HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Invariably, the statistic accompanying reviews of how the Baby Boom-generation affected America’s economy, politics and culture notes that, every day, 10,000 Boomers cross the threshold of retiring.

Left unspoken is that, at the same time, 10,000 more are turning 66 … and 67, 68 and 69, through next Jan. 1, when the bar is raised to 70. In other words, we’re on the cusp not just of a retirement boom, but a geriatric boom that will continue through 2031, when the last Boomer hits projected full retirement age of 67.

It’s been said that Boomers could be defined by the social trends, icons and fads they fueled, from Howdy Doody and Hula Hoops to Harleys and Havanas. That stereotype overlooks a fair amount of diversity within this cohort 78 million strong, and forward-looking projections of Boomer impact may do the same. For the emerging reality within that demographic will be harder to paint with a broad brush, from multiple perspectives:

• Financially, for one. Two out of five Boomers have no retirement savings whatsoever, so their later years will be considerably less golden than for the 27 percent who feel confident that their money will outlast them.

• Physically, for another. While the Boomers have engaged in one fitness fad after another, roughly 7 in 10 today are overweight or obese, according to the National Institutes of Health. Again, their futures will be marked by less mobility—and quite likely, fewer years—than for highly active Boomers who are redefining our notions of senior fitness.

• Recreationally, yet another. Already, emerging trends in the travel and tourism sector point to Boomers who want more experiential travel, who want to take their adult children along, and who want to travel with a purpose, fueling what you might call a trend toward philanthropic travel.

It’s almost impossible to identify a business sector that won’t be fraught with change—or opportunity. Take the funeral industry. It may be sobering to consider, but according to the Census Bureau, about 2.6 million Americans die each year. By 2050, that’s projected to surpass 4 million annually, an increase of more than 53 percent. And that stat is all the more sobering when you consider the numbers of funeral home owners are themselves Boomers.

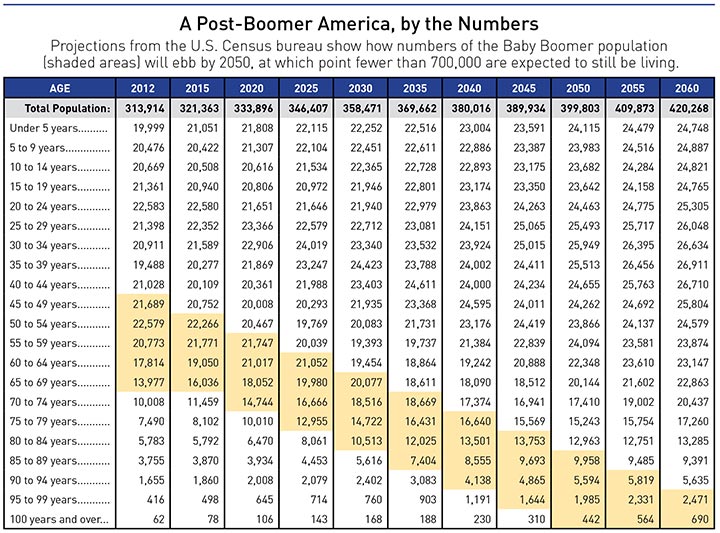

So there’s no denying that the biggest, best-educated and wealthiest generation in history will make a final series of trend-setting pushes between now and 2060, when their projected numbers nationwide dwindle to roughly 700,000. (Advice to mortician-school students; best retired by then, or in another line of work.)

Until we get there, Boomers will continue to influence business and commerce—and the way Generation X and the Millennials, now the largest single age block in the work force, will make a living, and a retirement, for themselves.

For as Boomers exit the work force, they leave behind tens of millions of jobs—many in critical economic sectors like energy, IT and health care, which tend to be higher-paying and which will require educations comparatively more expensive than when Boomers were in school. And they will create demand for millions of new workers at companies with products and services geared toward older Americans, jobs that, in many cases, don’t even exist today.

According to Census figures, by 2050, the numbers of Americans older than 65 will nearly double from the 2010 level, the 80-and-over set will nearly triple in size, and the number of centenarians and people over 90 will quadruple.

In short, there’s plenty of change ahead . . . regardless of your generation.

Lee Norman doesn’t need to go to the roof of the University of Kansas Hospital to get a view of what’s coming. The chief medical officer at the region’s largest medical center can see it in many of the hospital’s nearly 700 beds.

