HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

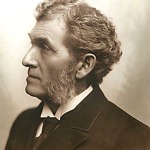

He just might be the perfect face of philanthropy in Kansas City—after all, Robert A. Long was born in December 1850, just six months after Kansas City came to be. His lumber concerns helped build a fledgling city, and by the time he died in 1934, he had built a legacy of giving that includes not just his former home, Corinthian Hall (now the Kansas City Museum), or land that became the Longview Community College campus, but a standard of philanthropy that continues to define the city today.

He just might be the perfect face of philanthropy in Kansas City—after all, Robert A. Long was born in December 1850, just six months after Kansas City came to be. His lumber concerns helped build a fledgling city, and by the time he died in 1934, he had built a legacy of giving that includes not just his former home, Corinthian Hall (now the Kansas City Museum), or land that became the Longview Community College campus, but a standard of philanthropy that continues to define the city today.

“To me there are some things in this world far dearer than the accumulation of money. … Men become great and good and mighty not because of the amount they make, but because they utilize the money they accumulate… The world knows Kansas City is a great commercial city. It is my desire that the most essential element… the humanitarian side… be kept fresh in the minds of the people.” — Robert A. Long

Of course, others came before him, bearing gifts worth sums unfathomable to most people in that era, and many in this one. Thomas Swope, whose spectacular gift of 1,334 acres of land touched off a citywide celebration in 1896 and created a jewel of municipal parks nationwide. Or William Rockhill Nelson, the newspaper publisher whose philanthropy is memorialized on the art museum that bears his name. Or August Meyer, the mining magnate whose vision of a gift to successive generations benefits the city today with its renowned system of boulevards—including one marked with his name.

But the city rose from the riverbank and grew up with—and because of—what Long achieved in business. And the sentiments he so artfully stated about the relative merits of wealth—measured against greater needs and uses—have framed philanthropic activity and helped Kansas City earn a reputation as one of the leading cities in this nation in terms of what its people leave for future generations.

The reputation endures today, for several reasons.

“Kansas City is pretty unique in its philanthropic footprint, and for historical reasons,” says Laura McKnight, co-founder of Mulberry South, which works to strengthen the bonds between non-profits, companies and stakeholders. She was also president and CEO of the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation—now the region’s largest—for six of her 11 years there.

Part of that reason for that footprint, she says, “is that based on research around motivations for giving, people in Kansas City, when they’re asked why they give, say that the No. 1 reason is to make the community better. That’s a very different reason than other areas of the country.”

Like the founders, people today continue to give through a civic pride and civic spirit, McKnight said. “They give to make the community better. Another reason is that Kansas City’s entrepreneurs have a strong history of entrepreneurship and innovation, which we know, but a very strong history of people who built businesses made fortunes, and who made reinvesting through philanthropy a very big part of the culture in Kansas City.” A third aspect, she said, “is a real attitude of authenticity and celebration and a very human approach to philanthropy—really valuing each human being, and every gift making a difference. Whether it’s $25 or $2,500, we celebrate every gift.”

Tracing it back to its 19th-century roots, McKnight said, reveals the strong streak of independence that marked people forging new ground in a new city, building where nothing stood before. “By nature, they were very innovative, resourceful, self-made, and freedom was very important. Those values translated into this very authentic approach, very positive, self-driven,” and something that, as it grows, builds on its momentum.

These are people she says, who—if they have something to give at all—believe they have a lot. “The worthiness of the people who give a lot vs. a little is equal, and that’s the spirit that has helped Kansas City’s philanthropy survive,” she said. “Those who give $100 or $1,000 feel every bit as valued as those who give millions. That’s what keeps the culture here really strong.”

What follows is by no means a complete roster of those who have given on a grand scale, but each of them has, in his own way, helped strengthen the fabric of the philanthropic quilt that covers Kansas City. Some gave millions—in some cases, tens or hundreds of millions—some gave lesser amounts, as McKnight noted. All made a difference.

