HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Congressional bills that run past 1,000 pages, and the legislative processes that produce them—as with the Affordable Care Act and the Dodd-Frank financial reforms—failed to generate much outrage with the voting public in recent years, despite ample evidence to demonstrate that neither had achieved its stated goals.

Perhaps it was only a matter of timebefore we’d see four-figure administrative actions. The most recent of those is the Clean Power Plan, rolled out in early August at an impressive 1,560 pages, with thousands of pages to follow. Combined with thousands of pages of additional guidance still to come, it will do for America’s energy sector, critics say, precisely what ACA did for health care expenditures and Dodd-Frank did for compliance costs at community banks.

Only this time, anyone whose electricity comes from burning coal will be able to see the effects on the monthly utility bill.

“It will be, by far, the most expensive compliance policy the EPA has ever undertaken,” cautions Andrew Ferris, director of electric supply planning for the Kansas City Board of Public Utilities. At $311.5 million in 2014 revenues, the Wyandotte County-based municipal utility is but a fraction of the size of investor-owned utilities like Great Plains Energy, parent of Kansas City Power & Light, or Westar Energy in Topeka.

But the BPU will more acutely feel the effects of new federal restrictions because it lacks the economies of scale enjoyed by the larger utilities. The effect would be multiplied within this region because the utility not only produces power for 63,000 customers in the county, but hundreds of thousands more who rely on it to power municipal water systems in the region, including Johnson County’s massive Water One.

At this point, the BPU has no solid estimates on what the costs of CPP compliance will be, Ferris says. An hour to the west, Westar’s John Bridson has a more forceful opinion about what the CPP will impose on consumers and businesses: “I think the impact to the people of Kansas is going to be big, and that concerns us because we’re worried about those families’ ability to live the kind of lives they want,” says Westar’s senior vice president for generation and marketing. “This isn’t going to help that out any.” Westar has run some early scenarios, he said, “and it looks to us like the price tag for Kansans will be in the billions of dollars.”

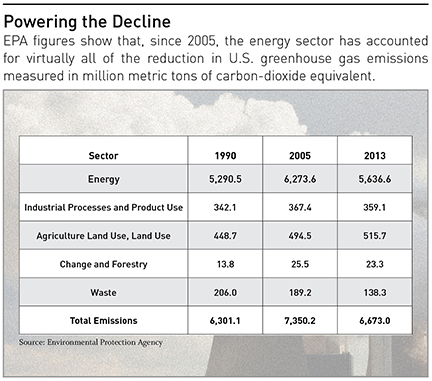

Aimed at reducing carbon-dioxide emissions—basically by making it nearly impossible to use coal as an energy source the way it is today, the plan would tip the balance of power generation toward renewable sources like wind and solar. From a national perspective, that would levy a disproportionately high toll on consumers—and businesses—in the Kansas City region; EPA figures cited by the Congressional Research Service, rank Missouri seventh nationally, and Kansas eighth, in production of CO2 emissions.

Many of the older, less efficient coal-fired units already have been closed across the nation, or modified to burn natural gas. But the Clean Power Plan would dictate far more strident rules in this region. By 2030, it calls for CO2 generated by utilities to be cut nearly in half in Kansas—44.2 percent—while Missouri would see a 36.7 percent reduction.

There is, utility executives say, no practical way to get where the EPA wants to go without a) significant increases in rates; b) significant risk of supply disruption, to the point of major blackouts; or c) significant aspects of both.

“It’s complicated. It is going to cause rates to go up more than they would be otherwise,” said Warren Wood, vice president of external communications for Ameren Missouri, the state’s largest utility.

The plan released by the EPA in August was not without its ironies, Wood said. “You talk to co-ops, KCP&L and others who have spend literally billions building renewable energy resources, and some of those resources that we’ve built in expectation of compliance with CPP, the way they drafted it, wouldn’t be useful for compliance now,” he said.

That’s one potential hidden cost of the plan, but other costs are much easier to see.

Right now, Wood said, using a conservative estimate using EPA’s own number of $37 per ton of cost for carbon reduction, “do the math, it’s a little over $6 billion in state electricity costs by 2030. We think there are a number of scenarios where the number is billions higher than that.”

That’s why he expects Missouri will join more than 20 other states challenging the Clean Power Plan in federal court. “We think there is a real challenge to due process” in the way the plan was formulated, he said. “We think they’ve stepped well beyond the bounds of the Clean Air Act.”

