HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Kansas City Region Poised for Progress

(Front row l-r) Joe Sweeney, Ingram’s; Mike Fenske, Burns & McDonnell; Don Greenwell, Builders’ Association; Jason Wiens, Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation; Ronnie Burt, VisitKC; Antonio Soave, Kansas Department of Commerce; Mayor Mike Boehm, City of Lenexa. (Second row l-r) David Yeamans, Burns & McDonnell; Nick Jordan, Kansas Department of Commerce; John Murphy, Shook Hardy & Bacon; Pete Fullerton, Kansas City Aviation Department; Mike Lally, Olsson Associates; John Novak, JE Dunn Construction; Kelvin Simmons, Dentons. (Back row l-r) Tim Cowden, Kansas City Area Development Council; Beth Johnson, Overland Park Chamber/EDC; Steve Kelly, Lawrence Chamber of Commerce; Chris Shove, 27 Committee; Greg Kindle, Wyandotte Economic Development Corp.; David Fenley, Husch Blackwell; Charles Renner, Husch Blackwell; Blake Schreck, Lenexa EDC; Greg Martinette, Southwest Johnson County EDC; Mike Hagedorn, UMB Bank.

Work-force considerations, said Mike Fenske, can’t be effectively addressed if the region fails to account for the transportation needs of workers. Nick Jordan of Kansas Department of Commerce looks on with interest.

After Mike Fenske’s opening comments to greet participants, Antonio Soave cut to the chase, asking each which issues could be identified as the most immediate threats, or greatest potential opportunities, facing a region united in purpose, but divided by a state line.

“From our perspective,” Soave said, “it’s more coordination across state line. I think there’s been a mischaracterization in the past as to how we viewed each other from each side. But those of us who live in metropolitan Kansas City know that this functions very much as one metropolitan area. We not only like each other, but depend on each other for broader economic development.”

Antonio Soave began the discussion by noting the wide range of collaborations that exist between Kansas and Missouri.

Nick Jordan, former secretary of revenue in Kansas, is now working with Soave’s department, leading the Governor’s Economic Advisory Council. He said he had recently spent several days with the state’s education com-missioner, exploring ways to prepare students and give them the skills they need to succeed in business. “It’s going to take a great business and education partnership,” Jordan said, “and only business will know what the skills need to be today and what they need to be 5-10 years from now. It’s not about just getting employees, but people with the right skills.”

Greg Kindle, president of the Wyandotte Economic Development Council, immediately cited the need to better match existing human capital with employment opportunities, irrespective of where the job is sited. “I’d be very supportive of growth in Johnson County or Lee’s Summit if I knew Wyandotte County residents could get to those locations to work. How do we connect those projects and assets and raise overall household income?”

“It’s imperative,” said Don Greenwell, “that employers in the Kansas City area generate the kind of demand for modern work-force skills that will help drive the regional economy forward.”

Don Greenwell, president of The Builders Association, suggested flipping over to the hiring side of the equation: “We need to have demand from business for skilled, professional employees.”

Former Missouri Department of Economic Development Director Kelvin Simmons, a principal with the Dentons law firm, said that with efforts to encourage growth on both sides of the state line, “the challenge is ensuring that all neighborhoods, communities and people have opportunity to share” in that growth.

As director of commercial properties for key elements of the region’s transportation assets in his duties with the Kansas City Aviation Department, Pete Fullerton pointed to the “critical infrastructure that needs to be invested in and reinvested in,” on both sides of the state line. With discussion touching only briefly on the evolving debate over the future of Kansas City International Airport, Dave Yeamans noted that in his role overseeing the aviation and federal group for Burns & McDonnell, opportunity is knocking. “With the airlines being very profitable these days,” he said, “they’re starting to spend money, and we’re working all over the U.S. in airports every day.”One possible translation of that: Other cities are upgrading. Kansas City isn’t—yet.

