HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

December 2021

Mark 12:41-44, the tale of the widow making a charitable offering of all she had—two copper coins—instructs us in the relative value of giving from one’s poverty, as opposed to gifts made from one’s wealth.

It’s certainly a message to keep in mind as we consider the events of 2020 and 2021 and their impact on businesses. Tens of thousands of small-company owners who were anticipating a prosperous year 24 months ago are, in fact, no longer in business.

And some well-known names in big business are gone, as well.

Given that, it’s probably no surprise that estimates of philanthropy in the United States showed a double-digit decline in corporate giving last year. On some levels, it’s surprising that the drop-off was only about 6 percent, according to Giving USA.

And yet, American companies, large and small, still had the wherewithal to pony up nearly $16.9 billion for charity and non-profit work.

Add that to the nearly $41.2 billion contributed by individuals, and you have a level of sharing that—again—reinforces the claim the United States has to the title of World’s Most Philanthropic Country.

Providing local lift for those contributions by companies are this year’s Corporate Champions: BKD, LLP, Cerner Corp., the Kansas City Board of Public Utilities, Lathrop GPM, Security Benefit Corp., and Summit Homes

In their stories, you will see how the leadership of these organizations combined strategy and sympathy to create a synergy of caring. They offer inspiration and guidance to those who would return to this community a measure of the blessings they—and thousands of their employees—have harvested.

Wyandotte County isn’t the poorest of Kansas’ 105 counties—but it’s not far from that distinction: A greater share of students in the Kansas City, Kan., school district live in poverty than any other in the state. So take Bill Johnson at his word when the CEO of the Board of Public Utilities says: “There is much need.” But, he says, there is also tremendous community, pride, growth, and opportunity. His publicly owned utility aims to boost all three. So the BPU employs a broad strategy that incorporates fund-raising through events like its annual golf tournament, giving through its employee foundation, back-to-school fairs, holiday-related fundraisers, and more, all part of a three-pronged approach that includes donations and sponsorships, volunteerism and environmental stewardship. The golf tournament is a special point of pride, having raised $680,000 since its inception to benefit youth-focused organizations like KVC Health Systems, KCK West Kiwanis, and others that feed children, encourage reading or purchase equipment for them, Johnson says. Through employee direct donations and BPU’s matching gifts, another $200,000 is raised annually. And the hardship-assistance program helps offset $120,000 in consumer utility costs. Employees generate 5,000 volunteer hours a year, benefiting an estimated 6,000 students, and also gather toys for underprivileged children, gather back-to-school supplies and provide Thanksgiving meals to needy families. On top of that, they have a robust board-engagement history of service. “As a non-

profit, public utility, BPU is customer-owned.” Johnson notes. “We measure ourselves by how much money stays in the community, how we can provide reliable/dependable power and water, and the obligation we have to help our neighbors” Because all of its employees live and work in Wyandotte County, he says, “we recognize that our efforts to improve, better and assist our community lifts up all—benefits all—and WyCo continues to make tremendous progress. They play, shop, dine, and raise their families in the same community they as public servants serve. WyCo has a tremendous sense of community pride, working together and being unified—and this sense of being a ‘Dotte’ easily rolls over to our employees, who know they are either working, or donating volunteer time or making a difference to benefit their neighbors and others they live alongside.”

In numbers of CPAs, the accounting-consulting firm BKD, LLP is the leader in the Kansas City area. But that leadership is also on display with the firm’s commitment to non-profit work—perhaps most impressive with the way the partners there have rallied to one particular cause: The United Way’s Tocqueville Society. Membership in this elite group of donors isn’t cheap, at $10,000. Per year. Yet virtually all of the more than two dozen partners in the office here in KC is meeting that noble standard. The Society, says managing partner Rachel Dwiggins, resonates with BKD’s giving culture, “so it’s no wonder that our partners are highly engaged with it. It’s been a key part of our community involvement since the local Tocqueville chapter was formed in the 1980s.” BKD’s leadership here, she says, “commits to significant annual contributions because we understand that our charitable community needs reliable funding year-after-year. The Tocqueville Society membership and its Step Up program are built directly into our annual giving campaign.” It’s but one plank in a corporate philanthropic platform that includes planned giving, special-needs fundraising for causes like COVID-19 relief, board engagement by employees, corporate matches of employee charitable giving, and more. “BKD’s philanthropic culture runs so deep that it’s difficult to put into historical perspective,” Dwiggins says. “We’ve been active in supporting Kansas City’s charitable organizations since our founding in 1923. We not only give financially, but also encourage our people to give back to the community through volunteering and board membership.” A powerful arm of that philanthropy is the BKD Foundation, which steers charitable contributions to a wide variety of area organizations, particularly through the United Way of Greater Kansas City. Its work with the United Way since the start of the pandemic has yielded more than $460,000 in three campaigns. Firm-wide, the foundation has made more than $19 million in charitable contributions since its creation in 2000, Dwiggins says, including more than $3.5 million in the current fiscal year. And with offices across much of the nation, the Springfield-based company provides a measure of local autonomy by allowing each local practice’s foundation committee to steer the local giving.