Texas, they say, is where Cattle is King. That may be true today. But 150 years ago, Missouri had three times the number of souls living in the state—and they were hungry. To meet that demand, as well as appetites of the masses Back East, cattle ruled. It’s not for nothing that Kansas City was known from its infancy as a cow town. One who made it thus was Simeon Armour (1828-1899), a Chicago lad who was one of five Armours whose name even today is synonymous with meat. Armour & Co. would grow to employ 5,000 people at its West Bottoms plant. Simeon Armour was a key promoter of a system of parks and boulevards that would define a new city. And when he died, he left an estate worth as much as $96 million in today’s dollars. His widow used a portion of that to help the Women’s Christian Association to build a home for elderly couples on what today is Hospital Hill.

Texas, they say, is where Cattle is King. That may be true today. But 150 years ago, Missouri had three times the number of souls living in the state—and they were hungry. To meet that demand, as well as appetites of the masses Back East, cattle ruled. It’s not for nothing that Kansas City was known from its infancy as a cow town. One who made it thus was Simeon Armour (1828-1899), a Chicago lad who was one of five Armours whose name even today is synonymous with meat. Armour & Co. would grow to employ 5,000 people at its West Bottoms plant. Simeon Armour was a key promoter of a system of parks and boulevards that would define a new city. And when he died, he left an estate worth as much as $96 million in today’s dollars. His widow used a portion of that to help the Women’s Christian Association to build a home for elderly couples on what today is Hospital Hill.

The name George Sheidley (1835-1896) is rarely bandied about town these days, If you’re a patron of the Kansas City school district, though, you can thank him for helping plant an early seed that led to a reputation generally more positive than it has today. He made money investing in the first cable-car company, with lines running as far as Rosedale, shipping on the river to St. Louis, and various real-estate holdings. When he died six years after a stroke, this Pennsylvania native left a fortune that would be worth nearly $24 million today. A portion of that went to KC’s Board of Education, which used the gift to buy 10,000 books for the district’s library, increasing its total by a third.

Frank Niles (b. 1858) was another Pennsylvanian who heeded the call from John Babsone Lane Soule of the newspaper in Terre Haute to “Go west, young man”—the line is usually ascribed to Horace Greely—and Niles did that, understanding that a city of successful business owners would surely need a supplier of locally rolled cigars. The Niles & Moser Cigar Co. launched in St. Joseph in 1899, moved to Kansas City later that year, and made him wealthy and helped him establish a reputation as one of the city’s leading philanthropists of the era. He and his wife, Emma Niles, donated the land and built a mansion for up to 100 orphaned

or homeless children, on the site where the Niles Home for Children stands today.

Robert A. Long (1850-1934), founder of Long-Bell Lumber Co., left marks on this community that are tangible reminders of his presences: In addition to Corinthian Hall, he built the city’s first skyscraper, his Longview Farm and mansion were masterpieces of stonemasonry and landscaping, and he was a champion for building the Liberty Memorial in the years after the Great War. As much of an imprint as Long left on Kansas City, he may have been more significant in the latter part of his life and career, after moving to Washington state. Longview, Wash., one of the nation’s first planned communities, was named in his honor, and he was a pioneer in the practice of replacing trees felled for the lumber industry with new seedlings.

August Meyer (1851-1905) was born in St. Louis, made a fortune in Colorado’s Silver Boom in the 1870s after founding an ore-crushing mill, then moved to Kansas City in 1881. His Kansas City Smelting and Refining Co. added to his wealth, and he turned his civic vision toward a push for a new park system; he was the first president of the city’s new park board, and was responsible for hiring George Kessler to design that elaborate system. What was once his 35-room mansion on the southern edge of the city is now the Kansas City Art Insititute’s Vanderslice Hall, and Meyer Boulevard is named in his honor.

Thomas H. Swope (1827-1909) was a native of Kentucky who made his fortune in real estate after coming to Kansas City in 1857. While best known for his donation of land that became Swope Park, he also acquired property at 23rd and Locust, on what is now Hospital Hill, and donated the land there for City Hospital, a forerunner of today’s Truman Medical Center.

Thomas H. Swope (1827-1909) was a native of Kentucky who made his fortune in real estate after coming to Kansas City in 1857. While best known for his donation of land that became Swope Park, he also acquired property at 23rd and Locust, on what is now Hospital Hill, and donated the land there for City Hospital, a forerunner of today’s Truman Medical Center.

We gave William Woods (1840-1917) his due in the November issue of Ingram’s archive series, noting the vital role he played in launching a vibrant banking sector hereabouts. But this Columbia-born physician-turned-banker also was known for his generosity with local charities, in particular with a school for female orphans of Civil War veterans in Platte County. It later relocated to Fulton, Mo., and, after he personally paid off the institution’s debt during a period of serious financial difficulties, that became what today is William Woods University.

