HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

(Seated, left to right) Teresa Martin, Lockton Companies; Susan McGreevy, Stinson Leonard Street; Adrienne Haynes, Blue Hills Community Svc.; Jeff Werthmann, Turner Construction; Joe Mabin, Minority Contractors Association; Tony Privitera, Mark One Electric; Wells Haren, HarenLaughlin Construction; Alise Martiny, Greater Kansas City Building & Construction Trades Council (Co-Chair) (Back row, left to right) Joe Sweeney, Ingram’s Magazine (Moderator); Greg Harrelson, Fogel-Anderson Construction; Mike Campo, Lockton Companies; Courtney Kounkel, Centric Projects; Bill Fagan, Design Mechanical; Dirk Schafer, JE Dunn Construction; Shawn Burnum, Performance Contracting Group; Sheila Ohrenberg, Sorella Group; Mary McNamara, Cornell Roofing & Sheet Metal; Bill Prelogar, NSPJ Architects; Steve Buche, Neighbors Construction; Richard Bruce, Builders’ Association; Chris Vaeth, McCownGordon Construction; Scott Kelly, Kelly Construction; Don Greenwell, Builders’ Association (Co-Chair); Mark Heit, McCarthy Construction; Tim Moormeier, U.S. Engineering.

A generally upbeat tone marked Ingram’s 2015 Construction Trades Industry Outlook assembly on May 15 at the Builders’ Association’s Education and Training Center in North Kansas City. More than 25 executives from the construction world and its related disciplines gathered to assess current events in their sector, ranging from changes in staffing, to financing and the balance of negotiated work versus bid work.

But there remained an air of uncertainty, over where new cohorts of workers would come from, how future generations would be recruited to the field, what changes are being wrought in the workplace by demography, and challenges in succession planning for family owned firms, for starters.

Co-chairs and co-sponsors Don Greenwell of the host Builders’ Association and Alise Martiny of the Greater Kansas City Building and Construction Trades Council led an energetic, informative two-hour discussion that reinforced just how vital the sector is to regional business overall.

Labor Shortage or Not?

In the opening round, Don Greenwell noted the prevalence of questions about work-force challenges in his role with the Builders’ Association. “The work-force issue is the one that comes up most frequently”, he said of his interactions with contractors. A similar forum in Springfield earlier in the month produced a 2½ hour discussion, and nearly all of it was focused on work-force issues, he said.

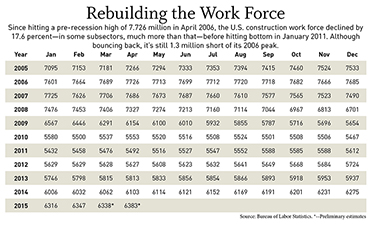

“I am starting to see a labor shortage, especially in the basic trades,” said Alise Martiny. But, she sees the tight labor market as a great opportunity to bring skilled workers on board. It’s becoming a bigger issue, she said, since the downturn began in 2007. “They’ve gone to other areas, or we haven’t trained or recruited new individuals because there hasn’t been sustainability to work the 1,500-1,600 hours normally worked” in the sector each year.

Wells Haren, president of Haren-Laughlin Construction, feels the labor shortage right now, especially with the company’s heavy involvement in the red-hot multi-family housing sector. “Labor shortage is a huge issue for us, primarily in the carpentry trades, framing and drywall,” Haren said. “The Association of General Contractors has seen this coming for decades, and I think it will get a little bit worse before it gets better.”

Ditto, said Steve Buche, vice president at Neighbors Construction, a market leader in multifamily construction, which he believes is reaching a market peak in the Kansas City area. Still, he said, “we’re having a lot of trouble with enough labor force to meet the needs of the multifamily industry. … I think it’s affecting the quality, the lead times, the schedules on the jobs and everything on down the line.”

Sheila Ohrenberg, president of both the Sorella Group Specialty Contractors and the local chapter of the American Subcontractors Association, said her bigger concern was not with the trade specialists but with general contractors office management, where demand is creating turnover that smaller firms can’t compete with.

Mary McNamara, owner of Cornell Roofing and Sheet Metal, concurred, saying the shortage is also being felt at

the on-site project management level. “We’re putting in as many training programs and as much money as our company can put in,” she said. A particular challenge is communications skills for those who have to manage on-site employees for the first time; the skill set just isn’t there.

At Mark One Electric, vice president Tony Privitera doesn’t see a shortage, and he credits the work of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers for attracting and training new workers through innovative programs. “It allows us to compete in the residential market as a union contractor,” he said.

Adrienne Haynes, the incubator manager for Blue Hills Community Services, said she was hearing questions about the lack of qualified construction workers. Contractors or subs may put out a job posting and get 200 applications, she said, “but the number of people who can perform the job without being hand-held” is comparatively small.

