HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Shaping a new generation From Classroom to C-Suite

PUBLISHED FEBRUARY 2024

What does it take to be recognized as an Icon of Education? It starts with an intense passion to teach. It requires a steadfast commitment to improving the lives of students. And it implies exceptional achievement regardless of job description. From the chancellor’s office to the high-school classroom, Icons can be found anywhere in the K-20 spectrum. The leaders of tomorrow are not products of wishful thinking; they are students today who are being taught by individuals like these. Meet our 2024 Icons of Education.

Mauli Agrawal, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Mauli Agrawal, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Call it the higher-ed corollary to the Butterfly Effect. In this case, a youngster growing up in India sets his sights on a mechanical engineering degree, and 50 years later, an urban university in the middle of America undergoes a transformation. Mauli Agrawal promised just that when he was named chancellor of UMKC in 2018, and he has delivered with critical program expansion, with large-scale physical improvements, with greater focus on attracting students and with deeper connections to the business community. “India was a third-world country at that time,” he says. “Your opportunities were limited if you wanted to make a living—it was either doctor, lawyer or engineer.” Fascinated by the U.S. space program in the late 1960s, he gravitated toward engineering, earned his degree and came here for advanced studies at Clemson and Duke universities, leveraging available scholarships to earn his Ph.D. and joining Duke’s faculty to work in plastics, polymers and other materials with bioengineering potential. “That field was just beginning to open up, especially in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, how to grow tissue,” he says. Administration wasn’t in the cards—yet. “I was very happy doing a whole lot of research, inventions, patents, but I got a tap on the shoulder, from someone who said they had an administrative position. That started it.” Mind you, Agrawal was tapped on the shoulder often but didn’t budge. Then, the chance to put his own stamp on an emerging program was too compelling. Over the next 15 years at University at Texas-San Antonio, he helped elevate an institution from barely more than a community college to research university status. Then came another shoulder tap. “UMKC was on a much higher level than UTSA was when I started there,” Agrawal says. Guy Bailey, a longtime mentor in Texas who would later become UMKC’s chancellor, made the sale. “He said, ‘when I’ve told you about other jobs, you ignored me, but don’t ignore me on this one.’” He didn’t know much about Kansas City, but quickly learned it was moving in the right direction, Downtown was growing, and he saw plenty of untapped potential on campus. “I said I’ve done it in San Antonio, I can do it again here.” An early priority was the school of engineering—now the School of Engineering and Computing—and one of his first stated goals was to double its enrollment. His 10-year goal to double its research funding was met in five, and he’s overseen plans for a major facility upgrade for the School of Medicine on Hospital Hill. And this past fall, he says, “we had the largest incoming class in history of UMKC” as it continues to attract under-served groups of prospective students.

