HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Nearly a generation ago, Ingram’s launched the Top Doctors recognition program to spotlight the best of the hands-on physicians who made up what was then—and still is today—regarded as a highly sophisticated medical community for a metropolis of this size.

But in a metropolitan area of 2.2 million people, with thousands of physicians, how do you determine the best? Each year, a growing alumni base adds fresh perspective to the candidate field, which is one way we compile a stronger list of potential honorees. Whether they’re new to the process or first-year recipients of the Top Doctor designation, all are asked to address one question: If you or a loved one needed the best medical care available in this market, which physician would be your choice for that care?

It’s a clarifying question, one that cuts through allegiances to physician practices or affiliated hospitals, and one that helps us determine a field of Top Doctors who are both representative of the Kansas City health-care marketplace as well as their own profession.

This year, that call was answered by nominations that produced a field of specialists in cardiology, oncology, pediatric medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, surgery, urology, pulmonology and gastroenterology—10 physicians, we’re confident, who would bring the highest levels of care, compassion and competence to your own bedside.

Next year, we’ll celebrate the 20th installment of Top Doctors, adding one more class to an alumni group that now number slightly more than 200. Time marches on, and among them, many have retired, some have left Kansas City for others markets, and, sadly, some have passed on.

Those who are still active, though, represent the finest in what this region has to offer to enhance not just our quality of lives, but at times, the very duration of them. Please join us in a salute to Ingrram’s 2015 Top Doctors, and all those who have earned this impressive recognition before them.

In a childhood home with six boys, Gary Doolittle recalls, “somebody was always sick or breaking something,” which would occasionally result in a house call from the family physician. “He was amazing,” says Doolittle, an oncologist and medical director for the Midwest Cancer Alliance, the outreach arm of the KU Cancer Center, of which the University of Kansas Hospital and hospital systems across the state are members. “I can’t tell you the first time I remember wanting to be a physician, but I do remember I wanted to be like Dr. Landers.”

Doolittle was raised in the Philadelphia area, by parents who hailed from Kansas City and Wichita, and he earned his medical degree from KU’s medical school, “so I consider myself a Kansan as much as anything,” he says. And that’s good for skin-cancer patients across the state, because he also is medical director for the hospital’s Center for Telemedicine and Telehealth. In those various roles, he’s researching and treating cancer, particularly malignant melanoma.

That specialization came along after a 2000-2001 sabbatical at the University of Queensland, an Australian state with the highest incidence of melanoma in the world. Unlike cancers that are associated with aging, melanoma presents particular challenges in that it can be seen throughout the human life span. Research, though, is changing the field dramatically. “We understand the biology of it in ways we did not understand 10 years ago,” Doolittle says. “Once we understand what causes a cell to grow abnormally, we can figure out a way to control it.”

The biggest advances toward that goal entail the use of immunotherapy, using agents to stimulate the body’s immune system, helping activate it to seek out and kill melanoma cells, Doolittle said. “That’s been remarkable. Some of the new agents are really remarkable in their affinity for melanoma, lung cancer, and bladder cancer—diseases traditionally not easy to treat, but ones that are responding to these immunotherapy drugs.”

Her first venture into the operating room at Memorial Hospital in Niagara Falls, N.Y., came when Michelle Dudzinski was just a candy striper. But already, she knew what she wanted to be. “I was always very comfortable in the operating room,” says Dudzinski, a gynecologic oncologist with Shawnee Mission Health, even just sterilizing instruments or fetching X-rays as a teen.

She’s one of a comparative handful of physicians in the region who treat cancers of the female reproductive system, a niche she felt called to early, but one she couldn’t get to without first obtaining certification as an OB-GYN. “I wanted to primarily be a surgeon, and I really enjoyed taking care of women, then I found out I had to do Ob-Gyn to become a gynecologic oncologist.”

