HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Kansas City’s police officers don’t operate in a silo; they’re part of the community, and need to be part of the solution, a police official says.

Chief Rick Smith was on the front lines during the unrest on the Plaza and consulted with a police commissioner as protests morphed in rioting and assaults on his officers.

“I would argue, personally, that if people want to see a better system and want more layers of accountability to create a better environment, they should look to Kansas City. We’re the only one in the nation like this, and I think we do it pretty well.” -- Sgt. Jason Cooley, KCPD Community Interaction Officer

The nation is at a crossroads with its approach to public safety. The KC Police Department, then, is attempting to play both traffic cop and,

at the same time, avoid getting run over in the national mania to strip resources away from urban law enforcement.

Perhaps more people calling for police defunding would have different views on what’s really needed if they could spend a few minutes with Sgt. Jason Cooley. He’s the community interaction officer for the Kansas City Police Department, responsible for making connections between residents of the city and the 1,300-member department charged with their public safety.

In a wide-ranging interview recently with senior editors of Ingram’s, Cooley ran through an impressive list of the Kansas City’s community-policing initiatives, Chief Rick Smith’s advocacy for programs to support current officers and recruit new ones, and assessed what the city should be doing to both promote its successes—relative to what we’ve seen in peer cities—to create a better foundation for business, jobs, education and the role all three play in getting to a lower crime rate.

A lower crime rate leads to fewer tense encounters between police and criminals. Coming off several weeks of relative calm following the May 30 rioting on the Plaza, Cooley was optimistic, but not entirely convinced, that the city was out of the woods for further outbursts. The violence, which grew out of what were ostensibly peaceful demonstrations against police brutality following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis earlier that week, belied a different agenda by those using Floyd’s death as a pretext for darker motivations.

For those in the former group, Cooley was supportive. He was less supportive for those who came spoiling for a fight.

“We’re all good with peaceful protests, all day long,” he said. “Any enforcement actions that happened to be taken were the result of trying to provide boundaries to the protesters. When they stepped out of those, and on a larger scale, assaulting us, that’s a much higher level.”

More than 240 Kansas City police officers were physically assaulted during that weekend in late May and early June, but the sheer numbers of them exposing themselves to potential violence was in itself the result of Chief Rick Smith’s determined effort to prevent a second night of rioting. He did that by summoning roughly 1,000 officers to the Plaza on Sunday, May 31, and over the course of the next week, that show of force produced the desired response: Protesters backed down here in ways they didn’t around the nation.

More than 240 Kansas City police officers were physically assaulted during that weekend in late May and early June, but the sheer numbers of them exposing themselves to potential violence was in itself the result of Chief Rick Smith’s determined effort to prevent a second night of rioting. He did that by summoning roughly 1,000 officers to the Plaza on Sunday, May 31, and over the course of the next week, that show of force produced the desired response: Protesters backed down here in ways they didn’t around the nation.

“The difficult part for officers in all this,” Cooley said, was that you have police officers who suit up, gear up day in and day out, kiss their families goodbye and come to help serve others.” But those officers are human, too, and Cooley asks why concern over the welfare of protesters isn’t balanced by concern about the police called in to maintain order.

While they exist to protect and to serve, Cooley noted, “sometimes the police need to be served, too; sometimes we need help.” But when police needed the backing of civic leadership, he says, the lack of it was telling. “We understand that, since we were in a battle zone at that time—some partners and upstanding citizens don’t want things to come out just then; we get that. But officers were like ‘Where is our community when we need support, when we need help?’ So yeah, it’s been some tough times. But it’s a job. It’s what we do.”

