HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Let’s start with a history lesson: For someone living in Kansas City today, what’s the historical significance of the week of July 3-10, 1890? Take your time . . .

Give up? Over the span of that week, the Idaho and Wyoming territories were granted statehood, connecting the eastern half of the U.S. to existing states of Nevada, Oregon and California. For the first time, the nation was truly transcontinental. And that would be a very big deal for a fast-growing city in the Midwest, hundreds of miles east of those new states.

Now, let’s fast forward 125 years and ponder a business challenge. In it, you’re a logistics manager faced with a task: Your growing company has begun distributing products across every inch of those united states, and the organization’s long-term welfare is riding on your ability to get product from the warehouse to customers or consumers in no more than 72 hours. Only a new distribution model can meet that demand. You need a new facility.

Where to put it?

You can locate on either coast, but air-freight charges are going to eat you alive getting materials across the nation on your time frame. You can try smaller facilities in multiple, zoned locations, greatly increasing the logistical complexity of coordinating into and out of each region. Or …

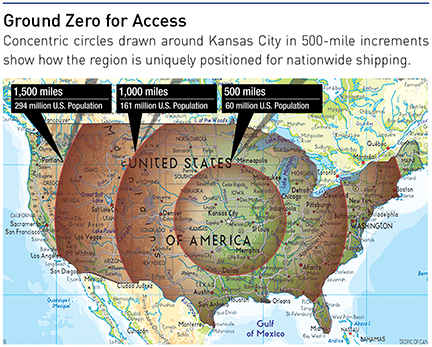

You can stick a pin in a map and draw concentric circles that show drive times in one-day increments: say 500 miles, 1,000 miles and 1,500 miles. To reach the greatest number of people in either direction—and almost everyone in America inside that farthest edge—where is the dead center of that first circle? Kansas City, America.

That may be just a thought experiment to you, but it’s the daily reality for a growing number of logistics executives nationwide who are making the move to this region precisely because consumer buying patterns demand faster, more efficient means of distribution. In the past five years, Kansas City has witnessed an explosion in industrial construction for warehousing and distribution, and the buildings aren’t just going up in size, they’re getting bigger. A lot bigger.

Not only that, they’re going up on a spec basis, without tenant commitments—and still, they’re filling up as fast as they can be completed.

Kansas City has always been a center of national commerce in some form, even before the nation went fully transcontinental in 1890. But in recent years, it has emerged as the go-to site for logistics expansion and modernization efforts at a time when that entire sector is undergoing profound changes.

The continuing rise of e-commerce, increases in outsourcing of transportation functions by U.S. businesses, nearshoring with businesses in Mexico, improvements in just-in-time supply chain management, advances in intermodal rail operations, along with new technology and the rise of Big Data—even a shortage of truck drivers nationwide—all are factors that work alone or in various combinations to foster new opportunities, executives say.

“With four interstates here now, we have access to all directions,” says Ken Hoffman, a transportation law specialist at Dysart Taylor Cotter McMonigle & Montemore. “Canada, the coasts, all the way to Mexico and the Gulf of Mexico—we’re perfectly located for e-commerce, which is already huge and the predictions are it will grow exponentially.”

The re-emergence of spec buildings is a welcome and important shift, Hoffman said, because “that was one of the issues identified just a few years back—people wanted to come here, but we didn’t have an inventory of ready-to-go space or projects that were already planned or approved and could be built out in short term.”

That’s changed with the advent of bigger facilities, he said, but there’s more to what’s going on than just square footage. “It’s clean, there’s not a pollution aspect to these operations, they put people to work in good jobs that pay well,” he said. “And with more e-commerce, we’re poised to continue with the growth of the logistics, warehousing and transportation industries around here.”

Changing consumer purchasing patterns have been a gut-punch to the big-box retail model, with increases in on-line buying cutting down on store traffic and slamming the door on new store construction. Worse, existing stores have been shuttered, with little demand from other retailers interested in taking over those spaces.

How bad is that getting? According to the real-estate tracing firm CoStar Group, the nation saw 325 million square feet of retail space open in 2006, the year before the Great Recession set in. In 2013, the fourth post-recession “recovery” year, that figure fell to 44 million square feet.

But while landlords panic and Alka-Seltzer is dropping at retail brokerage offices around the country, the folks down the hall in industrial are uncorking the Moët. According to Jones Lang LaSalle, more than 20 million square feet of industrial space has been added to the Kansas City market just since 2011—and virtually every square foot of it has been claimed.

“The Kansas City metro area is exploding with new bulk distribution Class A development,” said Dan Jensen of Kessinger/Hunter & Co. “Most of it is speculative, but there are also a few build-to-suits looking in the market and several underway.”

What’s happening in that space?

• Historically, the region’s absorption rate—net square footage filled after new vacancies are subtracted from new sales and leases—has run about 1.9 million square feet a year. In 2014, that ballooned to 4.4 million square feet, and in the second quarter of 2015 alone, nearly 1 million.

• In the past 2½ years, the market has seen 10.2 million square feet of new industrial development. That’s an annual rate of 2.26 million square feet, nearly 42 percent more than historic averages.