Mike Boehm added the perspective of an elected official as mayor of Lenexa, saying the biggest issues on each side of the state line have to do with “budgets, funding, discourse and partisanship.” All can have an impact on regional higher education and workforce dev-elopment, he said, and citing the need for local governments to pick up a share of infrastructure maintenance and operation, “we can’t do it with tax lids and things of that nature being imposed by state government.”

Life sciences, design and logistics are all areas where this region has a national, even international reputation, said John Murphy.

Steve Kelly, formerly with the Kansas Department of Commerce but now vice president for economic development at the Lawrence Chamber of Commerce, said discussions about work-force training too often miss a key element. “We focus a lot on K-12 and college, and pay too little attention to the technical side,” he said, calling it an area of the economy that is suffering from lack of both manpower and skill sets. Those non-degreed skills “can lift folks out of bad situations and allow them to be successful for a long-term period.”

His economic development counter-part from Lenexa, Blake Schreck, sug-gested that “from a state standpoint, the instability in tax policy and whiplash back and forth from both states to attack the tax mix and its response is creating the perception that we’re unstable and volatile” as a region. But an even bigger problem looms, he said, and must be addressed: “The sustainability of the rural parts of our state, how we go forward in western and southeast Kansas.” Failure in those regions, will ultimately drag down nearby metro areas, he said.

Mike Lally, vice president with Olsson Associates, an engineering firm, told the story of a meeting the previous evening with an economic development professional, and their discussion touched not on site selec-tion or incentives, but about work-force issues—for a full 90 minutes. And with respect to infrastructure, he noted, “things age before our eyes. It’s amazing how things get old. We build something, and before you know it a school is 20 years old, a roadway 40 years old, and we haven’t done anything for them. We have to heighten our awareness, because it’s the grease that makes the private sector run well when infrastructure is in place.”

Jason Wiens cited new figures that show the Kansas City area is improving its standing as a center for entrepreneurship.

Greg Martinette, president of the Southwest Johnson County Economic Development Corp., said many of the issues around the table can be traced back to leadership, and leadership must exert its influence. “These are important, and all of them feed off each other.” Perhaps more troubling is the current collective work ethic; the best work-force training in the world, he said, won’t amount to anything if people don’t want to work.

For John Novak, vice president at JE Dunn Construction, pro-gress will come when business and the public school systems improve their relationship. “Getting K-12 leadership to not be resistant to change is critical—it’s both a chal-lenge and opportunity for the two of them.”

Raising an alarm in a whole new sector, Beth Johnson addressed the dramatic changes in retail settings, something she sees daily as senior vice president for the Overland Park Chamber of Commerce. Nearly one U.S. job in 10 is in some type of retail venue, and the precipitous decline in traditional sales, brought to you by e-commerce, is changing the very face of cities. “It is potentially an opportun-ity going forward,” she said; “but we continue to see changes in how buying works on line.” Close to home, her own 26-year-old doesn’t buy anything at a store if it’s available on-line, with door-step delivery. Retail bank-ruptcies, she said, “will leave us with some real estate challenges, and we have to figure that out for the next generation.”

As it happened, the Kauffman Foun-dation, where Jason Wiens works in the study of entrepreneurship, had released its annual Start-Up Index that very morning. “Kansas City moved up to No. 15 among the 40 largest metro areas in the country,” he said, and increased growth and new business creation presented opportunities to capitalize on both.

UMB Bank’s CEO, Mike Hagedorn, delivered a concise summary of three key challenges facing the area: “Mini-mum-wage jobs; we need to touch all the socioeconomic areas of our city. Second, infrastructure—the airport needs to be done” and admittedly self-serving, in his capacity as chairman of the streetcar authority, he added, “we need the streetcar extension. It makes Kansas City cool, and the cool factor is helping our region attract and retain talent, because they want access to public transport. Last, capital formation; there’s not enough of it in our com-munity. It’s not just about the banks. Getting venture-capital money from the coasts is a high priority for our community.”