The question facing Kansas City’s leadership is, what is it prepared to do to improve the climate here? In the current environment, it’s almost impossible to raise the question of why disproportionate outrage is being directed at police while, at the same time, far more people, the vast majority of them young black males, are being gunned down in the streets—and not by police. Cutting police funding, as Cooley notes, isn’t going to help address homicide clearance rates or deter street crime. In fact, he says, just the opposite. “My argument would be for additional funding; we don’t need fewer officers, we need more,” he said. During Smith’s 2½-year tenure as chief, the city has gone from 1,275 sworn officers to 1,350. But the number of officers by itself isn’t the key, Cooley says—it’s the way they are deployed, especially in service to Smith’s commitment to community policing.

“With more officers, we can be more responsive to 911 calls, we can be more visible,” he said. “That doesn’t mean we have to police with an iron fist, but we would be able to enhance community policing efforts.”

Over the previous decade, some of those initiatives were gutted, with corresponding increases in violent crime. Under previous Chief Rick Corwyn, the department had three Police Athletic Leagues. Today it has one. Community Action Network centers have been cut to just two, and the drug-fighting DARE unit has been halved with its staffing. “There’s more we can do with community policing if we had more staff,” Cooley says, and Smith has acted on that very belief.

Among the other initiatives he has supported, Smith has championed placement of social workers in each of the city’s six police patrol divisions, and last year, they produced 2,207 referrals to officers. “That’s huge,” Cooley said. Smith also brought back the community interaction officer roles eliminated under Daryl Forte, then doubled it to have a CIO in place for day and night shifts at each division. Last year, they attended 1,007 community meetings and events.

“They do fantastic work, they are passionate about what they do, and they are highly successful,” Cooley said. Yet those same officers, summoned to the Plaza in late May, were physically assaulted by the people they seek to serve.

For whatever criticisms are lobbed at the KCPD, Cooley says, it’s worth noting that not a single building in Kansas City burned during the late May rioting. That’s something few urban communities can boast, and he believes that Smith’s work with community policing, and engagement of church leaders during the height of the protests, helped create an opportunity to let tensions dissipate. The June 3 Unity March from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art to Mill Creek Park, and the 10-mile prayer chain down Troost on June 19 also acted as civic balm.

