HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

On one hand, today’s investor must feel like a kid in a candy store, eyes wide open with all the potential choices—individual stocks, bonds, mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, precious metals, consumable commodities, energy plays, angel and venture-capital possibilities . . .

The complexity and inter-connectedness of those choices is staggering, and only the stout of heart would risk venturing into some of those combat zones without a small army of trusted advisers as back-up. And the task for all is no easier as mid-2015 approaches, where we find that:

• The Dow Jones Industrial Average isn’t far off its historical high of 18,312.39 and hasn’t had a major correction in six years.

• 10-year treasuries are still throwing off yields of roughly 2.4 percent and have only cracked the 3 percent mark on two trading days in the past four years.

• Gold is down nearly 40 percent from a 2011 high.

• Oil is less than half its price a year ago, taking the prices of other energy sources down with it.

• And grain commodities are taking a beating.

Those are just a few of the mileposts along the current investment highway. What to make of them? Ingram’s turned to professionals from a wide range of investment disciplines for some guidance, and their answers could prove useful for those taking mid-year stock of their portfolios.

by Brad Scott

The plain fact is, the world is seeing economies advance at unprecedented rates, bringing more people out of a poverty-level existence than at any time in human history, and making them full members of thriving economies. And where local and national economies boom, markets do so, as well. Should you be a part of the action there, as well?

“Decades ago, it may have been enough to invest only in U.S. companies, but today the opportunity costs are much greater when investors ignore global opportunities,” said Brad Scott, Kansas City market leader for The Private Client Reserve of U.S. Bank. “As more economies emerge on the global scene and continue to mature, opportunities abound as they build out infrastructure, education and modernized essential services, eventually expanding to more diverse consumer and service economies.”

Foreign exchanges, he said, tend to function in similar ways, acting as central marketplaces where companies can attract investment capital to fuel their growth. “The principal risks from a U.S. investor’s standpoint are currency fluctuation, geo-political conflict and different regulatory environments—or lack thereof,” Scott said. “Additional risks are a lack of liquidity on many exchanges and foreign taxation.”

The problem for domestic investors here is having the information needed to make informed decisions, which can challenge even the professional investor.

“When considering international investing, you have all of the complexity of domestic investing and the additional burden of currency risks, geo-politics, varying global accounting standards, cultural differences and vastly different regulatory bodies that may not protect the interests of the investor,” said Timothy Dreiling, who works with Scott as a senior portfolio manager. “It’s worrisome to think of an individual investor going it alone when investing directly in a foreign company.”

Both recognize that a growing global middle class presents real opportunities for investors as other nations build out and modernize infrastructure. “It’s an exciting opportunity that could last decades,” Scott said.

Dreiling pointed out, though, that risk of geo-political conflict. “Over the last several years, global economies have been struggling with recession and deflationary pressures, which have dampened economic growth,” he said.

In addition, many developed economies are facing troubling demographic trends that will manifest themselves for decades—as with sharply declining birth rates in long-time economic powerhouses like Germany and Japan—that may prevent them from being both globally competitive as consumers and producers of goods and services, he said.

by Doug Hammer

It’s been a great ride for stock owners over the past few years—but is the ride over? With the Dow moving from a 2009 low of 6,443 in March 2009 and soaring past the 18,000 mark this year, it’s a question worth pondering. As of this month, the Dow is not far from that peak, but the investor who is in tune with market history knows that we’ve already defied historical probability.

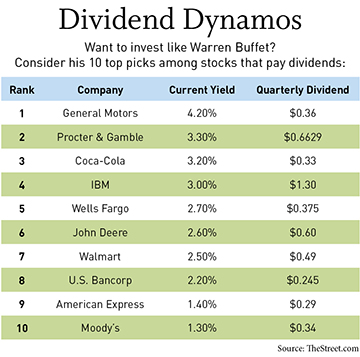

“Sometimes, the best offense is a good defense,” says Doug Hammer, a financial adviser and regional leader for Edward Jones. “The market’s up 200 percent since March 2009. Stocks aren’t as cheap as a few years ago. What we see is that earnings, earnings growth and dividends are going to play a bigger role in stock market returns in the near future.”