Two Husch Blackwell development-law experts, Charles Renner and Dave Fenley, circled back to education and the air-port. “It gets back to the strength of schools,” Renner said. Fenley qu-oted former Kansas City Mayor Emanuel Cleaver, who frequently referred to Downtown as the metro area’s living room. As with improvements made there, the airport presents an opportunity, he said. “It’s really there for the taking.”

One of three co-chairs for Kansas City Rising, a business-oriented group pushing for work-force improvement growth opportunities, Shook Hardy & Bacon’s John Murphy pointed to three opportunities where “we have a national brand, probably even an international brand: Our life sciences nexus, the global design opportunities we have. The fact that we are the geographic epicenter for logistics and transportation.”

Assessing the talent at the table, CEO Tim Cowden of the Kansas City Area Development Council recognized the abilities to identify key concerns, but pointed out to one that is more intangible. “I think the challenge for this region is leadership,” he said. “Look around this table, and outside of Beth,” he said with a diplomatic dash of chivalry directed Beth John-son’s way, “we’re all pretty old, right?” Kansas City faces not just a series of unique challenges and opportunities, but questions about who will succeed the current generation of leaders to take the handoff and address these multiple challenges, some of which can’t be resolved even within a decade

or more. “That’s the most critical element facing this region going forward—leadership,” Tim Cowden de-clared.

One way this region can begin addressing concerns related to talent, said Chris Shove, with a group called the 27 Committee, affiliated with the Army presence at Fort Leavenworth, is by recognizing what’s at stake with the military presence in the region, particularly with soldiers and officers mustering out of active duty.

“Fort Leavenworth has a $2.3 bil-lion impact on the Kansas City area,” Shove said, and “a lot of soldiers get out every year and decide to live in this area. The challenge is to transition them into the work force.” That’s key, history and Army programming has shown, because some of those exiting with the Army’s help are hired into jobs that average $90,000 per year, a clear reflection on the skill sets they bring to employers.

What this region’s business and civic leaders need to understand, said Ronnie Burt, CEO of VisitKC, is that no matter how clearly they can perceive challenges, if the pace of solutions doesn’t match what’s being addressed in other cities, this one will fall further behind. “When you don’t move quickly, you miss a significant opportunity and have to play catch-up” he said. “Every-one has a different suggestion on how we get caught up, and it stalls things. We have to simplify issues, create alignment and move at a fast pace.”

Taking an informal census of what he’d heard around the table, Antonio Soave produced a checklist that would leave many a public official in awe of the tasks ahead: Achieving consensus on infrastructure improvements to elevating the work force, aligning state and local budgets with the needs of education, bringing regional tax policies into synch, safeguarding rural interests and promoting development in those areas, new business development, capital formation and promoting inno-vation.

Clearly, this region has a full plate on its table, should its leaders choose to dig in.

For Greg Kindle, a major concern is how to get workers with lower skill

levels to the locations that have more of the jobs they can perform.

