HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

This, according to the Census bureau, is what the value of education looks like. Over the course of one working lifetime:

• A high school graduate can expect to earn $1.2 million.

• A bachelor’s degree, on average, produces $2.1 million.

• A master’s degree ticks that up to $2.5 million.

• Doctoral degrees average $3.4 million.

• And for professionals like doctors and attorneys, $4.4 million.

Figures like those should pretty quickly end any discussion about whether a college and post graduate degree has retained its value, even at a time when the costs of higher education are being characterized as out of reach for too many Americans.

But there’s one more level of education worth exploring: The MBA. According to a study last year by the on-line salary specialists at PayScale, a master’s in business administration from any one of 28 programs across the country—private and public—could expect to generate more in lifetime earnings than even the $4.4 million at the top professional tier.

That’s a powerful statistic, especially considering that some of the public university programs on that list are rarely mentioned in the same breath as degrees from a Harvard, a Stanford or a Wharton School.

That same study found that even programs considered sec-ond- and third-tier are producing degree-holders whose lifetime earnings potential vastly outperforms averages for other levels of education.

And yet, in recent years, academic journals and industry white papers have raised the question of whether the MBA value proposition remains as robust as it used to be. Some critics argue that MBA programs rely too heavily on historical data analytics and backward-looking processes. Others believe the compensation advantage is eroding as costs for MBAs rise.

Some even wave the diversity flag, arguing that because dis-proportionate number of MBA graduates are white and male, their addition to the corporate ranks adds to the challenge of making a company’s leadership look like society overall.

All of which raise a question: In an era where corporate education reimbursements have yet to recover from the recession-era cost cutting, and where aggregate student debt nationwide is fostering cries of unsustainablility, is the MBA degree retaining its full value proposition?

“I strongly believe that, as long as there is business, there is value for the MBA,” says Mahendra Gupta, dean of the Olin School of Business at Washington University, whose school’s MBA program is the only one of those aforementioned 28 from either Missouri or Kansas. “Over time, the need for business education has morphed into different specialties, and that’s where you start looking at the MBA,” Gupta said. “Do you have one with an emphasis in some of the new needs like data analytics, or innovation or entrepreneurship? You have to start looking at the different facets of what business is emphasizing and where they are looking for new leaders.”

Based on observations in Lawrence—that MBA holders from the University of Kansas are rising quickly in workplace leadership roles and reporting high levels of job satisfaction—“the value proposition of the MBA remains strong,” said Catherine Shenoy, the business school’s director of MBA programs. More globally, she points to the Alumni Perspectives Survey conducted each year by the Graduate Management Admission Council. The 2015 edition reports that 90 percent of MBA holders credit their graduate management education with increasing their earning power, and four out of five said their graduate management education offered opportunities for quick career advancement.

At Park University, the Kansas City area’s largest MBA program in terms of enrollment, program director Michael Becraft believes that the value proposi-tion of the credential itself hasn’t changed that much. But, he said, “the rise of other specialist and practitioner degrees pro-vide students more options when seeking a business-related graduate degree.”

Still, “the MBA remains the credential of choice for those seeking to solve problems in an interdisciplinary model in a variety of organizational settings,” Becraft said. “While a student might seek a degree in a precise business discipline, such as finance or management, the largest problems of the organization require the ability to rapidly use a broad intellectual toolset to conceptualize the problems and drive improvement.”

Like Gupta, Dan Falvey of Baker University’s School of Graduate and Professional Studies sees employers em-bracing the more practical side of what an MBA offers.

“What I’m finding is that employers have begun looking not just for people who have completed their MBA and understand how to do regression analysis or analyze big data, but how to apply that learning to identify the next big thing for their organization,” Falvey said. “Rather than the skills and knowledge that employers have typically assumed an MBA graduate had and that the organization valued, now there is much more interest in how these graduates are able to apply that.”

One factor that has eroded the value of an MBA has nothing to do with the degree itself, Gupta noted. “In terms of value, it’s a challenging issue,” he said, but the salaries for MBAs have not increased in proportion to other areas, such as health care or housing. “It’s not that the MBA does not produce a good salary,” he said, “but historically, we have seen, and many argue, that MBA graduates are not making as much as they used to make relative to other costs. But it is still adding a very significant value for people coming in for different disciplines.”