As is an inevitable pullback.

“We haven’t had a 10 percent correction since the summer of 2011—that’s four years, and on average, we go through about one correction a year,” Hammer says. “We forget that downturns are normal, but the other thing about them is, upturns follow downturns. And the icing on that cake is, the upturns typically last significantly longer.”

That will come as good news to millions of Baby Boomers who have failed to plan appropriately for retirement, but who are starting to see it as an inevitability, not a lifestyle choice. Not all sectors will be equally punished when a correction comes—“The things that made headlines on the way up often make them on the way down,” Hammer says—so there is still time to build wealth, even through equities.

“Is there time? The answer is absolutely,” Hammer says. “When’s the best time to plant a tree? Obviously, it was 20 years ago, but the second-best time is today.” That can still be done, he says, by embracing the Warren Buffett strategy of a wide moat. “If you think about medieval castles, that was the first line of defense. It means companies with a sustainable competitive advantage, whether that’s in their cost structure, product, distribution or brand name.”

Even amid economic calamity, he notes, consumers use diapers, toothpaste, toilet papers and other essentials, and companies making those tend to hold their ground during corrections.

The main thing, he said, is for investors to ensure that they have the proper balance in their portfolio, and equities will be only one part of that.

by Richard Boyer

When investing in stocks, it’s always nice to have a head start. That, essentially, is what you get with shares of companies that declare healthy dividends each year. The key, says Richard Boyer, of Boyer & Corporon Wealth Management, lies in the economic fundamentals that underpin a company’s stock price.

“The total return of any investment is the cash flow, plus or minus your gain or loss,” Boyer said. “With a stock that pays dividends, you’re starting out ahead a bit simply because you have cash flow. That doesn’t mean it’s not right to not own Apple, but the stock price of a company that pays a 2 or 3 percent a year dividend doesn’t have to go up much to get to a 7 to 10 percent total return.”

A story that brings home the peace of mind afforded by dividend-paying stocks, he recalls, came from his early days as a broker with Kidder Peabody. On Oct. 19, 1987, the Dow fell 23 percent, causing panic in the equities markets. Boyer called a client who was deep into ownership of Coca-Cola, AT&T, General Electric and other dividend-paying staples, suggesting it was time to get out of the market.

“He just laughed at me,” Boyer remembers, “and said I should go call somebody who needs to be called.” That investor didn’t care about the underlying stock price as much because he lived off the dividends every year, and every year, his income went up as the dividends rose. “He knew what they were going to pay, and that helped him not panic on a day when everyone else was panicking.”

When a company not only pays a dividend, but regularly increases that payout, Boyer said, investors can be assured that the company is actually earning something, and paying something back to its shareholders. Conversely, he said, it’s a red flag if a company stops raising the dividend after years of increases. “And if they eliminate the dividend altogether, that’s a black flag.” Boyer said.

by Dan Dolan

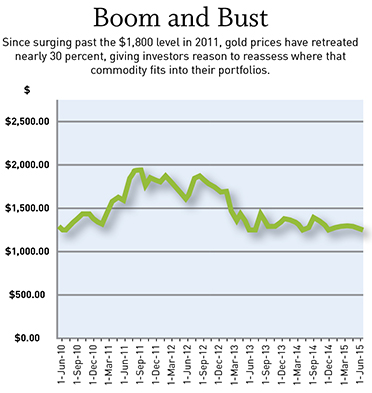

If you listen to talk radio, the ads from companies hawking gold ownership never seem to address a potential downside—today is always the best time to buy. Well, the downside came after mid-2011, when prices peaked at nearly $1,900 an ounce. Four years later? It’s less than $1,200, down almost 38 percent.

“With gold in general, it has a negative correlation to the stock market,” said Dan Dolan of Tax Favored Benefits. While gold was getting that bath, Dow Jones showered rewards on equities owners, the tune of a roughly 50% increase since gold peaked.

