HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

February 2021

If the past year has taught us anything, it’s that unparalleled commitment to patient outcomes, at a time like this, produces results at the highest levels when teams are working as one. In this fight, no individual provider is going it alone.

If the past year has taught us anything, it’s that unparalleled commitment to patient outcomes, at a time like this, produces results at the highest levels when teams are working as one. In this fight, no individual provider is going it alone.

For 18 years, Ingram’s Heroes in Healthcare program has recognized exceptional individual achievement in a range of healthcare roles. Teams, though, are harder to view through such a lens, because they come in operational units (daytime ICU nurses for example, or operating-room physicians and support staff) they come in entire departments, they come at the leadership level, they come in skill levels (clinical and non-clinical staff), they come as an entire organization.

And the larger that organization, the more sophisticated the team structures and communications channels must be. The Kansas City area, from Topeka to Sed-alia, has 13 medical centers that each admit more than 10,000 patients a year. At that level, engaged, collaborative

and high-functioning teams are a must, hospital executives say. That dynamic becomes even more critical during a pandemic, when medical providers have been more stressed—as individuals, as systems—than any in our lifetimes.

Ensuring the right team composition may sound like a priority, but it can’t happen without a key prerequisite: the pieces in place that can be assembled into new teams or new missions for existing teams. Even before the pandemic, health systems were facing nursing shortages, said Amy Peters, chief nursing officer for Truman Medical Centers and University Health

“The demand for additional nurses was only exacerbated by COVID-19,” Peters said. “Without the commitment to supporting their fellow nurses and patients, we would have experienced significant staffing shortages that would have affected our ability to fully support patient care.”

Early in the pandemic, she said, “our primary focus was ensuring that we had the appropriate level of staff to provide safe, quality care to our patients. With guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention changing rapidly, nursing staff and leaders throughout our clinical areas remained flexible to shift gears to provide needed support and follow guidelines to protect the health of patients and staff.”

Even after those teams were assembled, their composition had to change as the risk profile changed.

“When, inevitably, some members of the healthcare team started to personally experience the impact of COVID-19, our nursing staff once again stepped in and supported hospital services to ensure seamless delivery of patient care, meals, housekeeping—all essential services that touch our patients,” Peters said. “The pandemic mobilized clinical staff who hadn’t worked in traditional bedside roles for a while to complete refresher training and, once again, assume responsibilities in patient-facing areas.”

At the largest of the regional providers, The University of Kansas Hospital, the focus on high-performing teams has been a core operating value for more than 20 years, says Tammy Peterman, the parent health system’s market president in the Kansas City area. She also sees that team performance through various lenses in her roles as chief nursing officer and chief operating officer for the 970-bed main hospital.

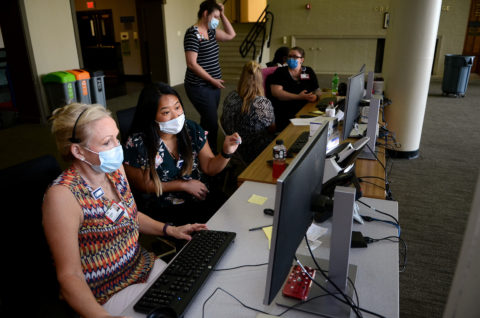

“The pandemic created the demand for roles not typically needed within a health system,” Peterman said. “Contact tracers, staff to swab patients as part of COVID testing, staff to check temperatures of everyone entering the facility, and individuals to field calls coming into the hotline from staff, physicians and patients looking for the most current, fact-based information. Hundreds of staff, clinical and non-clinical, stepped forward with the skills needed to fill these various roles and enable optimal patient care in the safest possible environment.”

Meeting the initial surge required one level of team-building, but even that construct had to change as the virus ran its course, new treatment methods were discovered and vaccines became available.

Hospitals and health systems, she said, have long histories of providing influenza vaccinations for staff and patients, but COVID vaccinations presented challenges not seen before—the requirement of two doses to reach optimal immunity, the logistics of keeping those being vaccinated socially distanced, the coordination of vaccines from two manufactures with different storage requirements, and mandated reporting to the state and national agencies.

“Consistent with the culture, a team of nurses, pharmacists, staff from Information Technology, the Emergency Management Team, and the University came together and developed a plan,” Peterman said. “From an IT perspective, they built an app which was far ahead of what others were doing to support appointment scheduling, documentation and tracking of the vaccinations being administered. Logistically, they laid out a sequential process to safely move staff and patients through several stations, from arrival, to check-in, to vaccination and a 15-minute check for any unexpected reactions. When fully stocked with vaccine, the system can easily move 1,500 patients through in a 10-hour day.”

Because of that team culture, Peterman says, the health system has weathered the pandemic and emerged stronger for the challenge. She saw that play out most vividly in the critical first few months, when the hospital had to greatly expand telehealth services and quickly put in place drive-through swabbing facilities as the need for vastly greater COVID-19 testing increased.

Patient care, by definition, is the result of an amazing team, Peterman said, clicking off a roster of roles including doctors, nurses, therapists, pharmacists, laboratorians, environmental and dietary staff, transporters and more, all coming together to support the patient and family from a clinical and a personal perspective.

Another team dynamic in the region is at work on a much larger scale.

“Kansas City is a unique and special place,” Peterman says. “The other concept of team has been the way we work together as healthcare organizations. That’s really important because I don’t know if everyone outside of health care understands this.”

She has worked more closely than ever with peer executives like Charlie Shields at Truman Medical Center, Julie Quirin at Saint Luke’s Health System, Stan Holm at Olathe Health, and many others. “And we work together as a team,” Peterman said. “That’s a remarkable trait for healthcare organizations who traditionally have been competitors. I believe we’ve become better friends because of this. When we have to rely on one another for how we do things together, that’s an important trait, and it’s also indicative of our city.”

The city itself, she said, was part of it.

“This city has come together in pretty remarkable ways as well,” she says, noting the meals donated to staffers who had to work during the Super Bowl. “I believe the community, at some levels, is part of our team, and they have supported health-care organizations through this like they have at no other time.”