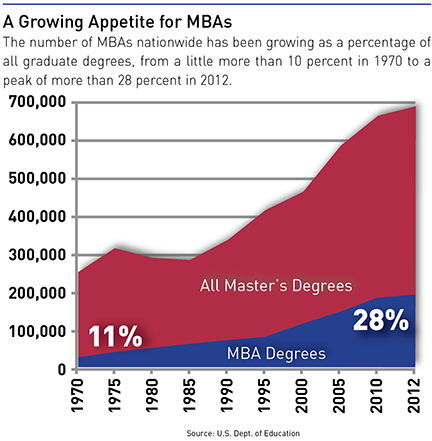

At the end of the 1970-71 school year, the nation’s universities issued 26,490 MBA degrees. Just 10 years later, that figure had more than doubled, to nearly 58,000, while the numbers of master’s degrees overall rose just 28.3 percent.

The rush was on: With students seeking certifications that could help fasttrack their career interests and income,

universities across the nationimplemented new programs or added new program lines to get a piece of the increasing demand. On one level, that competition helped hold down the costs of securing the degree. But on another, some institutions were entering spaces without the right faculty or programming—and a few were serving as little more than paper mills with the degrees they were pumping out.

By 2013, the proportion of MBAs issued among all master’s degrees had peaked at more than 28 percent, up from 11.5 percent in ’71, making it the most common master’s degree issued nationwide.

“The number of MBA programs has grown rapidly because the skills learned in an MBA program are so valuable,” said KU’s Shenoy. “Unfortunately, some MBA programs have entered the space to make money and not to offer an education. It’s very important for a prospective MBA to be able to assess the education he/she will receive.” And one of the best ways for students to choose a program, she suggested, was to look for program accreditation by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business—something held by fewer than 5 percent of the world’s 15,000 schools of business.

What has happened, said Gupta, has “absolutely” reflected issues of supply and demand. To be truly valuable, he said, an MBA “must be well-recognized and supported by a brand. We have seen in the past 20 years too many schools and programs starting MBAs, and those three letters, MBA, have become very diluted. In many ways, I don’t think they carry the same cachet or value. Where you got the letters from does still carry a cachet.”

The upside of program growth, at least at established brands, is that rather than an advanced degree in general business, students can dive deep into specialization—an MBA with an emp-hasis on accounting, for example, or entrepreneurship—even in petroleum management. The evolution of the exec-utive MBA track, often built around working executives who remain employ-ed during their studies, has been a powerful incentive to attract students who aren’t in a position to give up their incomes for a year or two.

Even now, new programs are coming on-line. UMKC’s Bloch School of Management, for example, is rolling out a one-year, full-time program to complement the part-time and EMBA structures. “The reason for that is, there are a lot of businesses in town saying they wanted that,” said Tess Suprenant, director of graduate careers services there. “They wanted a pool of talent that would come in from perhaps around the country, but definitely from around the region—high level, trained, ready to move into accelerated leadership positions.”

It may seem like a small thing—whether one secures an MBA in a single year or through a two-year part-time process—but Suprenant said there were critical distinctions that companies make when assessing MBA-holding job candidates.

“If you look at traditional full-time MBAs, companies recruit completely differently from full-time than from part-time,” she said. “Usually with full-time, which is pretty intensive whether it’s one year or two years, a student often has to drop out from a daytime job.”

For someone in a professional field, that can entail quite a gamble, she said. But it’s one with a payoff: “Companies tend to recruit them differently because they know that these are forward-thinking students” willing to take calculated risks. For full-time students, companies often have rotational programs that offer sam-ple views of the entire organization, she said, so they can quickly fast-track their hires to upper-level management. “They often don’t look to part-time students for these opportunities,” Suprenant said.

Gupta noted that many schools had created specialized master’s programs as a bridge between undergrad business degrees and the MBA.

“Look at the master’s in supply-chain management,” he said. “That was not really something on the radar of people 15 years back. Now, many have it because companies are saying they want somebody not just with a systems approach that systems engineering used to teach, but somebody with a broader business understanding that focuses on supply chain management.

“They’re willing to look at that rather than a more experienced and more ex-pensive MBA. One can argue that OK, for the MBA, that’s not good news,” Gupta said. “I look at differently: It allows you to sell to companies in multiple ways. The MBA program may well in those cases morph and create new specializations and you can try to target those companies in a different way with the skill sets needed.”

