HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Transformative: The Johnson County Gateway project, one of the biggest road and bridge improvements in the region in years, will transform the I-35, I-435 and K-10 connections in central Johnson County, at a cost of $288 million over a three-year period.

In many ways, Kansas City indeed is a metropolitan area on the move. In various parts that’s because:

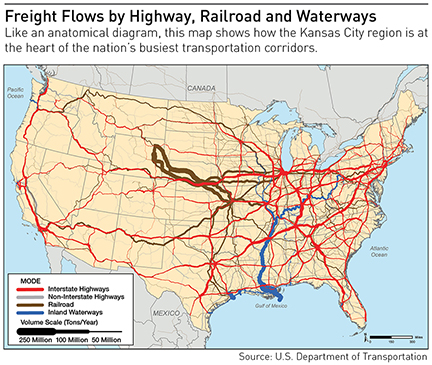

• We have more highway lane miles per-capita than any other city in the nation (and No. 2 Fort Worth isn’t anywhere near us in that metric.)

• We move more tons of freight by rail than any other city in the nation.

• And we’re one of a comparative handful of cities with four interstate highway connections, including the NAFTA superhighway connecting Mexico to the Great Lakes region.

And now, we’ve got a nascent streetcar system, there’s talk of a new single-terminal airport system, and there’s even early movement to adopt light-rail mass transit in eastern Jackson County. It might be trite to suggest that the region is at something of a transportation crossroads. “Inflection point” might be a better way to describe things.

“There are a lot of things that make this a unique time for transportation in general, and for public and mass transit in particular,” says Ron Achelpohl, director of transportation and environment for the Mid-America Regional Council. While proclaiming MARC’s agnosticism on the airport issue, since it’s not involved in the city-run operation, he did note that the agency “acknowledges how important it is to have good transportation connections to the rest of the country and world, and KCI is important for the health of the region.”

And right now, the KCI issue looms as perhaps the biggest transportation matter on the civic agenda in Kansas City. Four proposals, all designed to better comply with current air-traffic security needs, would either rehab the existing Terminals A and B in the three-terminal structure to yielda single master terminal, or scrape Terminal A and build that new single terminal. They range in cost from a low of $964 million to a high of $1.2 billion.

It’s a hot-button issue because of the huge loyalty that residents express for the convenience of the airport, one of the nation’s easiest to get into and out of, but not one where you can do much retail shopping or even mid-level dining. Just last month, the City Council’s aviation committee took time out to consider an unsolicited new proposal that would have kept the terminals in place, made modifications to expand the footprint of Terminal A and create more commercial opportunities and passenger amenities, and slice close to $600 million off the previous low-end proposal.

That one drew instant criticism from those who have been involved in the process, in particular the consultants who say that configuration presented by Crawford Architects simply won’t meet the needs of a key constituent group: The airlines that have to fly in and out.

Jolie Justus, who chairs the aviation committee, feels the pain, but understands that proposals have to come as part of a process that fully engages everyone with a stake in the outcome. It’s not like Chuck from Lenexa can draw up a plan and submit it for consideration when the process is this far down the road.

Although Justus indeed does have a plan in hand from a real-life Chuck in Lenexa.

“We have to get to a place where the City Council, leadership—and the airlines, who have the biggest voice in this, frankly—decide what we’re willing to live with and put to it to a vote of the people,” Justus said. “New ideas and questions aren’t necessarily slowing anything down at this point; what would slow us down is if after all this, the City Council decides it doesn’t like any of the ideas, and we walk away from this for about for 10 years and come back when all the parties are ready to talk.”

So stay tuned on airport developments on that front. Meanwhile, it’s worth noting that KCI makes other key contributions to the regional economy: It moves more air cargo each year than any air center in a six-state region. On top of that, the airport has become a development site for mega-warehouses through the KCI Intermodal Business Centre, a 690-acre project that has completed Phase I, with 1.8 million square feet of what eventually will be 5.4 million square feet of warehousing and distribution space.

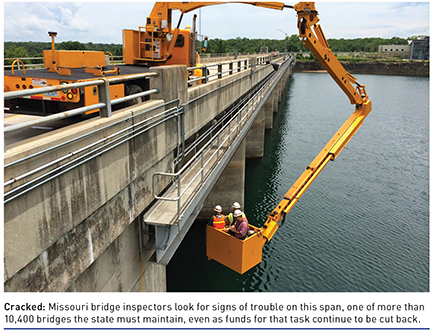

The airport has a big price tag, but even more is at stake for the greater Kansas City region with highway and bridge maintenance in Missouri and Kansas—and that’s a topic where the region has limited control of its own fate. Rather, that’s largely determined by state transportation departments that right now represent a Tale of Two Outcomes.

