HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

For family-owned businesses, there are many paths to long-term success.

Anyone who’s been a part of one knows that when it comes to ownership and operations, success and succession, the family-owned business is a com-pletely different game. And it takes some special players to win this one.

The honorees of Ingram’s 2018 Family Business Awards definitely fall into that category. This year, we take a look at five companies, hailing from such varied business sectors as construction, hospitality, food service, manufacturing and com-munications, exploring how the family dynamic plays out in each of them.

No two families are exactly alike, and no two family-owned companies are, either. The road each family bus-iness takes to success, though, could become a template for others who are chasing that unique prize. It’s our hope that in their stories, you’ll find inspir-ation for your own organization.

(l-r) Mary O’Connor, Director of Brand Strategies; Tim Thompson, General Counsel, Paul Thompson, Chairman/President/CEO; Chris Thompson, President-Capital Markets Group; Mark Thompson, Vice-Chairman.

Tongue is firmly in cheek, mind you, when Paul Thompson offers guidance on managing the family dynamic in a family-owned business: “Either come from a family of one,” he says dryly, “or come from a very large family.”

He’s chairman, president and CEO at Country Club Bank, a rare breed in larger area banks, given its family ownership. Large family ownership. And he’s one of five Thompson siblings in leadership roles at the bank, along with Mark (vice chairman), Tim (general counsel), Chris (vice president in the Capital Markets Group), and sister Mary O’Connor (director of brand strategies).

They learned what makes banks work from a Kansas City legend, the late Byron Thompson, who with their mother also taught them a great deal about what makes families work. “When you grow up

in large family,” Paul says, “you learn quickly how to get along. You develop a sense of what each of your own God-given gifts and

talents are—as well as your own weaknesses.”

Then, you divide and conquer by applying everyone’s strengths to the correct challenges. None of that happens, though, without an honest discussion of strengths and weaknesses, and therein lies the challenge for many family businesses: Getting to honest.

“That’s really important,” Paul says, “and I give kudos to my Mom and Dad, but maybe my Mom more, to build that foundation of love and respect for one another.” So how do you get to that? “It’s like they say about planning to be a millionaire: First, get a million dollars,” Paul says. “How did they make it happen? I don’t know, but Mom and Dad did it.”

Before the transition to a second generation, Paul recalls, he attended a bank-management meeting with his father in the 1990s. A speaker was likening business succession to a relay race, something Paul knew a great deal about as a former relay runner. The key, they heard, was the hand-off. “But what I later told my Dad was, that hand-off has to take place in the right zone, or you’re disqualified. Too early, you’re DQ’d, too late, the same. It has to be done at the right time.”

Well, it seems the family absolutely nailed the hand-off from Dad. He bought the former Country Club Bank in 1985, when it had $40 million in assets. Now, three years after his death, it has $1.42 billion, thanks in large part to the work of his children.

“We’re only five of the 385 employees,” Paul says, passing credit to the entire team, which has bought into family themes of being respectful of one another. “But the first word in a family business is ‘family.’ I’d submit to you that in those businesses that are successful, the focus is on that first word. You have to be committed to the family if you want to be successful.”

At CCB, that commitment includes a weekly meeting of the siblings for about 90 minutes to discuss organizational issues, and occasional all-in family retreats, like last year’s trip to Florida to explore longer-term issues like planning for succession. No third-generation members are in the business—yet—but Thompson says the door will be open if and when any of Byron’s 47 grandchildren are interested.

Few parents of 11 must endure the loss of two children the way Byron and his wife did with the highly publicized deaths of Amy and Tricia in the late 1980s, but the strength they drew on from God, Paul says, has proven inspirational. He reflects on their challenges through the eyes of a parent now as old as they were at the time. For the surviving children, he says, those ordeals “affirmed the mortar between the bricks. It takes what you have, and just sets it that much more.”