Another change Dan Falvey noted was the way emloyers are assessing MBA offerings.

“Some of these first-class employers of choice are looking differently at the programs that their students want to pursue,” Falvey said. “It used to be, if you could show a vice president at Sprint that a higher degree could not just prepare you for new role, but enhance the skills you use in your existing role, they’d approve. Now, we’re seeing that students, prospective students—and we never saw this in the past—are saying to recruiters, “are you ACBSB-accredited? That’s a big change.”

And an important one, because while accreditation can be resource-draining and costly, once in hand it’s a significant marketing edge for a program. Especially as companies pay more attention to accreditation. The only problem with that process, Falvey said, is that the accreditors need a little updating, as well.

“Look at questions about the number of volumes in your school library,” he said. “We have volumes we’re working frantically to reduce—over half of them are now digital, accessible by anybody, anywhere, who’s enrolled at Baker, and we have students all over the world. We have one in Bahrain who can access over half the documents in our virtual library, whereas if we had volumes and volumes still stacked in there, they would be useless to him.”

One of the biggest recent changes in the focus of MBA programs has been generated by companies asking schools to produce graduates who can make immediate process improvements across an organization, administrators say.

“While the MBA has always been a quantitative credential, the scope of data that can be collected/stored and the ad-vancing sophistication of modeling tools show that data-driven decision-making has hopped to the forefront,” said Becraft. “These lead to broad curricular shifts whereby an MBA graduate might not be creating a system, but improving processes and generating organizational change based upon data available as a result of a system.”

With any academic credential, he said, Park must be attuned to work-force needs. “Given the nature of Park’s student population, we are fortunate that our students—already solidly employed—have prompt feedback from employers about their needs and the ability to reach faculty coordinators who are required to maintain currency with-in their assigned fields of specialization,” he said.

What’s changed among companies seeking MBA graduates is a willing-ness to resume at least some of the financial commitment they once made to their employees with educational reimbursements. Many companies scaled

back or eliminated that benefit altoge-ther, and while in some instances it has ticked back up, in many more, it hasn’t returned at all.

And more are taking long, hard looks at this long-term investment.

Because companies have cut back on such training expenses, Gupta said, “they are looking for people who can hit the ground running, they are looking for people who have experience similar to the job.”

It’s a trend he doesn’t expect to see reversed. “Companies remain under tre-mendous pressure to contain expenses,” Gupta said. “People can argue whether that’s a good long-term policy or not, but in the short term we know that companies often do cut costs when it comes to having people in continuing education.”

That could change, given the ways that corporate hiring needs are changing.

“I think we’re at a point where companies are desperate to get new talent in; I hear that from employers all the time,” Suprenant said. “It’s all about how we attract and retain talent: Typically, we don’t just recruit from the metro area, but bring in people from around the country, and those grads tend to stay close to where they went to school because companies recruiting students here tend to be from this area. That’s one reason why employers say they wanted us to start the full-time MBA—they, too, are looking at it as a way to attract talent.”

One encouraging trend in the relationship between corporations and academic programs is the increasing value that companies are placing not just on technical skills, but innovative thinking.

“I think most employers value the basic experience and understanding the finance and operations and having a broader view” of business, Suprenant said. “The specialization we’re seeing more and more of, what I hear from employers is important to them, is entrepreneurship and innovation, even at the big companies like Sprint or Hallmark.

“A lot of people don’t think these big, traditional companies as entrepreneurial when they have thousands of employees, but most of their leaders are thinking today that if they’re going to stay in business, they need to be constantly innovating and seeing what’s on the horizon. They’re looking for people who are geared to that.”

Dan Falvey noted that a long-running item atop corporate wish lists is still deeply entrenched.

“Effective oral and written com-munications skills,” he said. “That’s probably more important today than it’s been in the past. We’ve put a huge emphasis on that in preparation of students for degree programs—I don’t want to say remedial, but fine-tuning, counseling, and coaching for students.”

And instead of academic rigor being measured in page-counts for class papers, the focus now is on conciseness, he said. “How concisely can you make the case for your critical thinking on your essay on corporate social responsibility,” he asked. “That’s No. 1, always.”