HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Demographic trends do not augur well for business hiring. But that doesn’t mean employers are left without options to secure talent.

PUBLISHED FEBRUARY 2024

The January jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics caught economists nationwide off-guard: Nonfarm payrolls soared 353,000 for the month, nearly double the Dow Jones estimate of 185,000. The unemployment rate, projected to tick up a notch to 3.8 percent, held serve at 3.7. Average hourly earnings, meanwhile, doubled projections by a popping 0.6 percent for the month and 4.5 percent year over year—again, beating expectations of 4.1 percent.

Does any of this sound like a recession is in the offing, as predicted at the start of the year by a host of economists?

Hidden in that rash of positive metrics, though, is a concern that some executives say should be top of mind for companies seeking to hire in this climate: The long-running battle for talent is about to become an even greater challenge.

Two factors are driving that: By now, retirement age has come calling for well more than half of the Baby Boom generation, which at its peak was the largest in the nation’s history. Over the next eight years, the remnants of that cohort will hit full retirement age of 67. That represents a huge loss of institutional memory for American business.

The other end of the pipeline, though, may present even bigger challenges for businesses and the economy. And the reason is simple: Considerably fewer Americans are finishing college now than was the case when enrollments peaked in 2010. Nationwide, the number of students in college has fallen from 21 million to 19 million, a decline of nearly 10 percent.

“The decline in college enrollments warrants careful consideration at a regional level, especially given the established correlation between higher education and higher wages,” says Lia McIntosh, director of the Civic Council’s KC Rising job-growth initiative. “The evident impact of COVID on student enrollment and completion raises questions about the potential implications for the availability of skilled talent in the future.”

Buried in the numbers, though, are some bits of sunshine, especially within specialized programs at community colleges, such as advanced manufacturing. “This positive development highlights a growing demand for immediate job opportunities that do not necessarily require a degree,” McIntosh says. “It emphasizes the importance of fostering growth in specialized, skill-oriented programs to address the specific workforce needs of our region.”

Amid those trendlines, employers must change the way they do business if they’re going to acquire critical talent.

“The days of showing up at a career fair and hiring students are long gone,” says Shawn Strong, president of State Technical College of Missouri, a two-year institution. “If you haven’t been building a partnership along the way, the odds of hiring students are greatly diminished. Businesses know the value of relationships in business dealings. Hiring graduates is no different. Employers need to get to know the faculty, get in front of students, and consider formal partnerships.”

Successful hiring programs today involve such strategies, as well as effective use of tools like social media platforms, human-capital management programs to evaluate and correctly place candidates in the right job silos, candidate lead-generation programs and, of course, tried and true approaches that are as simple as picking up the phone, an effective strategy when attempting to connect with job-seekers inundated by email solicitations thrown off by job search engines.

Hiring managers can also do their organizations a favor by keeping current on what area colleges and universities are doing to adjust academic programming to fit emerging business needs. KU’s Edwards Campus in Overland Park, for example, launched new bachelor’s degree programs last year in its professional studies program, with a concentration in applied data analytics and in the applied science track in cybersecurity.

“The data-analytics concentration gives students a strong foundation in professional management as well the opportunity to develop their data-science skills while solving real-world problems,” said Stuart Day, the Edwards Campus dean. “This is the type of knowledge industries want from their employees to make better business decisions.”

The cybersecurity track aims to fill an especially high demand nationwide. The BLS projects jobs in that realm, by 2031, will have exploded by 35 percent over the previous decade. And they’re good ones: Roughly 19,500 openings for information security analysts come open each year with a median annual salary of $102,600.

Not far away, at Kansas State’s Olathe campus, plans are in motion for a physical expansion to accommodate more bioanalytical testing, advanced manufacturing, and lab work. Last fall, it announced new programming in advanced manufacturing and supply chain, as well as efforts to elevate existing research activities, partnering with university and regional researchers to become a leader in community health and uses of food as medicine. By Spring 2025, it will offer bachelor’s degree completion programs in engineering technology with an emphasis on robotics and automation, electrical and computer, and mechanical applications.

Adding new programs at the post-secondary level requires a strategic approach, said Strong.

