HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

For half a century, Kansas City has been defined by growth and change. In 2024, we’ll explore how it all came together.

PUBLISHED JANUARY 2024

It’s January 1974. Ingram’s magazine doesn’t yet exist. The seeds of intellectual capital for it, however, are about to be sown.

Over the coming decades, and into this, the 50th year of this enterprise, the story of a city’s business growth and executive leadership began to unfold, one monthly issue at a time. In 2024, as Ingram’s charges into the final year of its first half-century, we’ll take the measure of what has changed, how life has improved in this community, note the figures most responsible, and look ahead to the next 50 years.

But first, back to that first December’s publication in 1974. Outlook magazine hit the newsstands—remember those?—that month, with a promise of bringing a new kind of business journalism to a city, marking a period of dizzying advances.

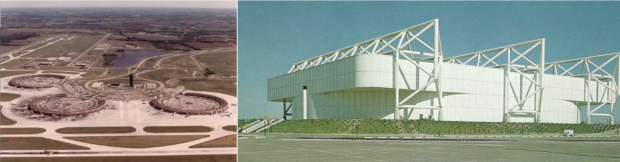

The “new” had yet to wear off on an international airport that is barely a year old; when it opened in 1972, KCI dazzled the aviation world with an innovative three-terminal configuration. It boasted one of the most efficient models anywhere to move people from arrival to departure gate and vice versa. The curtain had barely closed on Arrowhead’s debut of the Chiefs 1972 first season there. Royals Stadium, later rebranded in a tribute to the baseball team’s owner, had just completed Year One.

Barely two months before that first issue, the West Bottoms of Kansas City took on a new life as the doors opened for R. Crosby Kemper Jr. Arena, which immediately entered the host-city competition for a presidential party convention. It delivered on that promise in the very next election, two years later, as the site of the 1976 Republican National Convention.

Into this dynamic mix entered Outlook, and for seven years, it delved into business reporting under that brand before it morphed into Corporate Report Kansas City in 1981. Then, in October 1989—local lore holds that the change was influenced by Steve Forbes’ business- publishing success—the magazine went through its final rebranding in a tribute to then owner Bob Ingram, with the legendary Bo Jackson gracing that first cover. Michelle and Joe Sweeney took the riens in February 1997 and have owned and operated Ingram’s since.

Throughout the year, Ingram’s 50th volume will take you back to those years and the ones since. It’s our belief that we’ll never be able to build the city we hope this can be if we surrender our understanding of how we got where we are today—and how challenging and rewarding that journey has been.

In the coming months, we’ll break down in detail and decadal increments, the business deals that would re-create a regional economy, double the population of a metro area, stretch our concept of “suburbs” from 75th and Metcalf to 151st and K-7 Highway in Johnson County, well past that new airport in the Northland, pushing to the Lafayette County line on the east and into the far reaches of Jackson County’s southeastern quadrant, eventually creating a 318-square-mile community of … communities.

Here’s our plan for coverage in the coming year:

February: We’ll wrap up the 1970s by diving into the people and projects that remade this region on multiple levels. The progress did not stop with completion of the new airport, twin sports stadiums or Kemper Arena. Construction began to unfold on a wave of soon-to-be iconic business addresses like City Center Square and 2435 Grand Boulevard, which continue to stand strong in the commercial real estate space. While the physical transformation was taking place, change of another sort began to set in, one that might have started with the best of intentions. It came in 1977, with the original filing of a federal lawsuit alleging institutional discrimination as the culprit behind a rapidly crumbling Kansas City School District. The case would take on national repercussions as it wound its way through the legal system over the following 25 years. That same year produced the first Plaza Flood, when Brush Creek came roaring out of its banks, killed 25 people, and inflicted $100 million in damage—more than half a billion of today’s dollars. And on a social scale, Kansas City was transforming from a football town into a hotbed of baseball fandom as the Royals rose to prominence in the American League, challenging the supremacy of the New York Yankees. It was the heyday of professional sports in this region, as we also became home to NBA (Kings) and NHL (Scouts) franchises, thrusting us into the profile of a comparative handful of four-sport towns. Much of the asphalt loop that encircles us, Interstate 435, came online, providing the spark for a development explosion—retail, office, and residential—that continues to reverberate today. And our cultural embrace of entrepreneurship inspires three Arthur Andersen executives to strike out on their own with a health-care informatics enterprise they could come to call Cerner Corp.—destined to become both the region’s biggest private-sector employer over the next three decades, then a fading memory just a few years later.

