HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

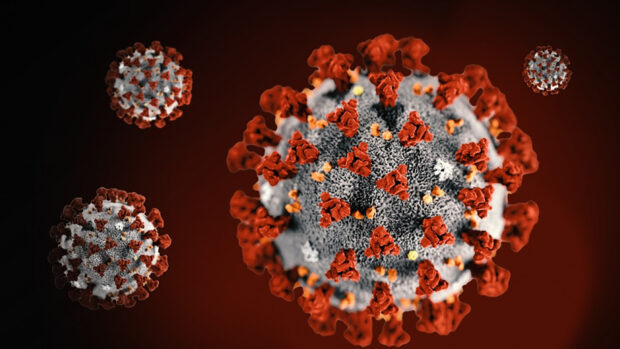

No matter what you call it--COVID-19, Coronvirus or Spawn of Satan--the pandemic of 2020 is getting worse. But while it's challenging, we're not unarmed in this fight.

Even if you’ve used his web site to find discounted electronics in the resale market, you might want to know a few things that Swappa.com’s Ben Edwards knows about employees working remotely.

Especially if you’re a business owner or manager who has been asked to pivot quickly and set people up to work at home in response to the coronavirus panic sweeping the nation. The company Edwards started as a bootstrapped side project 10 years ago now has 40 on the pay-roll—and no central office. His first hire, in fact, was a Swappa customer who began working from home in Ohio.

For many executives managing a crisis today, more remote work has been an unanticipated mandate or operating decision; for Edwards, it was simply the right strategic call with a startup pinched for funding, enabling to forgo the overhead costs of office space.

“For us, it was an issue of practicality,” Edwards says. “But as it transitioned from a project into a real business, we were still doing the majority of the work on-line. If you have the videoconferenc-ing, teleconferencing, email and all the right tools, you can do it.”

That should come as comfort to anyone uneasy with the thought of losing control and oversight by letting employees work from home. And having one less thing to worry about at this stage of a pandemic should come as welcome relief.

With an episode like this, where the dynamics change hourly regarding what’s known about the contagion, its spread, the treatment options for individuals, the financial impact on business and strain on the U.S. health-care system, what you think you know today is likely to be challenged by what you’ll know tomorrow.

Like everything else in business and life, the Covid-19 development is not happening in a vacuum. In the Midwest, in particular, concerns about its spread are unfolding against an economic backdrop framed by U.S. businesses’ relationships with their counterparts in, coincidentally enough, China.

One of those is the Trump administration’s slate of trade sanctions meant to punish China for a history of dumping of goods into U.S. markets, currency manipulation and state-sanctioned theft of intellectual property. That had already thrown global supply chains into disarray since the first tariffs were implemented in late 2018.

Another is the savage outbreak of swine flu in China that through the end of 2019 required destruction of roughly one-fourth of the world’s hog population—a development with huge implications, not all of them bad, for U.S. producers, packagers and distributors.

But since early December, when news began to surface of the first Covid-19 deaths in Wuhan, China, the virus has sparked an increasingly shrill level of news coverage and prompted public-health responses that critics argue are bordering on the extreme.

Overseas business and pleasure travel has been canceled wholesale, along with hotel bookings, college basketball tournaments, concerts and other large-scale public events. Even the South by Southwest conference and festivals were canceled, an estimated $348 million hit to the economy of Austin, Texas.

Yet interviews with experts in epidemiology, health-care delivery, bank-ing, business law, disease modeling and public-health organizations offer assurances that, while the outbreak should be taken seriously, it does not present a threat that justifies panic buying, fear-driven changes in investment strategies, product hoarding, or the kind of hyperventilating coverage that drives up ratings for the 24/7 news channels.

The takeaway from many of those experts is that if the virus is to truly be contained, top-down initiatives will never match the power of hundreds of millions of individuals’ acting in their own best interests to minimize their risk of exposure.

Despite considerable energy expended at every level of government—federal, state, county and municipality—to provide assurances to the public that “something is being done,” what’s been missing from much of the messaging is a sense of perspective on just what the world is dealing with.