As Wood and others have noted, utilities have long been preparing to spend billions on new infrastructure in any case—the systems put in place in the 1960s and 1970s to meet an explosion of demand growth are reaching the ends of their useful lives. But there’s a considerable difference in cost to consumers if a utility replaces an old coal-fired plant with a newer, more efficient one, as opposed to building a new facility that requires an altogether different fuel source.

The Underlying Economics

At the heart of the dispute over whether CPP is good policy or bad are multiple disagreements over a number of other issues:

— Whether the U.S. can sharply reduce coal usage without wrecking the nation’s economic fundamentals of the nation.

— Whether the plan itself will do any good to reduce CO2 emissions on a global scale, considering increased coal-fired demand in emerging economies worldwide.

— Whether renewable energy sour-ces can retain their value to consumers without the subsidies that have supported that sector for 40 years.

— Whether the nation is prepared to do what’s necessary to replace infrastructure from the Coal Era with transmission lines and facilities that can support renewable generation.

Start with the competitive advantages we enjoy as a nation. For two generations, the rationale for sending manufacturing jobs overseas was that lower labor costs would easily offset the added costs of shipping product back to the U.S., and in many cases, the higher costs for energy in those countries. With labor costs rising worldwide as India and China see expansive growth in their middle classes, one major benefit of outsourcing production to those nations is vanishing, putting America in a more competitive position to retain that kind of work.

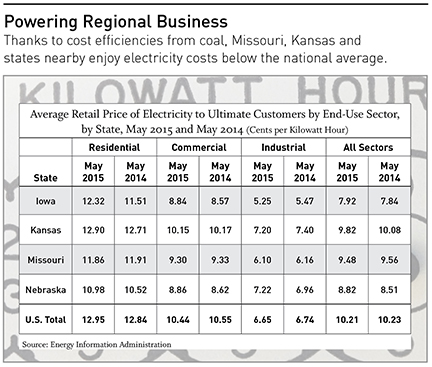

Now, that advantage could be fading as the price of a kilowatt hour of electricity is likely to surge from the national average 12 cents to—well, even the experts aren’t sure how high it might go under CPP. The calculus changes for manufacturers who have long looked at energy two and three times the U.S. average in places like Germany, Spain, Australia and Japan.

Critics of CPP find no shortage of economic assumptions that they consider suspect.

“Numbers are funny things,” said Ferris. “They can be whatever you want them to be. I think their thought (at EPA) is that people will consume a lot less energy. As their bill goes up, they’ll shut off lights, buy energy-efficient appliances. But I do think their costs are extremely conservative. We’re taking everything with grain of salt in terms of how partisan any of these studies are.”

While the EPA has used a figure of $3 billion to assess the plan’s economic impact from higher costs, “It’s looking likely to be more like $30 billion annually, well more than what EPA is quoting,” Ferris said. “The coal industry thinks it may well be more than $40 billlion. Is that accurate? It’s hard to say.”

But what’s clear, he said, is that the EPA’s estimate of the current compliance cost for MATS—Mercury and Air Toxins Standards—is roughly $10 billion, and that policy addresses actual contaminants like sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxide. “This is three times more expensive for a much smaller incremental benefit to people who live in the U.S.,” Ferris said.

It’s particularly ironic that the plan comes after a decade-long drop in so-called carbon pollution nationwide. “We are one of the few industrial countries that have done that,” Ferris said. “Look now the BRICs, the developing countries, producing well over 60 percent of the carbon globally. A big piece of the smog you see over Los Angeles is movement from China across the globe to that area. What we do in the U.S. will have a very minimal impact globally.”

The CPP authors maintain that higher energy prices will more than be offset by saving on health-care costs for treating illnesses related to burning coal. Many a thigh in utility executive suites has been bruised with the knee-slapping that claim generates.

“It’s hard for us as utility people to follow how they came up with the benefits” laid out in the plan,” said Westar’s Bridson. “They throw a lot in there related to individuals’ health. If we had to back it up with facts, it’s not something we can verify. What we can start to understand and eventually verify is what the costs are going to be with that impact on Kansans.”

Take for example, replacing coal generation with natural gas. “It’s hovering around $3 (per 1,000 cubic feet), but what we know is that, historically, the price is very volatile,” he said. “We could see stabilizations, but can’t expect that to hold. No one can predict that, vs. coal, which you have sitting in the ground, ready to be dug up. That’s very un-volatile.”

