HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

The odds tilt in favor of patients, businesses

A little more than a year ago, Timothy Pluard made the cross-state career trek from St. Louis to become medical director for Saint Luke’s Cancer Institute in Kansas City. It was an opportunity to get involved in an area of growth that is changing

the nature of cancer care in the Kansas City region.

His charge was to elevate the institute’s profile regionally

and nationally by bringing in more research opportunities and clinical trials. And he took over just a year after the University of Kansas Hospital—just two miles and one state line away—had received designation as a national cancer institute.

That two of the biggest hospitals in the metro area—and the two anchors for health care in the region’s core—are committed to raising their status in both cancer research and clinical care speaks volumes about the way the Kansas City marketplace

is changing in its approach to the nation’s No. 2 killer.

“Do we have the capacity and capability to treat cancer effectively as compared to elsewhere? Absolutely,” Pluard said of the region’s clinical assets. “Has that perception been recognized by people in the community? Perhaps not, but the perception is growing.”

The high-profile efforts at KU and Saint Luke’s are certainly affecting that perception, driven by advances on the clinical and research sides. The pace of change in cancer care, said KU Hospital’s Terance Tsue, has been a crescendo that is still building.

“The major focus of those efforts, especially since we were designated as a national cancer institute, has been in outreach and prevention—trying to detect cancers earlier,” Tsue said. “We’re also trying to educate people to minimize the burden of the disease. That’s one area of focus, and that includes treatments as well as treating the whole patient in terms of other supporting services. We’re not just treating the disease.”

But in cases where cancer has been diagnosed, research is being translated

into new, ever-more-effective treatments,

Tsue said.

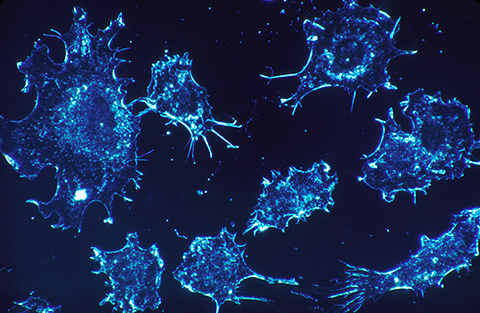

“In terms of the nitty-gritty of cancer therapy, it’s what we call personalized medicine and precision medicine: where you are detecting the genetic thumbprint characteristics for a particular individual’s cancer. Even though they may look the same under the microscope, these cancers are caused by different mechanisms and rely on different mechanisms to go awry.”

Detection of those individual traits is important, Tsue said, because therapies are based on what a tumor looks like under the microscope, and often, “that’s not as effective as killing those tumors as it would be if we knew the original cause of cancer for that particular individual. That’s where genetic analysis makes a difference.”

The Business Factor

Cancer, like any other debilitating illness, is of critical importance to business executives on various levels. For small businesses, of course, a cancer diagnosis for the company’s leader—and a potentially lengthy treatment regimen—can pose a threat to the viability of the organization itself. For larger businesses, executives and managers have the human-capital issues that go along with losing key subordinates, plus the costs of replacing lost hours on top of any disability compensation involved.

So changes in the region’s ability to treat cancers locally can impact businesses here directly and indirectly. But there’s more at work in cancer care than what’s going on at the two big hospitals.

“A broader view of cancer treatment as a whole—and not limited to the Kansas City marketplace—is that there are market forces that have essentially made it extremely difficult for small, independent private oncology practices to economically survive,” Pluard said.

“That has created a consolidation bet-

ween what private practices we had and hospitals and/or health systems, so that most oncologists are now employed by hospitals. That’s just a reality of the market here in Kansas City and across the country, and it’s largely driven by the

cost of drugs and the declining reimbur-

sements for those drugs.”

According to various estimates of the impact on business, cancer:

For those reasons and more, the American Cancer Society has partnered with top executives from leading corporations around the nation with CEOs Against Cancer. The ACS says business is in a unique position to combat cancer—and realize a return on any investment in cancer-fighting programs—because, more than one-third of all cancers are linked to lifestyle factors that could be easily changed—lack of physical activity, poor diets and tobacco use, for example.

And workplaces have links to each of those facets, with cube farms where employees spend hours at a desk and computer, with break rooms that have vending machines disproportionately stocked with low-nutrient/high-calorie snacks

or drinks, and with designated outdoor smoking areas, rather than outright bans on that behavior.

In addition, many companies, even small ones, have implemented carrot-and-stick

approaches to wellness, including screen-

ings that can detect cancer risk or lead to early diagnosis (where chances of successful treatment are better and, generally, cheaper).

Those factors can address causes and costs. But the most sweeping change related to cancer care is what’s happening on the research side, and how that is being translated into effective treatments.

Like Tsue, Pluard sees the same dynamic at work at Saint Luke’s.

“In terms of delivery of care, it is really becoming a highly specialized endeavor, because of the complexities of cancer” that are being identified through genomic studies, he said. “We used to view lung cancer as a fairly singular disease;

we now know that there are molecular drivers that can be identified in individual cases and can be targeted with specific drugs to inhibit those drivers.”

Change Agents

In addition to the NCI designation and KU and changes at Saint Luke’s, the area has seen a number of improvements in its cancer fighting infrastructure:

The Outlook

One other increasingly important factor in the workplace-cancer prevention dynamic lurks over the age horizon: Workers are staying on the job well past the retirement ages that were commonplace in the run-up to the 2007 recession, 2008 banking crisis and 2009 binge layoffs around the nation.

That’s important, because cancer, in large respects, is a disease that absolutely correlates with aging as a function of cell-division processes and lifetime exposure to carcinogens—or both.

Health-care providers have responded to that, as well, by broadening the range of services to address aspects like the psychological and financial impact on patients and their families, through both treatment and rehabilitation.

“That’s a reflection of a shift in cancer becoming a chronic disease,” said Pluard. “So many people are living with their cancer a lot longer than they would have 10 years ago. At the stage of how we facilitate helping these people regain their function and allow them to be productive members of society and lead

productive lives.”

There’s no getting around it, Pluard says: “We know there is a biological clock in every cell, called the telomere, and as it shortens, the cell’s life expectancy diminishes. It can be influenced by external environmental factors, so the

environment may be contributing to it, but there’s a natural aging component, as well.

“We are going to see more cases.”