HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

The return of near-zero interest rates has many investors flocking to equities markets. For those with shorter time horizons, that could pose a problem.

Remember TINA? She was that alluring goddess of double-digit investment returns for much of the past decade. Near-zero interest rates for much of that time had investors scrambling for other ways to find yield, and with stocks, TINA—There Is No Alternative—was there for them.

That is, until the big correction of late 2018, when the markets gave up nearly all of that year’s gains after annualized returns topping 13 percent in the wake of the Great Recession. As the U.S. and other countries began to take its foot off the interest-rate brakes in late 2015, elevating them from 0.25 percent level they’d held for seven years, investors were able to breathe a bit and reconsider instruments that might prove less risky. For some, the post-COVID world and the Fed’s response to it—slashing rates back to 0.25 percent on March 16—TINA is back.

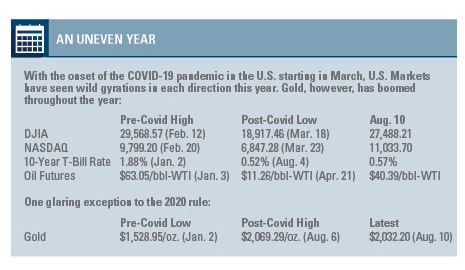

And the more an investor’s portfolio has been disrupted by COVID-inspired market gyrations, the more likely that person is to think that she’s looking pretty good these days. After all, while bond yields have plummeted, the Dow has shaken loose of its fear-driven sellout from late winter, recovering to within 6 percent of the all-time high set Feb. 12, while the NASDAQ has itself set new highs.

TINA’s back, right? Depends on whom you ask, and on who’s investing.

“As rates came lower and lower, many investors, especially, those seeking yield, many times your retired population, are forced to move out of income-oriented investments like bonds, money-market funds and CDs, and into higher-yield stocks,” says KC Mathews of UMB Bank. “That worked out fine over the last three or four years. Then came the big drop after COVID, but if you think about it, year-to-date we’re up 1 percent total rate of return. It’s kind of like, ‘OK, what happened with COVID? IT hasn’t changed retirement planning or the results for a lot of people.”

Unless those investors panic-sold at the first signs of the big decline in March.

Unless those investors panic-sold at the first signs of the big decline in March.

For those who pulled out of equities and didn’t get back in quickly, they missed one of the biggest stock-market rallies in one of the shortest recovery periods on record. Anyone flirting with retirement, or already in retirement and counting on that pre-COVID portfolio to sustain their spending habits, is now facing some agonizing reappraisal, wealth managers say.

“Those groups that are already retired or, more importantly, those about to, psychologically felt the brunt of the pain caused by COVID,” says Justin Richter of Mariner Wealth Advisors. “While retirees relying on their portfolio of investments, or now about to, the big thing is they

are now more dependent on income flow. That cash flow takes a hit as interest rates stay lower longer. Now they’re near all-time lows, and many companies as part of this have suspended or cut their dividends, and that also eats into cash flow.”

March brought, for many, a classic example of why it may be a good idea to stand fast in the face of a sharp market correction.

Often, when there is a panic nature of a market selloff, sometimes that causes investors to over-react and sell at precisely the wrong time,” Richter said. “Those intentions are hard to control when working with finite capital. If that happens at the wrong time and the recovery is missed, the retirement plans have to be materially altered in order to adjust for those.”

The challenge for many investors in this climate, says Commerce Trust Co.’s Scott Boswell, is to get their minds adjusted to that risk, as well as their portfolios.

“Certainly, everybody hoped this would be a V-shaped recovery,” Boswell said. “It probably doesn’t look like a V at this point, there’s still a lot of hope for more of a U-shaped one, but what everybody wants to avoid is a W—back up, then down again. With the still fair amount of uncertainty, has COVID been a non-event for investors? No, not at all. Is it going to be a long-term systemic issue for many companies.”

The key, he said, and a cue investors might want to be paying attention to, is progress on either a vaccine or a technology that keeps this virus—and the next—from running rampant. In the meantime, though, investors must recognize that “safe options are gone in the near-term,” Boswell said. “With zero-interest rates out for two or three years, the idea that you’re going to be able to make any sort of return without taking risks is a non-event.”