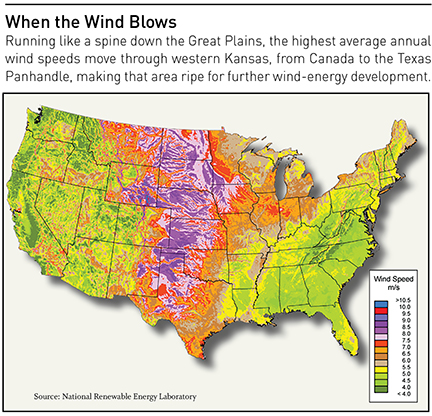

The obvious criticism of non-carbon renewable like wind and solar power has long been grounded in the reality that, on many days, the wind doesn’t reach the roughly 10 mph speed necessary to turn a turbine blade, or, as a solar-panel salesman in Seattle can attest, the sun isn’t always shining.

The argument against renewable-energy infatuation is more than that. The much-publicized shrinkage in the gap between solar and traditional energy can still be attributed to the subsidies that support the solar sector. But even with wind blowing and sun shining, he said, this nation hasn’t come to grips with how power will be transported from areas where renewable energy is being gathered, to cities where it would be used.

“It doesn’t seem to be talked about much, but transmission is the big key behind the whole renewable space,” Ferris said. “You have to be able to move that energy to the source that requires it, and we’ve seen over the past couple of years those large transmission projects have not come to fruition.” Case in point, he said, was the proposed Grain Belt express, which would have delivered wind power from the Dodge City area in western Kansas to a substation near Chicago, 750 miles away. It ran into significant opposition from landowners, and is still not approved.

For the Kansas City region, in particular, there’s a positive aspect to CPP implementation that few other markets will experience: The huge volume of engineering services in this region means that expertise in power delivery design and construction likely will lead to additional work for firms like Burns & McDonnell and Black & Veatch, as well as smaller firms with a sharper focus on energy delivery.

“The difference between his rule and previous rules that have come out in regard to the environment is that most of the others have been an incremental change in strategy, not necessarily a holistic review of your business model.” Said Block Andrews, strategic environmental solutions director for Burns & McDonnell. “That’s what this new plan has generally done.”

With previous regulations, he said, “when they came along, you probably had a solution to keep your coal unit running that was economically feasible. When you look at this one, the options are a lot fewer. You may be able to co-fire with gas and coal to help meet the targets, but putting on back-end controls, the technology is out there, but it’s so cost-prohibitive, you’re not going to do that in this market. The decisions that utilities are having to make, and evaluating now, are much bigger than in the past.”

What regional utilities have going for them—indeed those nationwide who for decades have drawn on the Kansas City region’s engineering assets—is deep experience in all facets of power production, not just coal-fired. Like Burns & McDonnell, Black & Veatch has extensive expertise in wind, solar, biomass/gas and hydro-electric generating design.

Utilities, Andrews said, “know they’re going to have to reduce their greenhouse gas footprint, but there are a lot of ways to do that. So we try to make sure our skill set is consistent with the type of work those utilities would need.

Ed Walsh, Executive Vice President and Executive Director of Global Services Projects in Black & Veatch’s Energy business, said that even though the CPP was just released, “our clients are talking to us about what we think the possibilities might be and how the EPA directives might impact state plans, and the effect on any stranded assets on their individual systems or projects being developed. A lot of our clients and owners are concerned about what their customers’ reactions will be—will this allow rates to be stable, increase or decrease.”

One thing that that should keep business flowing at Black & Veatch, he said, is the diversity of business lines within the power sector. “We have a great deal of renewable power delivery experience as well as gas fired and coal experience, so when we look at the change in the asset mix that will likely come, we’re still very bullish on the U.S. market and business opportunities,” Walsh said.

And domestically, “we predict that renewables will go from today’s level of 13 percent to 28 percent by 2030,” he added. “But even at 28 percent, there’s still a need for lots of gas-fired generation, and believe it or not, still a fair amount of coal-fired.”

Then, too, he noted, India, China and other countries with emerging economies will continue to build coal-fired plants, albeit more modern versions with improved emission controls.

“I tell young professionals, my biggest point of envy is I wish I was their age: with the new technology, the fact that energy is on a global scale now, it’s an exciting time to be in this business,” Walsh said.

