HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Throughout its days of youth and into what’s now popularly referred to as the Silver Tsunami, the Baby Boom generation established itself overall as the healthiest, longest-living cohort in American history. Generation X picked up on that and raised the bar for life expectancy at birth in both men and women.

But the activities that came in cultural waves—from Hula Hooping to jogging, aerobics to jazzercise, P90X to plyometrics—often came with a price. “Our bodies weren’t designed to be pushed the way we’re pushing them,” says Burrel Gaddy, an orthopedic surgeon with Midwest Orthopaedics. “This generation wants to be active: They’ve exercised, and we’ve promoted the idea of exercise, but we need to be careful about impact activities. They’re not the best things for us, and unfortunately, what we’re seeing now are the ill effects of a very active lifestyle.”

To which the Baby Boomer awaiting knee replacement might think: “Now they tell us.”

It’s true, though: Years of pounding while running, or playing tennis, racquetball or basketball, have produced a cumulative effect that is showing up today in the offices of orthopedic surgeons, ergonomic specialists, and physical and occupational therapists. While that’s happening, innovations in surgical techniques and materials have spawned increasing numbers of procedures once thought of as something from the Six Million-Dollar Man.

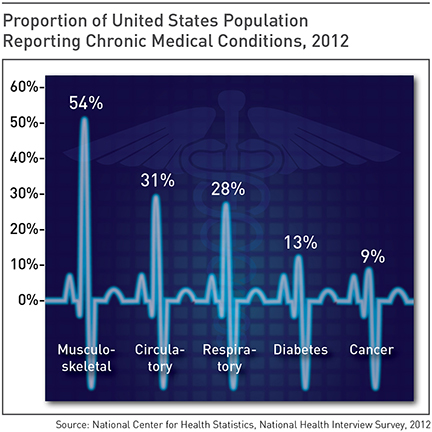

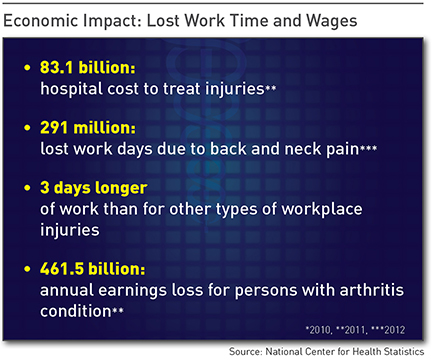

Those trends form a twofold concern for today’s business executives. On a personal level, it’s an issue for both Boomers and the leading half of Gen-X: They’re largely mid-40s or older, deeply entrenched in an executive lifestyle that entails too much sitting, too many long days, too little exercise and too many bad dietary choices. On a professional level, it’s a concern because their employees are part of a work force whose average age continues to rise, with the attendant issues of age-related bone and joint conditions.

Among the many factors that produce today’s orthopedic patients, says surgeon Kim Templeton of the University of Kansas Hospital, two stand out: A history of past injury, and more recently, a lack of regular exercise. For the former, sports-related injuries like torn ACLs are precursors to arthritis later in life. “That articular cartilage doesn’t really heal the way bone and other tissues do,” she says—despite reconstructive surgery, that stays damaged. And for reasons still being studied, she says, the risk is higher in women, who see the ill effects years earlier than men.

James Reardon, an orthopedic surgeon at Northland Bone and Joint, points to the fitness factor—or lack of one—as a current culprit. “You can directly correlate the number of replacement surgeries we do to the weight of the population in the U.S.,” he says. “We’re now seeing people with BMI measurements of 45 and 55,” when obesity is generally defined as 30 and above. “We have to buy bigger MRI scanners and bigger operating tables because patients are too heavy to be evaluated with the equipment we have.” Replacements for hips and knees, he said, are directly related to the weight of a patient above those bearing joints.

Because everything in the body is connected to something else, Templeton said, it can impact something else. “If you do have joint pain and are not able to exercise, that dramatically impacts your ability to take care of other health issues—weight, cardiac, diabetes. If you’re hurt, it’s harder to control those other conditions.”

Those co-morbidities, says Dan Weed, an orthopedic surgeon for Saint Luke’s Health System, “are one of my biggest problems. They make surgery harder, they make disease worse, they make the patient less active before surgery and they make it difficult to get back to activity afterward.” Take diabetes, for example. “It makes incisions heal slower,” Weed said. “It’s a horrible problem: Almost every person I see is overweight.”

Michael Bledsoe of Mosaic Life Care noted a number of risks that flow from an older work force, which means declining levels of strength and balance for many. Coupling that with age-related illnesses, he says, “that influences their tendency to be injured, as well as the type of care we can provide because we’re seeing more patients who have diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure.”