April: The 1980s. KC’s skyline continued to be redrawn, with a trio of office towers that, 40 years later, still define the view of the city from afar and retain their titles as the tallest skyscrapers in this region: One Kansas City Place, Town Pavilion and what is now the Sheraton Kansas City Hotel at Crown Center. On the sports front, years of would-a could-a yielded to championship baseball as the Royals claimed the pennant in 1980 and the World Series five years later. It was a time of civic pride and, at the start of the decade, civic horror with the collapse of the skywalks at what was then the Hyatt Regency Hotel, a stunning engineering/construction failure that claimed 119 lives and eventually others including one of Ingram’s own.

May: The 1990s. Change was in the air in a lot of ways: Union Station would rise from the grave to become a civic anchor, thanks to a one-of-a-kind collaboration by taxpayers across the state line. The city elected its first black mayor early in the decade and its first woman to hold that office as the ‘90s drew to a close. In the meantime, we planted the seeds to become a national center of excellence for soccer—the fruit from those seeds will be fully harvested in 2026—and we saw the importance of investing back into the central city the development of 18th and Vine, the American Jazz Museum and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. And as the decade was drawing to a close, a major change was building as a failing academic medical center was reborn as a stand-alone public health authority, positioning The University of Kansas Hospital for monstrous growth as a health-care provider and center for medical research.

July: The Aughts: From 2000 to 2009, Kansas City positioned itself as a community that would not let its Downtown go quietly into that good night. It began making commitments to restoring residential options in the central business district, it struck redevelopment gold with H&R Block’s commitment to build a new headquarters Downtown, and it transformed nightlife in these parts by razing block after block of blighted property to create the Power & Light District retail and entertainment zone. It topped things off by—partially—correcting a misjudgment 30 years prior, unveiling what was first the Sprint Center and now the T-Mobile Center. Major lifestyle centers spring up with Village West in Wyandotte County and Zona Rosa in the Northland, while the eastern side of the area sees a rebirth of commercial concentration along I-70 near I-435. The decade wrapped up in the throes of an economic downturn unseen in depth since the Great Depression and earning also the status as the Great Recession. Construction and design companies, long a staple of the economic scene here, pull back and regroup for better days ahead. They didn’t have to wait long.

October: 2010-2019: As the U.S. economy shifts into a mode that favors renting over attainment of the American Dream—home ownership—the Kansas City region’s construction sector embarks on a multifamily building spree unprecedented in its history. From Downtown to the Village West, from inner-ring suburban commercial districts to the suburban fringe, tens of thousands of apartments go up—a huge number of them falling into the luxury living class. And in true “if you build it, they will come” style, a series of enormous logistics facilities built on spec basis—then on consignment—propels Kansas City into national discussions about where major companies should establish shipping and distribution centers. West Coast names like Google and Amazon emerge as major pillars of the regional economy, following wave after wave of mega-warehouse construction.

November: The Roaring Twenties: A decade that began with terror on a global scale—we know it now as COVID-19—has evolved slowly into business as usual. And in Kansas City, that business is growth. While the commercial real estate markets continue to suffer the effects of diminished office and traditional retail demands, the region continues to add—massively—to its logistics footprint. But it is also a time of change as entrepreneurial success stories Cerner Corp., Sprint and Yellow lose their status as anchors of the regional economy.