The real issue for investors, these executives say, is whether they had the right asset allocation going in last spring. This may not be the best time to reallocate, because changes to that portfolio design based on short-term movements rarely produce the desired returns.

What we’re seeing now, advisers say, is somewhat unusual: surging equities markets in the face of a global recession. “Given this divergent path of the overall economy and capital markets, along with the shock of the volatility in the first half of this year, I think both retirees and those about to retire are taking a step back and reassessing what may have been their retirement plans,” says Way-ne Park of American Century Investments.

“We’ve observed our clients taking different approaches,” Park said. “For many, they held steady through the volatility while for some, we saw big swings to and from money-market funds—presumably, nseeking safety in the near term. But across the board, we’ve observed higher engagement, seeking information and guidance from our financial consultants to help with their investing decisions.”

Life Near Zero

Low interest rates, says Tom Siomades, chief investment officer for AE Wealth, often impact the pre-retiree and retiree the most. The Fed’s move to cut rates, he said, “is often made to infuse money into the economy, not to support savings and investments. So, for the investor who is in or nearing retirement, this could mean they are working harder to seek returns to maintain their lifestyle in retirement.”

Too often, he said, “little is done by way of evaluating risk and, so long as things keep going as they have been, these investors are happy, and they often discount the downside until it’s too late. The risks are they get little yield from CDs, money markets or Treasuries, so they have to go to the stock market to grow and maintain their lifestyles.”

With current rates pushing people into riskier assets like equities, Siomades said, “the hard truth is people need to understand that increasing their risk will impact their investments both to the upside and downside. If they are uncomfortable with that, they need to change their expectations in retirement, and they need to get advice from a financial adviser.”

Lower rates, said Mathews, are the result of what he calls a 40-year project in managing the nation’s fiscal policy. “In 1981, the 10-year Treasury was just above 15 percent,” he says. “Over the next 40 years, it’s almost a straight line to virtually zero. That is the underlying issue on impact with retired folks.”

Lower rates, said Mathews, are the result of what he calls a 40-year project in managing the nation’s fiscal policy. “In 1981, the 10-year Treasury was just above 15 percent,” he says. “Over the next 40 years, it’s almost a straight line to virtually zero. That is the underlying issue on impact with retired folks.”

Throughout that decline, when investors had to accept a 6 percent return after an 8 percent bond came due, they still had significant cash flow. “At 50 basis points for the 10-year, the cash flow starts to evaporate,” Mathews said. “That’s more about a slowing economy, and low inflation in this environment. I don’t believe COVID changes retirement planning—it was nothing more than wake-up call.”

Boswell says investors will do well to understand that instruments like bonds won’t be there for significant income, and for at least a couple of years.

“The Fed has basically said we’ll be at zero through 2022,” he said. “What that tells you is that you’re going to have a negative inflation-adjusted return” even if inflation remains low. “There is going to be some inflation, and the amount of cash pumped in by the Fed could dictate that.”

At least in the foreseeable future, Richter said, “I doubt we’ll see negative interest rates—they can’t collapse much further. That definitely causes cash-flow planning to be more challenging. It’s a trade-off between trying to maintain a similar level of expectations while having to increase your risk exposure to do so. Or maintaining a risk-neutral position with the idea of generating less income.”

That dynamic, says Park, will compel investors to rethink strategies if they have yet to retire: Work longer and defer retirement, or spend less and save more.

The first option, he said, “will keep income from their work coming in without having to rely on their nest egg. Unfortunately, in the current environment, this is not a choice: Many have lost their jobs as evidenced by the high unemployment rate in second quarter and health concerns with COVID-19. Being in higher risk groups, some may not want to take the health risk to continue to work if their jobs require frequent contact with other people.”

Alternatively, Park said, they can close the gap “by spending less on discretionary things like vacation. Given the pandemic, perhaps settle for a lower cost ‘staycation’ as a win-win.”

For those who have already crossed over the retirement threshold, the first concern is defending income streams and cash flow, wealth managers say. They may find some relief in higher yield in alternatives, such as short-term fixed-income products, convertible bonds or preferred stocks with higher and reliable dividend payments.

But again, as Park noted, “these come with risk of some loss over the short term.”