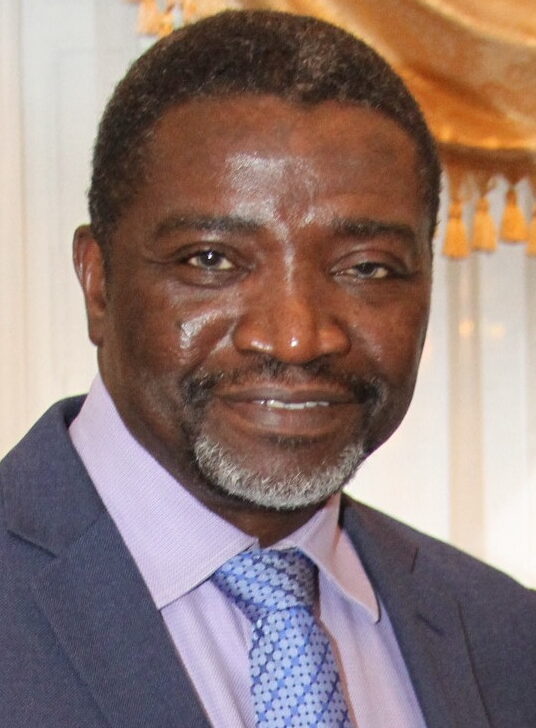

Elimane Mbengue, Académie Lafayette

Elimane Mbengue, Académie Lafayette

Once he’d set his pathway as an educator, it was easy to tell where Elimane Mbengue was headed: “It is my belief that whenever you are passionate about something you should give it your best and go all the way to the top.” That he has done as head of school for Académie Lafayette, the independent charter school that serves more than 1,300 students on three campuses from Midtown to Brookside. The first steps on his journey, he says, came in his native Senegal. “I have always dreamed of becoming a teacher; in my home town, almost every house has a teacher,” he says. Being a teacher was considered a prestigious profession, he says, and the best students passed selective admissions exams, with lodging, food and uniforms paid for by the government at that time, and they had more lucrative careers. His first move after high school was toward law school, but education called to him. “My friends were surprised because I was a brilliant law student and they thought that I could become a lawyer or a judge,” he says. “My dream was to become an elementary school teacher.” After starting in school-district administration there, he came to America and started as a French teacher in Portland, continuing his studies in business management and executive development before taking his role at the Kansas City school in 2012. “School administration is a natural fit for me because I have always been a community leader at different levels serving people,” he says. “I have always been involved in serving as a volunteer in a leadership capacity since a very young age as a neighborhood youth association leader, a student organization leader in Senegal, the president of the Afro Caribbean Society at the University of Exeter in England, the founding Coordinator of the Senegalese association in Oregon.” Académie Lafayette, he says, provides a great immersion education that gives students advantages over their peers. “They have more cognitive flexibility and better social emotional development,” he says. “Our students have always been well-appreciated by high performing high schools. They have always been the valedictorians at Lincoln College Preparatory Academy. Over the last decade, we have built a solid collaborative culture focused on student safety and academic achievement.” Can that success be replicated elsewhere? Indeed, Mbengue says: “To replicate such a model, it is important to have the following pillars: A strong caring and supportive school community, high expectations for every student with a very rigorous curriculum, a culture of professional collaboration, adequate support for struggling students, a stability in effective leadership, and accountability for all.”

Andrew Martin, Washington University

Andrew Martin, Washington University

Andrew Martin, the professor, aspired to be Andrew Martin, the dean. He came to that conclusion after taking a year-long mid-career sabbatical from Washington University, where he’d been vice dean of the law school, to reflect and recalibrate. Then came the opportunity to oversee the college of literature, science and the arts at the University of Michigan, and his dream was realized. How’d that move go? “It was awful,” he says. No, not the work—the impact on his family. “The only reason we went was my job.” His daughter at the time was only six, just starting school, he could walk to his St. Louis office, there were lifelong friends and family being left behind. “We didn’t want to leave, but we decided as a family to put career first,” he says. “It was a very mixed emotion for us.” And yet his daughter was confident that the story wasn’t over. When he brought home the news that he’d been invited to become WashU’s chancellor, “she told us ‘I always knew we’d be coming back to St. Louis.’” And so it was. Since succeeding Mark Wrighton as chancellor in 2019, Martin has orchestrated multiple strategic moves to strengthen and diversify the university’s enrollment, improve its already lofty status within academia, and bolster ties with the business and civic community. He had long before established his credentials in the academic nexus between math and political science, as an instructor, research and author, as well as administrator. He can trace that path back to his high school in Indiana, which not only had a strong honors program, but one that included applied math research. “I was a nerd,” he confesses, but “I was fortunate to be surrounded by talented teachers, and both of my parents had been educators.” After leaving William & Mary as a political science-math major, he pondered graduate school. WashU was the perfect setting, then it was on to Stony Brook in New York for two years before he returned to Saint Louis. “I just wanted tenure, to write, teach, think and do all those things,” he says. Leadership opportunities tend to find their way to talent, and that door opened for him at WashU: directing a graduate-level program, serving as vice chair, then department chair. The work was rewarding, but should that be the next step? That’s where his extended leave came in. “I spent a year writing, thinking, and decided I wanted to come back. I wanted to be dean of and arts and sciences college.” As chancellor, he’s led initiatives like Gateway to Success, which began with a $1 billion commitment to underwrite a no-loan program that helps students finish school without going into debt. Another is Here and Next, a strategic plan that engages hundreds of people in the community to help shape academic direction. “We touch St. Louis in so many ways, but haven’t always done a good job telling that story,” he says. With a renewed focus on doing just that, he says, “really impactful, good things are coming.”

Elaine Mauldin, University of Missouri

Elaine Mauldin, University of Missouri

Elaine Mauldin entered the world of public accounting in an era where you’d find a lot more jackets and ties in the office than skirts and heels—and when barriers to leadership positions were considerably stouter than they are today. She worked in that world for 17 years, including time at an accounting firm and as CFO for a construction company, before making a bold mid-career move: Going back to school to earn her doctorate. Securing those academic credentials, though, was only half of the story of how a fifth-generation Nebraskan became a Show-Me state transplant. One of the reasons she joined the accounting faculty at the University of Missouri in Columbia had more to do with what happens out of the office than what happens in it—she and her two girls had visited friends at the Lake of the Ozarks, and soon fell in love with it. After all, 54,000 surface acres of wide-open reservoir will have a certain cachet for anyone who has to drive three hours to a watering hole one-tenth that size, as most Nebraskans must. Those friends, as she noted in a Trulaske College of Business profile, would urge her to “just get a job” in nearby Columbia. With a little persistence, Mauldin was able to come on board at Mizzou as an assistant professor in 1997, and she’s still a fixture there, conducting research, publishing highly technical papers on things like uses of data and analytics in accountancy and teaching grad-level courses in information systems and auditing. “I still like research to this day,” she said. “It’s a perfect job for me. If you get bored in academia, it’s your own fault because you get to pick your research projects and you get to pick co-authors. … And then you get into the service stuff and that’s very appealing to me.” On that end, she’s earned recognition from Springfield-based FORVIS as its distinguished professor of accounting at Mizzou, and she’s past president of the American Accounting Association, which recently bestowed on her its Outstanding Service Award, recognizing service that goes above and beyond the call. On her research palette are subjects like internal controls, corporate governance, and assurance, and her authorship history includes pieces in a host of niche publications, such as Accounting Review, Contemporary Accounting Research, Journal of Accounting and Economics, and Journal of Information Systems. Not your typical night-stand reading section for most folks, but “I was always interested in academics,” she said in her Trulaske recognition. “I love them. I loved going to college, I love getting degrees. I’m kind of a nerd that way.”