Bigger Shortage Coming

Dirk Schafer, Midwest regional president for JE Dunn Construction, saw things differently. “We’re not quite in a labor shortage, but I think it’s coming,” he said.

Tim Moormeier, president of U.S. Engineering, agreed. “There is no shortage in Kansas City; we don’t seem to have trouble manning projects in town. We are finding it’s more difficult in surrounding areas,” particularly in rural areas, he said.

That’s the way McCarthy Building Cos.’ Mark Heit, vice president of operations, sees things. “If you step back and remove yourself from Kansas City, we see spots around the country, where we have difficulty finding a trained, educated labor force,” he said, and it’s a bigger issue in some subsectors, such as solar, than in others, and varies from market to market.

Shawn Burnum, regional manager for Performance Contracting Group, said the company “hasn’t been hit by a manpower shortage in Kansas City yet, “but it’s quickly on the horizon if all the buildings everybody is talking about do actually come forward.”

“I would reiterate what a lot of people said that in Kansas City, we don’t see the labor shortage that much,” said Jeff Werthmann, operations manager for Turner Construction Co.. “But I cover seven states and we have a significant shortage in Des Moines and Denver.” Case in point: A 48-hour break in work over a contract dispute involving the new VA hospital in Denver saw 1,400 workers scatter to the winds before the issue was resolved. Four months later, “we haven’t got labor on that back up to 600 yet,” Werthmann said. “Seven hundred workers disappeared in two days, and they’re all working somewhere else now.”

At Design Mechanical, which works with a large cohort of sheet-metal workers and pipefitters, “the consensus is that we will start shrinking and there will be some shortage down the road if times keep getting better,” said Bill Fagan, customer accounts manager. That will be a problem because in recent years, many building owners have deferred maintenance on big-ticket projects, and that will catch up to them at the wrong time, especially on work that is more technical in nature. “We are seeing a shortage on the highly technical side of the business,” Fagan said.

Ancillary Effects

Away from construction boardrooms and job sites, the changes are showing up, as well. Richard Bruce, education training director for the Builders’ Association, noted that assembly participants were sitting in one piece of the puzzle—the education center, where 924 people are going through apprenticeship training in nearly a dozen trades. “We’re trying to solve a lot of these problems,” he assured others at the table.

Bill Prelogar, principal architect with NSPJ Architects, noted that his sector was ramping up several years ago in anticipation of the Builders’ current good times. “When multifamily started getting hot about five years ago and other kinds of projects were still in the doldrums, we were able to start hiring up young architects quite readily and were able to pick off about 6-8-10 people who were coming out of school at the very top of their classes.” NSPJ still has no trouble landing students from the tops of their classes.

Joe Mabin, of the Minority Contractors Association of Greater Kansas City, pointed out that “no one has mentioned that a lot of the people we lost during the downturn aren’t coming back.” Coupled with retirements in the sector, he said, “I see a shortage with the complaints I get from my members, specially for women and minorities. … When it rains on workers in general,” Mabin said, “it floods on minorities and women.”

“I see the problem on the back end,” said Susan McGreevy, a construction lawyer for Stinson Leonard Street. Huge demand for subcontractors means they are substituting personnel on current job sites to secure additional work, and in some cases, “the sub gets a new job he likes better and he just walks off” of a construction site.

Teresa Martin, a partner with Lockton Companies, said the insurance broker was seeing more clients concerned about the ability of subcontractors to perform. “Everybody is concerned about it, they see it coming,” she said of a broader labor shortage. But they are also concerned about retention as competition for skilled labor and project managers heats up.

Her colleague Mike Campo, a Lock-ton team leader, said that in the southeast and north central parts of the country, “we hear horror stories. We hear wage inflation. We hear jobs being delayed substantially.” In one case where a tornado hit a job site, “they couldn’t get their workers back even with just one or two days’ downtime, because they got more money to go down the street.” Kansas City is in an insulated situation, he said, “But our clients, like everyone else here, say it’s coming.”

Quantity vs. Quality

Chris Vaeth, director of preconstruction for McCownGordon Construction, addressed the issue of work-force qualifications. “It’s not so much do you have a warm body, it’s the skill set they have,” he said. “Manpower and skill set are two very different things.”

Shortage, said Courtney Kounkel, a partner at Centric Projects, “depends on what size market you’re in. I think the larger subs or trade subs fared better than the smaller, and a lot of those went out of market during the downturn,” she said, noting that larger firms were able to retain qualified workers. “We’re seeing new sprouts of companies, which is great, and we want to support them, like others supported us when we started five years ago, but we’re seeing quality issues with some of those companies that are starting up and haven’t had the training.”