For producers, what’s most discouraging may be that the national conversation about energy use is focused on the wrong end—at the smokestack, instead of at the first link in the power chain.

“Rather than put billions into research to come up with innovative ways to deal with CO2, they’re regulating and causing us to start moving away from coal,” said Don Gray, Ferris’ boss at the BPU. “That’s going to increase costs and decrease reliability. We’re almost certain of that, because just inherently, all this intermittent energy is harder to manage.”

What’s needed, he said, is a breakthrough to scrub the CO2 before it goes through the smoke stack. “But they don’t talk about that,” Gray said. “The way we seem to solve problems is just regulate them, throw them in our lap, and say ‘OK, boys, you deal with it.”

The bottom line, though, is that electricity costs in Missouri, Kansas and other parts of the country are going in only one direction: Up.

Without coal, “whatever direction we go for generation, it’s going to cost more and more for that energy. It’s just automatic,” Gray said. “It’s going to cost more—for consumers and for businesses.”

According to the National Federation of Independent Business, energy costs are one of the top three business expenses for more than a third of all small businesses, and that small businesses, on average, pay up to 52 percent more for their energy than do large power users.

So it makes sense to take control of things from your side of the utility bill. Some tips offered by utility companies:

• Start with an energy audit. These affordable assessments of your use—and waste—can pay for themselves almost immediately with a few minor moves to cut use and conserve.

• Lighting is low-hanging fruit. Take, for example, 32-watt T-8 fluorescent tubes, some of the most common light-ing at U.S. businesses, along with 400- and 175-watt incandescent bulbs. If you upgrade all three types, you may run into a substantial up-front cost, but even with that project financing, some small businesses have seen utility and maintenance savings that cover the financing costs and generate net positive cash flow of $1,000 to $3,000 a month.

• Commercial LED lighting, combined with solar panels or other energy-efficient devices, are excellent choices for facilities that need to have the lights on all day, every day. That approach has cut energy costs at health-care facilities by 20 percent, or more than $111,000 at a 150,000-square-foot hospital.

• Area electric companies—Kansas City Power & Light, Independence Power & Light, the Kansas City Board of Public Utilities, Westar Energy and smaller producers—all have various programs to help individuals and com-mercial/industrial customers assess their use and reduce it. Think about that: What other provider encourages you to use less of its product and gives you tools to do that? Check the various Web sites for details.

• On smaller scales, companies can attack energy costs by getting rid of energy-guzzling appliances and office equipment.

• Learn about passive consumption: 75 percent of appliance energy is consumed when you’re not even using it, like that plasma TV in the lobby, office computers, coffee makers and the like. Turn them off when not in use and save.

• If your building uses an electric water heater—or more than one—set the hot water heater temperature at 120 degrees and cut heat loss with insulation blankets.

• Sealing and insulating air ducts can improve HVAC system efficiency by as much as 20 percent, and you’ll realize greater savings by sealing doorways and windows, too. Programs like KCP&L’s Demand Response Incentive offer incentives for strategic reducing of energy use on peak days. A minimum reduction of 25 kilowatts qualifies companies for the utility’s load-management program and earn discounts on summer energy bills.

• Programmable thermostats especially in commercial buildings that don’t require uniform levels of heating and cooling—can cut those costs by up to 20 percent. Lowering a thermostat by 7-10 degrees for eight hours a day can cut 10 percent from your bill.

• Re-examine solar. Costs for solar systems have been plunging, and are beginning to approach traditional power sources, albeit with a federal subsidy still kicking in. But if it’s been a few years since you priced solar, and decided it wasn’t worth it then, it might be a good idea to revisit the topic.

• Tax credits for various energy-efficiency devices remain in place, and among those that are locked in through the end of 2016, there are solar credits of up to 30 percent of costs—with no maximum credit. The same goes for fuel cells, with a cap of $1,500 per 0.5 kilowatt of capacity. And that 30 percent goes for small wind turbines placed in service after Dec. 31, 2008. For geothermal systems, micoturbines and Combined Heat and Power properties, the credit is equal to 10 percent of expenditures, with no maximum.

• At the state level, Missouri offers an Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Tax Credit, while Kansas has offers its own Alternative-Fuel Tax Credit and a Renewable Energy Property Tax Exemption in various amounts, among other programs.