That work, she says, is “the only specialty where we actually take total care of the patient. We make the diagnosis, we do the surgery and we also do the chemotherapy. There’s no other specialty that provides complete care for the patient in that way. It’s total continuity for patients.”

In 1992, she left a faculty position at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, seeking the ideal setting to raise her daughter, then 9 months old. Kansas City, she decided, was that place. In the 23 years since, Dudzinski has treated patients in this area and witnessed powerful innovations in treatment of gynecological cancers. “Just tremendous advances,” she says. “When I started, there were basically only one or two chemotherapy drugs to treat ovarian cancer. Now we have 10-15 and new innovations in chemotherapy and surgical practices are occurring daily. Not only have survival rates improved, but even if patents are not cured, the length of time they live has dramatically increased,” she says. A side benefit of her work is that “many of these patients have become friends of mine,” she says. “When you provide total care to a patient from beginning to end, they become your friends, and many have become lifelong friends.”

Back in grade school in his hometown of Beirut, Rony Abou-Jawde might not have been able to describe in detail what it meant to be an oncologist. But he knew at his core, even then, that he could become a soldier in the global war on cancer.

“Since first grade, I always knew I wanted to be a cancer doctor,” says Abou-Jawde, an oncologist with Mosaic Life Care in St. Joseph. “I grew up with two very close family members with cancer, and I saw them go through their treatments and decided I wanted oncology as a carrier.”

That conviction played out at American University in Beirut, with a degree in biology, then medical school there. He came to the U.S. for both his internship/residency and fellowship in hematology oncology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. There was never a doubt about his plans for specialization. “Seeing my own family going through cancer diagnosis and treatments and what they went through made me want to become an oncologist to help cancer patients as much as I can,” he says. “In some way, I understand what they are going through.”

So it was particularly moving when a young mother showed up at his office with her children in tow, asking for his help. She had been told she had only six months to live. It’s gratifying, he says, to think that “you are able to pick a treatment for her and now see her fully functional and in excellent shape seven years later. … Seeing and sharing this journey with her makes it all worth it.”

And it’s more rewarding than ever to be armed with the kinds of innovations that have been brought to bear on the cases he treats. “The last three to four years have seen the most important advances and innovations in the field of cancer diagnosis, and treatments,” Abou-Jawde said. “Starting from personalized cancer genetics to targeted chemotherapy to the new immunotherapy treatments for usually hard-to-treat cancers.”

Even with all the changes and challenges in medicine, he says, “it is still a great career and a humbling career, and I surely urge my twin daughters to pursue medicine.”

More than 30 years after Alan Gamis earned his medical degree, his choice of a career in health-care is reaffirmed almost daily. It happens, he says, “every time a child comes running up to give me a hug, or a parent thanks me or cries on my shoulder, or when I receive a card announcing one of my old patients graduating from school, getting married, or announcing a birth of their child. Those are the moments that give me strength.”

Gamis is the associate division director for hematology and oncology at Children’s Mercy Hospital, is a native of Peoria, Ill., who finished medical school at the University of Illinois’ College of Medicine, and later earned a master’s in public health epidemiology from Minnesota. But when he came to Children’s Mercy for his residency, he found a home.

“In my research career, I have contact and see many leading centers around North America and Europe,” he says. “I have yet to find another children’s hospital which has such great clinical capabilities and staff, combined with the most advanced pediatric care and research environment available for our patients.”

That setting provides something of a bulwark against the economics of medicine, which have grown increasingly complex and burdensome for many physicians. The more that economic factors guide treatment decisions these days, the more a corporate mentality seems to insert itself into health care, he notes. “I guess that is why I like working at Children’s Mercy,” Gamis says, “as no matter the problem, no matter the cost to the hospital, and no matter the logistical difficulty, the philosophy is always the same: What is best for the child?”

That approach often leads to happy outcomes, but physicians in his area of specialization know that no matter how many victories are celebrated, losses are unavoidable. Says Gamis: “The times when I must sit with a family who has lost a child to cancer are the ones that continue to give me the passion and drive to find new and better ways to treat cancer in these young patients.”

