HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Penn State. Florida. North Carolina. Indiana. It reads like the line-up of schools you’d see while perusing Saturday’s college football scores. It’s also a sampling from the top on-line MBA programs ranked this year by U.S. News & World Report. More than that, it’s a roster that reflects the fierce competition that Midwestern colleges and universities are engaged with in the current on-line learning environment.

Winning the in-state recruiting battle for academic talent has always been a priority for colleges and universities in the region, and the drive to highly qualified applicants from out of state certainly predated the Internet. But for graduate-school program administrators, there’s a new level of competition with the ability of large, tax-funded universities now able to project their marketing messages to prospective students in this region.

The flip side, of course, is that local institutions can play that game, as well, and access inquiring minds all over the world. And now, with the well-documented challenges facing for-profit higher education, new opportunities are emerging that will continue to pit universities in Missouri and Kansas against big-name institutions from anywhere in the country.

One of the most highly visible and successful of the for-profits, the University of Phoenix, is reeling from multiple investigations being conducted by the federal justice and education departments. Just last month, the Department of Defense got in on the act by giving UP, in effect, the military boot from defense installations, whose personnel account for roughly 10,000 of the 200,000 students enrolled at the on-line school. The damage being done to its reputation could further shrink enrollment there.

“All of us in non-profit higher education are happy to see the world figuring out the problems with for-profit higher education,” said Holden Thorp, provost for Washington University in St. Louis. He called the Phoenix case “a watershed moment.” “What most of us consider to be predatory practices in terms of lending and degrees they’re marketing are becoming exposed,” he said. “And that’s a good thing, because a lot of people are being taken advantage of. People are accruing a lot of debt for degrees that aren’t going to give them the kind of things they were expecting.”

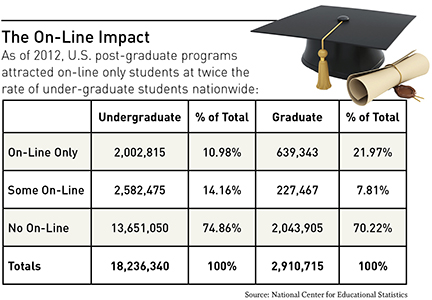

The issue is particularly crucial for the nation’s private, non-profit institutions, which took the lead in promoting on-line education, particularly with graduate programs, and have thrived because of it. While those private, non-profits accounted for only 28 percent of all post-secondary enrollment as recently as 2012, their share of the graduate-school market was a far more impressive 46 percent.

But public universities are continuing to push into that space; U.S. News & World Report’s 2015 list of the Top 25 master’s programs in business, for example, was dominated by 22 public schools, and had just three privates, a somewhat uneven playing field that pits non-profit organizations against programs financed in part with state support.

Beyond marketing trends, other factors such as demographics and technology are putting tens of thousands of degree-seekers—many of them graduate-level students—into play for university recruiters.

Devon Cancilla, vice provost for online education at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, recalls a meeting a couple of years ago, where he spoke with people from the for-profit world. One for-profit CEO, Cancilla recalls, said that “what we had been focusing on was competition between each other; what we want didn’t fully anticipate was the movement of the public institutions into the online space.”

For UMKC, he said, the concern in a hotbed of competition is losing potential students. “But the flip side, a lot of studies show, is that students taking online courses tend to still take them within about 150 miles of the school offering that degree program,” Cancilla said.

Administrators at regional universities, both public and private, say the factors that will ultimately shape a student’s choice are the reputation of the school, the quality of the program offerings and a pricing structure that ensures value.

“There’s no way little Baker University, with our current model—an accelerated evening program for working adults, using part-time scholar/practitioners from the community as faculty—can finance entrepreneurial efforts like the Bloch school at UMKC,” says Dan Falvey, director of Baker’s School of Graduate and Professional Studies. But Baker is able to capitalize on a specific niche of students who want to continue working while getting their degrees, and want to do it locally—a majority of its on-line students live within a 50-mile radius of a Baker campus. “They are seeking convenience,” Falvey said, “as well as the small-school care and attention and proven quality curriculum.”

But a proven curriculum itself is a moving target, one that must change—and quickly—to accommodate changing needs of students. That’s why Baker is preparing to roll out a series of initiatives in 2016 to add bench depth to its lineup of course offerings and concentrations within existing degree programs, Falvey said.

Quality, said Tharp, is going to be a key differentiator for on-line programs. “As the collapse in for-profit continues, there is going to be market share for these folks to claim,” he said. “What we have to do is make sure we apply the same kinds of thinking to on-line that we do on campus, in terms of people’s ability to pay for the degree, the ability to pay back loans they get, the usefulness of that degree.”

At Park University, an early position as a national leader in on-line education for initial degree completion and attainment has translated into success with graduate on-line instruction. Laurie DiPadova-Stocks, dean of the School of Graduate and Professional Studies there, cited a personal experience that reinforced the need for quality programming.