Greg Harrelson, president of Fogel-Anderson Construction, expressed surprise at the varying assessments of a shortage, but noted that, “in some cases, it’s really difficult to detect, we have a number of subs that I don’t think are growing as a result of it. We think they’re at capacity, so they’re unable to do more work, when actually they can’t find any more people, and that’s why their business is not growing.”

Demographics

Demographics presents challenges on two levels, participants said: One, to replenish worker ranks ahead of an emerging crisis, and for the long-term, as workers from the Baby Boom generation—the largest segment of the work force for nearly 30 years—phase into retirement.

That dynamic, said Don Greenwell, put contractors in the rare position of being at the cutting edge of a national trend. “As an industry, we tend to lag,” he said, because it’s easy to read the tea leaves from falling consumer spending or a drop in residential construction. “Here, we’re going to be the first industry hardest hit,” he said.

Greg Harrelson noted that issues of perceived worker shortage also encompass current work ethic standards. “It’s not just people, but finding qualified people who will show up at 7 and work every day for a full day’s pay,” he said. “It’s finding people who want to do the work that’s required.” Refilling the thinning ranks of skilled craftspeople, he said, “is a huge problem that needs to be addressed.”

Joe Mabin noted as well that the skill sets that are lacking include communication and writing. He blamed some of that on an excessive embrace of technology: “The Millennials I work with have real failings in those two areas,” he said.

As if trying to decide whether to laugh or cry, Courtney Kounkel chimed in: “They forgot how to pick up the phone,” she said. “We have found that people that are 10 feet away are texting each other.”

Chris Vaeth cited that kind of episode as part of the generational challenge facing the sector. “People don’t graduate from school and want to work 60-hour weeks for a paycheck,” he said. With emerging new workers, pay is no longer the primary concern. “I hear it time and again: It’s the intangible benefits, not just a dollar value, it’s a voice in the process, a sense of having an impact, the feeling that I went home having contributed something that day.”

That’s especially true, he says, when young workers see friends hitting a jackpot by creating a successful mobile app. “They want to feel like they’re doing something more than going home with a check,” Scott Kelly, president of Kelly Construction Group, said part of the looming challenge is grounded in the sector’s image with younger workers. “There’s a perception that we’re in an industry that’s very difficult, and that means working only when its 95 outside or 10 below zero, and not a continuous 12-month period. We’re competing against technology.”

Mary McNamara noted that reaching into the ranks of middle and high schools can be one way to plant the seeds of interest in trades careers. The Independence School District, she noted, had taken a Ford Foundation grant to redesign its high schools into career academies, sparking interest from students in science and health care, but also in construction.

And back that up with curriculum changes that can allow the construction interests to finish high school with an associate’s degree in hand, ready to enter the work force. Still, she said, “It’s going to take a much more active role by all construction companies to start to recruit kids back into the business.”

Sheila Ohrenberg said too many school counselors continue to steer students into college tracks, even if the fit isn’t right. “Some are not capable of a four-year education for a variety of reasons, and they don’t realize these are good jobs in the construction industry, where they can take care of themselves and start a family and pay their bills without going to college.”

And they start working, Joe Mabin added, without student debt accrued by for-profit trade schools that don’t provide sufficient value on the instruction for the tuition charged.

It’s part of a larger cultural shift in the U.S., said Bill Prelogar. “When I was growing up, carpenters, electricians and brick masons were the parents of the children I went to school with, and they were well-regarded in the community—upstanding citizens, making good living, supporting families.”

Alise Martiny cited the ability of trades professions to address inner-city work force and poverty issues. “There are unbelievable opportunities for some school districts” to capitalize on that, she said, but an image makeover for contractors would help. “Nobody wants a job that’s dirty,” she said. “Let’s talk about a job where there’s technical skills and opportunities for career advancements. We have to do a better job of marketing ourselves. Yeah, you have to get up early; we don’t start at 9, and your nails will not be gorgeous,” she said, holding up her own. “But these are $33-an-hour hands. We’ve got to turn that around.”

Changes in the Sector

With work returning across the board—and fewer public-sector projects emerging—more contractors have withdrawn from highly competitive bidding to focus on negotiated work.

Everything was bid work in 2010, Courtney Kounkel said, because that’s where the market was. “There was almost no negotiated work.” At a public school district bid request, 17 general contractors were scrapping for the work, “And those are the ones where I think, ‘Oh my gosh, if I’m the low bidder on this, I’m going out of business,” she said. “To be low, somebody had to have screwed up.” Four months ago, the same district issued a request that produced exactly one bidder, she said. “That tells you that negotiated work is back.”

Mark Heit said the market has rebounded from an over-excessive focus on cost that emerged during the downturn. “Back in ’06-’07, clients were forced to develop relationships and performance was important,” he said. “The whole downturn skewed everything to the other side, where it was a cost-driven marketplace because they could take advantage of it.”

