HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Going Global: KC's Growing International Economy

Matt Wood didn’t get into business in Kansas City thinking of himself as an exporter. When he founded SCD Probiotics in 1998, he was anticipating domestic demand for the company’s microbial product lines—like those for maintaining human health, or for use in raising cattle, horses and poultry, or for cleaning and degreasing agents.

But for someone who studied microbiology in Central America and Japan, and who had contacts around the world, it didn’t take long to realize that the marketplace was much bigger than he’d originally envisioned. Much bigger.

“It wasn’t by plan or strategy,” Wood says of the company’s current client structure. Last year, Wood estimates, 85 percent of the product SCD shipped was to other nations, and the company was named Missouri Exporter of the Year.

“Before I started the company, I had traveled quite a bit, working with the technologies and traveling through 20 different countries,” he said. “I’d built a Rolodex of companies. When I started, people were contacting me from overseas, and we pretty quickly developed a system to allow foreign companies to license our technology.”

The approach was hands-off from SCD’s perspective, he said. If someone wanted what the company had to offer, they could make the investment, secure the regulatory approvals needed on their end, and earn the license. About all he had to worry about was filling the pipeline.

Going global has imposed strategic and tactical demands on his company, things that many area business leaders don’t have to deal with—international business travel, conferences overseas, hiring salespeople who are bilingual, and adjusting the hiring profile. “Having people on your team who had never been out of the States,” Wood says, “is often not a good strategy.”

Those business factors, though, could well apply to more companies in the Kansas City region if they simply adopted a more global view of their products or services, export professionals say. The U.S. may be the world’s largest single consumer market, but even its $17 trillion GDP pales in comparison to an aggregate global output of $71 trillion. You can find a lot of buyers within that $54 trillion difference.

And for those seeking entry into foreign markets, this region has no shortage of assets—public, private and non-profit. But any deep dive into the export process starts with an understanding of this region’s strengths, and of the kinds of companies and business sectors that are reaping the benefits of truly engaging in a global economy.

Exports are one of the few areas where Kansas, with half the population of Missouri, goes toe to toe with its larger neighbor: In 2013, the dollar value of exports from those states were nearly even—Missouri weighed in with $12.9 billion; Kansas with $12.5 billion, according to figures compiled by the International Trade Administration, an office of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

The bulk of the region’s exports has historically gone to Canada and Mexico, which isn’t too surprising, given the common borders they have with the U.S. But the biggest change in the export balance has been China’s demand for products from Kansas, reflective of that nation’s needs to fuel growth in manufacturing and transportation, as well as feed a population of 1.35 billion. Since 2010 alone, the Chinese have tripled their purchases from the Sunflower State, and last year overtook Mexico as the state’s second-largest export market.

And they’ve done it without significantly tapping into one of the state’s biggest exports: general aviation aircraft, a sector that continues to be hobbled by a prolonged downturn.

“Manufacturing and ag are probably still at the top of the list” for the state’s exports, said Steve Kelly, deputy secretary of commerce. “In 2013, the leading classifications of exports were aircraft and parts, cereal and metal by-products. Those 2–3 have been at or near the top for some time.”

Once a worldwide decline in demand for small aircraft reverses course, Kelly said, Kansas will be well-positioned to increase its export reach. “That market has not come back like the others,” he said, with numbers that “are nowhere near what they could be if we got back to normal.” But he’s confident that a lack of significant competition in light-aircraft production in other countries will eventually bode well for plane manufacturers in Wichita.

The reigning king of exports in the state: agricultural products. Of the state’s top 10 export products, cereal grains, grain products, meat and hides accounted for 84.6 percent of the aggregate value, the ITA figures show. The world’s collective appetite is showing up in those lines.

“As the economic situation of people improves worldwide,” Kelly said, “not only is demand for higher quality food and higher protein levels increasing, there’s more concern about quality that comes into play.” That goes for other consumer goods, he said, but especially food. Thanks to a well-established reputation for food safety and regulation, U.S. companies have a strategic advantage in selling products that others are going to eat.”

And even if you can’t eat it, there are still some positive connotations to Made in America, Kelly said. “People feel a reliability and quality attached to that, where in many countries, they don’t have that for their own domestic production. We have a reputation for quality products.”

Missouri’s exports are considerably more diverse, led by motor vehicles and parts, which accounted for 9.7 percent of the state’s exports last year. But its Top 10 products accounted for just 28.2 percent of the export dollar value in 2013. Overall, slightly more than half the state’s output went to the same three trading partners—No. 1 Canada, No. 2 Mexico, and No. 3 China. They combined to buy $6.8 billion in Missouri products, more than half of the state’s export total.

