HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Many an entrepreneur dreams of the day the business will bring the kind of wealth that can create a philanthropic legacy. John Sherman was no different after his energy-services company went public in 2001. The money was nice, but something was missing.

“We were growing rapidly and began to think more seriously about how to give back to this community,” Sherman says. “It wasn’t very strategic. I was just kind of wandering around with a checkbook in my hand.”

Well, if John Sherman brought anything to the leadership roles of multiple companies, it was an appreciation for all things strategic. He’s no longer wandering the landscape looking and trying to figure out how to make a difference.

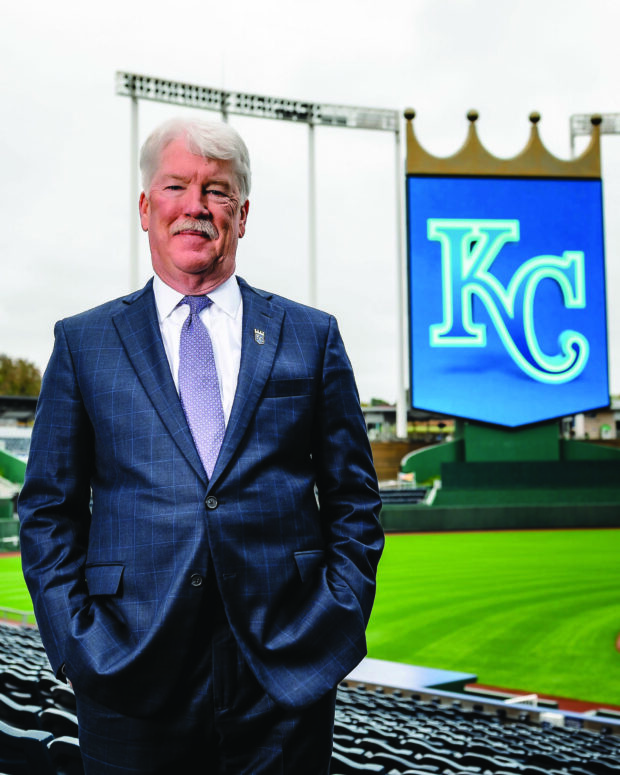

Across innumerable philanthropic causes, through personal and corporate foundation contributions, through his commitment to pulling up the economic ladder as many as he can carry, Sherman has literally changed the face of giving in the Kansas City region. For that, he is Ingram’s 2020 Philanthropist of the Year. It is recognition he says wouldn’t have been possible without his co-pilot in life, Marny, who influenced and executed many of their shared donations of time, talent and, yes, pages from that checkbook.

“Marny and I were both raised in loving families that emphasized a deep sense of responsibility,” Sherman says. “We also have a deep belief in the idea that where you end up should not be dictated by where you start. So, if you look at our philanthropy, it’s all centered around underserved segments of our society, around families with high economic need. What a shame it would be if we left a group behind just because of their ZIP code or the circumstances into which they are born.”

His view on education is a pillar of that philanthropy. “In my view, education is the great equalizer,” Sherman says. “It levels the playing field. Everyone deserves the opportunity to develop their potential.”

When people overcome their circumstances and reach their potential, he says, everyone benefits. “We’re realists, of course. We know we can’t change the world, but if we can help Kansas City become a place where more people have the opportunity to reach their potential—even if one person at a time—change will continue to happen in important ways.”

Social justice and equity, Sherman says, are critical components of this. So his giving takes place through a lens of work-force development, business formation, job creation, tackling crime and a broader sharing of economic prosperity.

“I’ll say it again, but in a slightly different way: when more people have the dignity of work and achievement and access to opportunity, we all benefit,” he says.

The transformation into strategic philanthropy, he says, “is driven by a mission to offer more opportunity to underserved members of our community. Our focus is on positively impacting the lives of Kansas City kids. We believe it’s where the greatest impact starts. That leads us to not only support education, but to specifically support institutions where economically challenged kids can have equal access to educational opportunity. These young people have untapped talent. They have big dreams. We want to give them educational opportunities to leverage both.”

That can take the form of scholarships. Or funding for teachers and their professional development. Sometimes, it simply means a safe place to study after school or a part-time job or work study to build skills and confidence. It all goes back to the mission, he says, adding: “We should be recruiting teachers like we do athletes.”

As for the specifics of crafting a giving strategy, he says it starts by documenting when a grant is awarded, then tracking the progress the agency accomplishes. “We coordinate with the people who do the work, and we agree on outcomes,” Sherman said. “We also work hard to learn alongside them, and understand how to measure those outcomes.”

In it Together: John Sherman credits his wife, Marny, with being the driver behind many of their philanthropic efforts.

When it’s time to review, and potentially continue to partner and invest, the next step is to measure progress on agreed-upon goals. He checks off a quick mental list of organizations that fit those parameters: Operation Breakthrough, Emanuel, St. Mark’s, Front Porch Alliance and the Family Conservancy among them.

“One of the greatest examples of our involvement is Cristo Rey, for which I can take no credit,” Sherman says. “Marny was a founding member of the board of directors. Her involvement led us to have students working in our business as part of a work-study program. As a result, I had a front-row seat to the real transformation that happens when opportunity and education meet potential.”

One day, he says, his wife came home after a meeting and told him he needed to hire more of those students at Inergy, LP, then his primary business focus. “Needless to say, we hired the students,” he says. “Inergy and now our successor, Crestwood, has employed those students ever since. I always believed we got more than we gave through that experience.”