“It is probably a lot less intentional and more organic than most would think,” he said. “You need three main components for State Tech to consider a new program: demand, funding, and student interest. Right now, there is demand for about every job out there. The biggest hurdle is student interest. We have to be able to fill the program. That typically means we need 50 new students entering the program every year. That’s a lot harder than it sounds with our current low unemployment rates.”

That’s a challenge he and his peer in two-year instruction are likely to confront for some time.

“Traditionally, when the economy corrects itself, you see an increase in enrollment in community colleges,” he said. “While the data may not support it, the historic economic cycle says we are way past due for a correction. When that happens, I don’t think we are going to see a traditional uptick in enrollment because there is such a shortage in the labor market. In two years, we will start to see a long-term trend with smaller high-school graduating classes. I am a little more bearish on enrollment; I think this is the long-term norm.”

Still, State Tech has definitely bucked the trend. The Linn-based two-year skills training specialist saw enrollment soar from 1,471 in 2018 to 2,279 last fall—an increase of 53.9 percent. With the exception of a 0.3 percent uptick at East Central College, State Tech was the only two-year program to see enrollment growth over those five years.

Call for Collaboration

On a broader level, said McIntosh, collaborative efforts between educational institutions, businesses, and workforce training programs continue to be vital to align education with industry needs.

“KC Rising is actively exploring strategies to enhance coordination and connect talent with job opportunities across the two-state region,” she said. “Organizations like the Full Employment Council in Missouri, Workforce Partnership in Kansas, Great Jobs KC, and community colleges on both sides of the state line are evolving to meet immediate employer needs. Specialized programs and apprenticeships, supported by employers, represent a growing trend to address the pressing demands of the job market.”

The battle to fill those demands is most assuredly being fought at the community college level. Greg Mosier, president of Kansas City Kansas Community College, can recite a litany of collaborations with business to produce workers, especially in the advanced-manufacturing sector: The Panasonic Energy battery plant under construction in DeSoto (projected employment: 4,000), Orange EV’s new production facility in Wyandotte County (185 new jobs) and a new plant for a subsidiary of Minnesota-based Marvin Windows (600 jobs).

All, he said, will require higher-level instruction, and generate higher-paying jobs. America, Mosier says, has a skills gap, one his team is working to close locally.

“Am I optimistic? Absolutely,” Mosier says. “Every day in Wyandotte County, when we have close to 7,000 unfilled positions, we need people with the right skill sets. That’s where community colleges come in.” They are certification for workers who can immediately step into jobs at $50,000 a year, follow up with an additional level of instruction and qualify for the $60,000-$65,000 range, and continue working to move up their organizational ladders.

“It’s a change from what colleges have been used to doing in the last 30 years or so,” Mosier says. “But as someone coming here from the business/industry side, I can tell you that we are well ahead of the curve on that one.”

The Campus Conundrum

Higher education has long been a standard by which metropolitan areas measure the quality and competency of their work forces, the backbone of economic-development potential.

But if regional and national enrollment figures are an indication, that spine is fractured.