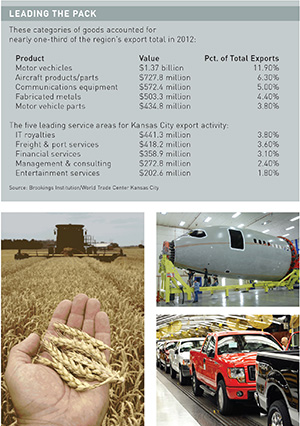

In the middle of all that activity sits the Kansas City region, which yielded nearly one-third of the combined two-state export output in 2010—$8.1 billion. Exports accounted for one dollar in every 12 out of the region’s gross domestic output, according to figures compiled for the Brookings Institution.

Leading the way for this region was transportation equipment, with $1.3 billion in export value; chemicals, at $960 million, both with strong year-over-year increases from 2009. Business services was third at $890 million. As with both Kansas and Missouri, Kansas City’s No. 1 export market was Canada, with $258.2 million in goods shipped. Germany, however, was second, at $50.1 million, while China and Mexico, at $39.4 million and $39.1 million, were only slightly ahead of Saudi Arabia’s $37.6 million.

The metro area’s exports reflect two of its primary strengths, said Jacques Lebrument, business research analyst for the World Trade Center Kansas City.

“Kansas City is an innovative city—a city of thinkers,” Lebrument said. The region’s strengths in business services and royalties—a combined $1.44 billion in exports—reflect the output of companies like Garmin and Cerner Corp. in a knowledge-based economy, he said. “It’s not just the products that are exported that we’re known for,” Lebrument said, “it’s that entrepreneurial spirit.”

The export business here also reflects the kind of business-sector balance that has long been a cushion for the Kansas City economy.

“There’s not one industry that dominates, and that’s beneficial for companies on the export side,” said Regina Heise, Kansas City’s office director for the Department of Commerce’s U.S. Export Assistance Center. “Agribusiness continues to be a really strong market for companies in this area, but there are lots of opportunities on the equipment side, as well as the commodity side.”

With more than 2.6 billion people between them—more than a third of the planet’s population—China and India have been particularly strong markets for technology and infrastructure. Kansas City’s contributions to all those sectors keep this office busy.

“Because we have that business diversity to begin with, the opportunities that companies are seeing is similarly diverse,” Heise said. “The great thing about this office is that with so many companies, the challenge is the large variety we deal with, unlike Wichita, which might be far more aerospace and ag. Here, they’re all over the map: Services, agribusiness, health-care equipment, renewable energy.”

On the infrastructure side, she cited the example of China’s insatiable appetite in the transportation sector: “They’re building 97 new airports by 2020,” she said, generating demand for engineering and construction goods and services, as are its needs for telecommunications and energy.

So how do companies here tap into all of that?

Jay Devers has a front-row seat watching the evolution of the logistics sector in Kansas City. He’s in charge of local market development for Bestway International, a global company that provides road, rail, sea and air-freight services, as well as customs assistance for companies doing business overseas.

“We’ve been really lucky; almost 100 percent of our business is international,” Devers said. “When international markets surge up, like they have for several years, we get to feel that more than others. But I’ve been amazed that so many of our clients’ revenue shares have shifted to international.”

Among the factors that would-be exporters need to consider is the amount and cost of compliance, an area that changes rapidly, Devers said. “In my experience, that’s about every six months,” he said. “I just had a call from a Lenexa customer, and their compliance department unleashed a 14-page SOP for every single shipment they are shipping, just to satisfy the current regulatory/compliance reporting environment. There have been lots of jobs created in the past three or four years for compliance people.”

But, he noted, when it comes to exports, government offices tend to be more accommodating than, say, the IRS or EPA might be. “Our government resources are pretty helpful and very trade-friendly, so if they catch you making a mistake, whether it was on purpose or unintentionally—and most are unintentional—as long as you can demonstrate that you’re aware of the problem and taking steps to correct it, they’re pretty lenient.”

The flip side of that, he said, is imports. “I don’t think the same can be said” there, Devers said. “We had a situation last fall with a shipper who made an honest mistake on a filing, and it triggered a $10,000 fine.” That was negotiated down to $500, he said, “but if you’re doing business, you do have to be diligent, you can’t ignore what’s going on.”