In numbers of CPAs, the accounting-consulting firm BKD, LLP is the leader in the Kansas City area. But that leadership is also on display with the firm’s commitment to non-profit work—perhaps most impressive with the way the partners there have rallied to one particular cause: The United Way’s Tocqueville Society. Membership in this elite group of donors isn’t cheap, at $10,000. Per year. Yet virtually all of the more than two dozen partners in the office here in KC is meeting that noble standard. The Society, says managing partner Rachel Dwiggins, resonates with BKD’s giving culture, “so it’s no wonder that our partners are highly engaged with it. It’s been a key part of our community involvement since the local Tocqueville chapter was formed in the 1980s.” BKD’s leadership here, she says, “commits to significant annual contributions because we understand that our charitable community needs reliable funding year-after-year. The Tocqueville Society membership and its Step Up program are built directly into our annual giving campaign.” It’s but one plank in a corporate philanthropic platform that includes planned giving, special-needs fundraising for causes like COVID-19 relief, board engagement by employees, corporate matches of employee charitable giving, and more. “BKD’s philanthropic culture runs so deep that it’s difficult to put into historical perspective,” Dwiggins says. “We’ve been active in supporting Kansas City’s charitable organizations since our founding in 1923. We not only give financially, but also encourage our people to give back to the community through volunteering and board membership.” A powerful arm of that philanthropy is the BKD Foundation, which steers charitable contributions to a wide variety of area organizations, particularly through the United Way of Greater Kansas City. Its work with the United Way since the start of the pandemic has yielded more than $460,000 in three campaigns. Firm-wide, the foundation has made more than $19 million in charitable contributions since its creation in 2000, Dwiggins says, including more than $3.5 million in the current fiscal year. And with offices across much of the nation, the Springfield-based company provides a measure of local autonomy by allowing each local practice’s foundation committee to steer the local giving.

For all the financial muscle that can be flexed with 400 lawyers practicing in 14 office nationwide—and it’s a lot—arguably the greatest contributions made at Lathrop GPM involve the hours that are not billable: the firm’s pro bono work, something foundational to the firm’s values. “Lathrop GPM considers pro bono legal service a professional responsibility and a community obligation of the firm,” says Kansas City office managing partner Jean Paul Bradshaw. “We believe the privilege of practicing law comes with a responsibility to ensure that everyone has access to the legal system, regardless of resources. We take pride in using our legal skills to help people in need and are honored to work with legal service organizations and non-profits in each of our office locations to represent the most vulnerable among us.” They advocate for the innocence of the wrongly convicted, and cases in immigration, housing, veterans and child advocacy. “Pro bono work gives our attorneys a stronger sense of purpose, enhances the skills of our more junior attorneys, and creates stronger bonds with their community,” Bradshaw says. “The unprecedented events of the last two years have amplified the needs in our communities. They also shed light on the barriers many face when approaching the legal system. As lawyers, we are equipped to tackle those barriers and help those who need us most.” That all flows from a historical approach to service that has long been a core value of the firm. “Through active involvement in charitable organizations, our attorneys and staff strive to make a positive difference in both local and national communities,” Bradshaw says. Another pillar of its strategy is support for organizations that are important to the firm’s clients. “With our recent combination to form Lathrop GPM, we introduced the Lathrop GPM Foundation in April 2020, a separate entity from the firm, which works with our attorneys and staff to strengthen the communities where we live and work through grant-making and volunteerism,” he said. “The foundation makes strategic investments in initiatives that contribute to the welfare of our communities, with emphasis on increasing access to justice and legal services.”