Shari Bax, University of Central Missouri

Shari Bax, University of Central Missouri

Shari Bax doesn’t even pretend to hide it: “I was definitely not the same as the other kids in high school,” she says. “I was a total geek. My teenage children would totally confirm that.” That trait manifested itself with a precocious interest in public policy, one that drew her to become politically engaged even at that stage of life. “I got involved in a push to revise the Alabama constitution when I was in high school, and was fairly young when I worked on campaigns. But I’ve always been very interested in the constitution and the law.” That interest became a career-defining track for Bax, who today is vice president of student experience and engagement, as well as a professor of political science, at the University of Central Missouri. She’s been there ever since wrapping up her doctorate at the University of Tennessee in 1997. Initially, her career goal was to work in the political realm, not on campus. “I went to grad school thinking I’d work for a government agency or a think tank, crafting policy,” she says. But as a grad assistant, “they put me in a classroom, and I loved it.” So much so that academic administration never made it onto her radar until a former campus executive asked her to consider a student-engagement role, which has blossomed into her current one, where she brings a blend of advisory, mentoring and support skills to help students navigate college life and further their own civic engagement. “I still teach, even now, but the most I can teach is one class a semester,” she says, whether that’s familiarizing freshmen students with foundation of government or seniors about municipal administration. “The faculty position that brought me here was a perfect fit for me,” she says. “It was broad enough to allow me to teach in fields where I had interests, like applied learning—internships, opportunities to do simulations in class.” The plan was for three or four years in Warrensburg before the next major move. But, she says, “I fell in love with this place. I fell in love the mix of students, with the faculty, and with the entire university commitment to helping students realize their potential and become the amazing working professionals they are.” It’s a bit more challenging to operate in a political environment like the current one in the U.S. when, as Bax notes, “there’s a lot of cynicism right now.” But much of that is directed at national politics, “so I urge students to stay engaged in state and local politics. One thing I’ve always tried to do is help them connect with more state and local politicians to see the positive work that can be done. You can hear all the negatives every day, but when you develop a relationship and get to know the person doing the work, you also start to see why they’re doing it, how they see the world and how it’s causing them to make choices.”

Tim Nendick, Rockhurst High School

Tim Nendick, Rockhurst High School

Long before he was building a championship-level robotics team at Rockhurst High School—before he was a student there, in fact—it was easy to see that Tim Nendick was wired … differently. After all, how many kids do you know have actually fabricated a trebuchet in their back yard? Succeeding as a student required hard work and sacrifice from his parents, he says. “Both of my parents helped me learn to ask questions of myself and the world, helped me learn to overcome challenges and provide a place of safety and welcome as I grew up.” After carrying his Jesuit education to a higher level at Creighton University, Nendick boldly headed out, teaching halfway around the world at a Jesuit school in Kigali, Rwanda. “It is neat,” he says, “to see some of the same pedagogy and ideas half a world away, in a place often at right angles to Kansas City.” He would return to Rockhurst to pay forward some of what he’d received in his youth. Some of that comes with the robotics team, which in 2022 won the Missouri regionals and advanced to the world championships. Entering that competitive realm came as a revelation: “The scale of the program took me years to really understand,” he says. “Thousands of teams, 50 countries … seeing literally 100,000 students all trying to solve the same problem—it’s an experience that is so incredibly hope-filled.” He pays tribute to a litany of instructors who challenged him and made learning fun, traits he hopes to emulate with his young charges. There is value, he says, in the tangible, the authentic, the challenging. “There’s nothing here that’s ‘given’—the solutions to the problems don’t exist until the students solve them,” he says. “The parts that need to be built need to be thought of, then sketched, then designed—long before there’s aluminum chips and noise and all that—there’s students being faced with a novel problem and being invited to answer a really fundamental question ‘how do you fix it?’ Students need to prototype and build and—most important—fail in order to field a robot that is competitive. Much of our time is spent saying yes to an idea and finding a way to make it work.” Learning how to fix and program and interact with technology as it changes is fundamental, he says, and it’s a skill that’s not going to disappear. “The key thing,” Nendick says, is helping students find what makes them come alive, find what the world needs, and find the intersection of those things and help them live that answer. … It’s critical that we continue to form the whole person, and make sure there are little corners of the school where a young person can throw themselves into community and questions, and experience the world for themselves. Having that open door, and gently encouraging students to walk through it—that’s the key job of the school.”