So it’s important to keep gold ownership in perspective and not let it crowd out other investments in one’s portfolio.

“Normally, it’s a safe haven in inflationary times, or if people see the economy or the markets heading down,” he said.

That’s usually the situation as far as why someone would consider owning gold; they hear the ads all the time. But it’s a tangible physical property, and since it has that negative correlation, it can diversify a portfolio.”

When dealing with clients who want a piece of the action with gold, he said, “I normally approach it as a trade: I’m not going to invest and own it for the next 10 years.” That’s particularly true with trading of ownership certificates, he said, but with actual gold bullion, some investors may intend to keep it for the rest of their lives.

The benefit of ownership then, “truly does vary from investor to investor,” Dolan said. “Some may decide to put X-percent into gold because they have more risk tolerance than others; some may never have a gold position their life. If an investor is jittery or worries about the volatility of the market, or doesn’t like market swings, a position in gold could be a good thing.”

It’s important, he said, to know that like any other investment, gold is cyclical. “Most of my clients don’t normally buy and then own gold for 25 years,” Dolan said. “For folks who bought at that time frame (2011), things didn’t go very well for them. Once those dollars are lost, you’re trying to find an exit, and that’s awfully hard to predict.” So within the context of most portfolios, gold should represent a small percenttage, and be purchased for the right reasons. Hopefully, you’re looking to buy low, so there’s probably not much downside.”

by A.J. Jones

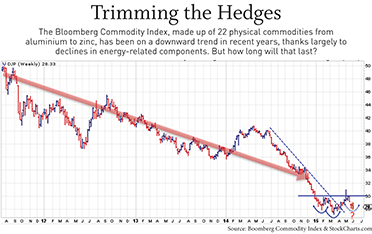

A.J. Jones speaks with a candor that’s as abundant as wind outside his office in Lakin, Kan., on the High Plains: When it comes to playing in the commodities arena, says the veteran broker for Paragon Investments, “I ask people what are they interested in trading, first of all, because you have to look at their knowledge of trading. If they don’t have it, then you don’t want to go there. Commodities are high risk and high reward. Most people don’t trade them—most don’t even know what they are.”

Commodities trading exists to bring liquidity to markets for everything from cash crops to industrial metals, from gold and silver to cattle and hogs, oil and natural gas. If you get into it, you’re either doing so as someone trying to hedge against big price swings—as with companies that consume large quantities of oil, perhaps—or as a speculator.

Either way, says Jones, successful trading starts with a good buyer-broker relationship. After that, the power of trading commodities lies in the ability of investors to leverage small sums into sizable returns, without having to take physical possession of a train car of sugar, for example.

Take cattle: At current prices, $100,000 wouldn’t buy a lot of meat on the hoof, but the same amount in cattle futures can allow you to control the fates of a far greater number of animals. “It’s leverage, it’s liquid, and it’s easy to get in and out; you don’t have to own it forever,” Jones said.

It’s important to be able to put all the pieces together to successfully trade, Jones said. In today’s commodities climate, informed investors know that cattle prices are at all-time highs, in part because of extended drought in the beef-grazing lands of the Plains. The past two months of drought-busting rain in Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas could replenish both grazing grassland and ranch stock ponds, creating conditions where ranchers might want to have more cattle to market so they can cash in on the high prices.

Jones suggests that commodities should represent 5 to 10 percent of an investor’s portfolio, depending on risk tolerance.

by David Neihart

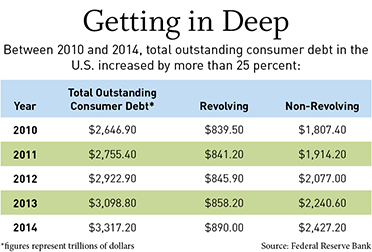

Paying attention to the growth of one’s portfolio is always a good practice, but too many investors, says David Neihart, are focusing on the size of the boat, and ignoring the anchor that’s dragging down overall wealth-performance: Debt. There are three good reasons to cut the chain, said Neihart, of Wells Fargo Advisors.

