HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Willie Lawrence lays it all out there for the small business owner and the corporate executive alike:

“Executives and leaders with highly charged careers can tend to overwork, not sleep well, and cope with stress with unhealthy eating habits like consuming too much alcohol, remaining sedentary, or smoking—all poor choices that can lead to hypertension,” says Lawrence, chief of cardiology at Research Medical Center.

Like obesity, and often related to it, hypertension is a gateway disease that may not kill you by itself, but certainly creates the conditions that will. It’s a direct link to heart disease and stroke, the No. 1 and No. 4 causes of death in the United States, Lawrence says.

And it’s an incredibly pervasive illness.

“This is a disease that affects more than a few people,” says Tracy Stevens, medical director for the Women’s Cardiac Center at Saint Luke’s Hospital. “Studies show greater than 90 percent of people will have high blood pressure in their lifetime, and the corporate world is certainly at a far greater risk.”

Despite the threat, fewer than half of Americans with hypertension are even aware they have it—hence its nickname, The Silent Killer. And of those who have been diagnosed with hypertension, many don’t have it under control.

“It is truly a silent disease,” said Kamal Gupta, director of the Complex Hypertension Center at the University of Kansas Hospital. “The problem with business executives is that you’re often not affected by it day to day; you keep ignoring it and move on. But there’s a huge cost to society, billions of dollars’ worth a year in wasted productivity because of headaches, hospitalization, stroke or heart failure.”

And lifestyle, Gupta says, plays an important role for busy executives.

“They travel, they don’t eat right, they don’t exercise enough and they eat out, so salt is a big deal,” he said. “In restaurants or on a plane, the food is rich in salt. The average American eats five times the recommended salt, and busy executives probably eat a lot more.”

Long hours and sleep loss go hand in hand as contributing risk factors, he said. “Sleep brings that average reading down for most of us; we’re nocturnal dippers, with drops of 10-15 percentage points, but that’s less so in hypertensives. If their sleep is erratic, if they’re traveling through different time zones, if they don’t have the REM sleep, then they don’t have the nocturnal dip in their blood pressure, and their average readings are higher than if they’d had a good night’s sleep.”

We’ve all heard of hypertension, but what is it, really? Basically, it’s excessive force pushing blood against the walls of vessels and arteries. If you have it, your heart is working harder to pump blood, and that strain hardens the walls of your arteries and vessels (a condition called atherosclerosis), and it contributes to kidney disease as well as stroke and heart failure.

Among the challenges in getting people to understand their own level of risk are the multiple factors that influence it. The systolic/diastolic pressure readings (reflecting pressure as the heart pumps, then as it relaxes between beats), are generally thought to have a “normal” range below 120 over 80. Pre-hypertension is defined as the range from 120-139 over 80-89.

Stage 1 high blood pressure measures 140-159 over 90-99, and Stage 2 is greater than 160 over 100 and above.

Part of the challenge of controlling hypertension in the population are the roles of age, gender and race. You can go from Stage 1 to Stage 2 just by lighting the candles on that 60th birthday cake, because at that age, high blood pressure is defined by readings higher than 150/90.

Race is another factor; as Lawrence notes, “African-Americans are disproportionately affected, with the highest rates of hypertension in the world.” Among non-Hispanic blacks age 20 and older, he says, 43 percent of men and 47 percent of women have high blood pressure, compared with 30 percent and 27 percent of white men and women. And blacks have a risk of first-ever stroke that is almost twice that of whites.

Another challenge is determining the source of hypertension; its causes cannot be determined in as many as 95 percent of diagnoses. But we do know what contributes to it. Among those are behavioral issues, like smoking, being overweight, sedentary lifestyles, too much dietary salt and stress.

Then there are factors outside our control, such as genetics—if either of your parents or grandparents had hypertension, keep a close eye on your own readings. Aging is another factor, as are medical conditions including chronic kidney disease, adrenal and thyroid disorders and sleep apnea.

A final factor is gender. Hypertension comes closest to being a gender-neutral malady for people in the 45-65 age range. But for those not yet in the mid-40s, it’s a significantly greater risk to men, and for those over 65, women are disproportionately affected.

That’s a dynamic that has Stevens’ attention at Saint Luke’s.

“The most common reason Americans are admitted to hospitals is congestive heart failure, and it’s more women than men,” she said. That’s of concern in the business world, she said, because “studies suggest that, with the same level of stress in a corporate environment, the impact on cardiovascular health in women is more pronounced. We’re appreciating this now as more women are in these positions.”

Of course, the risk extends well beyond C-suites.

“It’s a scary thing, but 2015 is the first time in history where the majority of women are post-menopausal,” Stevens says. The hormonal changes of that process in women release nitric oxide, which dilates blood vessels, which controls blood pressure. And because the diameter of blood vessels tends to be less in women than in men, she said, it contributes to a higher prevalence of stroke and heart attack in corporate women than in their male peers.

