HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

The pieces are laid out on the economic chessboard for 2016—rising interest rates, slow growth in China and Europe, a widening skills gap within the U.S. work force, indications of a long-overdue market pullback, retirement-induced stresses on federal spending, sharply low energy prices . . . It’s a long list. There are, however, additional pieces that will come into play. When and at what point, we can’t know yet.

But how will those pieces, known and unknown, interact during this coming year? What will their interplay mean for business owners? For investors? For employees and retirees? The short answer—as always—is that we’ll know next Dec. 31.

For those with less patience and a desire for more insight, Ingram’s again turns to expert minds in the fields of economics and financial services, and they give us some guidance on what to watch for in this new year. Spoiler alert: Some of it isn’t pretty. Then again, some of the ugliest economic periods in U.S. history have been replete with opportunities for the entrepreneur and the innovator. If you’re either, you’ll read between the lines of what these economic literati have to say, and visions may start to materialize in your own crystal ball.

The year starts with some key economic metrics that will frame where we go from here:

• The nation’s most recent official unemployment rate stood at 5.0 percent, but the Kansas City area, by comparison, fared even better: 3.9 percent. The rate in Kansas was 4.0 percent; Missouri stood at 4.7 percent—each better than the national average.

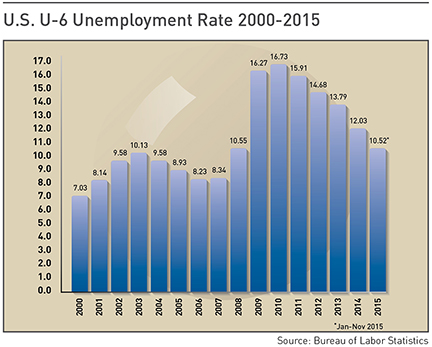

• Less encouraging was the U-6 unemployment rate, a broader measure of joblessness that accounts for labor participation rates. Nationally, it stood at 9.9 percent at latest count, well down from the peak of 17.1 percent in May 2010, but far worse than the U-3 rate of 5 percent would suggest.

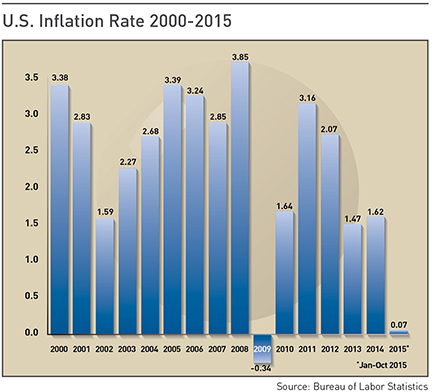

• Inflation-adjusted oil prices, with new supply driven by the U.S. fracking boom, have plunged to levels not seen since 2002; when the nation was still fighting off a post 9/11 downturn. With gasoline down an average of 93 cents a gallon nationwide in 2015, that was the equivalent of a $136 billion annual tax cut.

• Driven by those lower energy prices, the nation’s inflation rate was on track to come in below 1 percent in 2015, less than half the annual average of 2.3 percent for the preceding decade.

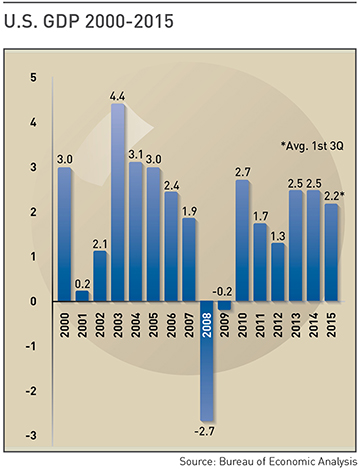

• Real GDP growth through the first three quarters of 2015 averaged 2.2 percent, even with a 3.9 percent spike for the second quarter. Unless the fourth quarter produces a monster rebound, 2015 will be the ninth straight year with less than 3 percent GDP growth.

• Nationwide, consumers were considerably more confident at year-end than they were at the start of 2015. The Conference Board’s U.S. Consumer Confidence Index stood at 92.6 in December, sharply higher than the 77.5 reading in January.

So much for the rear-view mirror view. What lies ahead?

Consider this number: 2,571. That’s the number of days between Dec. 16, 2008, when the Federal Reserve set its federal funds rate to near zero, and Dec. 17, 2015, when it make the next tick upward, targeting a range of 0.25 percent to 0.5 percent. If you’re an investor, that foreshadows another year of potential losses, given that even a low rate of inflation would easily outstrip returns at that level.

Fortunately, most investors don’t have to rely on savings accounts or certificates of deposit to secure a return on their portfolios. And it’s not enough of a bump in rates, many economists say, to derail a recovery that continues to be spotty. While some sectors, such as construction, have rebounded nicely, there’s enough collective drag on the economy to invite speculation that a recession might loom as 2015 drew to a close. Generally speaking, though, people paid to track the Fed’s movements don’t anticipate big shifts in rates to come this year.

Dan Heckman, of US Bank Wealth Management in Kansas City, said “2016 will shape up to be a very interesting year for both interest rates and capital markets. We believe there will be at least two Fed interest rate increases next year.”

