HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

March 2021

The Kansas City region has long had a reputation for a competitive banking market, and statistics support arguments that as a metro area, we are, in fact, overbanked.

The Kansas City region has long had a reputation for a competitive banking market, and statistics support arguments that as a metro area, we are, in fact, overbanked.

There are multiple reasons for that, but the historical record has, in part, been rewritten over the past five years. Macro trends in the banking sector have conspired to reduce the number of banking organizations between Topeka and Sedalia, from 112 in 2015 to 85 operating today.

But it would be a big mistake, banking executives say, to think that the market is somehow less competitive just because fewer players are on the field. Why?

“We now have more national bank players than we had in 2014, and other banks have begun to expand their presence in the market,” says Bill Ferguson, president and CEO of Central Bank of the Midwest. “Kansas City has also begun to see credit unions expand outside of their original scope without the tax burden and fintechs continue to challenge our core lending and payments business.”

There’s an upside to that, he said: “Our local businesses and consumers are the recipients of better banking deals and products as a result of this healthy competition.”

The consolidation we’ve seen in this market has been going on for a long time. A generation ago, that same geographic footprint had a whopping 157 institutions, nearly twice as many as today. Almost all of the ones no longer with us were acquired by larger banks; in some cases, failed banks were acquired by out-of-market institutions. In most cases, though, the smaller banks were succumbing to megatrends that their executives had pointed to as existential threats—chief among them, soaring costs of regulatory compliance. But the ability to finance new service lines and products played a role, as well.

Still, a market with 85 rival brands has plenty of competitive froth, says Kevin Barth, chairman and CEO for Commerce Bank. And again, there are reasons for that.

“Even though there may be fewer banks, certainly, a number of new competitors have come in and built new branches or opened new facilities,” Barth said. “The Midwestern markets on commercial have some of the lowest loan rates in the U.S., and it’s because Kansas City—and St. Louis and some other Midwestern markets—are so competitive. We still have high numbers operating here.”

For the broader business community, that’s all good news. “It’s a very good market from borrower and customer standpoint in general,” Barth said. “It’s a little unique in that we have two very significant regional banks headquartered here. That’s very unusual. A lot of major cities don’t have even one bank headquartered there.”

He was referencing his bank and UMB Bank, which have led this market in terms of assets and deposit market share for years. For most of the past generation, Commerce was No. 1 in those metrics, but UMB overtook it in 2019 with a surge in assets. And in 2020, they were so evenly matched that, to use the metrics of a political election, UMB prevailed by a margin of less than one-fourth of 1 percent of their combined assets: 50.12 to 49.88 percent.

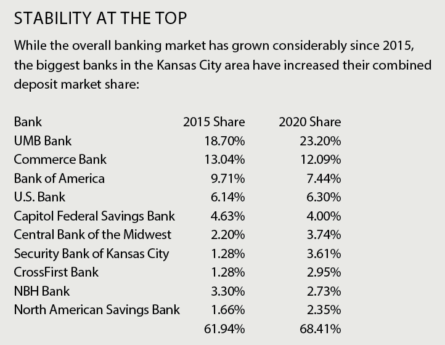

Those two banks had some impressive company at the top. Among the 10 largest banks in the market, the combined overall deposit share rose from 62 percent in 2014 to 69 percent in 2020. Much of that increase could be attributed to a strong showing by UMB, whose chief executive, Jim Rine, says there’s little for bank customers to fear from that trend.

“I don’t view that as a negative for business owners,” Rine said. “We have a competitive banking market here and numerous strong banks that are ready to serve our community. Business owners have good options in our city. And, after 108 years of operation here, we know the business community and how to serve their needs better than anyone.”

What changed most over the past five years, in the broadest sense, is what changed over the past year: the organizational pivoting that took place with the COVID-19 pandemic wrecking retail sites across the nation. Turns out, though, that such change wasn’t all bad.