“First, the obvious, it adds risk.

The second thing—and it was less known until 2008—is that it requires liquidity to address. If you need cash to make a payment, and if you’re in an environment where prices are down and there’s not much liquidity, you may have to sell something at a loss to cover that. Nobody thought much about liquidity until 2008, and if that liquidity is not in place, you can be very surprised.”

The third risk stems from the prolonged low-rate environment. Too many investors have simply stopped recognizing the potential exposure to loss of wealth if rates start rising significantly. “With rates so low for so long, it’s been easy to get lulled into a sense of complacency,” Neihart said. “To many investors, it’s almost inconceivable that rates could rise any time soon. They don’t pay attention to the debt side of the balance sheet as they think that’s not going to change much.”

When everyone says don’t pay attention to the threat of higher rates, he cautions, it’s probably a great time to pay extra attention.

It’s also important, he said, for investors who are carrying debt to understand how much of that interest is fixed, and how much is variable. “There’s a lot of variable out there, because that’s where people get the very low rates, and those are very attractive.”

We’re now in year Seven of a low-rate environment, he noted. “That’s a long time. Historically, rates go up, they go down, but this is an inordinately long period of time with straight-line rates and low volatility. Now, I can’t point and say it’s about ready to change, but I think books will be written in the future about how low rates are today.”

Nearly half a generation of investors have known nothing but low rates, which can lower the sense of urgency to address debt, with potentially painful consequences. “After seven years, surely we’re closer to the end than the beginning of rates rising, even though I can’t give you a set economic indicator,” Neihart said. “That’s been proven over and over again.”

“The best strategies start with having a plan. If that debt isn’t paid off at low rates, the benefits of acquiring it will be diminished. The whole concept of coming up with a repayment plan has gone by the wayside,” Neihart said. “Any time you have debt, you think you have a plan, but it seems like it has become more and more vague. What business would borrow money without a model that says, ‘Here’s our repayment plan, with a specific objective’?”

by Rebecca MacKinnon

In traditional investing, most professionals counsel against letting emotions get in the way of decisions about when to buy or sell. But with angel investing—where an investment is being made in the very early stages of a company’s life—one emotion should be at work, says Rebecca MacKinnon: Passion.

“You have to fundamentally be a dreamer and see a world that could exist in the future,” says MacKinnon, a serial entrepreneur who’s a key figure with Mid-America Angels, an investor group. “You let your interests and your passions guide you in determining which deals would be the right deals for you.”

Kansas City, as a region, is blessed with assets that promote entrepreneurship and a start-up mentality, and that’s paying off for both the innovator and the investor. “I think there are some really good resources available to help prospective angels start to understand the process,” MacKinnon said. “And understanding the eco-system of capital is really important, because angels are an important part of that ecosystem.” So too is “recognizing the value of the capital at risk, knowing about how the timing of a deal impacts an investment, and the economics of how companies grow on the capitalization schedule,” she said. “All of those are important in getting comfortable with making your investments.”

But the contribution doesn’t stop when the check is written. “The last part is investing in yourself,” MacKinnon said. “Young companies grow not just because of money and skill, but networking. As you grow in your own career and reach a certain amount of success, we all have networks we can bring to the table and help these companies find legs. Networking provides key relationships that can help move them forward. That’s one of the most valuable roles the angel can play.”

Thanks to organizations like the Kauffman Foundation and other efforts to promote entrepreneurship, the region is far more vibrant with angel investing than it was a decade ago. “I think we deserve great accolades for the network we’ve built over the last decade,” MacKinnon said. The next step as a community, she said, would be for the region to embrace other pieces of the capital system, such as venture capital. “Kansas City was never really strong with venture capital, but we’re seeing buds of interest and real players starting to form capital in that space.”

by James Battmer

After a lifetime of wealth accumulation, investors are looking for some peace of mind, some insurance policy against an unforeseen calamity. As a practical matter, diversification of a portfolio is one way to provide that insurance and that solace.