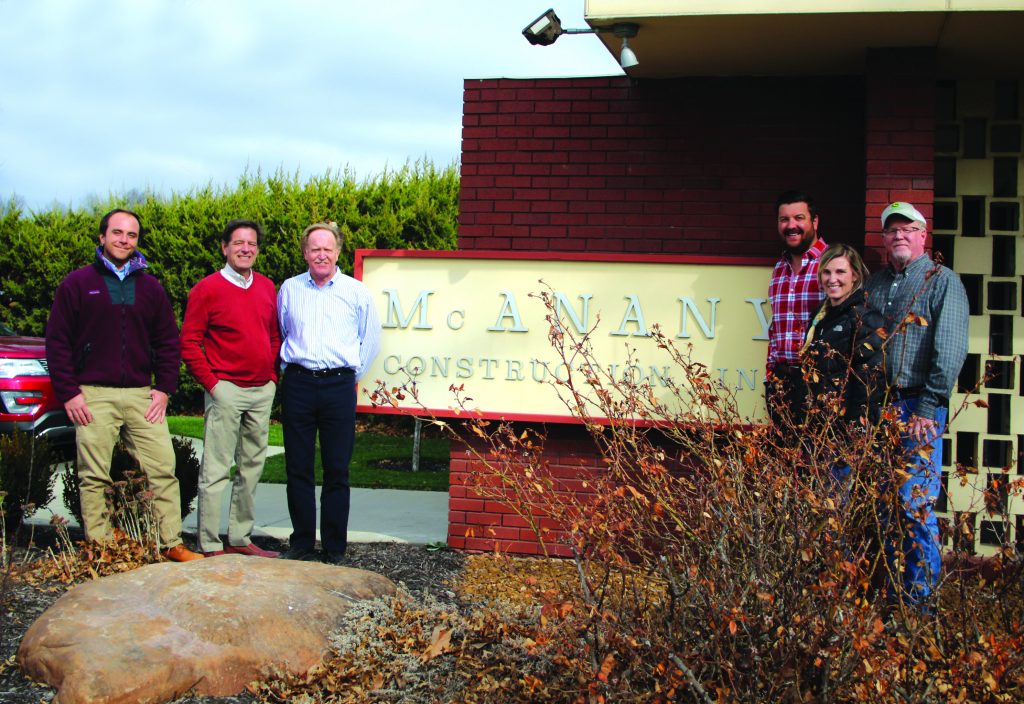

(l-r) Elliott McAnany, Project Superintendent; Pat McAnany, Shareholder; Phil McAnany, Executive Treasurer; Eric Vossman, President; Megan Nowicki, Accounts Payable; Tim McAnany, Executive Secretary. Not pictured: Ben McAnany, Vice President.

Most everyone in business knows the apocryphal description of family-owned companies: Generation One est- ablishes, Generation Two expands, and Generation Three eviscerates. Eric Vossman understands some of the reasons for that. “When you get to the third generation,” he says, “you’re dealing with cousins working together; it’s not brothers and sisters who grew up in the same house and are more likely to look at things the same way.” The 34-year-old president of McAnany Construction is himself a Gen3 leader and shareholder at the company his grandfather founded in 1954. The company specializes in asphalt paving for municipalities and some big-time private-sector clients like Ford Motor Co., BNSF Railroad and General Motors), site development in commercial settings, and even athletic-field development. The latter skill set, no doubt, was responsible for the putting green that graces the front lawn of the company’s offices in Shawnee. With seven family members on staff, roughly 35-40 regular employees and as many as 90 working on projects during peak season, Vossman and his uncle, Pat McAnany, attribute long-term success to some simple factors: Integrity with customers. A rock-solid work ethic among employees. And a shared sense of family that runs past blood-lines. “Some of it goes back to our Christian values,” McAnany says, “and that starts with paying a living wage.” Employees earn union wages, for example, and receive paid health care; in return, there’s a loyalty factor at the company that leads to long-term staffing stability, retained knowledge and more efficient operations. Ownership is shared, but it is also earned, they say, and there is a collaborative culture that drives strategic decision-making. But there’s no denying, McAnany says, that “hard decisions are even harder when family is involved.” Deciding that Vossman would succeed his father, Roger, as president, wasn’t one of those. The company leadership recruited him back from Denver in 2010, where he’d found work at an architectural firm hard to come by during the depths of the Great Recession’s construction downturn. The Rockhurst High graduate, whose uncle sits on that school’s board, came home, spent a few years grooming for the top leadership position, and assumed it early last year. He’s the face of leadership at a company that, in a cyclical sector like construction, is even more cyclical—often reliant on general contractors, who have staff and subcontractors able to work in some tougher conditions, McAnany’s crews can only lay asphalt and concrete under certain weather conditions. That’s why, Pat McAnany says, a long-term strategy is essential. “In this line,” he says, “you can figure that over the course of a decade, you’re going to have three really good years, three or four so-so years, and three really tough ones. If you’re not prepared to handle the tough ones when they arrive, you’re not going to survive.”

Left: (l-r) Grant Renne III, Owner; Linda Renne-Fairchild; Angela Renne, Office Manager; and Ross Renne, Vice President, under a portrait of Grant Renne, Sr., who established a national reputation for heavy moving and foundation repair at the company his father founded in 1873.

