HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

The term is often overused, but with half the nation’s small businesses expected to change ownership over the next five years, we truly are at an inflection point.

Whether it involves preparing to capture the value of a lifetime’s worth of work, handing it off to another generation, or creating a lasting philanthropic legacy, more business owners need expert guidance today than ever before. That imperative brought two dozen business-valuation experts, lawyers, wealth managers and other relevant players to the offices of UBS Financial Services on Aug. 13 for the 2019 Wealth Management Industry Outlook assembly. Deftly co-chaired by James Lipari of UBS and Nikki Newton of UMB, the panel explored a range of issues that confront potential sellers and buyers in a highly active market. More than just the business fundamentals, though, the assembly explored the psychology behind a business sale, the possible pathways that give meaning and purpose to an owner’s life after the sale, and the relationships that are keys to maintaining a successful enterprise for buyers.

A Fundamental Challenge

The issue of business succession is fraught with enormous consequences for the American economy. Estimates vary, but suggest that roughly 300,000 businesses in the U.S. have revenues between $5 million and $500 million. Those companies employ a third of the U.S. work force and crank out 40 percent of the nation’s $19 trillion GDP.

Jim Lipari

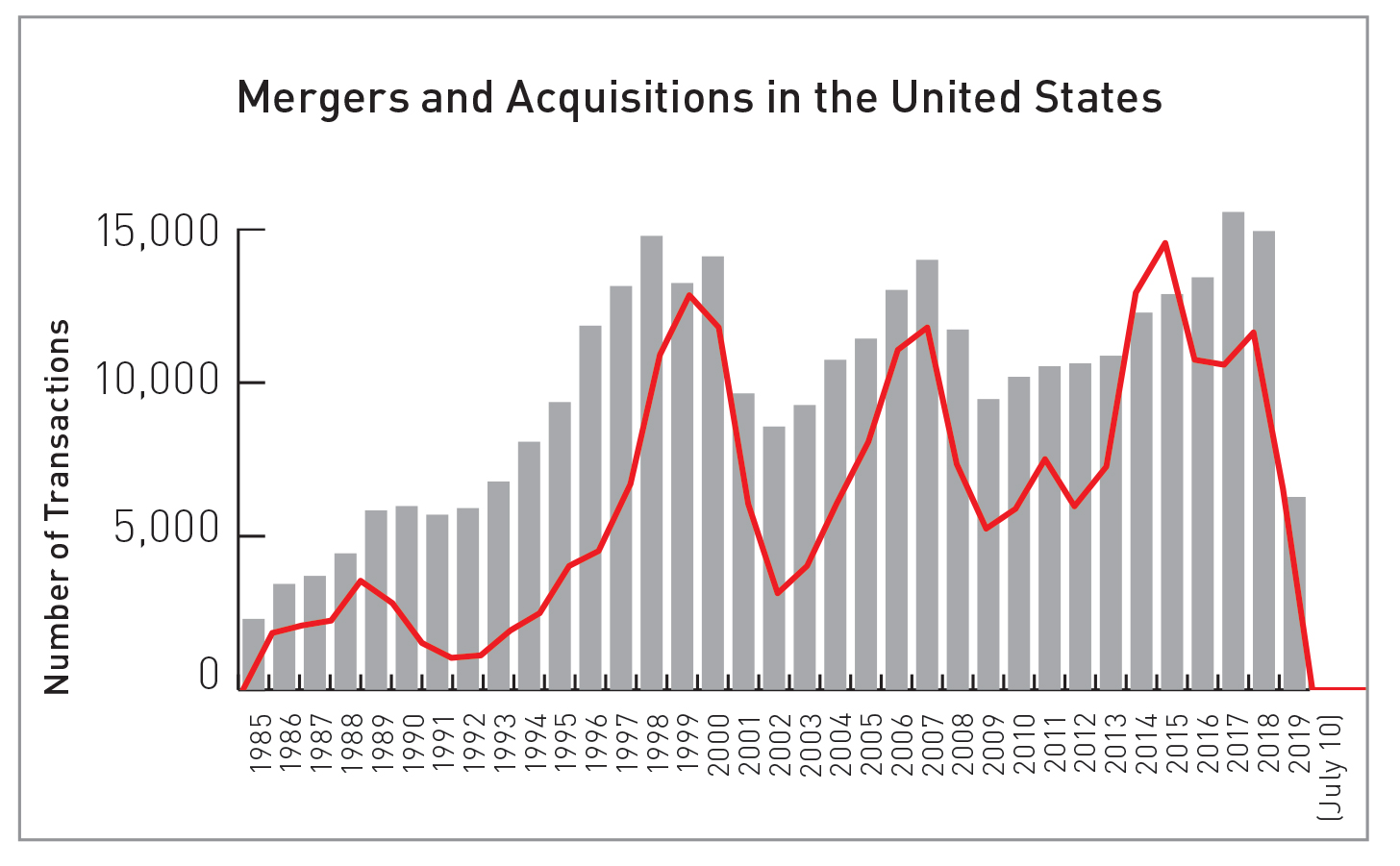

According to BizBuySell.com, in just five years, from 2013 to 2018, the number of U.S. companies sold surged by 46.14 percent, hitting a record 10,312 in 2018—a number that many expect to see go much higher in the coming years. Jim Lipari of UBS cited projections that half of small businesses in America could sell within the next five years, and 60 percent within a decade.

The matter takes on proportions of crisis because the average age of business owners already surpasses 60, and the majority still don’t have succession plans. Lipari outlined a discussion focusing on how owners maximize the value of a business, what they need to do to plan for their wealth beyond the business, and what life should look like after a sale. The latter, wealth managers say, is all too often overlooked in an owner’s efforts to maximize the value of a company before a sale.

The implications for the nation and its work force are huge: Small business accounted for 58 million jobs in 2015, nearly half of the 124 million total (a figure that has since ballooned to 157 million). Four out of five companies in the U.S. have fewer than 500 employees.

A considerable majority—three in five, overall—have no employees, but for those who do, there is a unifying concern, assembly participants said.

Stephanie Klingzell Carlin said a current disruptor she hears from clients across sectors involves “the war for labor—the shortage of qualified and skilled labor, in almost any industry. It doesn’t matter who I’m talking to, it’s the difficulty in finding good people to come to work for them.”