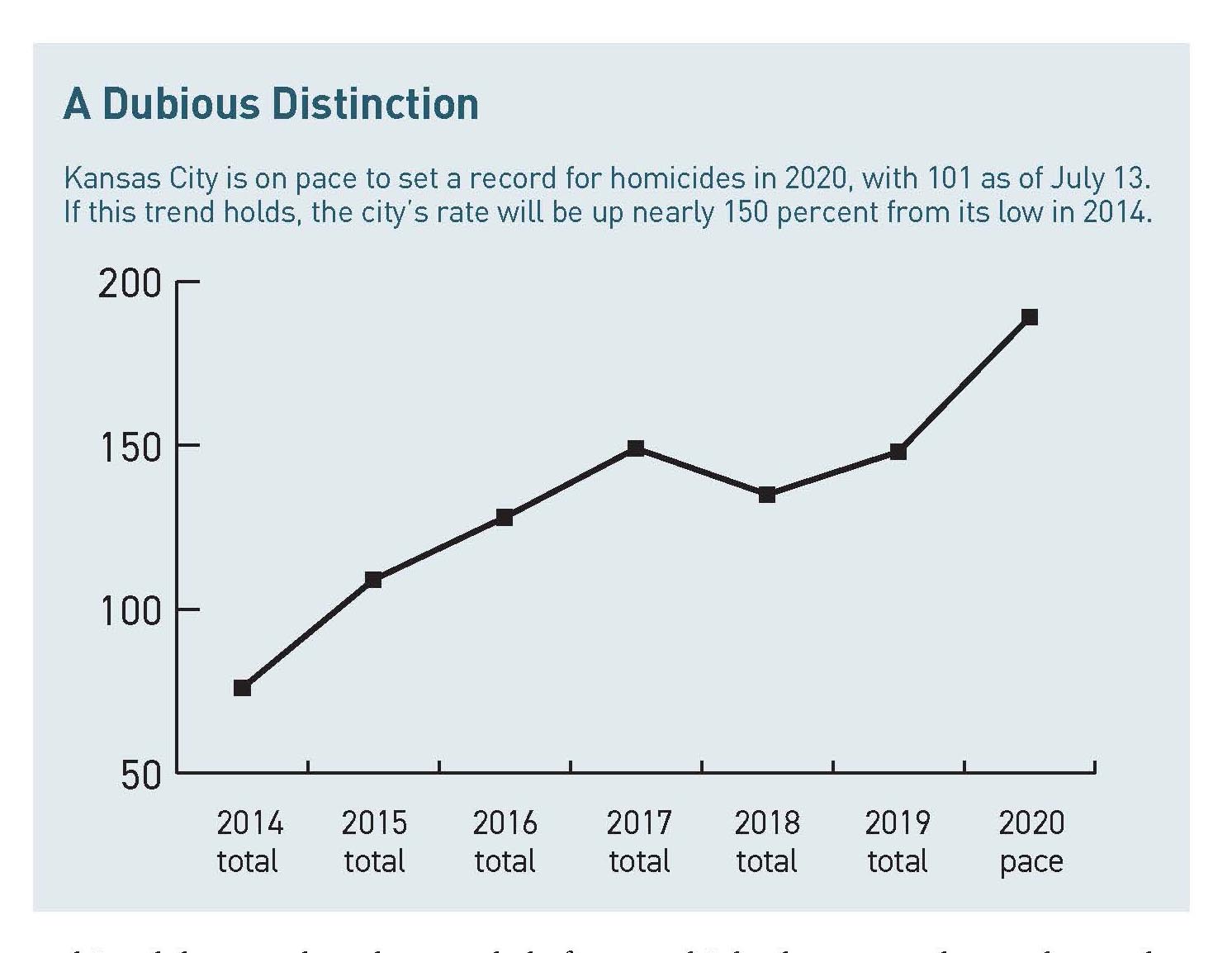

First, however, it must deal with the gun violence, where police are still trying to understand what has placed the city on its torrid pace for lethality. As of mid-July, the city stood at 100 homicides, on pace not just to break, but to shatter a nearly 30-year-old mark of 153.

“What I do hear in some circles it that it’s marijuana, could be marijuana-related,” Cooley says. “In the ’80s and ’90s, it was crack and PCP, now people are killing themselves over marijuana.” That’s an ironic development, given the increasing legalization of the drug across the nation.

But there’s more at work, he says. “Disrespect on a Facebook posts, the social media piece,” Cooley says. The psychologically disruptive response to the COVID-19 pandemic and associated job loss, particularly among low-wage workers, plays a role too. “We even had a recent incident of family members shooting it out,” Cooley says. “Because of everything going on and things we’ve not dealt with in our lifetimes, I think that’s had an impact on people’s mental health as well. So it’s a mix of gangs, guns, social media—these are just trying times.”

Longer-term, though, the city has some work cut out for it on the civic end, not just the law-enforcement end. Currently, there are calls for bringing the KCPD back under local control, having been made a ward of the state during the Pendergast crime era a century ago. That, Cooley says, is precisely a formula for less accountability in law enforcement.

“We have more layers of accountability in Kansas City than any municipality it the nation,” he says. “Around the nation, people are calling for change, they are calling for that change here, but we changed decades ago. I would argue, personally, that if people want to see a better system and want more layers of accountability to create a better environment, they should look to Kansas City. We’re the only one in the nation like this, and I think we do it pretty well.”

The business community, as well, has a role that isn’t being filled now, he believes.

“Why isn’t leadership having a full-on recruitment for businesses to come to Kansas City right now?” he asks. “You have CHOP in Seattle (since disbanded by that city), a whole district where business can’t open because that city is allowing that to happen. Why not reach out to those through the EDC or other organizations to recruit those companies here? It’s a perfect opportunity to bring industry back to Kansas City, and industry equals jobs. When you have jobs and education, our crime rates are going to go down. Let’s talk about how Kansas City can be the heartbeat of the nation.”