Being a native of Mason City, Iowa—home of the playwright who penned “The Music Man”—it wasn’t preordained that Tomas Griebling would develop a love for music as a boy. But it was a safe bet, and he learned to play piano, flute and piccolo. High school brought new interests in biology and chemistry, and a curiosity about medicine. Which path to choose? “I had to make a decision: Music or medicine,” he remembers. “I realized I could still enjoy music and play and perform if I went into medicine, but not the other way around.” Medicine it was.

He majored in biology, chemistry and sociology at Wartburg College in his home state, then attended medical school at the University of Iowa. And that’s where he met a patient who would help set the stage for his career in urology. “She was in her early 90s, very fit, active and cognitively intact—very sharp,” Griebling recalls. “But she really didn’t get out of her house because of incontinence.” He performed a minimally invasive procedure, and six months later, she came to him to tell him that not only had she made it out of the house, she’d taken Amtrak to California to visit her children, something she never would have done before the procedure.

“Seeing that type of impact on people’s lives was a big factor for me,” says Griebling. Urology, he said, entails a focus on a very limited anatomy and physiology, but encompasses a lot of other medicine and different types of surgery. “Urinary incontinence is one of the most common diagnoses I see,” he said. “If we can make an improvement for people, we can really change their lives.”

After his training, Griebling had opportunities to go almost anywhere, but chose Kansas City because he could obtain an academic position. KU offered the prospect of work in both urology and geriatric medicine. “I wanted to be at a place with strengths in both,” he says. The graying of America promises no shortage of patients in the years to come. “I do a lot of speaking and teaching at the national level,” Griebling said, “and when you look at specialties, excluding pure geriatrics, of all the other specialties, urology consistently ranks in the top three in the number of older adults cared for.”

At the intersection of medical treatment and the business of medicine, you will find Ken Huber—directing traffic. A cardiologist by training, he’s the chief executive for Saint Luke’s Cardiovascular Consultants, a partnership formed in 2009 between the health system and the cardiology practice where Huber was serving as president.

While still serving as a consulting cardiologist, Huber currently holds more than a dozen leadership positions through the practice group and Saint Luke’s Health System: he’s president and CEO of the cardiology group, a member of its board of directors, and chairman of its physician leadership group. His work helped Saint Luke’s heart and vascular program earn recognition from U.S. News & World Report, which earlier this year named it among the Top 20 cardiology and heart surgery programs in the country.

Huber is also a member of the health system’s strategic planning council and a member of the system’s management council. He sits on the system’s executive leadership team and he’s co-executive medical director for Saint Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute, a member of the foundation board for Saint Luke’s Hospital, and director of the cardiac catheterization lab for the heart institute and the health system, among other duties.

His contributions to academic medicine and research cover 55 articles and abstracts published since 1989, the year before he joined Cardiovascular Consultants. He’s a highly sought speaker on cardiology issues, he’s also currently involved with 17 clinical trials, and has taken part in more than 50 others that were completed. He was also part of the evaluation of a device called the Watchman, a heart implant that can reduce the risk of stroke for patients with atrial fibrillation, and sat on the FDA panel that approved its use.

A graduate of St. Olaf College in Minnesota, Huber earned his medical degree at St. Louis University School of Medicine. And at the Mayo Graduate School of Medicine, where he did his residency and fellowship, he won the Sydenham Award for excellence in clinical history and physical examination skills.

As a general surgeon, Patrick McGregor is one of medicine’s utility infielders—you can find him at work in breast care, in colorectal surgery, performing appendectomies, repairing hernias or removing gall bladders, or using trauma expertise to correct the mayhem that is visited on patients every day.