“We take care of those folks now, but it will be a higher proportion” in the coming decade, Norman says. “At its core, it entails two issues. One, economic, because Medicare covers most of the elderly, and the cutbacks in the program are unsustainable if we have higher and higher proportions of Medicare beneficiaries,” he said. That will drive healthcare institutions, in the current format, to financial insol-vency. “We lose hundreds of millions on Medicare patients already,” he says.

Secondly, “the health-care man-power needs will be terrific,” Norman says, because “the intensity of service for the elderly is much greater than for younger patients.” Previous generations were waves on a beach; the Boomers are closer to a Pacific tsunami.

As for patient populations, we can count on at least a temporary reversal of victories in the war on cancer—it’s a disease of aging. So too are neurological maladies, “We’re going to have a huge glut of Alzheimer’s patients,” Norman says. And orthopedic cases, with arthritis and joint failure in knees and hips—and again, not enough hospital beds or qualified physicians to accommodate the demand.

All of that will spawn an increasingly fervid discussion—and perhaps a more honest one—about the costs and availability of end-of-life care. And all of it will have political implications as well as financial ones, Norman says. Whoever is in the White House, Democrat or Republican, will be unpopular when it comes to health care because nobody has the courage to solve it,” he says.

“Staggering.”

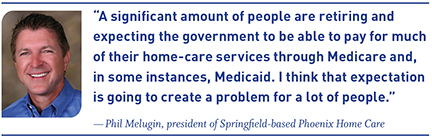

That’s how Phil Melugin, president of Springfield-based Phoenix Home Care, describes looming demand for home-care services, and the Boomers are driving the bus. “The demand for services is going to be extraordinary,” says Melugin, whose company is the biggest home-health provider in the Kansas City region.

But there’s a dark thread in that cloud’s silver lining: “With this generation,” Melugin cautions, “a significant amount of people are retiring and expecting the government to be able to pay for much of their home-care services through Medicare and, in some instances, Medicaid. I think that expectation is going to create a problem for a lot of people.”

Even at this stage of the demographic cycle, the public support already is inadequate. “The current administration has taken many of the funds that used to be directed and reserved for seniors, cutting Medicare significantly,” Melugin said. “I don’t know if that will continue with future administrations, but if it does, it will be difficult to have the resources to care for these millions and millions of individuals who may not have resources to pay for that care themselves.”

Melugin is challenged with finding workers in what is now the fastest-growing job category in the U.S. “While we’re certainly in the home care and caring business, we’re also in the employment business,” he said. “We have to be prepared, from an employee standpoint, to handle the need.” Some of that preparation will require reconsideration of compensation levels, and some will require workers who are able to break difficult news to desperate people.

“From a cost standpoint, there’s little we can do from the client’s end if they don’t have access to public resources and they have not saved privately,” Melugin said. “There’s little we can do but to advise them, provide services they can afford and help them stretch their money as far as possible.”

Either way, he said, “we are a major solution to that burgeoning need.” Nursing-home costs for the public payer, which cover skilled nursing and round-the-clock care, are significantly greater than home care, Melugin noted. “Right now, the cost for keeping somebody in the home through all services, with Meals-on-Wheels, home care and other medical services, is about $ 6,000 a year. For a nursing home, it’s about $42,000.”

As with physicians, the nation already lacks sufficient numbers of nursing-school slots to meet projected demand. He can’t do much about that, and in any case, he’s not in the skilled-nursing business. But he can focus on another dimension of the crisis, since most care workers are trained on the job, rather than through formal education. “We put them through significant training courses here before they ever enter a home,” he said. “I’m not as concerned about the training piece as the supply in the number of caregivers, people willing to do the work at that level.”

Long considered lower-wage jobs, the demand has already affected wages, largely making current discussions about a higher minimum wage irrelevant at Phoenix, he said.

A corresponding piece of the puzzle Melugin is working on is with a burgeoning sector devoted to aging in place—healthspeak for keeping people in their homes, and out of health-care settings, as long as possible.

Keith Blay is living part of that piece now. He’s the owner of Mr. Remodeler, a contractor that has held aging-in-place certification since 2010. “We were a little ahead of the curve at that point,” says Blay, but the positioning is paying off. “There’s definite growth in that area,” which also includes projects linked to the Americans with Disabilities Act. “Between those two markets, it’s been growing quickly, and we’re doing more of that work this year than last.”