For a nation in the throes of a health-care finance crisis, America seems to be unusually complacent about high blood pressure, its risks and its costs. Consider:

• Roughly 70 million adults—29% of the population—have high blood pressure. That’s nearly one person in three.

• And among those, nearly half (48 percent) do not have their high blood pressure under control.

• Among the rest of the population, nearly half has pre-hypertension. That’s another one in three.

All told, says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, high blood pressure costs the nation $46 billion each year when you factor in the cost of health-care services, medications, missed days of work and other lost productivity, and other factors.

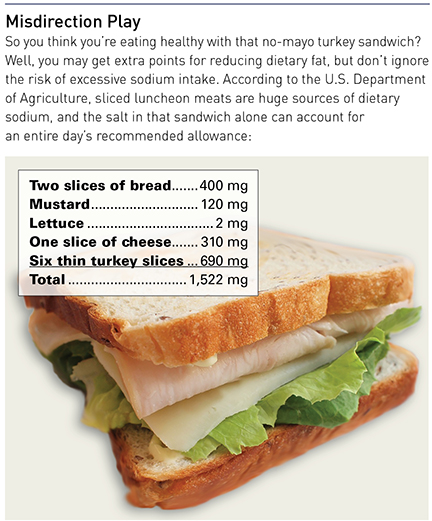

According to CDC estimates, the U.S. would see a reduction of $18 billion in that health-care expense every year, and 11 million fewer cases of hypertension, if people would cut their salt intake from an average of 3,400 milligrams a day to 2,300 mg per day.

But if we’re to take this seriously, Stevens says, it’s also imperative that people get their blood pressure checked at least once a month. And if that reading is above 140/90, check it the next week. If it stays there through a third and fourth reading, talk with your health-care provider.

Simple as it sounds, that approach has the potential for reducing costs, “but at the same time, we’re not seeing the individual consumer stepping up to the plate,” she said. From a corporate wellness vantage point, “companies know they need to reduce their health-care costs, and see this as a powerful way to help employees control their blood pressure and reduce costs. We’re making headway, but when it comes to the consumer, how much ownership are they willing to take?”

For someone on the road a lot, or someone logging a lot of hours at the office, Gupta advises people to take action and find out where their blood pressure is—not just with a single reading or check-up, but by frequent monitoring that can provide a clearer picture of one’s readings and risk.

“The one good thing about hypertension,” Gupta said, “is that it’s very easy to treat. Once you know you have high blood pressure, you now have the tools to check it at home. We encourage people to keep a device at home to check theirs, or to use it in the workplace, and if the reading is high, see your doctor and take your medications.”

Time-starved executives may make the wrong cost/benefit analysis when assessing the potential rewards from dedicating part of a day to a doctor’s office visit, but if that’s the basis for their decision, they’re using the wrong calculus, professionals say.

“For the busy person, you don’t have to go to the doctor’s office these days,” Gupta said. “We work through e-mail or electronic communication, and that may be the best advance we’ve see in managing hypertension. We have all electronic records and have ways to communicate with physicians and nurses electronically. All a person has to do is check their pressure, keep a log, and send it to the provider, who will look at it and respond. We don’t see patients more than one time every six months, on average, but we can keep in touch more frequently with electronic means.”

Lawrence cites the impact of lifestyle changes on disease management.

“If you’re borderline, do something: Aggressive lifestyle modifications—the earlier, the better—are the most effective approach to high blood pressure control,” he said. And if you’ve been diagnosed, take your medicine—the failure to follow through on prescription dosages and time intervals is a huge factor.

Beyond those, he said, “restrict sodium to less than 1,500 mg a day. Once you are without it for several weeks, you won’t miss it. It’s replaced with a newfound appreciation for food, and makes you go out and find other herbs and seasonings with which to cook.” Focus on the things you can eat, he said, such as good quality meat, fruit and vegetables. “Control when you eat and what you eat.”

Stevens concurred: “I think of foods as medicine,” she said. “What we’re eating now is not what the body needs, it’s what we want. And that’s a big disconnect, especially with blood pressure. I’d love to see every airport with walking trails, not just places to go to eat that Cinnabon.”

And get serious about building more exercise into your schedule, the first step to placing the burden for hypertension management where it belongs.

“If we could ask Americans to take ownership of one thing, it would be blood pressure,” Stevens says. “It truly is the most neglected disease in the country, and from a corporate standpoint, it’s one of the top five employer health expenses. And for the lifestyle of the executive, here at Saint Luke’s with our program, we’re very, very concerned with that population. A lot of this is lifestyle, and if we can be disciplined, even without blood-pressure medicines, we can truly make a difference.

“But it all comes down to discipline,” she said. “The ownership for this has to transfer from the health-care provider to the patient.”