“The challenges of 2020 allowed us to solidify relationships with existing customers and created opportunities to build new relationships,” said Ferguson. “We remained available to our customers in person throughout the crisis and found new ways to engage remotely to take care of our customers, employees and the community.”

It also forced Central, he says, “to rethink the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of many of our processes in search of accommodations and efficiencies to continue meeting customer needs as disruptions persisted.” That meant finding new and different ways to communicate, prospect, close, and retain business, he said.

Clearly, said Rine, this is a time when banking relationships matter. “Relationships are essential to the way we do business,” he said, “and we leaned into that even more during the past year to ensure our clients and customers felt that partnership as they navigated uncharted territory.

Clearly, said Rine, this is a time when banking relationships matter. “Relationships are essential to the way we do business,” he said, “and we leaned into that even more during the past year to ensure our clients and customers felt that partnership as they navigated uncharted territory.

“For many reasons, this has been one of the most challenging years in history. We have worked tirelessly, including nearly 24 hours a day during the peak of PPP, to make sure our customers, our associates and the communities we serve are receiving what they need from us.”

The challenge was more than just an organizational one. At the leadership level, it was a little more personal.

Said Barth: “What we were forced to do, and how we were forced to do it, did two things for me: One, a lot of the investment we made in tech and connectivity—before, I didn’t always understand the need at the desktop level. But it was all worth it; it really allowed us to maintain strong connectivity between employees at the bank, employees and customers, even with 85 percent of us working from home.

“The other thing I was grateful for was, the institutional knowledge and the culture we have that led to the resilience we needed to pull together in difficult times.”

With the possible exception of the financial panic that triggered the Great Depression, the ability of banks to move quickly in new directions has never been more evident, or more successful, banking executives say. And they uniformly point to one example of how that response met a critical need as cities and states began imposing operating restrictions on businesses: The Paycheck Protection Program outcomes.

“The year actually represented a lot of opportunity for those engaged and ready to act,” said Ferguson. “PPP, in particular, has been challenging with the constant evolution of the inception, funding, and forgiveness of the program. It has been rewarding to be part of meeting the needs of so many employers and their employees.” Central was able to come through in the clutch for new and existing clients as part of the ongoing process, he said, closing over 3,200 PPP loans for more than $330 million— many of which served their purpose and have already been forgiven, he said.

PPP, said Barth, represented “a flood of work. But even with 85 percent of our people working from home, we were able to make about 10,000 loans and get $1.8 billion of capital out to our customers for them to get into the pockets of employees and keep the economy going.”

He’s particularly proud that no one who needed the help was shut out of the process. “We didn’t leave one customer at the gate when the PPP money ran out,” Barth said. “And while a lot of the large national banks were closing down applications for PPP 2.0, we’re still going to keep ours open as long as we possibly can. But it’s been hard.”

At UMB, said Rine, 1,600 PPP loans put $285 million in to regional business.

“For many reasons, this has been one of the most challenging years in history,” he said. “We have worked tirelessly, including nearly 24 hours a day during the peak of PPP, to make sure our customers, our associates and the communities we serve are receiving what they need from us.”

UMB has received approximately 2,300 PPP applications for a total of approximately $400 million. To date we have funded 1,600 loans for approximately $285 million.

As it turned out, 2020 was a pretty good year for regional banks. The trend line of increasing net income continued; by year’s end, aggregate net income for those 85 banks was up $1 billion over 2014 levels, and increase of nearly 85 percent, the FDIC data show.

“The health of the regional banks in general is very good,” Barth said. “Many of the loan losses we feared would occur in 2020 did not materialize, partially because of some of the economic relief measures like PPP and other things.”

But regulators gave banks an uncharacteristic amount of leeway to make things work, he said.

“Regulators know that with a lot of companies hurt most in 2020, what they needed as much as anything was time. Regulators allowed banks to show customers some grace until things could start getting back to normal.”