General surgery has benefitted immensely from medical innovations since he earned his medical degree from the University of Kansas Medical Center. “I enjoy that it is a procedure-based field and that problems are able to be solved quickly,” McGregor says. “I like the physical challenge of actually performing a procedure. I have particularly enjoyed the advances seen in robotic surgery over recent years.”

The advent of minimally invasive surgical techniques, including laparoscopic and robotic surgery, he says, “have enhanced patient outcomes and recovery. I have embraced new technology in the surgical field as I’ve seen the benefit to my patients.”

And among them, there’s a special place in his heart for young patients. “My work is particularly meaningful when dealing with young people who have been involved in a traumatic accidents who without surgery, would not survive, and then seeing them restored to health, able to resume a normal life,” he says.

He grew up in Wichita, and his family moved to the Kansas City area not long before he went to high school. So after earning his M.D., it was a logical choice for his career. “My wife and I both grew up in Kansas City and loved our hometown,” he says. “We knew it would be a wonderful place to raise our two children. We found a group of surgeons that I have enjoyed working with these last 19 years.”

His son, Cole, is a second-year medical student, and Dad says he strongly supported the young man’s decision to go into a medical career, “despite knowing the sacrifices and challenges he would face. While there are more challenges today, I feel being a physician will always be rewarding and I consider it a great privilege to serve my patients and the community.”

The mental picture, says Esmat Sadeddin, is as much in focus today as it was the day his mind captured it: One of his brothers in a family of 11 children developed anaphylaxis from a food allergy. “The picture of his doctor and nurses surrounding him and taking caring of him and comforting my parents has stuck in mind to this day,” says Sadeddin, section chief of gastroenterology at Truman Medical Center. “It was that moment that made me decide to be part of this noble profession.”

So after wrapping up medical school in his native Jordan, he came to the United States and spent time in Missouri’s two largest cities, honing his skills in internal medicine and gastroenterology through UMKC, and mastering therapeutic endoscopy at Washington University-Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

At that stage of his training, gastroenterology provided a unique appeal as a specialty because it combined both the medical and surgical aspects of patient care, he said. And armed with current versions of the tools used in endoscopy, he’s able to take what amounts to a tour of the human torso from the inside to confirm a diagnosis and administer treatment, whether that entails performing a biopsy on a lymph node deep in the chest cavity, detecting lung cancer or removing polyps in the colon. “I truly enjoy performing endoscopy,” Sadeddin said, calling it “one of the few tools in medicine that is proven to prevent cancer.”

In the nearly two decades since he earned his medical degree, Sadeddin has seen the pace of technology increase, particularly over the past 10 years, and witnessed new vistas on what is medically achievable.

His success at work has spilled over to life in the city he calls his second home. “This great community with their big hearts and their beautiful souls made me feel that I have never left home,” Sadeddin said. “The city of the fountains is a great place to live, with a low cost of living, fabulous culture, shopping, and restaurants, it has one of the best educational system in the country and—the most important part—we have the Royals and the Chiefs.”

As a kid growing up in small-town in southern Illinois, Dennis Lawlor developed an early fascination with science fiction “and what was possible or seemed to be possible with scientific knowledge. Maybe it’s no surprise, then, that he sounds like a kid in a candy store when he talks about the science fact of tools he uses as a pulmonologist for Olathe Health System’s Consultants in Pulmonary Medicine.

“The trend towards smaller and improved imaging capabilities provides more detailed information about the anatomy of the lung,” says Lawlor. “These technologies greatly facilitate accurately assessing nearly every nook and cranny in the lungs without major surgery, (and) allow us to accurately diagnose and treat patients in ways we couldn’t even conceive of just five or six years ago.”

Math and chemistry captured his attention at Benedictine College in Atchison, but lab work didn’t have the same appeal he thought he’d find by “using scientific knowledge and working with people to improve their health and lives.” But medical school costs were a challenge, until a U.S. Air Force scholarship punched his ticket to medical school at St. Louis University. After earning his degree, he served in various Air Force settings—the military isn’t giving away med-school tuition, after all—including several deployments in Bosnia during the 1990s. Again, innovation was key to what he was doing, as new technologies advanced the understanding of and treatment of battlefield injuries.

