HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

November 2021

Twenty years into the WeKC awards, more high-achieving women have attained leadership roles in business. But not all barriers have been broken.

A well-worn parody among journalists and pundits for decades involves the editorial slant of a large daily newspaper in New York. A presumed headline touting the imminent arrival of a planet-killing asteroid, the joke holds, would read: “World Ending: Women, Minorities Hardest Hit.”

A well-worn parody among journalists and pundits for decades involves the editorial slant of a large daily newspaper in New York. A presumed headline touting the imminent arrival of a planet-killing asteroid, the joke holds, would read: “World Ending: Women, Minorities Hardest Hit.”

It’s no joke, but that turns out to be precisely the case with the arrival of the 2020 pandemic, though for disparate reasons. Minorities were disproportionately hurt, in keeping with deeply ingrained health-outcome inequities, and women were as well, for the impact of COVID-19 on their careers.

According to the Women in the Workplace 2021 study released in September by the business-analytics firm McKinsey, the dynamic for women in leadership during the pandemic has changed, and not for the better. Whereas before, they were primarily dealing with professional development and performance of employees, their leadership roles have been complicated by decision-making that also impacts employee mental and physical health.

And because working mothers tend to shoulder a larger load of managing the affairs of their children, the stress from all of it has compelled many to consider whether the career track they’ve been on is sustainable.

As a result, the gap between burnout among women and men more than doubled in 2020, the study found.

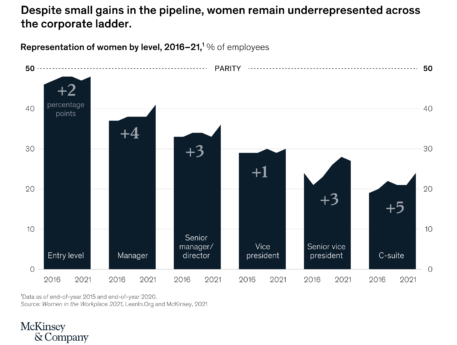

But there’s more dragging down the numbers of women than pandemic stresses. Said the report: “Women continue to face a broken rung at the first step up to manager: for every 100 men promoted to manager, only 86 women are promoted.” And with 14 percent fewer women advancing to those roles, the study said, there is a bottleneck for women seeking to become senior managers, directors, and vice-presidents. And, by extension, C-suite roles.

Against that backdrop, Ingram’s sounded out prominent women in executive roles to reflect on the changing nature of opportunities for women in the workplace, not just during the pandemic era, but throughout their careers. The timing seemed especially appropriate, falling in the 20th year since the magazine introduced its Women Executives-Kansas City recognition program to spotlight executive achievement among women.

When those first awards were made, the thinking was that the need for such recognition might be short-lived. Surely, with the passing of a full generation, the imbalance in advancement to leadership roles in the business would sort itself out—wouldn’t it?

As it turns out, no.

The statistics will bear out a measurable level of progress, as the accompanying chart demonstrates over the past five years. But the gaps between where women are in leadership role and where men are remain stubbornly in place.

Why? “One of the biggest factors to female advancement is structural, specifically those around work-life demands and access to child-care resources,” says Tammy Peterman, Kansas City market president for The University of Kansas Health System. “While things have gotten better, many of the child-care responsibilities in the home fall on the mother. The need for moms to balance these demands is often perceived as lack of investment in their current role, or a lack of reliability when crunch-time arrives.”

Especially in the age of COVID, Peterman said, “finding reliable day care has also served as an obstacle which is impacting the ability of women to maintain the balance needed to advance in leadership roles.”

Her peer at Saint Luke’s Health System, President/CEO Melinda Estes, places more of the onus on employers.

“I think a huge factor in a woman’s ability to advance in her career, no matter how hard she works, lies in her employer’s willingness to invest in her—not just with dollars with but a flexibility that shows a deep understanding about women’s needs in the workplace,” Estes said. “With a culture of flexibility, employers show they understand that women often take the principal role in raising children, and that comes with certain

necessary adjustments.”

Such a culture, she said, recognizes that most career paths don’t progress in a straight line, and that’s especially true for women who often step out of the work force altogether with arrival of a child. But there’s a fix, Estes says, at least within her sector: “By embracing a healthy culture of balance through flexibility over rigidity, health-care leaders can boldly empower women to pursue their individual successes and ultimately create a better patient experience.”

Jeanette Prenger, who turned an IT staffing startup into a $40 million company, sees all the familiar barriers to women still standing tall.

“Unfortunately, prejudice, discrimination, and unconscious bias are still in place,” she said. “Staying focused on doing the right things and allowing ourselves to come back to a point of reference in which we make sure everyone is given equal opportunity will help break down these barriers.”

