HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

The Kansas City Royals, in typical Royals fashion during the 2015 post-season, come back in the ninth inning and defeat the New York Mets with a 5-run 12th inning, capturing the 2015 World Series championship on Nov. 1.

The five-game spanking of the Mets was the culmination of a years-long rebuilding project directed by General Manager Dayton Moore. Not only did it bring the Commissioner’s Trophy to Kansas City 30 years after the Royals’ last title in 1985, it helped salve the wounds of an oh-so-close seven-game World Series loss to the San Francisco Giants in 2014.

After withstanding a September swoon that tarnished the team’s league-leading record a bit, Kansas City recovered, earning the homefield advantage for the playoffs.

The Royals began by dispatching the Houston Astros in five games with a miracle Game 4 comeback. Just two outs away from elimination, the Royals came stampeding back, then took Game 5. They followed by besting the Toronto Blue Jays in a six-game ACLS series, then made short work of the Mets, often staging late-inning rallies throughout each series.

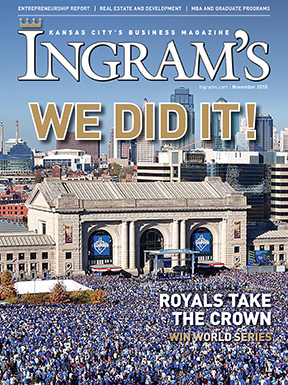

The World Series victory touched off a citywide celebration that wrapped up with a Nov. 3 parade and festivities on a scale never seen in Kansas City: A crowd estimated by authorities at 800,000 choked Downtown streets for a ceremony in front of Union Station and to the south as far as the eye could see.

The issue was slow to gather steam, in not silent throughout 2015, but produced a sudden, seismic result: On Nov. 8, Tim Wolfe resigned as president of the University of Missouri system, and Bowen Loftin followed shortly afterward, relinquishing his duties as the chancellor of the main campus in Columbia.

The run-up to that change was ground-ed in a handful of incidents that students conflated into a narrative of systematic oppression, a story line that critics said didn’t hold up to closer scrutiny. It all came to a head and captured headlines nationwide after a group of black players on MU’s football team said they would boycott an upcoming game against Brigham Young Univ., to be played at Arrowhead Stadium in KC. Cancellation of the game could have left MU liable for a $1 million payment to BYU. A move that influenced the resignation of Coach Gary Pinkel and jeapordized players scholarships.

In the end, Wolfe left the system, Loftin transitioned into a research role at MU, and the board of curators appointed alumnus Michael Middleton as interim system president and Hank Foley was named interim chancellor.

Right up until year-end, the fate of Kansas City International Airport commanded headlines and airtime. In May, a 24-member advisory board appointed by Mayor Sly James delivered its recommendations on changes to KCI.

The group’s verdict: Despite an ample show of popular support for the current configuration and the convenience it affords users here, it’s time for a single-terminal makeover. The projected cost at that time was somewhere north of $1 billion.

In December, the City Council got a better look at what improvements might look like. A study exploring ways to configure a new airport with a large main terminal showed four options. Two would use some of the existing structures—which underwent a $258 million renovation a little more than a decade ago—and two that called for starting from scratch.

The study said it would be cheaper to build new than to renovate: $964 million for the new facility, and between $1.04 billion and $1.19 billion for renovations.

With great fanfare, the city and its project partners rolled out the vision for a new Downtown convention hotel in May—a $310 million, 800-room Hyatt. When they made that announcement, they indicated that the city’s maximum exposure on the project would be capped at a little more than $50 million.

Details released since then suggest that the public investment will be considerably larger, perhaps as much as half the total cost, sparking opposition from public-interest groups who say that’s a price that a cash-strapped City Hall cannot afford.

Those groups have pressed for a public vote on the city’s role in the project, more recently valued at $310 million. Developers say a vote would delay the project and put it at risk with higher construction and financing costs, especially if the economy sours.

In December, a group called Citizens for Responsible Government filed a lawsuit in Jackson County Circuit Court, seeking to compel the city to let voters have their say in the April elections.

With construction progressing thro-ughout 2015, Kansas City’s $102 million streetcar system was drawing closer to carrying its first passengers as the year’ end approached. In November, the first unit arrived and was soon undergoing tests, and the second of the four units arrived in December. The 2.2-mile starter route is expected to begin operations in early 2016.

But it’s been a bumpy ride to get there. The streetcar was conceived with a 2012 vote that was structured—critics would use the word “rigged”—for a small group of affected property owners. It passed with the approval of just 318 votes. The city almost immediately began moving forward on plans for additional service, but in August 2014, voters weighed in with a resounding “no” to plans for establishing another transportation district to extend the starter line.

A defiant Mayor Sly James nonetheless declared that “we’re not going to let the starter line be the end of the line for this thing. It’s ridiculous to think that.”

Easily the biggest entrepreneurial success story in Kansas City over the past third of a century is Cerner Corp. Launched by three former Arthur Andersen consultants in 1979—Neal Patterson, Cliff Illig and Paul Gorup—it has become a global supplier of health-care information systems.

In the past two years, the hiring boom at Cerner has propelled the company to the status of the region’s largest employer, with more than 10,000 in the area; 22,000 overall.

That figure soared significantly in February, when Cerner completed the acquisition of Siemens Health Services, absorbing 6,000 employees on the biggest “hiring” date in its history.

Now . . . where to put everyone? That question is being answered in south Kansas City, where Cerner announced in July that it had broken ground for construction of the first two buildings at its $4.45 billion Three Trails Campus. When finished in 2025, that site will house more than 16,000 employees.

It’s been happening for years, but one of the most significant axes to fall at Sprint Corp. was being honed again in October, when the telecommunications giant confirmed that it was studying an aggressive cost-cutting plan to cut up to $2.5 billion in expenses, with thousands of layoffs likely companywide.

Many of those would come at the world headquarters in Overland Park, which has already seen the work force cut in half from its peak of 14,000 a decade ago, when it was the region’s top private-sector employer.

It’s been a decade of challenge for Sprint, where challenges have been in ample supply since the Nextel merger in 2005, a union hailed by analysts in retrospect as not just a bad deal, but by Forbes as possibly one of the worst acquistions ever.

In the years since, the company has gone through a succession of CEOs as well as new majority ownership. Japanese-held Softbank bought a 70 percent stake of Sprint in 2013, and Marcelo Claure, a native of Bolivia became CEO in 2014.