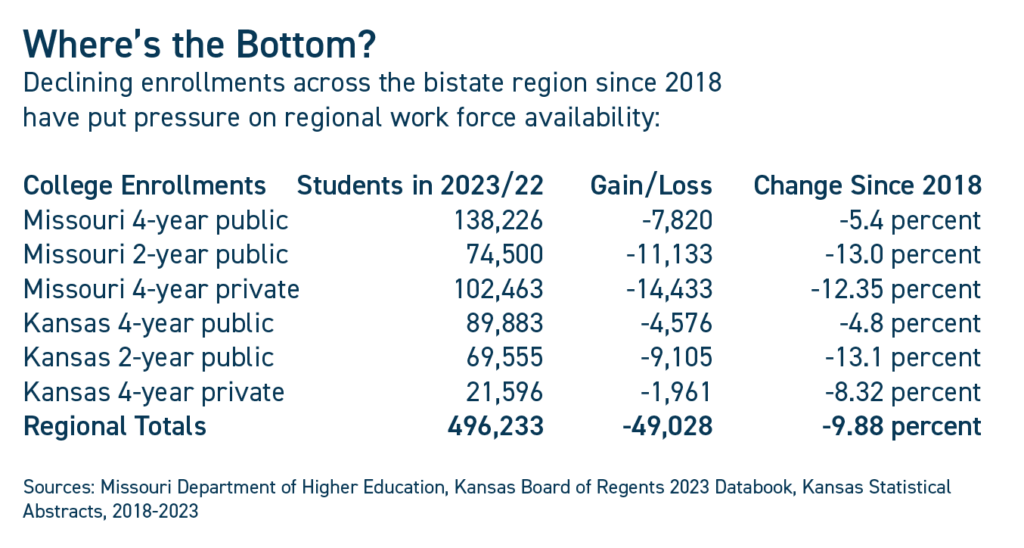

As the nation has witnessed overall college enrollment plummet by 10 percent since peaking at 21 million in 2010, Missouri and Kansas have witnessed potentially more concerning rate of decline—9.88 percent in just the past five years.

That retrenchment occurring should come as no surprise to anyone in higher-education administration: Benedictine College president Steve Minnis, in 2009, cautioned that demographic trends would throttle enrollments over the coming decade. He may have been even more correct in his assessment than he thought at the time.

The chart below reflects not just the depth, but the breadth of a decline that should terrorize any corporate HR officer or recruiter. The competition for qualified college graduates, especially in the STEM disciplines, is getting more intense by the year.

Colleges across the board are living it out—four-year public universities and private colleges as well as the two-year community-college systems in each state. The decline is not rooted solely in consumers’ reassessment of the value proposition behind a four-year degree; these are not 16th-century French poetry programs being hammered. Even Missouri University of Science & Technology, a point of pride in state’s STEM ecosystem, has struggled, shedding 16.8 percent of its overall enrollment over the past five years.

Colleges across the board are living it out—four-year public universities and private colleges as well as the two-year community-college systems in each state. The decline is not rooted solely in consumers’ reassessment of the value proposition behind a four-year degree; these are not 16th-century French poetry programs being hammered. Even Missouri University of Science & Technology, a point of pride in state’s STEM ecosystem, has struggled, shedding 16.8 percent of its overall enrollment over the past five years.

The biggest declines, in percentage terms, have fallen on the community colleges in each state, and by nearly identical margins: Down 13 percent in Missouri and 13.1 percent in Kansas. But observers believe that may be more of a cyclical phenomenon than a structural one. Those enrollments tend to rise in difficult economic times, as people look to enhance their skill sets before an anticipated recovery.

The Benefits of Scale

The biggest institutions, meanwhile, are holding up comparatively well. The main Columbia campus of the University of Missouri system actually recorded an increase of 3.9 percent over that period, while state-funded schools outside the MU system produced a couple of eye-popping returns: Northwest Missouri State soared by 40.9 percent, and the University of Central Missouri had a solid 11.3 percent surge.

The bigger concerns were at some of what might be called directional schools: Missouri Western dropped 32.9 percent and Missouri Southern fell 31.8 percent, while Truman State grappled with a 37.8 percent plunge.

On the private-college side, Saint Louis University welcomed a 19.1 percent increase, edging out Evangel College’s 18.2 percent for the biggest increase. But six other Missouri private colleges saw their numbers fall by more than 30 percent, topped by Columbia College’s 49.9 percent drop and Park University’s decline of 43.2 percent.

On the Kansas side, KU and Wichita State were alone among Regents schools to see higher five-year headcounts, tho-ugh K-State officials were pleased to see several years of declines broken with a slight increase last fall. Still, it left the state’s second-largest university down 11.4 percent since 2018. Emporia State was hammered with a 19.3 percent drop, and Fort Hays State was down 17.3 percent, while Pittsburg State’s numbers fell 13.5 percent.

Private schools in Kansas, like those in Missouri, saw boom or bust, but an overall decline. Four institutions, led by Manhattan Christian’s 33.3 percent loss, were down over 20 percent since 2018, four more saw double-digit gains, led by Kansas Wesleyan’s 16.8 percent pop in Salina. Ottawa University, Bethel College and Benedictine enjoyed healthy increases.

As in Missouri, community colleges were hit hard. Of the 19 institutions under the Regents aegis, only Dodge City posted a five-year increase, a respectable rise of 12.6 percent. Johnson County Community College, the state’s biggest, saw its headcount dip 6.7 percent; Kansas City Kansas was off 18.6 percent. Worse, the aggregate 13 percent decline across the system since 2018 hit 21.9 percent over a 10-year period.