HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

It was a great evening, and not just because some fine wine was consumed. Nearly 20 years ago, at the dawn of a new millennium, Ingram’s gathered 14 visionaries from the realms of transportation, infrastructure, design, real-estate development and public policy. We started with a blank slate, 14 imaginations, and a challenge:

Sketch the Kansas City region in 2050.

Kansas City’s Dream Team, (Standing L-R): Phil Kirk, Jim Calcara, Dan Carey, Greg Grounds, Bob Mayer, Vicki Noteis, Deron Cherry and Rafael Garcia. (Seated L-R): Stephen Nottingham, Rod Richardson, Adam Jones, Rob Pearcy, Peggy Dunn and Joe Sweeney.

Over the course of some hours at The American (I still bear the scars of the bar bill), this impressive group did just that.

A generation later, it’s interesting to see how much of their vision has been realized. And a little disappointing to consider some of the opportunities that have been forsaken by business, civic and political leadership in the years since. (Read this entire feature and enjoy their input at https://ingrams.com/article/KC2050).

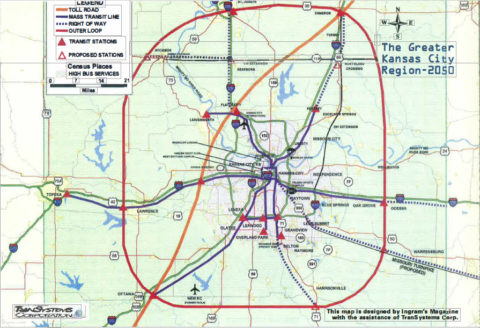

But let’s start with that vision. Look at the map below. It was Ingram’s visual representation of a master plan, executed with the assistance of TranSystems, the transportation engineering firm. It was framed largely around the way people and product might move by 2050. The centerpiece of change, perhaps, was a vision that an automated Chicago-to-Mexico tollway (NAFTA was emerging in this era) could be built—perhaps even funded—through private-public partnerships. It could change the flow of people and goods away from the core of Kansas City, along Interstate 35, and to some degree alter the way we move, not just the pathway.

Could entrepreneurship, rather than relying solely on government funding with its limits, accomplish a new tollway? Well, vision and capital came together in the 19th century to create a latticework of rail lines that still serve as iron arteries of commerce today. And at the high-end going rate of $6 million a mile for a divided highway (plus land acquisition costs), that could be bankrolled with just $9 billion—easily within the grasp of America’s new oligarchs of tech-

nology. (Are you listening, Elon Musk?)

Freed from the congestion of pass-through traffic and with limited access points, the region could create a true mass-transit network that followed existing highway lines, rather than disrupt legacy roadways and arterials, and be far less restrictive in its reach than reviving a technology that passed into history in the 1950s, the streetcar system.

Freed from the congestion of pass-through traffic and with limited access points, the region could create a true mass-transit network that followed existing highway lines, rather than disrupt legacy roadways and arterials, and be far less restrictive in its reach than reviving a technology that passed into history in the 1950s, the streetcar system.

Speaking of rail, we believed back then, and still do today, that the streetcar lines may be better served on an east-west axis vs. north-south. We believe east-west lines transport more workers into the urban core as well as fans to the Sports Complex. The 2026 World Cup organizers might agree that connecting the sports complex to Downtown is a critical element of considering KC as a host city.

The benefits of such an enterprise could change the way we commute, the way we select places to live and do business.

The map also reflects a two-tiered growth pattern of continued southern and westward expansion, in particular. This is combined with the likely redevelopment of aging inner-ring suburbs and the urban core, infused with new vigor to retain and attract residents who long for the vibrancy of a big city’s density.

Perhaps the most interesting feature is the outer ring that just incorporates, into a refined “metro” area, the cities of Lawrence, Ottawa and Atchison on the Kansas side, and St. Joseph, Cameron, Odessa and Harrisonville on the Missouri side.

These roadways may be a gleam in the eye of transit planners, but the growth we’ve seen in 20 years has been realized in and around much of that ring. A trip from Johnson County into Lawrence or to Harrisonville reflects how much of that space between the metro borders of 2000 and today has changed.

It’s particularly interesting to reconsider that new loop in light of some comments made at the 2019 Ingram’s 250 Assembly. Greg Klein, chief executive for Inland Truck Parts Co. in Overland Park, observed that Interstate 435 had effectively reached it capacity, and that it was time to consider the next tier of highway infrastructure, particularly in the sprawling southern region.

On another issue, it seems quaintly naïve, but the visionaries at that table anticipated a coming-together of public policy czars to end the mindless incentives fueling border-jumping business decisions that create few net new jobs. It took nearly a generation for the governors of Kansas and Missouri to declare an end to the Border War (about five times the duration of the Civil War, by the way), and we’ll have to wait and see if this year’s agreements will become the new norm. But, hey, the visionaries were proved right in that instance again.

What those 14 prognosticators missed as they assessed the coming changes for this region was its emergence as a global center of animal-health research, that it would become a much bigger linchpin in logistics and distribution, and that health-care informatics, rather than telecom, would drive more business growth.

Cerner Corp., today the region’s largest private-sector employer, wasn’t mentioned in that session. It had $340 million in sales the previous year, a respectable figure in those days, but one that barely earned its mention among the region’s biggest companies at that time.

As for the other possibilities, well, they remain just that … possible. Whether bi-

state business and government leaders will rally around a vision bigger than a few miles of streetcar line, or if we’ll pursue something truly transformative, remains a question.

The clock, however, is ticking: If the elements of that KC 2050 vision articulated in that roundtable are to be fully realized, it’s past time to get some things in motion.

Leave a Reply