• A historic annual rate of 1.6 million square feet in new development is again on pace to roughly double, with 3 million more feet of space under construction at the start of 2015.

• And even with that new space coming to market, the historic vacancy rate of 7.1 percent fell to 6.1 by the end of 2014.

“We’ve reached a new level, and going forward, Kansas City is going to be more recognized as a key location for companies to use for their overall supply chain strategies,” says Whitney Kerr Jr., an industrial broker for the global commercial realty firm DTZ. “I think it’s going to continue to build on what’s already happened in the past few years, and it’s going to be huge for our area. I’m very optimistic.”

One reason for that optimism—an emotion generally shared by the brokerage community overall—is that just as suppliers to the Ford and GM plants drove industrial growth here over the past decade, online sales are creating tectonic shifts in the retail sector.

“These are trends changing the way we handle merchandize, and e-commerce is a huge, growing sector of the economy,” Kerr said. “What’s worked well for us is that e-commerce businesses have recognized that Kansas City is probably the very best location for them to operate. They can reach two-thirds to three-fourths of the country within two days, and the entire nation within three.”

That’s a huge differentiator for the region, he said, because for most products, overnight delivery isn’t an absolute essential—at least, not yet. “So with two-day shipping out of Kansas City, they can get virtually anywhere in the country,” Kerr said.

David Hinchman, an industrial brokerage specialist for CBRE, said what’s happening now should surprise no one. “It’s something we’ve been predicting, forecasting and recommending for years and years,” he said. That it hasn’t happened sooner, he said, was in part the result of recession and uneven recovery, and in part the challenge of getting the Kansas City industrial market aligned with changing industrial needs.

“With the whole decision-making process that corporations have to go through when they need space, when they’re finally ready, you have to have it ready for them, and most will have lost time if you have to build to suit,” Hinchman said. “Kansas City is finally in that position where we have the product in various sizes.” A lot of that activity, he said, had involved the mega-buildings of up to 800,000 square feet, or more, but the middle market of 30,000 to 80,000 square feet has been active, as well.

Rather than putting pressure on rents by infusing millions of new square feet into the market, Jensen said, the recent wave of new construction in general had pushed rents up, “which it turn is pulling rents up for Class B as well,” he said. “However, there are certain aspects of the market, primarily the large big box market, that are getting very competitive with rates, and they’re even going down a bit because supply is pushing ahead of demand.”

That’s just one challenge facing landlords and investors, brokers say.

“We’ve seen lease rates in Class B and older Class A that have been flat to declining,” said Kerr. “The problem we deal with in some of the B and low-A sites is that once they lose that tax abatement, once it burns off, then you’ve got a situation where these new buildings, with the incentives in place, become very competitive, so in order for the B/A to compete, they have to drop their rates.”

That’s one reason he believes the area will continue to see new construction. “There will always be a place for the older buildings,” Kerr said, “but they’re going to have to discount price if demand is not able to keep pace with the supply of new space, but in the last 12 months, we’ve had positive absorption of more than 5 million square feet. That’s new territory for our market—we’ve never seen that kind of growth before.”

For a regional economy already defined by its diversity, the logistics explosion is paying off for more than car makers and e-commerce fulfillment sites: It’s strengthening Kansas City’s position with companies that do business internationally.

Al Figuly has some of the stats. He’s president and CEO of the Kansas City Foreign Trade Zone, “and of about 177 or 178 active FTZs in the U.S. and it’s territories, we rank in the top 25 in terms of value of overall FTZ activity,” he says. “We’re ranked 22nd for importing goods that go into production and are exported, so we do a lot of value-added work in terms of manufacturing and processing. We rank very, very high.”

With more than $2 billion in goods shipped in and out of the region last year, “we do more than St. Louis, Denver and many of the major areas, and we’re nipping at the heels of Chicago.”

Over the past dozen years, he said, the average growth rate in FTZ activity was near 19 percent, reinforcing Kansas City’s historical position as a center for commercial trade. “Our history is that of a trade center,” he said. “It’s not a new concept. We’re blessed by good geography and good infrastructure but it’s very, very important that we continue to keep up with our infrastructure funding” in both Missouri and Kansas.

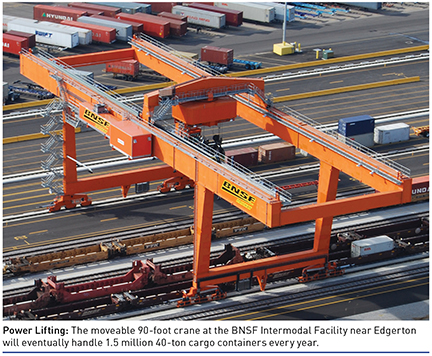

Another side effect of recent growth: New academic programs that train a new kind of logistics worker. Johnson County Community College has seized on the emergence of Kansas City Logistics Park to collaborate with BNSF, NorthPoint Development, the City of Edgerton, the Workforce Partnership, and the Southwest Johnson County Economic Development Corporation to set up classes that will yield workers certified in supply-chain management, lean operations, inventory management and enterprise resource planning, as well as forklift certification, handling of hazardous wastes and OSHA regulations, among others.