Sherman’s business success has never been a matter of simply climbing a ladder one rung at a time: He built his own ladder on the way up. After working in the liquid-propane gas sector (he was an executive with Ferrellgas for seven years), he demonstrated the essence of the Kansas City entrepreneurial spirit. His first venture was LPG services, which he built into one of the nation’s biggest wholesale propane marketers before selling to Dynegy in 1996. Some of the proceeds from that deal went into the launch of Inergy, an energy company that attained an enterprise value of $5 billion before being sold to Crestwood Partners in 2013.

He stepped out of the energy-sector batter’s box in 2016 and become a minority owner of the Cleveland Indians. Then he turned his attention to absorbing the fundamentals of major-league baseball ownership and operations before pulling the trigger on the Royals deal last fall.

On its face, the Royals acquisition was a straight business deal. Except that it wasn’t. For one, Sherman was taking a baton that had been passed directly from Ewing Kauffman to the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation to David Glass before him: All of it was in step with Kauffman’s gift of the team to the foundation would keep the Royals anchored to Kansas City.

For another, in putting together the new ownership group, Sherman turned to some true superstars of both business and philanthropy in this region. He drew on a career’s worth of power networking to attract well-known area executives like his partner at MLP, Bill Gautreaux, the Lockton and Dunn families, the family foundation of former Kansas City Southern CEO Mick Haverty, UMB’s Mariner Kemper and the Kemper family, and Creative Planning’s Peter Mallouk and his wife Veronica. He also pulled in some he-avy hitters who tend to keep lower profiles: names like Terry Matlack of VantEdge Partners and former Bartlett & Co. CEO Jim Hebenstreit. And later, Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes and retired Black & Veatch CFO Karen Daniel.

As a group, they know Kansas City; they have made fortunes here; they are committed to the region’s success. “We view the team as a community asset,” Sherman said. “We have the privilege and responsibility of being only the third stewards of that asset. I’ve said many times before that it’s really a dream to be able to do this in your hometown.”

Few cities, he says, boast teams with such stability and continuity in ownership. “Ewing Kauffman wanted to sell it at a time when there wasn’t good depth of local buyers. So, he kept it until he could find the right owner,” Sherman says. “David Glass passed it to us with the same intentionality, as Ewing passed it to him. We have a generational group of owners who are wholly committed to keeping the team here for the long term.”

That’s important in a year with multiple social challenges. “This year especially, the leadership from each of Kansas City’s sports franchises was, I think, important and impactful,” Sherman says. “Through our collective support of economic relief, social justice, food insecurity, voter registration and other community needs in a pandemic, I hope we demonstrated our commitment to positive impact. Franchises should do good in the community, and the Royals have a legacy of doing so since its inception. We expect to not only continue that mission, but to take it to another level.”

He has said often that while many things divide us, our sports teams unite us. “This past summer, we worked to deliver a sense of normalcy and enjoyment for our fans during these remarkable and challenging times,” he says. “As we look toward 2021 and beyond, we have even greater hope for the future. When you come out to The K, which we’re looking forward to doing this summer, it doesn’t matter where you work or how you voted or what kind of car you drive. In the stadium, we’re all in it together, rooting for the home team.”

Among the awards that must make the shelves groan in his office, Sherman has been recognized as Ernst & Young’s Entrepreneur of the Year (2002), Entrepreneur of the Year by UMKC’s Bloch School of Business (2009), and recipient of the National MS Society’s Hope Award (2012). He also was part of the first class into the Bloch School’s Business Entrepreneurs Hall of Fame, along with Ewing Kauffman and Lamar Hunt. In 2017, he received the Henry W. Bloch Human Relations Award.

He has a seat on the board of directors for Evergy, the region’s biggest utility, and is a trustee for the Kauffman Foundation and the National World War I Museum. He’s past chair of the Civic Council of Greater Kansas City and the Truman Presidential Library Institute. He is also on the Board of Directors of Teach for America Kansas City.

Marny, he says, has been his major source of support through many of those engagements, and together they founded the Sherman Family Foundation, which provides the bulk of its philanthropic donations to educational causes in the region.

The overall goal of all that is to partner with strong agencies in our region, he says—to learn from them, then allocate resources to help them achieve their objectives and desired outcomes in ways that align with their priorities as donors. “One thing we’ve learned is that you can’t get frustrated by the macro numbers,” Sherman said. “It’s incredible to see the impact on a single person, a single life. Generational transformation for their family happens as well. It’s a 360-degree impact.”

Influenced throughout the early years of his career by Ewing Kauffman, Sherman hopes to now be carrying forward a legacy crafted by Mr. K. and a litany of others he sees as civic pathfinders.

“There is something in the water here,” Sherman says. “Role models with the last names of Hall, Bloch, Stowers, Helzberg, Dunn, Sosland, Sunderland, Berkley, Kemper, Patterson, Illig and many others have all changed the face of our region. Wherever you drive, you’re reminded of what they each did for neighborhoods throughout our city. Their impact is evident, and it lives on. It raises the bar for all of us.”

While he says he can’t speak for all of them, he’s confident that each was rewarded beyond their dreams. But their successes didn’t stop there. “It became bigger than the individual, and they shared their blessings with others,” Sherman says. “They set the expectation through their example and others have followed. I participate in groups all the time where business leaders check their parochial self-interests at the door and focus on the greater good.”

He hopes all of his effort, in a small way, carries on. “It’s part of the culture of Kansas City that we fight above our weight class,” Sherman says. “It has struck me so many times. We’ve been the 29th- or 30th-largest metro area, but we consistently raise and distribute money like we’re in the Top Ten.

“My hope is that there will be a new generation to carry this forward. I’m seeing them in the Royals ownership group, where I’m energized by their passion, their strategic energy. There is a new generation of entrepreneurs that will be our region’s future philanthropists. I am both encouraged and highly confident in their collective potential. As they say at Cristo Rey, we “look forward to the good that has yet to be.”