HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

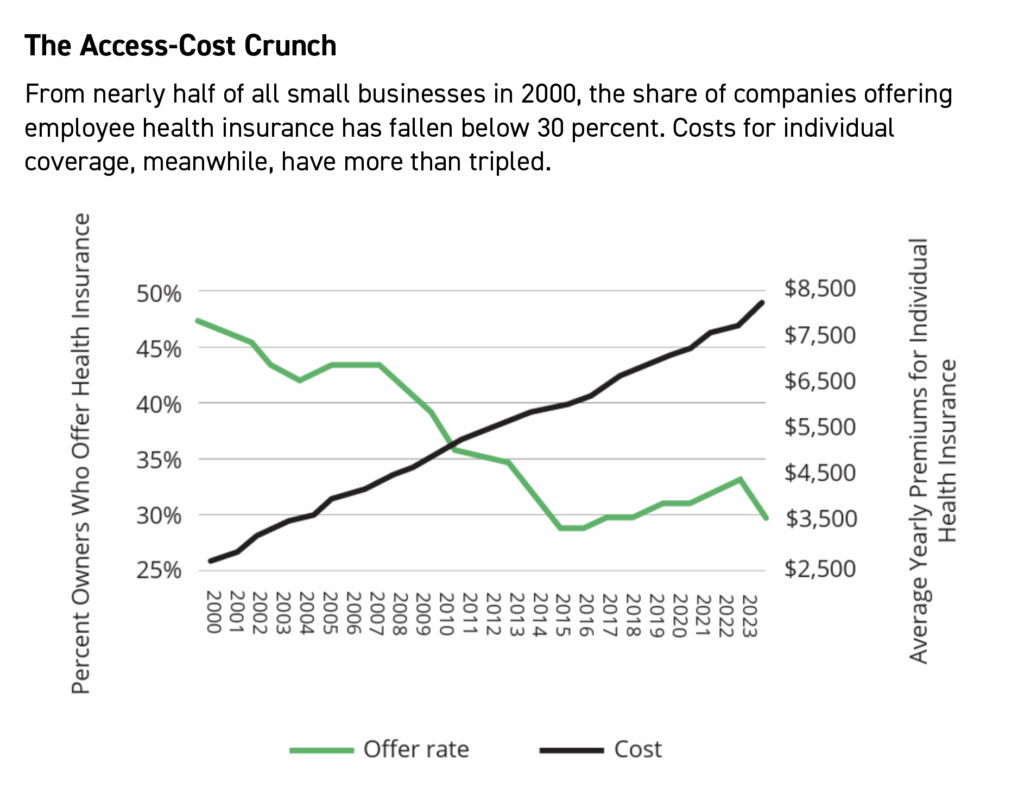

As employer-provided health-insurance numbers continue to crater nationwide, small businesses struggle for solutions. Answers, however, are proving elusive.

The average age in America is 38.7 years as of 2024. Over that span, small businesses have been fighting to corral the rising costs of providing health insurance for their employees.

“A ton of small employers really would like to put a plan in place to attract new employees, but they are very apprehensive to roll the plan out because of the cost of coverage.” — Andrew Martin, Holmes Murphy & Associates

Spoiler alert: They’re losing.

“The small-group market is collapsing, premiums are unsustainable, and small businesses are being forced to make difficult choices,” says Josselin Castillo of the National Federation of Independent Businesses.

“For nearly four decades, health insurance costs have been the No. 1 concern for small business owners, and we are now at a breaking point,” said Castillo, principal of federal government relations for the NFIB. “Without immediate and targeted policy reforms, millions of Americans may lose access to employer-sponsored health coverage.”

Millions already have. Since the 21st century arrived, the share of companies that offer employer-paid health plans has fallen, and over the past decade alone, the decline accelerated by 44 percent—from 15 million covered individuals in 2014 to just 8 and a half in 2023, the advocacy group said in its annual update earlier this year.