From a purely actuarial perspective, Covid-19 had claimed 16,355 lives in the 15 weeks between the first fatality reported in China on Dec. 1 and mid-March. In that same span, roughly 15.7 million people died worldwide of other causes, including an estimated 4.9 million from cardiovascular disease, 2.76 million from cancer, and 389,000 from vehicle accidents alone. Even the flu has been a more prolific threat, with roughly 72,000 deaths in that span worldwide, 12,000 of them on average in the U.S.

That last statistic is particularly significant when you consider the underlying mathematics of disease modeling.

Majid Bani Yaghoub, chair of the math department at UMKC, has researched extensively on that topic. His assessment agrees with critics who say flu deaths can’t be directly compared to Covid-19 fatalities—the relationship between virulence and transmissibility changes the calculus, he said.

The common cold is far more likely to spread from one person to another; the flu less so; and Covid-19 even less so. But as those rates of transmission decline, the illnesses yield higher mortality rates. Historically, “that is the trade-off,” Bani Yaghoub said. But the increased lethality of Covid-19 is reshaping the way a threat like this is perceived.

Normally, a high-risk viral threat isn’t passed along with the kinds of frequency that health professionals are seeing right now. That is leading to unpredictability, and with so many unknown variables attached to this illness, public-health authorities are stuck between being perceived as over-reacting or, should the fatality rates spike, being accused of foot-dragging in the face of imminent threat.

It’s impossible to count the economic loss the Kansas City region incurred with cancellation of the Big XII basketball tournament’s games starting with the quarter-final round. Or the St. Patrick’s Day parade. Or any of dozens of other large-gathering events that have prompted organizers to throw in the towel for the spring of 2020.

Nationally, some estimates suggest a full 2 points could be shaved from GDP, which doesn’t have a lot of room to spare before you hit recessionary territory: the current estimate for 2019 is 2.1 percent.

By the third week of March, U.S. equities markets had lost more than a third of their value, and trillions in capitalization, since the Dow peaked just 450 points shy of 30,000 just four weeks earlier. Reports around the country reflect anxious executives pulling the plug on new hiring and, in some sectors, staff reductions.

For investors, said UMB Bank’s KC Mathews, there really is nowhere to run. “The safe harbor is the U.S. Treasury, which is why it’s down close to 1 percent,” he said, just days before the Fed reduced rates, putting the 10-year T-bill at barely more than 0.5 percent. “That’s about the lowest in history, and people are buying from all over the world.”

If there is good macro-economic news to be had, authorities say, it’s that production has started to ramp back up in China, where factory shutdowns began to pinch sup-ply chains in the U.S. “But the longer this goes,” Mathews said, “we’re going to get more and more buying” in perceived safe-harbor investments. That, he said, will mean that “Treasury stays low, and prices stay high.”

At CrossFirst Bank, CEO Mike Maddox noted the Fed’s rate cut and the market selloff and summarized: “It’s a crazy world right now.” He found himself with three extra days in Kansas City after organizers pulled the plug on a conference in San Diego. “That’s a hotel in San Diego that went from being full for three days to being empty. That’s just one ex-ample of a lot of different industries that might be feeling the impact.”

But it’s not the only threat, he noted. As the viral death toll in the U.S. was starting to inch up, Russia and Saudi Arabia took off the gloves and started a full-scale oil price war after being unable to resolve differences over output targets that would stabilize prices. Almost immediately, oil fell 20 percent on spot markets, adding additional fuel to the market selloff.

“You’re seeing low commodity prices and the oil and gas industry now, with oil well under $50 a barrel,” Maddox said. “When the oil starts getting down into the mid-to-low $40 range, you’re going to start seeing stress on lenders who have exposure to the oil and gas industry.”

Within a week, North Sea Brent Crude was down to near $35, and West Texas Intermediate had plunged to $30.50 a barrel.

Fang Shen, a partner at Husch Blackwell whose work includes international transactions, brings an additional perspective to the crisis as president of the Asian American Chamber of Commerce in Kansas City.

“A number of our member businesses are either involved in global trade or with some sort of international supply chain. We’ve seen a lot of interruption” there since the first reported Covid-19 death in China on Dec. 1.

With the firm, she said, “the first week or two, there was not a lot of impact, but more recently, more clients are inquiring at the strategy level, anticipating interruption in their supply chain, or as some kind of legal strategy, whether production delays will be allowed or not. From those, we know a lot of businesses are seeing interruption or delay.”