The greatest risk, Heckman said, is for short-term rates to continue ratcheting upwards. Longer-term rates, he said, would be “hinged to economic growth in an environment of low inflation for the first three to six months of 2016. We also believe higher volatility is the new norm for equities after a long period of low volatility.”

Joe Haslag, an economist at the Univer-sity of Missouri, believes as well that rates aren’t likely to nudge much higher in the short term.

“I think rates are going up during the year, short-term rates, but I don’t see a whole lot of movement, and the Fed action seems to be following, rather than leading,” Haslag said. “If we’re going to get out of this low-rate environment, it’s not going to happen in leaps and bounds, and I see no evidence to support the view that returns on CDs are going to be above 1 percent.”

The upshot for him is that “we’re probably looking at decent but not extraordinary growth,” Haslag said. “My guess is 2 to 3 percent for the year. If I had to pick a number, 2.5 percent. I don’t see cause for it to be much faster than that.”

Haslag, however, doesn’t see a call for invoking prospects of a recession.

“There are risks,” he said, “but I’m not a firm believer in the camp that we’re teetering on the edge of another recession.”

Noting the Fed’s December move, Jim Huntzinger, chief investment officer for Bank of Kansas City parent BOK Financial, said, “I would anticipate that trend will continue through 2016,” with two additional rate hikes this year. “The Federal Reserve’s own expectations are for four hikes,” he said, but “I just don’t think the economy will be strong enough to allow for four rate hikes. The rate rise will be modest, so the impact on the economy, at least for 2016, should also be modest.”

At Topeka-based Capitol Federal Financial, chief financial officer Kent Town-send thinks the Fed rate could hit 1 percent by year-end. “I don’t believe longer-term rates will move up much,” he said. “I think they believe in their own forecasts. The indicators for a growing economy are mixed and a gradual increase in short-term rates that is truly data-dependent is best.”

In any case, Haslag delivers a large grain of salt to help season the views of what the Fed’s potential moves might mean.

“The Fed is a big and important player, but his view that they control the interest-rate world doesn’t jibe with

history,” he said. “It seems like they make moves after the markets have taken in their agenda adjustment.”

One of the great riddles of macroeconomics, at least to anyone who works the business end of a gas pump these days, is that the cratering of oil prices since mid-2014 is producing a drag on the economy. After all, when oil shocks hit and the price spikes, markets have conniptions about the potential for slower economic growth as a consequence.

Huntzinger provides some insight into why that view finds acceptance. “Lower oil prices have been a negative influence on the U.S. economy so far,” he said. “The reduction in spending for all kinds of services and certainly capital spending for new projects are having an immediate negative impact.”

For consumers, he said, the positive impact occurs over a longer time period. “So, we are seeing the more negative influences hit first, and the upside will happen with a lag. Obviously, energy-producing states will have more economic problems than consuming states until prices stabilize.”

The consumer lag, said Dan Heckman, could wrap up by this summer. “The benefits to consumers of lower energy prices are likely to appear over the next couple of quarters,” he said. “Initially, we believed consumers increased savings, perhaps out of concern that the low prices were temporary. After more than 12 months of lower prices, consumers may increase their rate of spending relative to their income.”

The economic boost, Heckman said, may be short-lived, since spending does not take place in a vacuum. “Consumers are now facing significant, increased costs in other areas such as health care and rent,” he said. “Regionally, low oil prices have a major negative impact for a number of Midwestern states, such as Oklahoma, North Dakota, and Colorado, all large players in shale production, in addition to hurting some of the large engineering players involved in energy-related projects.”

It’s also important to note, he said, that on a regional level, the decline in agriculture prices and farmland were having bigger local impacts than the decline in oil prices.

Townsend, too, sees the potential for any consumer windfall to be wiped out by other rising costs.

“Nationally, lower oil prices would appear to be good for our economy because it should give people the financial resources to purchase other products,” he said. “However, with the increased costs of health insurance and data indicating that consumers used the marginal increase in personal cash, resulting from lower gas prices, to eat out and go to movies, the lower prices are not resulting in increased purchases of durable goods, which would help manufacturing.”

On a local level, he said, “lower prices mean fewer jobs and less investment, which means less manufacturing to produce infrastructure goods. Overall, I believe that having reduced costs for a single commodity—as big as oil is—does not translate into a boon for the U.S. economy.”

Haslag isn’t convinced that oil prices will be much of a factor either way. “This was a big fad during the ’70s,” he said. “Economists always ran to see the effect of an oil embargo in ’73 and ’79. We had recessions that followed upticks, and oil is a ubiquitous input in production processes. I would contend that oil prices reflect some other fundamental that we can or can’t observe.”

In his view, oil itself is neither a drag nor an impetus causing anything that results in faster economic growth, and to think that it does, he says, “misses the point that the economic system is really complicated.” Higher energy prices after the Arab oil embargoes were more about the uncertainty of the world than the price of oil price per se, he said.