But owners are taking action to address that, especially in the manufacturing sector. Tom Smith, of the Business Owners Advisory Services unit at U.S. Bank, said that “the  amount of automation they’ve implemented has been remarkable throughout the region to solve that labor issue.”

amount of automation they’ve implemented has been remarkable throughout the region to solve that labor issue.”

Just a day before the assembly, co-chair Nikki Newton of UMB Bank had lunch with a score of business owners. “Prior to that, I would have said valuation” was their biggest concern, he said. “But after that, everyone said they had labor and hiring constraints. That’s a big concern.”

Neither is the labor issue limited to clients. Mary Lucas, director of financial planning at UMB Bank, noted that “clients and business owners are becoming more sophisticated, so we need to be able to have support for that with labor or talent behind the scenes to meet them one on one.”

Tim Helfer of Sagemark Consulting, part of the Lincoln Financial Group, said the labor challenge comes at a particularly bad time for some. “I’ve found a struggle with the business owner who is in the stay-and-grow mode,” he said, “helping them gain and garner the efficiencies they need to have to grow to get to the next level. It goes to the talent pool of finding someone. They’re not ready to exit or the timing is not right, so how do you get them to that position and nurture them along?”

Despite the current favorable climate for selling, timing can be a huge consideration, especially if there’s a downturn. “I tell some people to think about getting out sooner, before their earnings and EBITDA contract,” said Tom Smith. An owner looking to sell within two years may need five or more years to reposition his company if an unexpected downturn occurs; are they willing to risk the need for that kind of commitment by not selling now?

Another complication for owners, said Seigfreid Bingham partner Cindy McClannahan, is “constant change in the tax law, the fact that they don’t feel they can plan either for business operations or personal estate planning as to what the law’s going to be over the next five years. That really affects their

planning, which means they are constantly reinventing their plan.”

Ed Kerley

Owners are also caught up in global-economy shock waves, in ways they haven’t been previously. Ed Kerley, of Country Club Bank’s wealth solutions unit, said that “gone are the days of ‘My kids don’t want anything to do to with it, and competitors don’t have the money to buy me out’. Now we have the global dynamics and our clients don’t understand the mechanisms of that.” That, he said, leads to uncertainty, and many owners in the face of that will fail to take action to position for a sale.

Jené Hong, partner with O’Keeffe and O’Malley, said it’s important for owners to understand the difference between succession planning and exit planning. “That includes discussions with the children, because in most cases, we’re finding out that the kids want nothing to do with it.”