Annie Ridenbaugh Bird (1856-1937) was a pioneer in KC business, one of the first women to break the glass ceiling when she became president of the city’s biggest commercial enterprise: the Emery, Bird, Thayer & Co. She held that role for 17 years after the death of her husband, Joseph Taylor Bird, co-founder. His philanthropic vision became hers, and deeded land to Mercy Hospital, which sold it to build the Joseph T. Bird Nurses’ Home and School of Child Nursing in 1927.

Jacob Loose (1850-1923) came to KC as a young man and co-founded the Loose-Wiles Biscuit Co. (aka Sunshine Biscuits), which laid

the foundation for the philanthropy he practiced with his wife, Ella Loose. In addition to the 80 acres of land she donated in his

memory for what is now Loose Park, they set up a foundation that operates t day, following the simple diretive: Help the poor and needy children and families of Jackson County and KC.

Indiana’s loss was Kansas City’s gain with the arrival of William Rockhill Nelson (1841-1915). The legendary newspaperman founded The Kansas City Star in 1880, then built up its influence and bottom line so that it could acquire the older, established Kansas City Times in 1901. Two papers made him wealthy, as did his real-estate interests. His estate generated the funds to build the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Indiana’s loss was Kansas City’s gain with the arrival of William Rockhill Nelson (1841-1915). The legendary newspaperman founded The Kansas City Star in 1880, then built up its influence and bottom line so that it could acquire the older, established Kansas City Times in 1901. Two papers made him wealthy, as did his real-estate interests. His estate generated the funds to build the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Henry Perry is hailed as the Father of KC Barbecue, having mastered the art and contributed to a pair of institutions in the city: Arthur Bryant’s and Gates & Sons. But he also practiced charitable giving on a small and personal scale with the fruits of his labor. Once a year, for four hours, he would give away sandwiches to the elderly, the young and those who didn’t have a dime for their next meal, often totaling more than 100 pounds of meat.

Victor Speas (1889-1970) was heir to the Speas Co.—maker of vinegar and products derived from apples—which came under his control at age 21, after the death of his father. He used the wealth from that venture to donate millions to medical research over his lifetime. Various foundations devoted to funding research on cancer and heart disease contributed to what would become Truman Medical Center and MRIGlobal, along with Kansas City Hospice, William Jewell College and other beneficiaries. After his death, his wife donated the family home in Hyde Park to Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral.

Alfred Benjamin (1859-1923) transplant to KC, becoming an executive for furniture companies, including Duff and Repp. But he was actively engaged in efforts to benefit the poor, as president of the United Jewish Charities, which served the needy regardless of their faith. He hired the city’s first social worker to help clients learn to become self-sufficient and join the work force, and reputedly gave half his income to various charities, as well as service as a fund-raiser for others.

The family of Samuel Sosland (1886-1983) fled czarist Russia when he was just four, one of eight children in a classic tale of the American Dream realized. From a West Bottoms home with a dirt floor, he helped launch a journal on the grain milling trade, the gateway to a publishing house, then printing and envelope companies, ventures that created his wealth. Beneficiaries were hospitals, social-services agencies, universities and museums, and he was instrumental in setting up the Sosland Foundation, which continues to issue millions of dollars in grants each year.

William Volker (1859-1947) was a German immigrant who made it big in window shades and home accessories, building up a fortune—and then dedicating the rest of his life to giving most of it away. He provided land, money and books for what is now the Volker Campus of UMKC, and helped found Research Medical Center, the city’s Board of Public Welfare, and Civic Research Institute. He would even receive visitors to his home on Bell Street, assessing pleas of various kinds for financial aid for various reasons. When he died, more than 100 people were receiving some sort of monthly assistance from him.

William Volker (1859-1947) was a German immigrant who made it big in window shades and home accessories, building up a fortune—and then dedicating the rest of his life to giving most of it away. He provided land, money and books for what is now the Volker Campus of UMKC, and helped found Research Medical Center, the city’s Board of Public Welfare, and Civic Research Institute. He would even receive visitors to his home on Bell Street, assessing pleas of various kinds for financial aid for various reasons. When he died, more than 100 people were receiving some sort of monthly assistance from him.