“We are going to educate their current employees as well as educate the public in some of these skills so they can be more marketable to apply for and get jobs in these open positions,” said Debbie Rulo of the college’s continuing education office.

Karen Martley, JCCC’s vice president for continuing education and organizational development, said the pieces were coming together for a work-force segment that will be more highly valued, better-compensated and more attractive to young workers.

“From the work we’ve done all over the Kansas City area, we think there’s a work force here that is not drawing from just one area, and for them, it really does start with education. With the whole supply chain concept, we’re spending time at the high-school level to reach students, and their parents, too, as well as counselors,” Martley said. “There’s a work force here that can be reskilled or take minimal tooling to make that happen if we can get people to understand the opportunities with these new career paths.”

Carl Wasinger, CEO of Smart Warehousing, said the 13-year-old company moved into the logistics park in October to consolidate other operations in the region and create additional efficiencies. The company operates in 11 states, with affiliates in Canada and Europe, providing space and technology that customizes warehousing solutions for clients.

A self-described “western Kansas farm boy,” Wasinger recalls the guidance of a professor from Georgia Tech who counseled his logistics-class students that “there’s a good reason the heart is in the middle of the body.”

Kansas City, Wasinger said, wasn’t on the logistics radar for many years as companies looked to Chicago, Memphis, Dallas and other areas viewed as strategically positioned. “But geography will always win out,” he said. “It’s fundamental to logistics and the supply chain. As the infrastructure continues to expand, and as the e-commerce world continues to evolve and mature, Kansas City is more the kind of location they’ll pick. We didn’t always have the right balance of carriers and infrastructure to get products in and out, but that’s been changing and will continue to drive a pretty robust supply chain/logistics sector in Kansas City.”

With more industrial buildings coming on-line, and more of them in the mega category, what’s the outlook for the way industrial space is designed? Can these behemoths become even bigger?

“That’s been a debate for a number of years,” said Hinchman. “Once you get past a million square feet, it gets tough to remain efficient for many reasons. We’ve sent the sweet spot for Kansas City in the 250,000-to-500,000 range, and larger than that of late. I’ve got to believe in the next year or two, we’ll see a 1-million square-footer plugged into this market. Somebody’s going to do it.”

And more broadly, how big can this overall trend get for the region?

The auto-parts growth isn’t over yet, and brokers agree with Kerr when he says, “e-commerce is the next big wave. We’re really well-positioned to take advantage of that. The other thing is that we’ll continue to be good for food-related and ag-related operations—we’ve always had that, but I think you’ll start to see more of that with more businesses related to that locating here to take advantage of that.”

“The capacity, said Figuly, “is unlimited. The only limitations are the extent to which we continue to maintain and promote the development of infrastructure; highway transportation is very, very critical. The fact that seven or eight Class I railways are here speaks to the value that transportation has to our imports and exports. We have a real opportunity here as a community.”

Overall, Figuly said, “I’m very optimistic about the future.”

Back in the early 1990s, when Dave and Demi Kiersznowski launched DEMDACO as a national distributor of gifts and home décor with inspirational themes, Kansas City’s centrality might have been a great reason to base their operations here.

The truth, said Dave Kiersznowski, the company’s CEO, is somewhat more prosaic: “We lived here.” But if you’re going to ship product in from overseas and back out to customers anywhere, there are distinct advantages to being in this market, he said. Demdaco was the first tenant to occupy space in the sprawling Logistics Park Kansas City near Edgerton—more than 326,000 square feet of space. The move has paid off in a number of ways.

“Kansas City is smack in the middle of the country, and that means you’re going to have greater efficiency with your shipping costs,” says Steve Fowler, the company’s chief operating officer, and the man Kiersznowski credits with much of the its success. “The demographics of our customers suggest we might be better off being located further east, but there are tradeoffs with that.”

As students of the science behind logistics, he and Kiersznowski can tell you that with the smaller square footage DEMDACO has after moving from a North Kansas City site, operating costs have plummeted, but capacity has improved. Simply put, if you stack pallets six high instead of four high, you’ve cut your footprint by a third.

“A lot of the big cost is linear feet that forklifts have to travel; the wider you go, the more bays you have to service,” Kiersznowski said. “And our drayage costs have gone to zero,” he said, referring to the charges for getting materials to and from the point of shipping.

“These are small things that companies don’t often think about, like the high costs of containers. Those costs are set by other things that people are bringing into this market, and what they’re bringing in is very beneficial for us; it creates a competitive rate system. The international trade ecosystem here is something you’ll not find in every city.”

Neither is the creative ecosystem, something that helps an arts-related business thrive in the town where Hallmark, as a globally known company, has created a gifting-business culture and infrastructure, Kiersznowski said.

“Were I to think through starting a gift company, Kansas City would be Main and Central on my radar” for those reasons, he said. “There’s an infrastructure for the channels and distribution, and it’s easy to find the talent. It’s a wonderful place to have a gift company, and our clients, wherever they are in the U.S., know that we’re not seven UPS zones away.”