Kelly, with the Kansas Commerce Department, said any export undertaking starts with a company’s understanding of its product: “How competitive can your product be? What are the cultural differences and sensitivities? What may be excellent in one market may be offensive in another,” he said. “Do your research. Look into protecting your intellectual property, because the laws there and here are very different.”

Other factors to be assessed are production capacity, human resource capacity, levels of competition from other exporters into a foreign market, and building relationships within a network of organizations that can provide assistance, which in many cases is without cost.

“We have folks in locations around the state who can identify what we can provide for services and give direction on other services that are available statewide, some that are available from the U.S. government, or international trade services,” Kelly said. “We’re not an end-all/be-all, but if there’s something we don’t have the capacity or resources to do, we can provide and direct someone to that resource.”

One of those resources is Lebrument’s WTC-KC, which can provide in-depth analysis of potential markets. The center can generate a heat map that offers guidance on a number of factors. If you sell a particular piece of industrial machinery, those documents can tell you whether India or Indonesia is a better export opportunity for that gizmo, based on such varied factors as political stability, economic trends, trade balance history and the like.

Those in export-related services say there’s considerably less emphasis on imports here, and for good reason: Exports mean dollars coming in; imports send them overseas.

Narbeli Galindo sees the export situation here from two perspectives: as owner of a business that imports clothing, accessories, rugs, artwork and other goods, and as president of the International Trade Council, which develops and conducts trade education programs.

As an importer, she says, “I tend to work with one-of-a-kind things,” and her business success has come from foreign companies “looking for markets where they can expand faster at lower cost. My products are things you cannot find here. So for me, it’s uniqueness. But when it comes to importing, overall, there’s a much higher percentage of imports now than there used to be.”

The ITC is another of the resources that can help business owners on either side of the import-export equation, but especially those local companies seeking new markets.

After moving here from the New York area in the late ’90s to work for Sprint, she said, she decided to launch her own importing business and aligned with the ITC immediately. The changes since then have been profound.

“When I moved here, there was a lot of interest and curiosity about seeing how to work with different markets, but it was not as strong as it is now,” Galindo said. “The economy has changed a lot, and there’s more interest in seeing how companies can expand and increase revenue.”

Part of that, professionals say, is because business owners learned during the 2007–2009 recession that even the world’s largest consumer market might not be sufficient to maintain their desired volumes. As a result, Galindo said, the ITC is “getting a lot of interest in seeing how things work in different markets, especially Asia, China and India” with everything from manufacturing to consumer goods.

Among the global conditions that any export-minded business owners needs to consider, professionals say, are the impacts of booming middle classes, particularly in India and China. As those ranks swell, higher wages will be one consequence, as will appetites for finer goods. That, combined with energy costs that never seem to go down for long, if at all, is rapidly eroding the long-time advantage that had made them targets for off-shoring of manufactured goods. The U.S. is not only becoming competitive in that regard, but with quality as a key determinant.

“The cost of importing from China has really gone up over the last four to five years,” Devers said. “To move a container from China, I can’t put my finger on it right away, but it’s up 15-20 percent if not more over the past three to four years. When I’m talking with folks not familiar with those issues, if that box of freight is $5,000 to move from Shanghai, and you have 10,000 of them, if you can work that cost to $3,500 or $4,000 by near-shoring, that’s huge.”

Kansas City also enjoys a rapidly expanding logistics sector, and the ability to air-freight product overnight to virtually any U.S. port is a distinct advantage for exporters compared to their counterparts on either coast.

“There’s no better place in the country to have freight leave a shipping dock and be on its way to a port,” Devers says. “We’ve got so many awesome resources like the manufacturing talent pool, that’s why so many are looking to international sales as a growth area.”

And for trucking and rail, he said, the new intermodals are also a huge advantage for Kansas City.

Kelly said he saw shifts in the types of activity, especially with products that can be imported and finished in the U.S. “From the manufacturing and production side, the efforts to bring back more manufacturing to the region that had drifted offshore and establish plants here, there are opportunities, and we’re trying to pursue some things with companies that are importing products. We see ways we can identify substituted supplies of inputs that are domestic and from Kansas.”

Galindo, the importer and ITC president, is also optimistic.

“Since I’ve been here, and in nearly 14 years as an importer, it’s incredible how the Kansas City area is becoming so well-known now internationally,” she said. “Not only by many companies expanding to different areas, but with the animal-health corridor and pharmaceuticals, the greater Kansas City area is getting to be known by European corporations where people realize what we are and what we can offer.”