“One of the advantages we have is small class sizes,” she said. When her daughter first entered Arizona State University, she recalls, some freshman-course classrooms held 600 students, or more. “Mom, I can hardly see the professor on the stage, and it’s hard to understand what the teaching assistant is saying. They’re just driving us in like cattle,’ ” her daughter told her.

But at Park, even the on-line classes are capped at 25 students. “You want every student engaged,” DiPadova-Stocks said. If 20 students in a course meet for three hours a week, she said, by default there are limited opportunities for such engagement, and students often prepare with that in mind. But online? “These people have all week, and let me tell you, they are on it all week,” producing in-depth papers and supporting documentation.

Jim Spain, vice provost for eLearning at the University of Missouri, said advances in the technologies for delivery of instruction would continue to break down geographical barriers of the past. Brand presence, strength of reputation for the university, competitive pricing—all will be determinants of an on-line program’s success, he said. “That’s been our focus at Mizzou as we’ve built our online degree programs,” Spain said. “Do they meet the educational needs of learners, are they in programs where we have strengths, and are we at a price that’s affordable and competitive.”

MU’s master’s in public administration and public health and it’s doctoral program in nursing, he said, are three in particular that stand out for students nationwide and internationally. “Last year, we had students from all 50 states and 48 different countries from outside the U.S. in our graduate and undergraduate programs,” he said.

With corporate tuition assistance down, students are carving new pathways

Through the depths of a downturn in 2006, a recession that started in 2007 and the flattest recovery in America’s post-rec-essionary history, administrators of MBA programs designed for working executives have waited for corporate reimbursements levels to bounce back. And waited . . .

It’s likely to be a very long wait.

Despite some reports that companies are resuming their investments in the continuing education of promising young executives, little empirical evidence exists to demonstrate a real bounce-back. But there’s plenty of anecdotal evidence to show that eMBA programs never again will see those levels of company-paid tuition.

That model used to account for two-thirds to three-fourths of students in any given eMBA class offered by Washington University in St. Louis, said Stuart Bunderson, associate dean and director of executive education. “With the economic challenges, companies scaled back from those expenses and they never really scaled back up.”

That trend has profound implications for what’s happening in executive education, administrators say. For one, the expectations of students footing their own bill means that they’re looking for something that differs substantially from what a company may have wanted in a graduate. “If a company is paying, it knows exactly what that employee will be doing when he or she is finished,” Bunderson said. “And that’s not to change careers, or move. With the increased percentage of self-funded students, they may be more interested in career transitions, or even thinking a bit differently about crafting their careers.”

Smart companies, say program administrators, know that the costs of an eMBA—which in this region can run from $36,000 at Park University up to nearly $120,000 at Washington University’s Olin school—can pale in comparison with the high costs of turnover from the loss of a key employee or two, especially if those young executives move to a competitor. For them, Bunderson said, the eMBA is an opportunity to develop people, keep them engaged, and create loyalty. “That’s worth it,” he said. “If you have five people moving up the ranks and this makes it more likely to keep one or two at a higher level of performance, investing in an eMBA is a no-brainer.”

Another fundamental change is that more self-funding students are looking for the return on their own investments through entrepreneurship. “Now, we get a lot of people who want that,” Bunderson said. In surveys of what students are looking for, the consistent No. 1 answer, he said, was a better understanding of what entrepreneurship entails. “People want to know how to start a business, develop a business, and identify new, profitable business ideas,” he said. “Once they have that new idea, they want to know how to fund it and how to build a team around it. And that’s not just us: A lot of eMBAs are offering electives with a focus on entrepreneurship.”

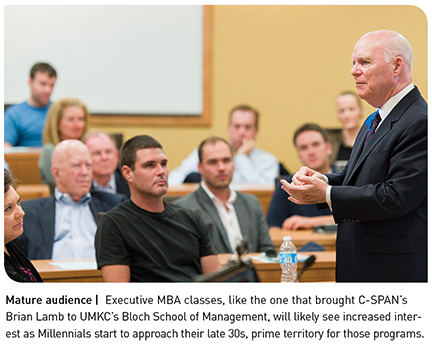

The most positive trend that administrators can point to is that the upper end of the Millennial generation is approaching its mid-30s, on the cusp of where most eMBA programs find their best prospects. And considering that this generation is now the largest in U.S. history, larger even than the Baby Boom, the prospect pool is about to deepen significantly.

That will pose questions that program administrators haven’t yet been able to fully anticipate. Take on-line vs. classroom instruction. “As the younger people move into eMBA education, one question is, will they want to change that mix?” Bunderson said. “On line vs. on-ground is already a mix, but will it be the optimal mix? We anticipate that the optimum balance a student is seeking for mode of instruction will shift.”