The biggest change in patient populations that Gaddy has seen in 21 years of practice is the extension of the outer age ranges for replacement surgeries. “When I came in, everybody was over 65 or close to 70; we rarely did a total joint on someone over 80.” Now, he says, “what I’m most impressed by is how many joint replacements I do on patients under 60 and over 80, even 85.”

And with that added life span comes increased incidence of joint failure, often requiring total replacement.

The concept hasn’t changed much in the nearly 80 years since the first total hip replacement, or nearly 50 years since the first total knee was swapped out: It’s trading out an organic ball-and-socket or hinge joint for one consisting of various elements such as metal, plastic and ceramic. What has changed, Weed said, is the process around a replacement.

“The emphasis is to have smaller and smaller incisions, with less and less disruption of the surrounding anatomy,” he said. “Minimally invasive stuff is the push right now.” That, he said, is leading to shorter hospital stays, and some physicians say those procedures might soon be done on an outpatient basis. “When I was a resident, a patient would stay in hospital for a week to 10 days,” Weed said. “Now, they

get out in two or three days.”

Lance Snyder, an orthopedic surgeon with Research Medical Center, said biologics are on the innovation forefront. “They’re not here yet, per se, but the injectables with biological agents are really gaining ground,” he said. That’s a process of using stem cells to produce material that can promote bone growth and even regenerate meniscus in a joint.

Recent years have seen increased use of hyaluronic acid to control pain, a big step in shorting the time for rehabilitation after injury or surgery, Snyder said, and platelet-rich plasma injected into tendons can help speed up recovery. “We have minimally-invasive joint preservation surgeries that we didn’t have 10 or 20 years ago to prevent arthritis and trying to regrow cartilage,” he said. And researchers are making headway on gene therapy to regenerate orthopedic tissues. “They’re not quite there; it’s not that individualized just yet, but they’re trying to move that way,” he said.

One key to making surgical innovation work, Reardon said, is post-operative pain reduction. “The less pain that’s caused to fix something, the better off that patient is in the long run, so we try to minimize the destruction of tissue,” he said. An ongoing revolution in pain-reduction will also lead to less use of narcotics after a procedure. “If a patient isn’t in pain, he can get up and walk in the recovery room even after a hip replacement,” Reardon said. “A lot of these used to require three or five days of hospitalization; now, it’s 12 to 24 hours and they can go home, and we know they do better at home than in a hospital.”

Templeton cited efforts to emphasize prevention, and research into ways to intervene before a patient develops reduced bone mass, or worse, osteoporosis. She’s hopeful that work in that field can benefit patients at the Veterans Administration Medical Center, where she also works. “Their quality of life is abysmal because of joint pain,” she said. “Is there a way to get to these patients before they reach this point, to regenerate cartilage?”

Renee Hollowell, a physical therapist for Olathe Health System, cited advances in robotic-assisted partial knee replacements, which she said have produced “spectacular” results. But from a therapy standpoint, professionals have developed a far greater understanding of pain and chronic pain. “If you graduated in physical therapy 20 years ago and never learned anything more, you’d only know about 10 percent of what we know today,” she said. Like Readon, she cited the vital role of pain reduction. “Muscle recovers a lot faster if you don’t have painful inhibition,” she said.

For an executive or business owner, the key to managing these health concerns starts with prevention, specialists say. That means a commitment to personal fitness, and it need not require huge chunks of time. “The executive may not have an hour to go to the gym every other day, but with 15 minutes here and 15 minutes there, they can benefit.” Snyder said. “Trainers can develop program they can do in a hotel room, they can bring exercise bands with them on the road, they can do push-ups in the room or walk 10 or 15 minutes around the hotel if they’re traveling.”

Bledsoe said it’s important to avoid risk factors that over time are likely to turn into other complications, like diabetes, obesity and activities that put additional wear and tear on joints. “And if you are seeing a doctor who seems to be encouraging you to use narcotic pain medications, especially if you’re not in that much pain, consider declining,” he said.

Templeton cautioned against Weekend Warrior syndrome, especially for those Type-A executives who don’t exercise regularly but want to compete on Saturdays. “You need consistency,” she said. Otherwise, the risk of injury increases substantially.

As for managing an older and more malady-prone staff at work, Bledsoe noted the challenges that employers have, being unable to mandate a fitness regimen for employees. “But they certainly can be aware of risk factors for injury in their company, they can take a greater interest in safety and ensuring that issues are addressed, that risks are addressed, so that employees are not injured,” he said.

Finally, Reardon urges more employers to embrace incentives that prompt employees to take more control over their own health. “That helps with workers compensation insurance and claims against a business,” he said. More broadly, though, “everybody’s health affects everybody,” Reardon said. “We’re not on island; whether its ebola in Africa or obesity in the U.S., a health problem in somebody else does affect the rest of us, and will continue to because we’re all in this together.”