doing so, the program overcame a hectic start, but achieved most of its broader goals.

“The first couple of weeks of the program were rocky, as rules were issued, changed and then finalized,” says Paul Holewinski, president and CEO of Dickinson Financial Corp. “Those were hectic times as the process was being built out, as banks, clients and the SBA were all trying to figure out how to get loans/grants to businesses to avoid a cascade of small business bankruptcies.”

Well over half a trillion dollars found its way to those companies, but the true test is yet to come, Holewinski said. “I believe the more challenging part of the program awaits, as banks and clients work to apply the forgiveness rules to the loans that were made. While recent SBA rule changes that extended the Covered Period and provided greater flexibility in use of proceeds that qualify for forgiveness, more is needed to simplify the process.”

Commerce Bank President Rob Bratcher believes that, on balance, the money ended up where it needed to, despite the rough start. “You had the Treasury driving this, trying to leverage the SBA, but the SBA was never really built to administer anything close to that type of lending volume,” Bratcher said. “Given the circumstances, I think it went as well as it could, but there was a lot of frustration in terms of the way guidance was coming out for lenders. A lot of us were trying to work together to urge the SBA and Treasury to at least spend a little time thinking through the areas that could be potential pitfalls or put out better guidance.”

Commerce Bank President Rob Bratcher believes that, on balance, the money ended up where it needed to, despite the rough start. “You had the Treasury driving this, trying to leverage the SBA, but the SBA was never really built to administer anything close to that type of lending volume,” Bratcher said. “Given the circumstances, I think it went as well as it could, but there was a lot of frustration in terms of the way guidance was coming out for lenders. A lot of us were trying to work together to urge the SBA and Treasury to at least spend a little time thinking through the areas that could be potential pitfalls or put out better guidance.”

Tom Terry, chief credit officer for UMB Bank, saw a number of positives come out of the program, including the speed that opened the spigot, the add-on funding, and the positive re-employment numbers that followed. “I also believe that PPP is a significant factor in why (thus far) Commercial Real Estate (particularly Multi-Family) has not been hit as hard as expected,” Terry said. “Though this may change as the COVID-19 recovery is slowing down and a pause in reopening the economy is occurring.”

The flip side of it, he said, was the lack of sufficient funding at the outset. “This approach created a gold-rush mentality and put tremendous pressure on the banks to process these loans quickly,” he said. “Congress should have communicated that there would be enough money for all “qualified” applicants and many of the frustrations from both the borrowers and the banks would have been lessened if not eliminated.

As challenging as it was for lenders, the program created riddles that business executives are still trying to resolve.

“When you get to ground level and talk with small business owners, the biggest thing they struggled with was the set of restrictions on the money,” Bratcher said. “Everyone wanted to save as many jobs as we could, but there are so many other expenses than just payroll. … But there definitely are some small companies that, regardless of the stimulus, may not be able to ever recover.”

Figures from the Small Business Administration show that, among the Missouri companies receiving assistance, the average loan came to slightly more than $99,000. On the Kansas side, it was a bit lower at $93,000. In each case, companies in the region lagged behind counterparts nationwide, where the overall average loan was more than $106,700.

“I believe that the program worked as intended to reach those small businesses most in need,” Holewinski said. “In the PPP loans that Academy Bank made, over 91.2 percent of the loan amounts were less than $350,000 and over 60.4 percent were less than $50,000.” That, he said, helped a lot of local small businesses keep workers employed. And with funds still available for use, he said, that “seems to indicate that the PPP program nationally reached the right eligible businesses in need.”

Given where business is after the capital infusion, and where the economy stands with the Fed essentially vowing to hold interest rates near zero through 2022, what will be the impact on banks? “That’s a great question and is largely dependent on the pace of the reopening,” Terry said. “The early signs were somewhat positive with an improved jobs report and increased economic activity. The recent increase in positive COVID-19 cases has created a pause in the reopening in some markets and a pullback in other markets. If that scenario is prolonged, then lending volume would decrease.”

Some sectors will pull through this stronger than others, so it’s a certainty that many lenders will be lasering in on companies that operate in what’s considered an essential industry, especially those with strong balance sheets and a history of performance in unsettled times.

“There are also many sectors that are challenged in this environment,” Terry said. “Industries that are negatively impacted by prolonged high unemployment would be challenged. Those would include hospitality and possibly certain segments of commercial real estate. Another industry that is impacted is aerospace. Also dependent on the pace of reopening and travel.”

And any company that does work for municipalities, as with road work, he said, “could certainly be negatively impacted in the next one to three years due to reduced tax revenue caused by COVID-19 and the quarantine. Construction is also an industry that is currently performing well, but could suffer from a prolonged slowdown and really feel that impact in 2021 and beyond.”

For those companies who are open again, but trying to calculate how to make their revenue model work with floor plans that may scale back customer density by half or more, Holewinski offered some advice:

“Communicate, communicate, communicate,” he said. “This mantra works well in good times and bad. Talk with your banker and help them to understand how your business is being impacted so the banker can respond to help with the financial tools at their disposal. The specific fallout of the pandemic isn’t still fully known at this point, but bridging the time between now and then will certainly require collaboration with your bank.”

A business impacted by COVID-19 that is not actively managing its situation with the help of its financial partners, he said, will likely recover much slower and suffer longer lasting impacts from the pandemic than one that is engaged with an active dialogue. “The community banking model built on relationship banking has never been more important,” Holewinski said. “Lean on your banker to help in these times.”