Marjorie Powell Allen (1929-1992) was born into wealth—her father was founder of Yellow Freight Co.—and she was involved with philanthropy for most of her life. Her affiliation with the Allendale Educational Foundation established a pair of day camps for children and what is now the Wildwood Outdoor Education Center. But she’s best known for donating the 809 acres outside of Lone Jack that became the region’s premier botanical garden, Powell Gardens. She also helped found the Women’s Employment Network, helping women move from welfare to employment, and helped establish The Central Exchange.

Larry Stewart provided gifts totaling in the millions, but they were doled out by $100 bill—occasionally, a handful—to people in the

greatest need at Christmastime, and with no grant-writing involved. Lee’s Summit businessman Larry Stewart (1948-2007) for years

generated media attention nationwide—and anonymously—by creating the Secret Santa persona as a way to pay back for the breaks he encountered in life after a difficult childhood. Not until just before his death in 2007 did he agree to reveal his identity, and hundreds of people nationwide have been inspired by his example to do the same each year.

FAMILY TIES

It started with William Thornton Kemper (1866-1938), whose banking legacy was covered in the November issue of Ingram’s). After six generations of Kempers in Kansas City’s banking and philanthropic circles, it’s almost impossible to chronicle the depth of the beneficence that has flowed from the families that built Commerce Bank and UMB into the leading locally owned banks. The most recent, highest-profile standard-bearer for that may have been R. Crosby Kemper Jr., the patriarch’s grandson, who died this year at the age of 86. His philanthropy skewed to the artistic and cultural side, as founder (along with four family foundations) of the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art. He also famously stepped up to save a financially teetering Kansas City Philharmonic in 1982.

Real-estate development created a family fortune for J.C. Nichols (1880-1950), who developed the Country Club Plaza and a wide swath of planned residential neighborhoods that still boast some of Kansas City’s most sought-after residential addresses. The legacy continued with his son, Miller Nichols (1911-2000), a civic dynamo who chaired what is now MRIGlobal, the United Way campaign, and the former Philharmonic Association, to name but a few. His wife Jeanette Nichols and daughter Kay Callison made gifts totaling $1.25 million to help fund the recent expansion of UMKC’s library named in his honor, the Miller Nichols Library and Learning Center.

Real-estate development created a family fortune for J.C. Nichols (1880-1950), who developed the Country Club Plaza and a wide swath of planned residential neighborhoods that still boast some of Kansas City’s most sought-after residential addresses. The legacy continued with his son, Miller Nichols (1911-2000), a civic dynamo who chaired what is now MRIGlobal, the United Way campaign, and the former Philharmonic Association, to name but a few. His wife Jeanette Nichols and daughter Kay Callison made gifts totaling $1.25 million to help fund the recent expansion of UMKC’s library named in his honor, the Miller Nichols Library and Learning Center.

It started with Joyce C. Hall (1891-1982), founder of Hallmark Cards, though his son, Don Hall and daughter-in-law, the late Adele Hall, and now grandsons, Don Jr. and David, the Hall family continues to cast an oversized footprint on giving in the Kansas City area. The Hall Family Foundation, one of the region’s largest, is approaching $1 billion in assets. Joyce Hall and his wife, Elizabeth Hall, and his brother Rollie Hall set it up in 1943 to promote the health and welfare of school-age children, bolster educational institutions, and improve both public health and social welfare, and has devoted hundreds of millions of dollars to causes over the past 70 years. In addition, the corporate philanthropic organization, the Hallmark Foundation, is also a notable grant-maker.

Few companies match the philanthropic commitment of the construction company founded by John Ernest Dunn (1893-1964) in 1924. It has grown to a $2 billion organization that operates nationwide, and Ernie’s sons and grandsons have long committed 10 percent of pre-tax earnings to charity. At the same time, the Dunn Family Foundation funds programs focused on education, health and human services, youth, the disabled, the elderly, ethnic minorities, and community development. Incalculable is the value of the hours that executives from the firm have given to service on local boards of non-profits, and the hours that the Dunn work force has contributed to charitable causes and fund-raising.