Not many women have broken thro-ugh as stubborn a barrier to leadership as has Kathy Nelson, president and CEO of the Kansas City Sports Commission & Foundation, which engages with sports-related organizations at all levels, pro, amateur and collegiate. It remains a male-dominated sector, but Nelson thinks there’s an additional challenge built in for women, and it’s not about gender: It’s about age.

“Even my Mom still struggles at times to understand that I’m a female leading an organization in a male-dominated industry,” Nelson said. “And she worked professionally outside the home, and had big jobs. But sometimes I’ll see older men and be greeted with ‘Hey, girl!’ and they don’t think twice about it—there’s no ill respect intended, and they don’t say it to make me feel less. I never hear that from someone my age or younger.”

At the region’s biggest employer, Monica Massey has knocked down a couple of doors—she’s chief of staff and chief innovation officer, as well as executive vice president. She has a no-holds-barred look at the issues here.

“You know what else is holding wo-men back? Women,” Massey declares. “Are we raising our hands? Signing up for the stretch opportunity? Taking credit, taking the podium, taking the lead when the opportunity is presented? Throughout my career I’ve seen this scenario play out over and over again. We gather for a group meeting in a room that has chairs around a big table and chairs around the periphery of the room. Men and women enter the room. Men head to the table and the women entering take a seat along the wall.

“You know what else is holding wo-men back? Women,” Massey declares. “Are we raising our hands? Signing up for the stretch opportunity? Taking credit, taking the podium, taking the lead when the opportunity is presented? Throughout my career I’ve seen this scenario play out over and over again. We gather for a group meeting in a room that has chairs around a big table and chairs around the periphery of the room. Men and women enter the room. Men head to the table and the women entering take a seat along the wall.

“You know where I head? Yes—I head to the table, and not once has a man not made room for me there.”

Her success there is confirmation that intentionality works. She was the only women to join the leadership club when she arrived in 2006, brought on by new CEO Rick Smith, who “was deliberate in bringing me on,” Massey says. “I was part of his plan to increase diversity—in gender, age, experience. He was determined to change the face of the organization that, at the time, was made up of white men over 40.”

Since then, DFA’s hiring and promotion of women to leadership positions has continued that intentional focus, and the firm has added an Executive Leadership Development Program to ensure that women are represented, she says. “We do the same with our internship, mentorship and scholarship programs. … We are keenly aware women are over mentored and under sponsored. As such, I am focused on the sponsorship of women in my industry and organization.”

Each of these executives addressed the transformative power of mentoring, and what it meant to their advancement.

“I am very fortunate that over the years I have been mentored by some amazing women leaders as well as men who saw my potential, and offered me opportunities,” said Prenger. “I’ve used that same type of development with other leaders, from within and outside of my organization. From high school girls looking for guidance, to those already in their careers wanting to explore how to advance themselves. I have scholarship opportunities for younger women and I enjoy providing exposure and networks to those already in their career.”

Peterman, as well, has seen the power of mentoring—on multiple levels.

“I have had the opportunity to spend time with aspiring leaders in many areas of our organization,” she says. “In just the past couple of weeks, I’ve met with a medical resident, a health-professions staff member, and of course I regularly spend time with nurses looking for professional advice. On a personal note, I am the mother of two daughters who have successful professional careers. Part of the role of a parent is to be a mentor and a role model. I have demonstrated the ability to be a successful professional as well as an engaged parent.”

Uncountable numbers of companies have demonstrated effective strategies to effect necessary change. And, as the mentoring experiences show, high-ranking executives can boost those efforts by making it a personal mission. But the impetus for change must include proactive measure by those who aspire to advancement, execs say.

“I believe strongly that every opportunity open to you is an opportunity to learn, whether it’s being placed on the smallest committee in the organization or chairing a multi-faceted, cross-functional strategic task force,” Estes says. “As you grow in your career, it’s essential to do the work—even the things you’d rather not do because they’re not fun or glamorous or easy. Punching your ticket—doing those essential things—teaches you the lessons you need in that job and gets you ready for the next one.”

Too often, she says, women may wait for the “perfect” opportunity. “But the fact is, a career is simply a series of opportunities and roles that—when done well with integrity, skill, and kindness—will lead to more responsibility, more opportunities, and more success.”

Massey concludes with a story about her college-graduate daughter’s hiring experience, a tale that offers a lesson for the way even women devoted to the cause frame their responses.

“When she asked me with help on how to respond to an offer she thought was too low,” Massey says, “I told to craft a message saying ‘I’d like you to consider…’ She quickly shot back to me, ‘Why do I have to ask them to consider? I want X. It’s what I’m worth.’ Clearly, I raised her right. Clearly, I have a ways to go myself.”