HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

It’s a projection that must inspire night sweats for college recruitment executives in the Midwest: This region of the country, by 2021, can expect a 4 percent decline in the numbers of high school graduates it produced in 2009. The American South and West, by comparison, are anticipating sharply higher graduation totals: 8 percent in the South, 11 in the West. The East can expect a decline of only about 1 percentage point, according to figures from the National Center for Education Statistics.

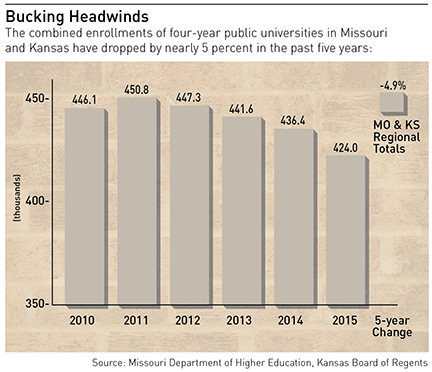

Those numbers are not coming at a good time for this region. Between 2010 and 2015, the total numbers of students enrolled at four-year institutions in Missouri and Kansas have essentially flat-lined, held in place by a 7 percent increase in the Show-Me State that offset a 5.4 percent loss in Kansas. (Community colleges have been much harder hit, with double-digit enrollment declines in each state, but that’s another story).

The University of Missouri’s comparative strength, however, may not endure: Following the campus protests that made national headlines in November and saw both the chancellor and system president resign, freshman enrollment applications have declined by 4.8 percent.

And all of that comes as universities nationwide are expanding their menus of on-line options. Which raises a question: Between demographics, dissent and distance learning, is the concept of a four-year education at some distant bastion of knowledge showing cracks at the foundation?

Not on your life, says John Jasinski, president of Northwest Missouri State University in Maryville. “There’s no question, there still remains a very strong value proposition for what we could call a traditional-based education, where students graduate from high school and come to live on college campuses,” Jasinski said. “Thirty years of research shows that graduates who come from high schools and live on campus become more engaged, and that’s where they find the most success. There’s still a large market for us. The trends in Missouri will keep declining among 18 year-olds until 2021-22, but nonetheless, we remain a great value proposition.”

Driving the two-state region’s growth has been the four-campus University of Missouri system, where combined enrollments over the past five years are up 8.56 percent. Missouri’s system’s star was University of Missouri-Rolla, up 23.3 percent as enrollment shot up from about 7,200 to nearly 8,900.

At Kansas State University, fall enrollment rose 2.14 percent over the five-year period, a significant improvement over the statewide total. That, said Pat Bosco, vice president for student life, reflects a strategic shift in Manhattan. “K-State has positioned itself as both a bricks and clicks type of school,” Bosco said. “We offer one of the most comprehensive distance-learning programs in America, but still have the classic college-town residential opportunity for thousands of students.”

A key to that, he said, is the town-and-gown relationship the university has with Manhattan, and the range of non-academic attractions—cultural, artistic, athletics—that make it a 24/7 environment and dispel the notion that a campus is in the middle of nowhere.

In 2012, the concern of administrators was that massive on-line open courses, or MOOCs, presented an emerging challenge to fixed-campus enrollments, offering specialized instruction from some top-tier academic instructors and institutions, and often, at no charge. But the MOOC model seems to have run into its natural limitations, educators say, and that’s likely to work in favor of college campuses.

“The experiments so far at using some of those to award credit at accredited universities have been unsuccessful,” said Holden Thorp, provost at Washington University in St. Louis. “The reason: there is still a lot of the experience of living on a campus and getting up and going to class and interacting informally with other students, faculty. The MOOCs have done a great job of proving how important that is. For those of us with residential facilities, that’s all to the good.”

Laurie DiPadova-Stocks, dean of the graduate school at Park University, says she’s not sure how long MOOC-style instruction will last, and suggests that it could morph into something else. The bigger issue, she says, is that “we are looking at democratization of education worldwide” and students are still discerning the value of the source of their instruction. “But I don’t see these as real classes, because there is no way a MOOC with 50,000 students can have that level of engagement that you’ll find in a brick-and-mortar classroom.”

Devon Cancilla, vice provost for online education at UMKC, said the context provided by a campus remained a key part of an institution’s value proposition. “People are recognizing that there are other ways to judge educational materials; there are all types of crowd-sourced activities and projects changing the way we look at it,” Cancilla said.

“But the analogy I use, from when I was in college, in the dorms, was that there was always that one student with the massive record collection, the cinder blocks and albums, where everybody would go to his room on a Friday and listen to this jazz, whether it’s Kansas City or New Orleans style, and that student was being an instructor of music in many ways, the person who said this is good or this is bad.

“It’s the same in education, where the faculty is helping you through that process.” That dynamic, he said, draws from other campus resources help students understand not just the subject matter itself, but to contextualize it.

Distance learning, enrollment demographics, instructional delivery innovation and other factors are all forces giving a new shape to the mission of universities, educators say. And for some, the campus structure can easily accommodate societal changes and still remain true to their longstanding missions and models.

“High school graduates today learn very differently than the way we did,” says Greg Gunderson, the new president at Park University. “We were the encyclopedia generation; today’s students are more Internet hummingbirds—they touch down, grab one piece of information, and they know a lot, but they learn differently and interact with data differently.”

They are also part of a changing work force that has demonstrated, already the value of lifelong learning. Work-force experts and projections from the U.S. Department of Labor suggest that nearly two-thirds of the jobs that will be available in 2030—when today’s schoolchildren have finished their college educations—don’t exist today. For those already out of school that means additional education will be required, and that’s an opportunity that campus officials are embracing.

“Educational models have to change,” said Gunderson, “Students now attend multiple educational models, and everyone in higher education has got to be more flexible because people are learning differently. We have to match the style of our students. It’s good that we offer certificates, it’s good that we have multiple modalities on-line, in person and blended environments, but we have to be responsive to meet the needs that allow them to maximize their education.”

There’s a lot riding on the success of those efforts by campus administrators, and not just for the campuses themselves, Jasinski noted.

“Think about the economic-development impact for communities; higher education is absolutely a driver of that,” he said. “We have an ED study from last year that showed Northwest Missouri State generated $617.5 million in added regional income. The ROI for the state on this is huge. We can’t lose the economic impact side of all this.”