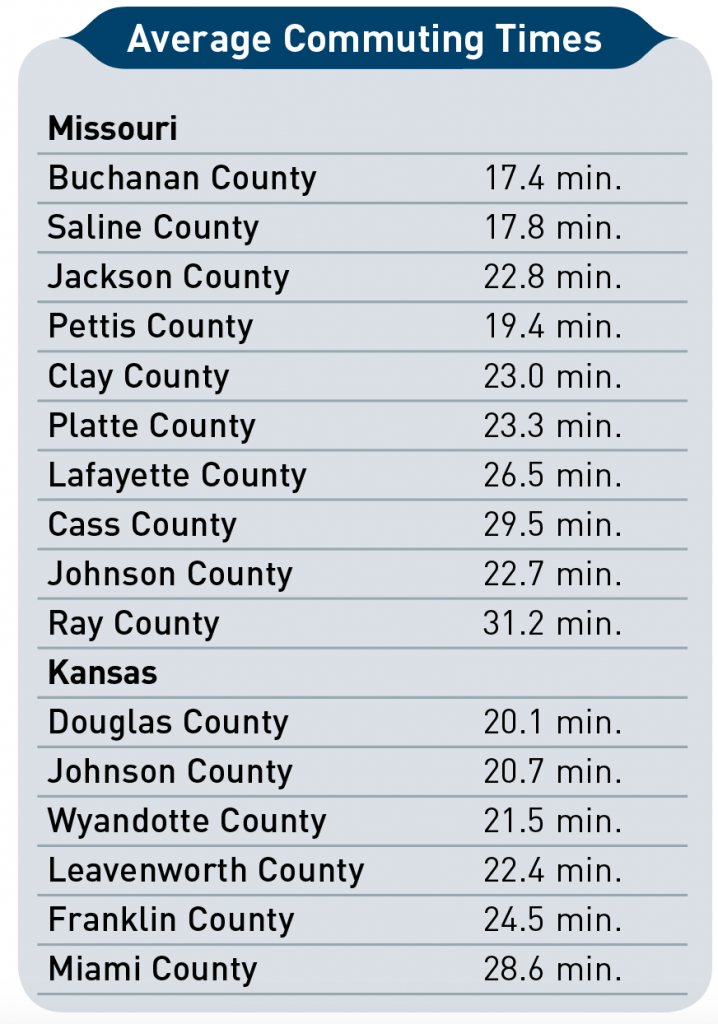

Co-chair Mike Fenske addressed the relationship between the work force in this region and its urban/suburban composition, raising the question of how best to provide a competitive urban environment for a working class that spends, on average, 30 percent

of its income on transportation alone. (For the doubters, start by calculating car payment, insurance, fuel, main-tenance and various taxes, including property and gasoline, and applying that against the region’s median pretax household income of roughly $60,000 in 2015).

Addressing the regional multiplicity of lifestyles, Mike Boehm noted that during decades of Downtown decay, the thriving suburbs contributed greatly to the quality of life in the region. With more than $7 billion invested to bring Downtown back to life over the past

15 years, there is a certain seamless-ness that allows for diverse, high-quality experiences. “We have options for Downtown, the River Market, the Crossroads as well as the suburbs,” Boehm said. “I’m reluctant to toot our own horn, but when people come here, they don’t leave.”

A couple of factors impinge on the success story that is Kansas City’s, he pointed out: One is the nearly endless barrage of media attention rooted in a crime-as-news mentality—police-report journalism being a low-cost alter-native to paying reporters to do more substantial work. The other is a certain level of NIMBYism exhibited by some of those who have reaped disproportionate rewards from what the region has to offer. In some communities, he said, “now, the $400,000 homes aren’t good enough any more. We’ve got to educate some people that there has to be place for everybody; not everyone can live in a $600,000 house.”

Tim Cowden offered a contemporary example of how undersold this market truly is. A group of executives doing site-selection work was here recently, having winnowed the potential markets for a certain business from 500 down to three—Kansas City being one of them. “Over the course of 26 hours, to see how their perception was changed, how really good they felt about the opportunities here—the point I’m making is that on a spreadsheet, our region looks like a lot of places. But when we get them here, they don’t want to leave.”

That is an example of how the region must seize opportunities, he said. “We have a good shot at this company, but have to take this momentum; it’s not time for complacency, but time to double down and leverage the opportunities we have in this region.”

Perhaps the biggest advantage for the region to do so, he said, was the recognition from corporate representa-tives that the region has a crack team of development authorities, in both public and private sector and on both sides of the state line, who work effectively to meet the needs of expansion-oriented executives.

Rather than being a line of division, said Greg Kindle, the state line had created opportunities for competing public interests to hone their market-ing messages and their incentives in a truly competitive environment, pro-ducing attractive options for companies seeking to locate here. If, however, there is a missing piece to work-force fluidity, it would involve transportation, he said.

“I love the intermodal project” in Gardner, some 15 miles south of the Wyandotte County line. “It’s one of the best industrial parks in the world, but I can’t get people from our county on a bus to Edgerton for $10-$12 an hour and still raise their household incomes,” he said. “We have to find solutions that solve basic issues.”