Pulmonology offers an immediate return on a physician’s time invested with a patient. “I have always enjoyed this part of pulmonary,” he says, and “I have become much more interested in the full spectrum of care in pulmonary in the last 10-15 years, and in particular caring for patients with cancer. The ways to help diagnose and treat lung cancer with less harm, and less risk to the patient have dramatically improved during this time.”

And despite the business-side challenges of medicine, Lawlor believes the pluses outweigh the negatives, and he’s raised his children accordingly: one son is in medical school at Northwestern University, focusing on brain function, and a daughter is working on her master’s degree in speech pathology at the University of Texas-Dallas.

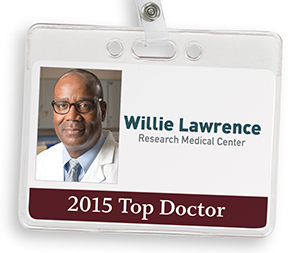

It’s a statement packed with too many social pathologies to dissect here, but it nonetheless stands out for Willie Lawrence, chief of cardiology at Research Medical Center: “When I came to Kansas City, I was the only African-American practicing cardiology,” he muses. “Twenty years later, same deal, though there is one in Lee’s Summit. There’s something wrong with that.”

Lawrence is highly regarded not just in this market, but nationwide, for cardiology generally and more specifically for his work in the sub-specialty of hypertension. In addition to his work at Research, he serves on the board of directors for the American Heart Association, which named him its Physician of the Year in 2011.

He’s a native of Cleveland, raised in a neighborhood not unlike those found east of Troost Avenue, he says. His ticket out was punched by the prestigious Phillips Exeter Academy, whose alumni list includes a pair of presidents named Bush. His interest in science grew there, particularly biology, and he went on to Harvard Medical School, then worked there for 12 years, focusing on heart and kidney research.

Coming to Kansas City was a family decision; his wife, Sandra, is now chief financial officer for Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics. Over the two decades of practice and research here, he’s embraced hypertension because, he says, it presents the “greatest negative impact” on patients. During that span, Lawrence has also dealt with the impacts of medicine’s business side, with two hospitals closing on him and a cardiology practice dissolving as some partners sought ostensibly greener pastures in suburban settings.

The phrase “move the needle” comes up often as he examines what he hopes his work has brought to the study and treatment of high blood pressure. “Hypertension isn’t sexy, but you don’t need to lower your blood pressure by much to see significant benefits to the patients we serve in all communities,” Lawrence says. “Less than half the time, blood pressure isn’t adequately controlled, even in patients who have been diagnosed with it. We just don’t do a good job treating hypertension.”