For all the financial muscle that can be flexed with 400 lawyers practicing in 14 office nationwide—and it’s a lot—arguably the greatest contributions made at Lathrop GPM involve the hours that are not billable: the firm’s pro bono work, something foundational to the firm’s values. “Lathrop GPM considers pro bono legal service a professional responsibility and a community obligation of the firm,” says Kansas City office managing partner Jean Paul Bradshaw. “We believe the privilege of practicing law comes with a responsibility to ensure that everyone has access to the legal system, regardless of resources. We take pride in using our legal skills to help people in need and are honored to work with legal service organizations and non-profits in each of our office locations to represent the most vulnerable among us.” They advocate for the innocence of the wrongly convicted, and cases in immigration, housing, veterans and child advocacy. “Pro bono work gives our attorneys a stronger sense of purpose, enhances the skills of our more junior attorneys, and creates stronger bonds with their community,” Bradshaw says. “The unprecedented events of the last two years have amplified the needs in our communities. They also shed light on the barriers many face when approaching the legal system. As lawyers, we are equipped to tackle those barriers and help those who need us most.” That all flows from a historical approach to service that has long been a core value of the firm. “Through active involvement in charitable organizations, our attorneys and staff strive to make a positive difference in both local and national communities,” Bradshaw says. Another pillar of its strategy is support for organizations that are important to the firm’s clients. “With our recent combination to form Lathrop GPM, we introduced the Lathrop GPM Foundation in April 2020, a separate entity from the firm, which works with our attorneys and staff to strengthen the communities where we live and work through grant-making and volunteerism,” he said. “The foundation makes strategic investments in initiatives that contribute to the welfare of our communities, with emphasis on increasing access to justice and legal services.”

How does a global health-care IT company, with 23,000 employees and dozens of offices around the world craft a cohesive corporate philanthropic strategy? With focus. And in the case of Cerner Corp., the region’s largest private-sector employer, that focus is a weave of three philanthropic threads: health, home and heroes. “We are continuing our focus on providing equitable access to health care for children through grants and wellness programming, honing in on initiatives to reduce disparities and volunteerism to improve our global communities, and supporting our health-care industry and non-profit partners through strategic grants and initiatives,” says Shanna Adamic, executive director of the Cerner Charitable Foundation, the company’s philanthropic arm. Those areas of emphasis produce health-focused programming in 235 schools in this region, financial support for local health-care community non-profits, and promoting Cerner associate volunteerism throughout the city, Adamic says. Rebranded over the past year from the First Hand Foundation brand, it oversees medical grants and school programs supported by Cerner associates, sponsors and community supporters. “Each year, because of their generosity, we invest approximately $2.5 million to life-changing and life-saving medical grants for children worldwide and nearly $1 million to school programs impacting the health and wellness of our students right here in Kansas City,” Adamic says. The decision of where the grants go is decided on by a 30-member associate-led Clinical Decision Committee to ensure good stewardship of donated dollars. For a company that hires thousands, one challenge is integrating new employees into that culture of giving. Cerner’s philanthropic vision, Adamic says, “is one of the first things our new associates learn about in orientation. It is embedded in our culture at the executive level and shared throughout the company. I personally believe that when done right, a philanthropic spirit naturally resonates, like when a pebble hits water, throughout a company. I believe it is done right at Cerner. Cerner is not just a company that is “in” health care—it is a global team of people who care about the future of health care and, quite honestly, their communities. That includes our very own beautiful Kansas City. We are proud to be Corporate Champions in philanthropy and look forward to continuing to strive toward healthier tomorrows and strengthening this community.”

How does a global health-care IT company, with 23,000 employees and dozens of offices around the world craft a cohesive corporate philanthropic strategy? With focus. And in the case of Cerner Corp., the region’s largest private-sector employer, that focus is a weave of three philanthropic threads: health, home and heroes. “We are continuing our focus on providing equitable access to health care for children through grants and wellness programming, honing in on initiatives to reduce disparities and volunteerism to improve our global communities, and supporting our health-care industry and non-profit partners through strategic grants and initiatives,” says Shanna Adamic, executive director of the Cerner Charitable Foundation, the company’s philanthropic arm. Those areas of emphasis produce health-focused programming in 235 schools in this region, financial support for local health-care community non-profits, and promoting Cerner associate volunteerism throughout the city, Adamic says. Rebranded over the past year from the First Hand Foundation brand, it oversees medical grants and school programs supported by Cerner associates, sponsors and community supporters. “Each year, because of their generosity, we invest approximately $2.5 million to life-changing and life-saving medical grants for children worldwide and nearly $1 million to school programs impacting the health and wellness of our students right here in Kansas City,” Adamic says. The decision of where the grants go is decided on by a 30-member associate-led Clinical Decision Committee to ensure good stewardship of donated dollars. For a company that hires thousands, one challenge is integrating new employees into that culture of giving. Cerner’s philanthropic vision, Adamic says, “is one of the first things our new associates learn about in orientation. It is embedded in our culture at the executive level and shared throughout the company. I personally believe that when done right, a philanthropic spirit naturally resonates, like when a pebble hits water, throughout a company. I believe it is done right at Cerner. Cerner is not just a company that is “in” health care—it is a global team of people who care about the future of health care and, quite honestly, their communities. That includes our very own beautiful Kansas City. We are proud to be Corporate Champions in philanthropy and look forward to continuing to strive toward healthier tomorrows and strengthening this community.”