If there were ever a time to sell Kansas City, that time is now, said Blake Schreck. “In my 30-plus years of doing this, Kansas City is at its highest point now from an awareness standpoint,” he said. “There is a hip quotient, and we have that now. The past three years, I’ve never seen so much publicity about our hipness or our coolness. Maybe having the Royals in the Series every year helps, too, but we’ve been doing some good things along the way.”

Too many people in this region, said John Murphy, “don’t recognize what you have from a global standpoint in Kansas City. There is a lot of sizzle right now.”

But are we prepared, Mike Fenske asked, to match that sizzle with the kind of business environment that innovators and disruptors are looking for?

“If the region is to succeed economically,” said Kelvin Simmons, “it must take steps to ensure that the benefits of that growth reach into every neighborhood and community.”

“I would answer with a resounding ‘yes’ that we are,” said Kelvin Simmons. The first-in-the nation opportunities with Google Fiber had broken a lot of ground with young entrepreneurs and created a buzz among them nationwide. “We have to be sure that we get that entrepreneurial spirit here, but from a government standpoint, that we don’t over-regulate.” To an extent, the region has succeeded, he said, “and it’s not my father’s Kansas City. But for my daughter, who I would hope to retain and keep here, I want it to be a different Kansas City in the coming years, and not the same as mine.”

Area municipalities, Boehm said, had been guilty of over-reach by licensing everything from Pac-Man video games in the 1980s to cell towers in the 1990s, most recently, imposing res-trictions on shared-economy ventures like Uber and Lyft. “Disruptors are scary,” he said, “but we need to do a better job of knowing what’s coming before it gets here, then planning and reacting appropriately.”

That’s absolutely vital, said Steve Kelly, because companies from the outside don’t see the regional market as a collection of municipalities; they see it as a market. When local regulations create conflict and confusion, it has the effect of discouraging interest in expanding here. “They have to have some clear understanding of what the ground rules are so they can understand on a broader basis that this is how it operates in the region, and it is not just a Lee’s Summit, Lawrence, Lenexa or Olathe that will complicate their lives with ordinances that are inconsistent or that create barriers in one market or another.”

“College diplomas of yesteryear don’t mean the same thing today that they once did,” said Nick Jordan

Nick Jordan noted the importance of retaining existing talent, as well as attracting it. “Only about 17 percent of our university grads are staying in the area,” he said. “That’s not a selling point to companies, we have to convince our young people that we’re hip and they can do well and don’t have to go to the coasts to make a good living.”

That, he said, goes beyond hammer-ing into them the message that a good life comes only with a college degree. “The 4-, 6- or 8-year diploma is not necessarily what it used to be,” Jordan said. “Kids can get a 2-year certification at a technical school and still come out pretty good, particularly in computer science.”

But there’s room to improve the kind of collegiate instruction students receive, said Beth Johnson. She noted that many young engineering hopefuls get a taste of what that work entails through advanced programs in high school, only to find in college that hands-on work is two to three years’ distant, because of prerequisites needed. Changes at the KU-Edwards campus to get them into actual project work right away, she said, “we need those types of changes where students feel more engaged.”

Steve Kelly hit on a vital point when he said that Kansas City would miss out on growth opportunities if it tried to be something it’s not—as in another

The decay of critical infrastructure, said Mike Lally, often occurs unnoticed because it takes years to manifest itself.

Silicon Valley—while ignoring what it could be: The animal-health corollary to Silicon Valley. “We need to take advantage of our assets just as folks in the valley have with theirs. Rather than aspire to that, we should support our industries here—it’s a real jewel we need to grow.”

As a region, we have the potential to do just that, said Blake Schreck, because of a solid foundation of collaboration that has been decades in the making. “We have shown that growth doesn’t have to be mutually exclusive,” he said. “We have had good solid growth in the urban core. We had it in the suburbs, too. We’ve become diversified enough to become a world-class city. We just need to focus on the stuff we do well.”

The Greater Kansas City Economic Development Report is published by Ingram’s Magazine and is part of a series of ED Assemblies and Reports published throughout the states of Missouri and Kansas.