| Rony Abou-Jawde, Oncologist Raghu Adiga, Epidemiologist Mark Aeder, Transplant Surgeon Ann Allegre, Internal Medicine, Palliative Specialist Arthur Allen, Neurologist Glenn Amundson, Orthopedics Edward Andres, Vascular Surgeon Keith Ashcraft, Pediatric Surgeon Mark Austenfeld, Urologist David Bamberger, Infectious Diseases Specialist Cris Barnthouse, Orthopaedic Surgeon Kent Barr, Cardiologist James Beardman, Hospitalist Robert Belt, Oncologist Walter Bender, Nephrologist Loren Berenbom, Electrophysiologist Gary Berger, Physical Medicine/Rehab (Deceased) Irene Bettinger, Neurologist Geoffrey Blatt, Neurosurgeon David Bock, Urologist Douglas Bogart, Cardiologist Rene Bollier, Family Medicine Michael Borkon, Cardiovascular Surgeon Denise Bratcher, Assoc. Professor of Pediatrics William Brodine, Cardiac Electrophysiologist Charles Brook, Pulmonologist Jon Browne, Orthopedic Surgeon David Burkart, Interventional Radiologist Fred Burry, Pediatrician Paul Camarata, Neurosurgeon Gary Carter, Emergency Medicine Joe Cates, Vascular Surgeon Ernest Cattaneo, Internal Medicine Cindy Chang, Emergency Medicine Jonathan Chilton, Neurosurgeon Mark Davidner, Oncologist John Davis, Oncologist Marie Delcambre, Internal Medicine Richard Derman, Obstetrician-Gynecologist Dennis Diederich, Nephrologist Kevin Dishman, Internist Gary Doolittle, Oncologist Michael Driks, Infectious Diseases Michelle Dudzinski, Gynecological Oncologist John Dunlap, Internal Medicine Dan Durrie, Ophthalmologist David F. Emmott, Urologist Carol Fabian, Internal Medicine Brett Ferguson, Oral-Maxillofacial Surgeon Laura Fitzmaurice, Pediatric Emergency Medicine Scott Folk, Infectious Diseass Jameson Forster, Transplant Surgeon Brian Friedman, Cardiologist Burrel Gaddy, Orthopedic Surgeon Alan Gamis, Pediatric Oncologist/Hematologist Thomas Geraghty, Plastic Surgeon John Gianino, Neurosurgeon Douglas Girod, Otolaryngologist George Gittes, Pediatric Surgeon Glenn Goldstein, Dermatologist Michael Gorton, Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rengasamy Gowdamarajan, Pediatric Cardiologist Nathan Granger, Family Medicine Jared Grantham, Nephrologist Matthew Gratton, Emergency Medicine Thomas Griebling, Urologist Stephen Griffith, Family Medicine Trudi Grin, Pediatric Ophthalmologist Harvey Grossman, Pediatrician Dan Gurba, Orthopedic Surgeon Philip Gutek, Plastic Surgeon Robert Haas, Orthopedic Surgeon Curt Hagedorn, Gastroenterologist/Hepatologist Frederick Hahn, Jr., Otolaryngologist John C. Hall, Dermatologist Robert Hall, Neonatologist Donald Hatton, Internist Roy Hegde, Cardiologist Thomas Helling, Surgeon Richard Hellman, Endocrinologist John Helzberg, Gastroenterologist Joseph Henry, Pulmonologist Edward “Ted” Higgins, Jr., Vascular Surgeon Rodney Hill, Pulmonologist Mohan Hindupur, Cardiologist Eric Hockstad, Cardiologist Samuel Hoeper, Jr., Internal Medicine George Whitfield Holcomb, Pediatric Surgeon John Holkins, Cardiologist Frank Holladay, Neurosurgeon Larry Hollenbeck, Neurologist Jeff Holzbeierlein, Urologist Ken Huber, Cardilogist John Hunkeler, Ophthalmologist Verda Hunter, Gynecological Oncologist Mary Anne Jackson, Pediatrician Robert Jackson, Pediatrician Amie Jew, Surgeon Michael Johnston, Internal Medicine Stephen Kaine, Pediatric Cardiologist Ralph Kauffman, Pediatrician & Pharmacologist Gregory Kearns, Pharmacologist Jane Knapp, Pediatric Emergency Medicine William Koller, Neurologist (Deceased) |

