HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

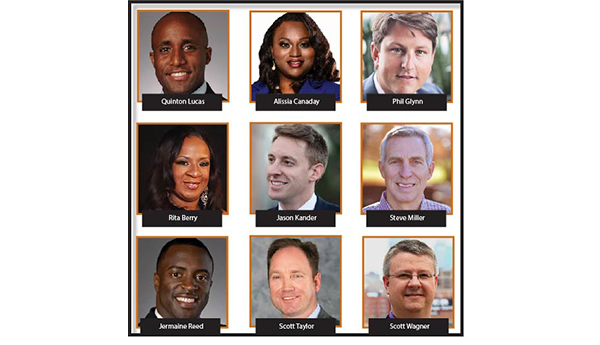

It happened again in the second week of July. Fully two weeks after Jason Kander—former Missouri legislator and Secretary of State, and nearly U.S. Senator—announced that he was launching a campaign to become Kansas City’s next mayor, yet another political-gab Web site was floating his name as a potential White House dark-horse candidate for 2020. That may say more about how the chattering class is assessing the Democratic Party’s need for new blood in its leadership than it says about how far political news travels east of Kansas City. But as Kander reorients his career and takes aim at City Hall, not the U.S. Capitol, that kind of speculation will be dredged up between now and April 2, when a field of nine candidates will be trimmed to two for the general election in June.

Kander can expect to have all comers taking shots at his rapid rise through regional, state and even national politics as a rising star within the Democratic Party—a young, articulate, photogenic lawyer, with a military background that includes combat duty in Afghanistan. It’s an irony of non-partisan municipal elections (most everyone in this field is a lifelong Democrat) that those challenging him in this race have been long-time associates, supporters and even friends.

For voters in Kansas City, it will be interesting to see whether the issue of Kander’s career trajectory becomes a dominant talking point of this race, or whether the candidates are going to differentiate themselves based on their grasp of local issues at a granular level, tenure in office addressing those, and ability to get out and pound on doors.

As Kander himself suggests, they’d better be prepared to discuss intensely local issues—because he will be. “There are a bunch of really good people running for mayor,” says the 37-year-old Kander, who was raised in Johnson County and at one point was the youngest person, and first Millennial, elected to a statewide office in the U.S. “I know about everybody in this race, I consider them friends, and they are people doing this for the right reasons.”

But those up against him should be forewarned. “I only have one way I campaign, and it’s always at 100 miles an hour,” Kander says. “I am excited about this campaign, and if elected, about doing the job. I want to make sure to get out there and do what I’ve always done: Meet people face-to-face and convince them that I can earn this.”

Much is riding on the outcome of this election for the city, the candidates uniformly agree, but that’s especially true for business. In a community struggling to juggle financial chainsaws that include a $2.5 billion EPA consent decree to address storm-water drainage, increasingly vocal critics of public subsidies for development (particularly those Downtown), ballooning cost projections for building the new Kansas City International Airport terminal, a streetcar expansion that probably won’t earn federal funding, public-safety issues and their connection to a police board not under direct city control, unexpectedly large subsidies for the Power & Light District—the list of business-related concerns is long and growing.

Can discussions of remedies for those challenges accommodate sideline debates over whether one candidate’s commitment to the office outweigh his longer-term career interests?

One of Kander’s opponents, Mayor Pro Tem Scott Wagner, doesn’t believe the injection of a candidate stepping in from the national spotlight will change the underlying dynamics of this race. “We still have five sitting council members running, three of which have reached term limit,” says Wagner, who represents the sprawling 1st District in the Northland. “My feeling in all of this is, people don’t care what you had before as far as your office; what they want to know is what you want to do here.”

Kander, he said, will have to answer the same kinds of questions facing other candidates from an electorate that might be somewhat more cynical about candidates now than it was in 2016. In that cycle, national and state-level populists Donald Trump and Eric Greitens won the presidential and governor’s races, but their actions in office left some voters regretting their choices. “The very interesting thing I think is going to be whether people who see a new candidate will ask hard questions about what he plans to do for the city,” Wag-ner said. “What do you know about this city?’ Once the honeymoon is over, you’re right back where we were with the same discussions about the same issues.”

Kander jumped into the race with a long list of endorsements from some large names in city politics, and it immediately prompted the exodus of City Council member Jolie Justus, considered by many a front-runner to succeed Sly James in the mayor’s office. That initial statement, the endorsements and the knee-jerk assessments of political observers in KC lent an air of inevitability to the Kander candidacy, but Phil Glynn, a friend since their high school days—and now his opponent in this race—doesn’t expect to see a coronation ceremony unfolding over the next 9-11 months.

“Honestly, all this has done is change the coverage of the race,” and not the race itself, or the fundamental issues behind it, says Glynn, who has honed his skills in low-income housing development as president at Travois. “One person dropped out. Does that seem like a dramatic shift to you?”

Undeterred by the headlines and predictions, Glynn says that “I’ve been knocking on doors, been on the phone, been at community meetings, and I can tell you that in my experience, in the optics that come up when speaking to the business community, the underlying dynamics haven’t changed—only the way the media is covering it has changed.”

Another of the candidates, Council member Quinton Lucas, isn’t so sure. The Kander Factor “absolutely” changes the nature of this race, he said. “When running for office, we are all thinking of how we distinguish ourselves,” he said. The council experience in the race, Lucas says, means that “all of us have worked on figuring out how to pass and balance a city budget, deal with city issues, but this injects a level of superficiality into the conversation. We need to answer this city’s real challenges.”

His council colleague Jermaine Reed refuses to flinch in the face of Kander’s outside connections and potential ability to raise funds nationally for a local contest. “I applaud anyone who wants to sign up and serve our community in any capacity, school board, council, county offices, to state level or even federal,” Reed said. “It’s not easy to put yourself out there and say you want to run for office, but I do think these discussions need to be around issues and not necessarily personalities.”

Reed, like other council members, believes he has a track record of pro-business success to run on, and welcomes putting that up against anyone, even someone with national-office aspirations. “When I took office in 2011, along with the council and the mayor, we inherited a City Hall that had a ‘Closed for Business’ sign on the front door,” Reed said. “I believe over the past seven or eight years that I have served faithfully on the council and have been able to turn that sign around.”

The ability to capitalize on established momentum, he and others say, will determine the winners in April and the ultimate survivor next June. “We have no time to have on-the-job training or political gamesmanship that continues to be played,” he said. One other dynamic that hasn’t factored into analyses of this race is age: With the exception of Rita Berry, whose campaign is running well behind the others financially and who lacks the name recognition of a council veteran, five of the candidates are either Millennials or among the younger members of Generation X, save for one: Steve Miller.

The KC construction and transportation lawyer and co-founder of Miller Schirger LLC is a former two-term Missouri Highway Commission chairman with a long history of backing non-profit and philanthropic causes. All of those are factors that will help in an election that could turn on questions of experience, competency and demonstrated results.

“Endorsements,” said Miller, “don’t vote. If you look at recent history, the candidates who had the most endorsements at this juncture were not ultimately the individuals that become mayor. Being mayor of an area as diverse as Kansas City takes a special skill set. Kansas City generally likes seasoned, experienced leaders who have committed themselves to this community. I think Kansas City will see the value in this election of having experienced leadership.

Assessing the field, Miller notes that “if you look at the eight still in race, five are between 32 and 38 years old, and two are in their 40s. I sit there at 60, so my age and experience will be a distinguisher from the outset. Every gray hair I have is hard-earned.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described the corporate structure of Travois; it is a for-profit company.