That, she said, is happening across business sectors. And in the Midwest, Shen said, “we have more businesses in the manufacture of machinery, and we’re definitely seeing that sector hurt, but it’s certainly not limited to that.”

With the supply interruptions, coming on top of cost issues associated with the trade disputes between the U.S. and China, Shen said, “we definitely saw some American businesses starting to shift supply strategies to alternative countries, but still outside the U.S. a number are moving production to countries like Vietnam and diversifying their chains.”

The challenge for everybody right now, she said, “are all of the unknowns and whether the measures being taken right now are the correct ones.”

None of that is escaping the attention of state economic-development officials.

. “We’re seeing what’s happening in the global economy and we’re watching the markets like everybody else,” said Rob Dixon, director of the Missouri Department of Economic Development. “But from our perspective, the fundamentals of the economy are intact. This is not 2008, it’s not a Great Recession with a broken economy that was fundamentally problematic.”

In the short term, he said, “clearly the economy is responding to this crisis, but this is not a structural problem with the economy.” State officials, he said, were in increased communication with each other to assess the need for any additional action, and were working with health officials to ensure greater preparation if caseloads spike.

After that? “When the situation resolves,” Dixon said, “I think we’ll be back on track with the economy going in the direction it had been heading.”

As for companies that are trying to minimize staff exposure by having more employees work remotely, Swappa’s Edwards offered some guidance: “A big part of making it work is choosing the tools you expect the team to use while working from home,” he said.

“Document-sharing, a lot of things can be accomplished by email, and with the in-person meeting replacement, luckily there are lots of solutions for that.”

But there are operational considerations as well, he said. “You want to know what the office routine looks like—does that change because people are not at the office? There might be parts of it that aren’t scheduled, but just sort of happen around the same time every day because it’s part of the culture. Those are processes that might need to be formally scheduled because not everyone is there now,” he said.

Employees who find themselves available for work earlier, for example, after dropping the kids off at school and getting back home, might want to clock out earlier at days’ end, Edwards noted. That, too, will need to be adjusted to fit existing operating deadlines.

“It’s really about establishing a new routine,” he said. “I can imagine it would be a significant challenge to abruptly adopt a remote work flow. It’s possible, but it’s going to be a challenge.”

It may not meet the definition of sleep deprivation–yet–but medical staff members and administrators at area hospitals are definitely getting extra hours in over the past two weeks, trying to stay ahead of a potential epidemic that might not fully emerge.

Dana Hawkinson, an infectious-disease specialist for the University of Kansas Health System, noted that while the Covid-19 phenomenon may be a new scientific development, the idea of preparation for mass illness isn’t.

“We’ve had protocols for things like this in place for years,” he said during a news conference live-streamed on the health system’s Twitter feed.

He was joined by Steven Stites, vice president for clinical affairs, and they jointly stressed the message that not ev-eryone would be susceptible to the same level of harm from Covid-19. People older than 60, especially, and those with complicating conditions like hypertension, diabetes or cardiovascular disease, should take extra precautions to avoid large gatherings of people, and should be focused on things like frequent hand-washing with hot water and cleaning solutions of at least 60 percent alcohol content, and avoiding contact with others if you’re experiencing symptoms yourself.

HCA Healthcare, the nation’s largest hospital system, has marshaled the resources of nearly 215 hospitals to provide federal officials with more immediate data on patterns of fever concentrations and white blood cell data across the country.

Inside those facilities nationwide, many of the same strategies are being used with Covid-19 that are brought to bear during flu outbreaks: Patients with unexplained respiratory conditions will be channeled away from the rest, just as sick children at a pediatrician’s office are directed to separate waiting rooms.

Lee Norman, a former colleague of Hawkinson and Stites’ who is now secretary of the Kansas Department of Health and Environment, used that news conference to address the challenges of trying to reverse-engineer the contact lists of people suspected of being infected.

In just one example, he said, a single patient who ultimately tested negative generated a list of more than 400 contacts. That’s the level of challenge facing state officials trying to track the spread of the illness.

Given that, Norman said, “you have to own your own preparedness. I suspect we will have community spread with this. We need everyone to be socially responsible to the public and to themselves” to help combat the spread of the illness and keep it contained.