It’s one of the region’s largest private companies today, but it started out in 1892 with a whopping $11 in capital pooled by Topekans. Even then, the goal was philanthropic: creating an insurance fund for those who otherwise couldn’t afford it. “This promise that our founders made has remained embedded in our culture ever since,” says Security Benefit CEO Mike Kiley. “Today, it has evolved to cover more than 100 organizations that serve low-income and at-risk individuals, promote education, health, and the arts, and support diversity initiatives. When he came to that role in 2010, Security Benefit was a long way from being an industry leader in retirement services. But he understood immediately the tie between organization and community. “It was clear that Security Benefit meant something to the people of Topeka, that the firm was part of the city’s history. We wanted to preserve that by not only maintaining our giving, but expanding on it, and by rebuilding the company into the industry leader it is today.” It was important, he says, to maintain the legacy of the firm and show partners, employees, and neighbors “that Security Benefit wasn’t just going to survive, it was going to thrive. And with it, we were going to be there to help Topeka and its community organizations thrive too. We gave our more than 1,000 associates the opportunity to step up, and they did.” That has come from a focus on identifying need, then blending efforts across areas of giving to achieve impact on issues most relevant within the community: education, health, the arts, and even local law enforcement. The firm has created a charitable trust committee—comprising volunteers from multiple departments—that has oversight of giving, and that manages the annual fund. They meet monthly to review every organization and every request, and they coordinate with HR and senior management to keep them informed. When it comes to giving, it’s important to challenge the status quo, Kiley says, and “it’s in our DNA. In turning around Security Benefit, we had to question a lot about how insurance companies were run. The same is true with our approach to philanthropy: While we seek to attract, retain, and motivate groups of diverse, talented individuals, one thing we all have in common is the tendency to question why things are done a certain way and how we could go about making them better. It’s part of our legacy, one we’re proud of and determined to preserve.”

It’s one of the region’s largest private companies today, but it started out in 1892 with a whopping $11 in capital pooled by Topekans. Even then, the goal was philanthropic: creating an insurance fund for those who otherwise couldn’t afford it. “This promise that our founders made has remained embedded in our culture ever since,” says Security Benefit CEO Mike Kiley. “Today, it has evolved to cover more than 100 organizations that serve low-income and at-risk individuals, promote education, health, and the arts, and support diversity initiatives. When he came to that role in 2010, Security Benefit was a long way from being an industry leader in retirement services. But he understood immediately the tie between organization and community. “It was clear that Security Benefit meant something to the people of Topeka, that the firm was part of the city’s history. We wanted to preserve that by not only maintaining our giving, but expanding on it, and by rebuilding the company into the industry leader it is today.” It was important, he says, to maintain the legacy of the firm and show partners, employees, and neighbors “that Security Benefit wasn’t just going to survive, it was going to thrive. And with it, we were going to be there to help Topeka and its community organizations thrive too. We gave our more than 1,000 associates the opportunity to step up, and they did.” That has come from a focus on identifying need, then blending efforts across areas of giving to achieve impact on issues most relevant within the community: education, health, the arts, and even local law enforcement. The firm has created a charitable trust committee—comprising volunteers from multiple departments—that has oversight of giving, and that manages the annual fund. They meet monthly to review every organization and every request, and they coordinate with HR and senior management to keep them informed. When it comes to giving, it’s important to challenge the status quo, Kiley says, and “it’s in our DNA. In turning around Security Benefit, we had to question a lot about how insurance companies were run. The same is true with our approach to philanthropy: While we seek to attract, retain, and motivate groups of diverse, talented individuals, one thing we all have in common is the tendency to question why things are done a certain way and how we could go about making them better. It’s part of our legacy, one we’re proud of and determined to preserve.”