Kenneth Spencer (1902-1960) made his money in chemical businesses, and his wife, Helen Spencer (1902-1982), helped channel that into philanthropic causes that have benefited causes in Kansas City and the state of Kansas. Their Kenneth A. and Helen F. Spencer Foundation has been a major donor to the University of Kansas and UMKC, as well as the Nelson-Atkins Museum and the Spencer Museum of Art and Kenneth Spencer Research Library, both on the KU campus. Kenneth’s role as a co-founder of MRIGlobal made that research center a beneficiary, and money has also flowed to Saint Luke’s Hospital, St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, and the YMCA.

Perhaps Kansas City’s biggest-name couple as philanthropists, Ewing and Muriel Kauffman left behind legacies of giving that continue to define Kansas City today. In addition to Ewing’s gift of the Royals to the city, through the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation, the pharmaceutical magnate established the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, which is generally considered the world’s foremost institution for promotion of education and entrepreneurship. His wife’s Muriel McBrien Kauffman Foundation gave millions to help finance the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts, which immediately became a world-class venue when it opened in 2011.

Perhaps Kansas City’s biggest-name couple as philanthropists, Ewing and Muriel Kauffman left behind legacies of giving that continue to define Kansas City today. In addition to Ewing’s gift of the Royals to the city, through the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation, the pharmaceutical magnate established the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, which is generally considered the world’s foremost institution for promotion of education and entrepreneurship. His wife’s Muriel McBrien Kauffman Foundation gave millions to help finance the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts, which immediately became a world-class venue when it opened in 2011.

They have been pillars of philanthropy almost since their business, H&R Block, opened its doors in 1955. Richard Bloch (1926-2004) and his wife, Annette Block, and Henry Bloch and his wife, Marion Block (1930-2013) have been involved in a huge range of philanthropic causes and initiatives. The H&R Block Foundation is the corporate philanthropic wing, and shortly before Marion’s death, she and her husband created the Marion and Henry Bloch Foundation, which immediately launched as one of the region’s top 10 in terms of assets.

“We owe a debt to Kansas City,” because of that business success, Henry said at the time. That foundation supports post-secondary business education, entrepreneurship, health care, social services and other causes. And a $32 million gift to UMKC funded the new Bloch School of Management there. Richard and Annette (a cancer survivor as well) began donating to health-care initiatives after he beat an initial cancer diagnosis in 1978, and their wealth has helped to fund cancer-focused programs and the construction of Children’s Mercy Hospital, the University of Kansas Hospital and Truman Medical Center.

Jewelry built the Helzberg empire, but even after selling the stores to Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway in 1995, Barnett and Shirley Helzberg are still in the business of creating wealth. Only now, it comes in the form of Barnett’s efforts to promote business mentoring through the Helzberg Executive Mentoring Program, and Shirley continues to enrich the cultural aspects of life in Kansas City with her work on a very long list of non-profit causes in the world of art and music. Barnett took over the company in 1962, expanding it from 15 stores to nearly 150 in 23 states before the sale to Berkshire Hathaway.

Jewelry built the Helzberg empire, but even after selling the stores to Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway in 1995, Barnett and Shirley Helzberg are still in the business of creating wealth. Only now, it comes in the form of Barnett’s efforts to promote business mentoring through the Helzberg Executive Mentoring Program, and Shirley continues to enrich the cultural aspects of life in Kansas City with her work on a very long list of non-profit causes in the world of art and music. Barnett took over the company in 1962, expanding it from 15 stores to nearly 150 in 23 states before the sale to Berkshire Hathaway.

In terms of raw dollars—and potentially, in terms of overall impact—Kansas City has not seen philanthropy on the level of Jim and Virginia Stowers, and very possibly may never see it again. A net worth of nearly $2 billion amassed through the founding of American Century Investments had been almost entirely funneled back into biomedical research by the time Jim Stowers died in February of this year at the age of 90. Virginia and Jim Stowers had been cancer survivors, and they made a commitment to combating the disease by founding and funding the Stowers Institute for Medical Research. It was the kind of investment that cities nationwide could only dream of in pursuit of a more vibrant biomedical sector, sparking a huge follow-on by other organizations, elevating the region’s research profile.

The wealth these philanthropists created, the value of their donations, and the entrepreneurial spirit they demonstrated have

defined Kansas City. But their greatest gift of all may have been the example they set for a city: You can’t take it with you, but a big part of you can live on through your generosity.