Worse, average premiums for individual plans are up 120 percent in the past 20 years; premiums for family plan premiums were even harder hit, up 129 percent for firms with 50 or fewer employees.

For some perspective, the average earnings of an American worker in 1994 were $34,197.63. Last year that stood at $61,984. But even with inflation-adjusted earnings up 81.2 percent, premiums were rising 50 percent faster than compensation.

“It is very apparent there is sticker shock when employers first try to roll out a medical plan to their employees,” said Andrew Martin, client executive for the brokerage specialist Holmes Murphy & Associates in Kansas City. “A ton of small employers really would like to put a plan in place to attract new employees, but they are very apprehensive to roll the plan out because of the cost of coverage.”

Still, he notes, things in this market appear to be rosier than the national picture. “For the most part,” Martin said, “employers in our region seem to be bearing more of the responsibility of premium increases, trying to keep the employees as whole as possible when taking large insurance increases.”

From the provider side, Jenny Housley said Blue KC saw plan retention in the small-group market beat 2024 estimates, with slightly lower numbers so far this year. A number of factors unique to each employer group could be driving that said Housley, senior vice president and chief revenue officer for Blue KC.

“We continue to see pressures in rising costs of health care across all segments,” she said. “To address rising costs, we continue to develop new plans to offset the costs of care for our members and employer group customers in our community.”

As an example, she cited Blue KC’s Spira Care, which has delivered care savings of 8.8 percent compared to similar products. “This saves our employer group partners and members money both in premium and out-of-pocket expenses,” she said.

The need, says NFIB, is urgent: Ninety-eight percent of small businesses say they are concerned about whether they will be able to afford to continue offering health insurance in the next five years, according to its annual report. The reason: They’re bearing nearly twice the burden for health insurance as large businesses carry. Those with less than $600,000 in revenue spend nearly 12 percent of payroll on health benefits, NFIB says, compared to 7 percent for firms with over $2.4 million in revenue.

Solutions, Anyone?

At the federal level, NFIB is calling for stronger protections with employer-sponsored plans, including targeted tax credits for small-business health plans, expansion of the ICHRA program (Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangements), more flexibility for small employers to form pooling arrangements, access to stop-loss insurance, greater access to Health Savings Accounts and elimination of one-size-fits-all mandates, which it says only limit competition and further drive premium cost increases. It also wants Washington to discourage hospital consolidation and promote innovation that will lower the costs of prescription drugs.

Group size, brokers say, can affect the number of plan designs—more employees generally means more options. In general, companies start with a “base” medical plan, offering lower-cost coverage (with lower levels of benefits) and a more attractive employer share of the coverage cost. That’s generally attractive for younger employees and those with fewer health issues.

For others, companies offer plans with greater benefits but pay a lower share of that cost. “Employees who need richer benefits can still reap the rewards of that plan, but they will know they have to pay more to be enrolled in it,” Martin said. “This gives the employer flexibility in meeting the needs of their employees but also offering incentives to enroll in a less costly medical plan.”

He said the ICHRA piece may be among the best strategies.

“By using the ICHRA model, employers are able to set a budget for each employee where they decide how much money they would like to offer them,” he said. “Then, the employee is able to use those funds to purchase their own insurance from the individual market. This not only offers the company cost control, but it also gives the employees flexibility in being able to choose the plans that fit their needs.”

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

On top of that, he said, there are no minimum participation requirements for companies that offer an ICHRA. But there are drawbacks.

“While this can be a great solution for some, it also can create complexity in the way it is administered,” Martin said. “There are certainly downsides to this, in the fact that it creates more of an administrative burden for the employer and can sometimes be confusing for employees to be sent out on their own to shop and enroll in insurance.”

Business sector diversity, company workforce sizes and other factors complicate broad solutions, and innovation remains paramount.

“There’s not a one-size-fits-all response,” Housley said, “but in general we see our small-group employers adjusting plan offerings and employer contributions in order to continue to provide high-quality access to care for their employees. In some cases, this means offering a new plan on another network.”