Shawn Burnum said he hopes the days of hyper-competitive bidding have passed. “I didn’t like it, but I understood what they were trying to do was create a competitive advantage,” he said of cut-throat bidding tactics being used. “I hope we’ve turned a corner where it’s not all price driven and you have to be the low guy all the time.”

Mark Heit noted that McCarthy just two days earlier had bid on a project worth more than $10 million—and had no competition for that part of the project. But Mary McNamara pointed out that when bids are being taken these days, her 90-year-old company is often going up against new companies that no one has heard of, so there are concerns about the quality of work.

Finance and Regulation

Alise Martiny raised the issue of how changing project-finance and regulation was affecting contractors. The general response: Not very favorably.

“Private development isn’t getting any kind of conventional financing—it’s unconventional conventional bank lending,” said Susan McGreevy. “The banks are under so much scrutiny and they’re so nervous—the backup they require, the title companies require, the escrow companies require, it’s so voluminous.”

Worse, lenders are refusing to allow contractors to modify work on-site without prior approval from the bank, even for small issues—no changes, period. “I tell them, ‘Then give me the name of the guy you’re going to have on site all day, because you’re saying we can’t even move a door knob without bank consent,’ but they say, ‘no we need 10 days to approve anything you’re going to do.”

That’s driving up the cost of projects and delaying delivery, she said.

“Another impact is a huge risk transfer, and that risk is being transferred to the general contractor,” said Dirk Schafer. “Things like date-certain delivery, things like no limitation on liability. In the past we used to shudder when we had liquidated damages. Now we push for liquidated damages, because at least we know what’s involved.”

Another significant trend, said Chris Vaeth, is a decline in public funding at the state level. “Missouri and Kansas contracting had grown fat over the last 20 years on bond money,” he said. There’s also an increase in so-called P3—public-private partnerships—because public entities alone don’t have funds or bonding authority to carry projects on their own.

Wells Haren said incentives like tax-increment financing, had allowed Haren-Laughlin to work on multiple projects, but “Candidly, those would not have been done had that not been there. There’s been talk about reducing that funding, but I hope it doesn’t go away.”

Dirk Schafer noted the impact that Missouri tax-credit programs had made on construction activity. But he said that if any shortage concerned him, it would be in the number of public projects on the horizon.

A final concern, he said, was that the lack of minority and women-owned subcontractors could put a crimp in existing public projects that require portions of that work to go to those companies.

Succession Challenges

Another serious issue confronting the sector, said Don Greenwell, is succession planning—or the lack thereof, especially considering that 75 percent of the Builders’ Association members have fewer than 50 employees. Mom-and-Pop shops are everywhere.

“It comes up in discussion about bonding a lot,” said Teresa Martin. “Succession planning is always a big topic for surety companies, but it’s becoming a bigger one because of concerns about stress in the market and how people are going to manage their business.

One increasingly popular tool, she said, is the ESOP structure, leading to employee ownership for owners who

want to cash out of a lifetime’s investment in a company. “We’ve also seen more key groups of leaders being identified to find ways to help transition through a buy out of older owners,” Martin said. Still, she said, leadership development isn’t where it needs to be in the construction sector.

“In this market, we have an awful lot of family businesses,” said Susan McGreevy, and those companies are successful because they’re good at what they do.

“But this kind of corporate legal planning is not something they are comfortable with, so they just don’t do it. It’s like if I don’t make a will, I’ll never die.”

Sheila Ohrenberg said family-owned companies will be hard-pressed by generational differences. “The 25-year-olds, not as many now are going into the business as would have been 15 to 20 years ago,” she said.

Some of the issue there is a matter of expectations, said Tony Privitera. “Anything in life that’s worth working for, you have to put in the time,” he said, and young workers who want to be thrust into leadership roles are setting themselves up for failure. “Our kids that are in their teens to early 20s right now, they will never see our business the way we saw it,” he said. “Remember the fax machine? It was the greatest thing in the world, faxing bids!” Today, fewer are learning every facet of the business first, he said.

Tim Mooremeier noted that ESOPs, while effective in some cases, could only be used with companies that have shown consistent profitability—something that has escaped many in recent years. “You can’t transition stock to someone in the business if they can’t afford to buy it,” he said.

Issues like those involving the business side are exactly what Blue Hills is attempting to address with subcontractors and other small construction companies, said Adrienne Haynes.

Soon, she said, “we will have classes on how to create a business legacy, how to do succession planning. We’re not teaching them how to do their trade better, but how to run their business more smoothly. … Our challenge is helping people transition from strictly trades to becoming a business person with the back-office skills and not just about project management.”