Blay’s father, Dean—you may recall the folksy radio commercials from a few years back—was battling health issues of his own before his death in 2013. But, Keith says, “our clientele is older, too, and we could also see it in clients.” With an assist from Steve Kuker, host of KMBZ’s Senior Care Live program, Mr. Remodeler took a new turn.

Yet what was once merely a consider-ation of placement for grab bars and shower-stall seating has morphed into higher design elements, like decorative handrails that complement a home’s décor, and walk-in showers. “In the ’90s, the standard was a corner Jacuzzi with shower neck,” Blay said. “Now, very few use the Jacuzzi, and we’re tearing those out, replacing them with zero-threshold showers made out of tile or onyx. A lot of times, if there’s room, we don’t even have a door to mess with.”

Those are among the biggest client needs, but close behind are changes in lighting—particularly in bathrooms, where older people are more likely to be making nighttime trips around surfaces that are hard, sharp-cornered and wet.

“So we focus on no-skid tiles, and one thing to watch out for in making things accessible is to make sure there is enough room to move, especially with a wheelchair or walker.”

Factor in first-floor master bedrooms and laundry facilities, access ramps, chair lifts, wider doors and even raising electrical outlets from near floor-level to 36 inches (eliminates bending over), and there can be some serious costs involved.

“But the impact is, somebody can put $6,000 to $7,000 a month into a nursing home, and for just a couple of months’ worth of that, we can completely remodel the average bathroom. For a year’s stay at an assisted-living center, you could do most anything to a house to make it more livable,” Blay said.

For most of his 20 years in the medical-device business, Ivan Brown has dealt with making and selling products that help patients recover from injury and surgery—patients of all ages. But demographics are opening new vistas for his company, Brownmed. “The likelihood of either injury or surgery increases as we age because our musculoskeletal challenges increase,” says Brown, whose Boston company has its sales force based in Kansas City. “The injuries may not be sports-related as much as from normal daily activity that happens from just living.”

What’s changing in his sector is that people are living longer because they’re healthier and active. There are plenty of indications that many Boomers—a generation not unfamiliar with matters of self—will want to remain that way, even past age 85 and beyond. “So we have to think: How do our products need to change to adapt to an older customer set?” Brown said.

That includes products that address an individual’s ability to maintain his balance and remain mobile, Brown said. “They do have more pain, and one of the ways they manage is by just sitting—that’s not good. We can help them get healthier, but they won’t be mobile unless we can figure out how to help deal with pain.”

That very challenge presents choices about whether that pain can be managed with medical devices, or requires pharmaceuticals. “Both will do well,” Brown said, “but increasingly, choices we’re making prefer a more conservative approach through a natural healing process. With chronic pain, you can’t just take a pill and the problem goes away.”

And because the healing process takes longer as we get older, there will be demand for more physical therapists, podiatrists and pain-management specialists, he noted.

All of this is fueling an unprecedented level of medical-device innovation. “There’s an exponential increase in the amount of innovation occurring today because of the whole migration of choices in health care from doctor-provided and doctor-directed care to patient-directed,” he said. “It’s really becoming a patient-choice world, where patients are deciding to take charge of their issues and do something about it themselves, rather than let others tell them what’s wrong and determine what needs to be done. That patient choice is really going to influence medical device innovation.”

Cause and effect, in practice: Boomers have long loved their tans. Thus, an explosion in tanning facilities and equipment in recent decades. That’s cause. Effect? Skin cancer demand for cosmetic surgery.

That’s just one way that age cohort has changed just one aspect of health and wellness. But there’s another big one emerging, says Laura Edwards, general manager of 68’s Inside Sports, the fitness centers launched by former Chief Will Shields.

“There’s a fairly large crowd in that age group, me included,” she says. “As far as programming, it definitely has changed the face of the industry. Here’s what’s going to happen: A lot of boutique clubs have been opening, catering to the younger, warrior or iron-type fitness interests, the 20-to-30-year-olds. Then the bigger clubs had to change programming somewhat to add more yoga-type classes, yoga fusion and wellness programming—everything from health coaching to nutrition coaching, and everything basically geared to helping people live a longer life.”

The biggest changes, she said, are with the wellness component of the program. “Health coaching is becoming huge in our industry,” Edwards said. “Taking a look at health history, medications, movements and coaching through process.”

And the equipment involved is changing. “We see a lot more equipment geared for older people,” she said. “When I started, basically there was one piece that older folks could get in and out of quickly. And the duration of a workout is changing, because for the older folks, a 20- to 30-minute workout is what fits.”