“The whole Iranian crisis created uncertainly about where we were politically,” he said. “Iran looked like a flashpoint for the old U.S.-Soviet divide. The world hates uncertainty, and we had a recession. But oil didn’t cause that; it coincided with that.”

Ask almost anyone how events outside the U.S. will shape the domestic economy, and most conversations start with one topic: China.

“China has slowed and there is still concern that more downside is possible,” Huntzinger said. “At this point though, the Chinese economy appears to be OK—slowing, but not in freefall.”

For Townsend, the issue isn’t grounded in the fundamentals of the Chinese economy; it’s a lack of confidence that we know what those true fundamentals area. “I think we have a problem with trusting their data, and the announced strategies to clean up the economy and overbuilding do not seem to align with economic goals stated for the country,” he said. “China may be a drag on the international economy for several years.”

Heckman said a major concern is the decline in global trade, and that’s where China looms large. “Weakness in domestic economies can cause countries to become more protectionist and draw inwards to protect their own industries,” he said. “This will especially affect China as a major exporter. As a result, China recently devalued the yuan to make their goods even more competitive in the global marketplace.”

The South China Sea, where the Chinese, Japanese, Taiwanese and U.S. are jostling for position, influence and ability to project either economic or military power, will be something to watch, Haslag said. But more broadly, “what we’re seeing in the Chinese economy are fundamentals that they still have to work out in their hybrid socialist/capitalist economy,” he said. “If they got more belligerent and aggressive with their military, that could create some issues. But with demand, they’re still working things out. Relatively speaking, it’s a huge economy with 1.2 billion people, but it’s a pretty poor nation. They’re not as poor as a generation ago, but their GDP is still around $2,000 to $3,000 per capita—not even close to what we see in advanced economies like Japan, Canada and the U.S.”

Half a world away from China, Town-send sees trouble, too. “Europe has low and negative interest rates, which would tend to boost the strength of the dollar, which will hurt our exports,” he said.

But troubles there aren’t merely economic, they’re cultural, political and demographic, Heckman said. “For Europe, the recent terrorist attacks are a concern for tourism,” he said. “Europe also suffers from poor demographic trends, with rapidly aging populations that cost considerable sums to support. Major reforms are needed in Europe in addition to more monetary easing from the ECB.”

He does, however, see some potential recovery there, despite the short-term challenges. “Europe has very modest growth, less than the U.S.,” he said. “One major difference is that the European Central Bank is still easing, interest rates are extremely low (negative in some countries), and in the middle of additional quantitative easing programs. In the U.S., we are slowing our quantitative-easing programs and have started modest interest rate increases. Europe seems stable, with a significant amount of stimulus in the pipeline.”

Recent headlines about the flood of refugees pouring into Europe create more of the same uncertainty that Haslag cautions about. “This is where risks come in,” he said. “I think what’s happening with the whole Mideast-European migration, what uncertainties that creates—I think it could disrupt international trade a great deal.”

Turning back to domestic issues, Townsend looks at some of the generational shifts taking place, and he is not encouraged by what he sees.

“Workers over the age of 65 continue to work, and that is a growing work-force cohort, which puts some pressure on the ability of younger workers to get entry-level or higher-paying jobs,” he said. More people under the age of 35 are living at home than ever before, he said, and growth in multifamily housing continues, while the purchase of new homes is largely unchanged in 2015 over 2014.

“These factors, along with others like student loan debt and delayed household formation, would indicate Millennials entering the work force will not be making the kinds of purchases my generation did, like buying houses and starting families,” Townsend said. And that, he said, means “they are not contributing significantly to growth in the national economy.”

Despite impending retirements among the Baby Boom generation, Heckman believes that it will be harder to find jobs for Millennials. While, as a group, they are well-suited for the changing economy, he said, “it’s technology that will have a major impact on the number of workers needed—we simply don’t need as many due to automation.”

For him, a bigger issue in the short term is a widening gap between skilled and unskilled labor, which argues for greater emphasis on job training and providing an environment that supports both new and existing businesses.

“There is a real lack of skilled labor in many major industries such as construction, which has such a huge multiplier impact on the economy,” Heckman said. “The skills gap, in our opinion, is holding back the real growth potential of the U.S. economy and requires further action both by private and public institutions.”

Townsend also cited the complexity of federal regulation as a continuing drag on the economy, “whether it is in health care, banking, manufacturing or environmental areas.” He’s also concerned that stocks may be near a peak in value, and if they continue the swoon that market year-end and early January, that could dampen consumer optimism and, subsequently, spending.

“While I am not certain the unemployment rate will drop much more,” he said, “I don’t believe it will rise, either, unless many people decide to re-enter the work force.” At this point, he says, “there seems to be little wage inflation, which tends to reflect some excess capacity within labor.”

A final variable, Haslag noted, will be the buildup to Nov. 8.

“The election is going to be a big deal,” he said. “I think you’ve seen a very activist executive branch over the past seven years, and the budget issues that came along with that—it’s going to be tough to grow our way out of the debt accumulated, over the past 10 years in particular. There are going to be some fiscal ramifications.”