Jo Weller, Brown Family Foundation-Kansas City

Jo Weller, Brown Family Foundation-Kansas City

Meet Jo Weller, your living, breathing proof that a teacher’s passion need not reside in a classroom to shape young minds and lives. A theoretical mathematician, she taught at UMKC, Rockhurst University and St. Teresa’s Academy before bringing that passion to the Brown Family Foundation as director. There, Weller has found a higher calling—but it didn’t come easy. “Leaving the classroom was the hardest professional decision I have ever made,” she says. “As my career advanced, I began engaging with educators from other disciplines and schools. I came to realize that obstacles and excitement for academic success were broader than my world of helping female students in mathematics. I also realized I had so much more to learn as an educator.” In 2020, the foundation gave her an opportunity to solve new kinds of problems, and new things to learn—“a winning combination too good to pass up,” she says, and she considers herself fortunate to work at that scope and scale. “Engaging with urban, suburban, and rural schools and the entire pre-K to post-secondary pipeline provides a unique perspective and allows me to learn alongside outstanding educators every day,” she says. The foundation is a non-profit formed by Rockhurst High alumnus Mike Brown and his wife, Millie, to further education initiatives in the region. He’s the founder of Euronet Worldwide, the global cash-payments platform; she is a nurse by training who also holds an MBA, and together they have donated millions to education. After 20 years at St. Teresa’s, Weller signed on with the Browns. She grew up in rural Missouri—her high school graduating class had just 13 students—and was the first in her family to finish college. But her teachers were inspirational. “As the only student taking physics or advanced math my senior year, the school could have easily decided not to allocate resources to support two classes for only one student—let alone a female in STEM classes,” she says. “That could have been the end of my passion and pathway for a life in education.” Instead, she designs strategies to overcome systemic barriers and give more students access to meaningful instruction. “A priority for our work at BFFKC is recruiting and retaining high-quality teachers,” she says. “This includes access to relevant professional development, multiple career advancement paths, and appropriate compensation. It is an uphill battle that we are not shying away from.” BFFKC has trained more than 1,300 teachers and embedded 37 key leadership and instructional positions in regional schools, she says, “to help meet the increasingly specialized skill sets required to support today’s learners.”

Ben Wolfe, Kansas State University-Olathe

Ben Wolfe, Kansas State University-Olathe

Just a hunch, but we’re betting that Ben Wolfe is the only collegiate chief executive in this region—America, even—whose resume includes studying volcanic rock in the Aleutian Island and coal deposits in Australia. The CEO of Kansas State University’s Olathe campus earned his degree in geology from the University of Nebraska, and a master’s in the field from the University of Alaska. The final piece of his academic trek—a doctorate in educational leadership and policy from KU—connects the dots to his current duties. “I have a passion for geosciences—especially geoscience education and exposing students to the science behind the natural environment all around us,” says Wolfe. “There is so much beauty in landforms and landscapes and to me, understanding how they were shaped and molded adds to the story.” It might surprise you that someone well-versed in geologic time can so fully grasp the urgency of where post-secondary instruction stands today, especially with its ties to work-force development. That’s where KSU-Olathe plays a unique role, and a fitting one for Wolfe, whose work touched on those same concerns at KU’s Edwards Campus in Overland Park, and his board duties with the Johnson County Education Research Triangle. “I thrive on being a part of growth, ideation, building new programs, and thinking differently about how education is delivered,” he says. He was drawn to K-State while still at KU because “I saw K-State Olathe had so much untapped potential.” At KU, he says, “I learned how critical it is for higher education to be actively engaged with industry and not only the need to leverage advisory boards to give input in the development degree programs, but also in developing just in time training, short term certificates, microcredentials, and non-degree related education.” It also allowed him to see how the work-force needs of the metro have evolved, and continue to, as well as to anticipate the emerging new jobs and careers of tomorrow. To that end, his agenda over the next five years includes boosting campus enrollment to 500, increasing the yearly-awarded research revenue, diversifying revenue streams and strengthening the pipeline of industry and community partnerships. There are also program enhancements in advanced manufacturing and supply chain, and a new research focus on food as medicine and community health—all pillars of the regional economy. “We seek to challenge the status quo and disrupt the traditional paradigm of higher education,” Wolfe says. “This means rethinking traditional degrees, or what a degree might even look like.”