Seeking Yield

So where, in this climate, do investors turn to secure yield without taking on crushing levels of risk? “We’re definitely challenged with that, and it’s causing us to be more creative,” Richter said.

“There are certain opportunities still with dividend-paying stocks, but they have to have some level of COVID resistance. You’re looking for balance sheets that continue to raise dividends. You have to deal with some price fluctuation, but as long as there’s a strong balance sheet, they’re not forced to cut dividends. In addition, it’s possible to combine options-writing along with equities to generate additional income. But with options come additional risk and complexity.”

Many people, wealth managers say, are exploring real estate, which has produced some solid returns in targeted residential and industrial opportunities, but significantly less with retail and office space in the post-COVID world.

“I think one of the impacts that has not been talked about enough related to the cash from the Fed and the multiple stimulus bills to help the economy is the potential long-term effect, more specifically on what investor expectations of taxes should be in the future,” said Park. “At all levels of government—federal, state and local—they are facing a perfect storm of lost revenues, higher expenditures and higher debt payment.

There are really only a couple of ways to get past this storm, he said: “Either provide less government services or collect higher tax revenues. Both will probably need to happen, which means investors should expect higher tax rates in the future.

This, along with the low-yield environment, should be two inputs to think about as they review their portfolio. And they also should increase considerations for municipal securities and other tax-efficient investments in the future.

Longer Horizons

For those in the Gen-X set or the Millennials who have followed them into the investor class, the economic whiplash of the past decade is changing the calculus on retirement. Gen-Xers, in particular, have now witnessed in a span of 120 months the Great Recession, up to that point the biggest economic downturn since the 1930s, and the COVID downturn.

Both generations have seen the Boomers, many of them being their parents, lose significant assets in each downturn, and on top of that, witnessed the stunning fall of home values during the Great Recession. Given that a paid-off home is often the largest single asset within a family, it was a double-whammy that continues to shape attitudes of younger investors. As a group, they have been more reluctant to get into homes because they simply didn’t see the long-term value proposition.

A bigger concern, wealth managers say, is that those with the longest time horizons to retirement are avoiding the kind of risk that historically has worked in favor of investors, especially with the stock markets.

It’s tough to look across entire generations and assess where the risks and opportunities might lie, given the economic diversity within each. As Park noted, “each person’s situation and appetite for losses is unique, so it’s a good time to review their portfolio, outlook on expectations, family needs/wants and a hard self-reflection on how much volatility and risk they want to take on with a critical focus on what cash needs they may have in the next one to two years.”

“I am not encouraged by the Gen-X generation’s ability to grow more optimistic as we progress because of the economic turmoil they have seen in their lives,” said Siomades. “This may be a mini-version of the Depression-era generation that was much more risk-averse than generations that came of age during periods of prolonged economic prosperity.”

He cited a recent study that said Gen-Xers and Millennials were cutting back on day-to-day household expenses by 75-80 percent as a result of the pandemic, and that nearly 17 percent of Gen-Xers had cut back on their IRA contributions, with more expected. And Millennials, he said, aren’t much different. “Gen-X have seen their parents (Baby Boomers) struggle; they often saw them through strong economies as well and have a perspective. Millennials have mostly seen their parents struggle, so are more apt to save and take a less optimistic view, which may account for the high percentage who continue to invest for the long haul.”

Living Longer

One aspect of wealth management that has changed over the past two generations has been the increasing life span of clients. Anyone who had made it to 65 today can expect to live for another 20 years—slightly more for women.

Given that, should risk play a reduced role in retirement planning among Boomers, given the time horizons involved? Not necessarily, wealth managers say.

“It really depends on where that person is at retirement,” said Boswell. “We do a lot of financial planning, do the Monte Carlo analysis, say here are your goals and objectives, what it will cost you, what you’ll retire with. You take on more risk during accumulation, then take that risk off as you save through retirement. It’s a question of does living longer means you get to retirement with more or take more risk through retirement to maintain.

“If you’re comfortable taking risk during your retirement years, and you may need to be without enough of a nest egg, then maintaining through retirement is going to be even more challenging over the next couple of years,” Boswell said.

That, wealth managers say, is where volatility can hurt people, even those with time horizons of 25 years or more. Regardless, Boswell said, every client “still needs enough balance in their portfolio so that when they need the money, it’s there to spend.”