Dennis Lawlor, Pulmonologist Willie Lawrence, Cardiologist Vincent Lem, Pulmonologist Lori Lindstrom, Radiation Oncologist Ted Lockwood, Aesthetic Surgeon (Deceased) Gary Lofland, Pediatric Cardiac Surgeon Michael Loggan, Pulmonologist Charles Luetje, Otologist Rodney Lyles, Reproductive Endocrinologist Anthony Magalski, Cardiologist James Maliszewski, Internal Medicine Gerald M. Mancuso, Interventional Cardiologist Vickie Massey, Oncologist Ben McCallister, Cardiologist (Deceased) Craig McClure, Interventional Radiologist Lon McCroskey, General & Vascular Surgeon Patrick McGregor, General Surgeon Joseph McGuirk, Oncologist Richard McKittrick, Oncologist James McMillen, Hospice, Pallative Care, Internist Kendall McNabney, Surgeon James Miller, Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rauf Mir, Nephrologist Randall Mitchem, Pulmonolgist Michael Moncure, Trauma Surgeon Michael Montgomery, Cardiologist Patricia Mooney-Smith, Obstetrician-Gynecologist Jill Moormeier, Oncologist Richard Morgan, Palliative Care Chuck Moylan, Pediatrician Greg Muehlebach, Cardiothoracic Surgeon J. Patrick Murphy, Pediatric Urologist Jane Murray, Family Physician Richard Muther, Nephrologist Bryan Nelson, Pediatrician Darryl Nelson, Family Physician Marcus Neubauer, Hematologist/Oncologist Kathleen Neville, Pediatric Oncologist Paul O’Boynick, Neurologist James O’Brien, Cardiovascular Surgeon Mary O’Connor, Epidemiologist James O’Keefe, Jr., Cardiologist Scott Olitsky, Pediatric Ophthalmologist Brad Olney, Pediatric Orthopedic Surgeon Steven Owens, Cardiologist Rajesh Pahwa, Neurologist Kent Palmer, Chief Medical Officer Alexander Pak, Cardiothoracic Surgeon Gerald Park, Urologist Kelly Pendergrass, Oncologist Chris Perryman, Internal Medicine Joseph Petelin, Laparoscopic Surgeon Susan Pingleton, Pulmonologist William “Pete” Pingleton, Pulmonologist Mark Plautz, Internal Medicine Henry Randall, Transplant Surgeon T.J. Rasmussen, Orthopedic Surgeon Stephen Reintjes, Neurosurgeon George Reisz, Pulmonologist Brian Robb, Emergency Medicine Charlie Roberts, Pediatric Gastroenterologist Howard Rosen, Endocrinologist Larry Rosen, Oncologist William Rosenberg, Neurosurgeon Howard Rosenthal, Orthopedic Oncologist Larry Rues, Family Physician Steve Russell, Emergency Medicine Barry Rutherford, Interventional Cardiologist Marilyn Rymer, Neurologist Nelson Sabates, Ophthalmologist Esmat Sadeddin, Gastroenterologist Stephen Salanski, Family Medicine Jeffrey Salin, Orthopedic Surgeon Gary Salzman, Pulmonologist Timothy Schmitt, Transplant Surgeon Jane Schwabe, Cardiothoracic Surgeon Fred Seligson, Cardiothoracic Surgeron Steven Simpson, Pulmonologist Shadrach Smith, Bariatric Medicine Daniel Stechschulte, Rheumatologist/Immunologist Mark Steele, Emergency Medicine David Steinhaus, Electrocardiologist Tracy Stevens, Cardiologist James Stewart, Internist/Geriatric Medicine Stephanie Studenski, Geriatric Medicine Michael Sweeney, Cardiologist Sarah Taylor, Oncologist Kim Templeton, Orthopedic Surgeon Daryl Thompson, Internal Medicine/Neurologist Mark Thompson, Radiation Oncologist Brantley Thrasher, Urologic Oncologist Terance Tsue, Otolaryngologist Charles Van Way III, Thoracic Surgeon Joseph Waeckerle, Emergency Medicine Brad Warady, Pediatric Nephrologist Jeffrey Waters, Pediatrician Michael Weaver, Emergency Medicine Charles Weinstein, Neurologist James Whitaker, Orthopedic Surgeon Steven Whitfield, Cardiologist Steve Williamson, Oncologist Sandra Willsie, Pulmonologist/Intensivist David Wilt, Internal Medicine Gerald Woods, Hematologist/Oncologist |