Another, notes James Battmer of Bukaty Companies, is insurance itself.

“What we look for in the portfolio management component is a low to negative correlation between the different assets,” Battmer said. “You traditionally do that in a portfolio by diversifying across many different asset classes. When looking at the larger wealth plan, it’s about making sure people are covering themselves against the worst possible scenarios, and without insurance, that can only come at the point where someone is able to self-insure.”

The challenge for investors, Battmer says, is the same one Mark Twain identified when he said “an insurance salesman sells you an umbrella, and asks for it back when it rains.”

“Too many times, I’ve seen individuals think that they have dotted the I’s and crossed the T’s, thinking they have full comprehensive coverage with long-term care, and when they went to use it, found out there was some delineated note in the fine print that made their circumstance un-viable.”

Read the fine print of any policy that exists to defend against loss of wealth, particularly those being marketed for long-term care these days. With nearly 75 million Baby Boomers bearing down on age 70 and blowing past the retirement age of 65, more opportunities will exist for policies that are almost guaranteed to disappoint.

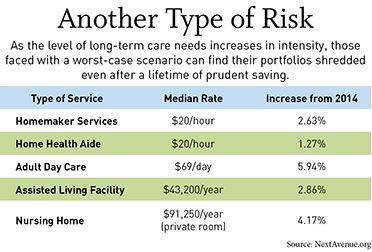

“People also need to make sure that they’ve done their due diligence so that they’re not paying a premium that’s not going to cover them when they actually need protection,” Battmer says. “We see a lot of clients who pay for long-term care—which is often the gap in a comprehensive wealth plan—their insurance is in place, their assets are fine, it’s all sustainable and appropriate. But if you’re gravely sick and live 10 more years in that condition, that’s when we really start to see stress on the portfolio.” In extreme cases, that could mean charges of $10,000 to $15,000 a month in a full-service care facility.

by KC Mathews

Given where we stand in the current economic cycle and investment climate, where are the looming investment traps?

“I would say more on the interest-rate side of things,” says KC Mathews, chief investment officer for UMB Bank. “We do think rates will rise by the end of the years, and we’re forecasting 2.5 percent—the other day, it was at 2.4 percent, so that’s one area where investors have to be cautious.”

With the bond market, he said, investors may think they’ve minimized their risk exposure. Recent events have disabused many of that notion. “Look back to January of this year,” he said. “The 10-year Treasury, if you bought then, you’ve lost 7 percent of the value. If you bought the 30-year, you’ve lost 18 percent.”

Granted those are treasuries, and owners can hold onto them for those 10 to 30 years to avoid taking those losses. But that, too comes with a cost, Mathews said. “You can hold them and you won’t lose money, but you may lose other opportunities.”

Volatility in the bond market, he said, is likely to stick around for a while, much to the chagrin of the many who fail to appreciate that potential. “We’re going to be in a period where rates will probably rise and you’ll have a strong dollar, given what’s going on in Europe and the rest of the world,” he said. “When our economy is growing moderately, rates will be rising moderately, and the rest of the world will still be in an easing mode.”

That would continue to put pressure on the Dow, where the impact of rising rates will present additional investor concerns. “One of the things about the risk in higher rates for bonds is that it trickles into other interest-rate-sensitive areas. When you look at real-estate investment trusts, those are rate sensitive and could be a yield trap, where investors are still looking for that return, especially retired investors. They see movement or that their REIT’s not performed that well, but it’s tough to catch a falling knife.”

Given current price-earnings multiples for equities, running around 16.5 times forward earnings, and considering the strength of the dollar, there are investment headwinds. But he thinks returns of 2-3 percent are reasonable, and if some revenue growth occurs on top of that, or factors like mergers and acquisitions break an investor’s way, a total return of 4-6 percent is possible this year.

But the overall strategy, Mathews said, should be grounded in a full understanding of each investor’s risk tolerance.