At its core, that change compels clubs to view individuals less as clients with isolated fitness needs like weight loss or strength training, and more as clients with broader needs. “That’s been a big change for us,” she said. “We’re doing a lot more wellness programming, starting a weight-management program geared more toward the 40-plus crowd.”

And instead of the old model of pursuing fitness by eating less and exercising more, she said, “we’re trying to help clients balance their metabolism, get their hormones in check so that they can lose weight. And there are more things geared for seniors, senior strength and aquatic programming. All of that is very attractive to Baby Boomers because of the wear and tear of the past”—in her own case, with the high-impact aerobic classes she used to teach.

As a group, Boomers have always thought of themselves as potential world-changers. Having a hand in ending a war can fill one with such confidence, especially if you pull it off in your early 20s. These days, they’re more likely to think of Vietnam as a place where they can take a vacation with their grown children, and perhaps even engage in a service project with work that speaks to a deeper need than merely seeing another part of the world.

Gary Davis sees both trends emerging at Acendas, the region’s largest traditional travel agency, and the Boomers are driving each.

“There’s no doubt that it’s happening,” says the agency’s co-founder. “We have seen a very consistent change in tra-vel habits and tendencies.” Chief among them is that Boomers are less inclined to take the all-inclusive, beach/sun/cocktail trip to sunnier climates. “Now they want to take their families with them—they want an experience, and they want to take their adult children with them.”

Couples travel will remain strong, but families who go to resorts in Mexico, for example, want to know about finding a good zipline to entertain grandchildren, finding a charter boat for a sunset trip or touring the Mayan ruins together. “In Europe, it’s the same thing,” Davis said. “They want to have an experience, they want a guide, they want to learn about the history of the place they’re seeing, and do it with adult children.”

His own belief is that many who can afford to take the whole clan were also those who “worked hard for what they have and did not have a lot of time to travel on own, so their kids didn’t either. Now, they want to pay their kids back.”

Another change emerging is that, even with people who have passed 65 but still haven’t retired, there’s a grow-ing sense that it’s now—or, perhaps, never—to get in more travel. “They’re hitting that age—they’re not all retiring, but taking more time off and enjoying it with their families,” Davis said.

Coming right behind experiential travel, and perhaps an extension of it, he said, “are people who want to travel but want to do something to help the destination. They want to participate: Help build homes, dig water wells, train people to grow their own food.”

In fact, he said, Carnival has dedicated a ship to travel to Cuba—sans casinos or Vegas-type night life, strictly for phil-anthropic purposes.

Remember a decade ago, when business news outlets were projecting market mayhem with the approaching retirements of Baby Boomers? They’d be taking ultra-conservative positions, we were told, or sending the markets down by liquidating portions of their portfolios en masse. Never happened.

As it turns out, even at 10,000 a day, the numbers of Boomers needing to make major readjustments in their investments has been a small part of market movements that are dominated by larger forces and institutional investing.

When it comes to the way investors behaved then and the way they do now—even sandwiched around a monstrous recession, “we’re not noticing much of a difference,” says Lynn Mayabb, managing director for BKD Wealth Advisors’ Kansas City office. “That’s partly because a lot of Boomers did more financial planning than previous generations had done prior to retirement. They had a better handle on their cash-flow needs, on how to invest, and on their own risk tolerance.”

Those factors have added a certain stability to bond and equities markets, as has one other significant factor, Mayabb said: “Many of them have come to realize that their own investment horizons were up to 25 or 30 years, so they didn’t need to be ultra-conservative right away.”

Nor are all Boomers alike when it comes to investing; in fact, two in five have no retirement savings at all, surveys indicate. This generation may indeed have acquired more wealth than any other in history, but that wealth isn’t spread uniformly.

“People who might cash out might be those individuals who didn’t have much invested in the first place,” Mayabb said. “A lot of people in retirement only have a couple hundred thousand, so they might be cashing out simply because they need the cash to live on, plus Social Security and a pension. That’s not going to impact the market very much.”

Given that a man age 65 in 2010 still had a life expectancy of nearly 18 more years, and that a woman had 20, Boomers will be in the market for a long time. The biggest difference, Mayabb said, is that younger generations are framing their plans to discount the role of Social Security.

“There aren’t going to be as many paying into Social Security, and govern-ment is going to have to do something about it,” she said. “Maybe it becomes a true social program, where if you don’t need it, you don’t get, despite having paid in all those years.”