An added concern, she said, can be the nature of the business. “With a lot of these companies, people don’t find them sexy, so they’re not interested in buying it if they’re not the traditional buyers—competitor or somebody who wants to get into” that line. As a result, she said, “I’m concerned about who is going to build our roads, who will roof our houses, who will remodel our bathrooms, because people aren’t wanting to do it.”

Often, said Spencer Fane partner Scott Blakesley, “even companies that don’t appear to be family related, are family related.” And within that cate-gory, many families “can’t keep the family stuff either separated or properly coordinated. The issues they are fighting over on a family transition or business buyout have nothing to do with this transaction, but something Mom did to you 50 years ago and you haven’t forgotten it.”

That, said Julius Madas, market president for INTRUST Bank, is where better communication can help. For owners being held back, he said, it often “comes back to a lack of planning.” Even at a large, fourth-generation family bank, he said, there are benefits to continually challenging processes, examining goals and communicating plans broadly—traits that can benefit small companies as well as large.

Despite challenges for owners, both external and internal, this is perhaps the best time in history to be selling a company with solid earnings and growth potential, several participants said. UMB’s Dan Weeks, based in Denver, said a huge amount of private-equity money is “chasing very few deals. Valuations seem to be stretched, and it’s a good time for business owners looking to get out.”

Agreed, said Terry Staley, a tax partner with MarksNelson. “Valuations are at an all-time high right now,” he said. “Buyers taking over are wondering how do we use the cash flow then? If we have a dip in the economy, what happens? How do we pay for it?”

Terry Staley

One factor holding back some owners, said Staley’s MarksNelson colleague, Rob Metcalf, is a misguided cost-benefit analysis regarding the work needed to prepare a company for sale. “Business owners have a hard time doing that transition, and many are not willing to necessarily pay the price to prepare their business for sale and clean up the things they need to clean up, because it’s going to cost them. Yet, you’re trying to convince them that the monetary payback is worthwhile. Sometimes they are hard to convince.”

Owners looking to position for a sale would be well-advised to demonstrate how tangible property is being put to its best use. Steve York, of Stern Brothers Valuation Advisors, said that aspect was “kind of exciting and frustrating at the same time. There are quite a number of unicorn businesses in that area where tangible property has not been commercialized, is not cash-flowing. Trying to develop a value on that is interesting.”

Creating/Enhancing Value

Steve York also succinctly summar-ized what buyers are looking for in an acquisition: “It’s a history of proven cash flow or the expectation of future cash flow,” he said. That said, things going on in the tech sector, in particular, are changing that dynamic—some high profile companies have gone public with-out ever having made a profit.

Simple actions go a long way to enhancing value. Jené Hong said that if a buyer is asking for financials in July or August and an owner still has no tax returns for the previous year, that’s a red flag on a sale. “When you have control over that,” she says, “buyers see that as having your house in order.”

“It is like selling your house,” said Step & Rothwell managing partner Ken Eaton. You can try to entice a buyer when

the closets are a mess and the home is cluttered, but “you get the best value when it’s clean.”

A key part of the valuation process that often applies to family-held businesses, said Rob Metcalf, is implied rent. Often, a family-owned company also has real-estate investments that include less-than-market rents for the enterprise. That has to be factored into the equation when assessing real-world profitability and cash flow.

Knowing where your company stands relative to competitors in this market, and within your sector as a whole, is also a key. “Buyers want higher-than-average revenues and profitability,” said Dan Weeks.

Taking Control

Successfully positioning a company for sale, participants said, is a long-term process, not a singular event. In that way, it’s not unlike long-term wealth management.

Ken Eaton said that amid market uncertainty, sharp reversals in interest rates and Chinese tariffs, “business owners can change their minds on a daily basis about whether they think it’s time to exit or not. We have to calm those waters down.”

Jim Lipari cited research from the Exit Planning Institute that said owners who had exited their firms, by wide margin, weren’t happy with the way the process played out. “Three in four are dissatisfied with the way they did exit,” he said.

Dan McBroom

A Need to Act

Fixing that, said Dan McBroom of Capstone Headwaters in Denver, is an imperative. Too often, he said, owners on their own go into negotiations with far larger buyers who are armed with legal and financial teams. “It’s really unfair,” McBroom said. The tragic part, he said, is that in the current climate, “I can’t find a single thing to complain about if you’re a business owner.” There has never been, he said, “a bigger bid/ask in the sub-$250 million enterprise value space.”