For nearly a decade, Missouri has seen its highway spending cut dramatically, to the point where the word “critical” pops up in nearly every discussion about spending priorities. Kansas on the other hand, has started to divert money from it transportation outlays to help cover nine-figure gaps in the overall state budget, a process derisively described as withdrawing from “The Bank of KDOT.”

Mike King, transportation secretary in Kansas, says the long-term T-Works road plan the state adopted five years ago can withstand a hit like that—for now. More withdrawals from the bank down the line, he said, would be an issue.

“We were able to do that because we had been overachieving our goals,” King said. “Our internal metrics could afford one year and still be at the level of road conditions wanted.” And those conditions, were he grading them as classroom performance, would rate a solid B. “There are some things we can do, efficiencies and saving, that are not project-related,” he said, and one is bonding—the last bond issue went out at a 2.41 yield rate, which is as close to no-interest borrowing as a state government is likely to find. On top of that, he says, “our operating budget is 20 percent less than when we started with T-works.” That, he said, is what $30 a barrel oil will do for you, especially in a state that relies more on asphalt, rather than the concrete required in more northerly climes.

To the east, officials at the Missouri Department of Transportation are—again—coming to grips with a tight-fisted General Assembly. Since 2011, when the state spent $2.02 billion on construction, maintenance and construction operating costs, the outlays have steadily fallen, hitting $1.48 billion each of the past two years—a decrease of nearly 27 percent.

Perhaps the biggest concern is Interstate 70, connecting Kansas City to St. Louis, but serving as one of the nation’s six key east-west arteries that provide nearly coast-to-coast access. And within that Missouri stretch, “60 percent of our population lives within 30 miles of this corridor, 60 percent of our jobs are there,” says Steve Miller, chairman of the Missouri Highways and Transportation Commission. “Every Missourian, regardless of whether you drive I-70 or live within the vicinity of I-70—your life is impacted by the success of I-70.”

Since there’s not enough to perform the needed work, and the state can’t qualify for additional federal matching highway money, it’s time to think differently, he says. “We`re making Interstate 70 across the midsection of our state available to the nation and to the world as a laboratory to construct the next generation of highways,” Miller says. The state’s interim MoDot director, Roberta Broeker, concurred, calling for greater investment in transportation, including private-side funding. “It’s time,” she said, “to talk about the next big thing. It’s time to energize the state around the possibilities.”

“What we’re doing,” Miller says, “is opening Missouri up to innovators and entrepreneurs to bring to us the next and newest ideas that will drive a new generation of transportation.”

Kansas City has its streetcar. Or is about to. Testing has already begun on the two cars that have arrived, and eventually four will operate along the 2.2 mile route from the River Market to Crown Center. That’s expected to start later this spring, providing 18 stops, roughly two blocks apart, with no fare.

Officials have long argued that the $102 million cost for that starter line was needed to take Downtown development to a new level. But they also concede that, without additions to the first line, the streetcar system will fall short of its true potential to attract more private-side investment. In its current configuration, it won’t do much to change the city’s No. 90 ranking among the Brooking Institution’s list top 100 U.S. cities, ranking by ability to get people to work using transit.

Moreover, voters shouted out a resounding “no” in 2014 when the subject of streetcar expansion was put to them. As with the airport, stay tuned for further developments.

On the area’s streets, mass transit has seen a couple of notable changes, particularly with the effective merger between the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority and the Johnson County-based system, The Jo, early last year. Officials said the move would reduce duplicate functions, streamline services and lay the groundwork for a more truly regional bus system.

Earlier this month, Ford Motor Co. and the ATA announced a collaboration with the urban transit company to launch Ride KC: Bridj. It’s a pilot program that will rely on a network of Ford Transit vans—built at the Ford plant in Claycomo—to provide a new way to access areas of Kansas City that are considered prime targets for jobs and housing.

Robbie Makinen, KCATA president and CEO, said the effort would create “a seamless and borderless transportation network for our residents that is easy to use, comfortable and affordable.” The seamlessness, he said, would include the bus system’s linkage with the new streetcar system.