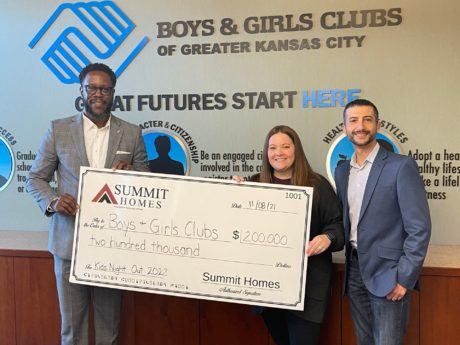

From something as simple as an ask, a deeper corporate philanthropic strategy can sprout. Thus was the case with Summit Homes back in 2011, when St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital came calling. “That got us more focused on just how powerful our position as a business leader in the community could translate into making a marked difference for those in need,” says Summit Homes’ CEO, Fred Delibero. The hospital wanted to know if Summit would build the St. Jude Dream Home in Kansas City for 2012. “That’s when we began to step up our ability to drive progress positively impacting our community,” Delibero says. “Together with our trade partners, we raised millions of dollars over the next few years benefiting the patients at St. Jude.” But the good works didn’t stop with homes built for that fund-raiser each year since “Our interest in charitable giving evolved into forming a charitable giving committee comprising business leaders and team members elected each year by their peers,” Delibero says. “We also made a commitment to donate a fixed percentage of our net revenue, and the first charitable giving committee defined the parameters in which we would consider getting involved with an organization.” Among those: a commitment to help children, families with children, those that are unable to help themselves, animals and to support diversity. “We also agreed that we wanted to not only give but be involved lending our business expertise and the efforts of our team members to enhance the organizations we support,” Delibero says. The sale to Clayton Homes in 2016 further cemented that giving strategy, he says, and that philanthropy aligned with Summit’s can-do approach to giving, even in times of construction-sector challenges with costs of materials, shortages, and tight labor. “Honestly, we don’t let anything stop us from achieving our goals,” Delibero says. That pays off for groups like Harvesters, the Drumm Farm Center for Children, Boys & Girls Club of Greater Kansas City, Hope Haven of Cass County, Wayside Waifs and Heartland Men’s Chorus, to name a few. For his staff, he says, “the key is providing a variety of ways for team members to get involved and communicating with our team about the ways collectively we’re impacting our community. … Many new team members come aboard with a giving mindset. Culturally, we hire humble people, and our values align with their values.“

From something as simple as an ask, a deeper corporate philanthropic strategy can sprout. Thus was the case with Summit Homes back in 2011, when St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital came calling. “That got us more focused on just how powerful our position as a business leader in the community could translate into making a marked difference for those in need,” says Summit Homes’ CEO, Fred Delibero. The hospital wanted to know if Summit would build the St. Jude Dream Home in Kansas City for 2012. “That’s when we began to step up our ability to drive progress positively impacting our community,” Delibero says. “Together with our trade partners, we raised millions of dollars over the next few years benefiting the patients at St. Jude.” But the good works didn’t stop with homes built for that fund-raiser each year since “Our interest in charitable giving evolved into forming a charitable giving committee comprising business leaders and team members elected each year by their peers,” Delibero says. “We also made a commitment to donate a fixed percentage of our net revenue, and the first charitable giving committee defined the parameters in which we would consider getting involved with an organization.” Among those: a commitment to help children, families with children, those that are unable to help themselves, animals and to support diversity. “We also agreed that we wanted to not only give but be involved lending our business expertise and the efforts of our team members to enhance the organizations we support,” Delibero says. The sale to Clayton Homes in 2016 further cemented that giving strategy, he says, and that philanthropy aligned with Summit’s can-do approach to giving, even in times of construction-sector challenges with costs of materials, shortages, and tight labor. “Honestly, we don’t let anything stop us from achieving our goals,” Delibero says. That pays off for groups like Harvesters, the Drumm Farm Center for Children, Boys & Girls Club of Greater Kansas City, Hope Haven of Cass County, Wayside Waifs and Heartland Men’s Chorus, to name a few. For his staff, he says, “the key is providing a variety of ways for team members to get involved and communicating with our team about the ways collectively we’re impacting our community. … Many new team members come aboard with a giving mindset. Culturally, we hire humble people, and our values align with their values.“