His firm works to bring competing buyers to the table, because a single prospective buyer does not constitute a market, but he’d like the advisory sector to do more for owners. Too often, “great business owners are out there, walking into a fight with nothing at their side,” McBroom said. “It’s sad. “

Rob Metcalf said proper preparation entails a number of tactics that go beyond searching for the right buyer. Owners also need to ensure that the management team will remain in place, and must understand that events may change the sale-date calculus.

“You can think ahead five years prior to the sale,” he said, “but other times, buyers come out of the blue, and some owners didn’t even know they were looking at a liquidity event.” At times, he said, owners will “pull the trigger who are not at all prepared for that.”

Another potential complication, said Jené Hong, is death or illness of the lead person in a family business, often without a plan in place. Some owners, she said, say they have no plans to ever leave. “Really? Tell me more about that,” Hong says, “’I assure you, you’re leaving. Do you want to leave planned or unplanned?’”

Thus, several at the table said, it’s important for owners to have realistic expectations of what their company is worth, rather than unsubstantiated gut-level guesstimates.

As Jené Hong said, someone whose wants a $3 million payday for a company losing $500,000 a year will be sorely disappointed. With a realistic valuation in place, and a vision for what life after a sale will look like, the process can focus on how a company gets from the former to the latter.

Cindy McClannahan

One key piece of that path, said Cindy McClannahan, is ensuring that key employees are locked in, not poached by others firm that will offer them more money. “And it’s important for every business owner to have a list of the top five things somebody needs to know if all the sudden they are in a car accident on the way home. Make sure they have that in the drawer of their desk so somebody can step in and try to start running the business.”

Tom Smith said his bank’s guidance for owners is “manage the business as if you were going to sell, whether you’re planning to or not. How would a buyer look at that business today?”

That, said several at the table, is a defining difference between long-term owners and serial entrepreneurs, who are always looking to capitalize with a sale.

It’s important for owners to under-stand, several said, that they’re not likely to ever get 100 percent cash on a sale, and that the terms of their exit trans-action can vary widely. In some cases, they will involve equity stakes under the new ownership, in exchange for staying on in a transitional role (which introduces issues of another sort with relinquishing control).

Life After the Sale

Jim Lipari asked how advisors can help owners with the sensitive issue of helping owners with their evolving sense of identity, both with letting go psychologically, and with the way their newfound wealth changes their sense of purpose in life.

“A lot of times, selling is about letting go,” said his UBS colleague, Zach Zarda. After a sale, “some owners are elated, but others are depressed and seem to lack purpose.”

Katie Gray, of the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation, spoke to the challenges—yes, there are some—that come with a sale and the instant wealth it can generate.

Katie Gray

“This may be all the charitable money that’s ever going to be there in their life, all coming in this one transaction,” she said. “So it’s difficult for the seller to think about, there’s just a lot to do, and the charitable piece is often kind of an afterthought, understandably. But it’s so beneficial to get it done” before the contract is signed.

Evan Lange, of the global Christian foundation The Signatry, also deals with sponsorship of donor-advised funds. He encouraged those in transactional roles to make the charitable discussion part of the initial assessments that take place with valuation, tax planning and wealth-management strategies.

“Gifting a part of that interest before a sale, there are specific regulations in the code that require that gift to be made before there is a binding obligation to sell the company,” he said. “Sometimes we get the call, ‘Hey, I’m selling on Wednesday, can I do a gift?’ It might be too late at that point. There can be tremendous tax benefits before a sale, but you have to have a plan in place.”

Even when a sale goes as planned, when retirement or second acts in business might beckon and when a philanthropic legacy has been established, considerations must be addressed about how life will look like after the deal is done.

Part of that is the mark they want to leave on their communities, Katie Gray said. “Donors never talk about tax deductions driving their gifts—that’s never the point. It’s leaving a legacy.”

Ed Kerley pointed out that some owners will find themselves back at the company within a year or two, occasionally even buying it back—often at a steep discount—after selling to someone who wasn’t capable of managing it. “It’s not all about how we get the multiples and get the biggest bang for the buck and go to Naples for the winter,” he said. “We have to look at what happens if it doesn’t work out. That’s planning. That’s really getting into the weeds.”

As Jim Lipari observed, one of his goals as assembly co-chair was to help assemble a group and orchestrate a discussion that would be of benefit to owners and advisers alike. “One of the things important to me was to bring a collaborative group to table with different perspectives,” he told participants. Through such conversations, he hopes, professional advisers can better help owners deal with this wide range of seemingly intractable issues.