It’s hard to put a finger on business success factors that have played out across five generations and 145 years, but Grant Renne III thinks a little bit of luck might just be a part of it. Example: If your thing is foundation repair, you’re more likely to succeed in a market with lots of shifting clay soil than you might be in a metro area sitting on bedrock. In that sense, you’re lucky that your great-grandfather started the business in Kansas City than, say, the front range of the Rocky Mountains. Far more than luck, though, is what a successful company does to leverage the little breaks that go its way: establishing a reputation for treating clients fairly and respectfully, doing what it says it will do, and putting customer satisfaction at the core of all that. Grant Renne & Sons is a specialist in foundation repair and construction, with about 80 percent of its work on the residential side. But it has been involved in some large-scale projects, too, including pouring the piers at Truman Sports Complex when Grant Renne Jr. was running the show in the early 1970s. Renne’s great-grandfather, George Renne, laid the foundation for today’s organization back in 1873, when the work often entailed moving entire buildings to new foundations, using horsepower that ran on oats, not diesel fuel. Today, it’s a company in transition, as Grant III’s son, Ross, representing the fifth generation, prepares for eventual leadership, working with his wife, Angela, a native Cypriot whose life intersected with Ross’ when he was studying economics at the University of Kansas. Still closely tied to the company is Grant III’s sister, Linda Renne-Fairchild, the longtime office manager. The business structure today reflects lessons that Renne’s father learned the hard way decades ago, when differences of opinion with his brother led to an eventual buyout. “I think what Dad learned from that is that single-ownership was the way to go,” Fairchild says, and that model has worked for all involved ever since. If there is to be a Generation Six, Ross says, it will be the result of having embraced two fundamentals of long-term success: “Customer satisfaction, and watching your debt.” Customer satisfaction, his father says, is often a function of integrity, and looking at each job as if it were his own foundation—and finance—in question. “Sometimes it means telling people they don’t have a problem,” Renne says. He tells the story of an older woman who asked him for a second opinion on a foundation quote given by a competitor. The other company said the work would set her back $20,000. “But that basement was in better shape than mine,” Renne says. “I told her to go upstairs, take that $20,000 and plan a great vacation with her grandkids.” Some shadier elements in the business, he said, may look at an older homeowner as a prime target. “But that old grandmother may have a pretty sharp lawyer son, who she‘ll run things by,” he said. That kind of thing eventually will catch up to you, so being underhanded simply doesn’t pay in the long run, Renne says. “Just do the right thing,” he says, “and maybe your business will exist for 145 years.”

Front row (l-r) Sheila Meyer; former office manager; Amanda Meyer, communications manager; Chelsea Ireland, payroll manager. Back row: Russ Meyer, founder/CEO; John Meyer, sales executive; Rusty Meyer, President.

The timeline at Meyer Laboratory has at least two critical inflection points: The first was with its founding 40 years ago, when Russ Meyer decided that the up-and-down compensation available to a computer salesman afforded little long-term upside. The second was when his son, Rusty, joined the company 13 years ago. Until that happened, a family-business structure wasn’t part of the plan. “I can’t tell you anything profound about it,” Meyer says, looking back. “It started with the goal of being able to support my family.” His dive into entrepreneurship, he decided, would focus on something repeatable and sustainable. “Something that, if people bought and liked, I hoped they would continue to buy, and that led me to institutional cleaning supplies.” He made that move before Rusty, who’s president of the company today, was even born. For the first nine years of the business, Meyer would buy supplies direct from a manufacturer, re-label, then sell under the Meyer Laboratory brand. Nearly a decade after startup, the company took its first tentative steps into production. Along the way, the passion that both father and son had for baseball was being nurtured. Rusty won a state championship with Blue Springs High School, earned a scholarship to Texas A&M as a catcher. He was a 13th-round draft choice of the Royals, whose stadium is just a few miles west of the Meyer Laboratory plant along Interstate 70. But injury derailed Rusty’s dreams of playing pro ball. He signed on with the company, which was already expanding as a family concern: Meyer’s wife, Sheila, was working as office manager, and her daughter, Chelsea Ireland, started with an office-support role. Rusty’s entryway was sales, and to his surprise, he was good at it. He set sales production records for the company, and started grooming for the transition of leadership. Today, he and his father share ownership of Meyer Laboratory, which also has his cousin, John Meyer, on the sales staff, and Rusty’s wife, Amanda, handling on-line, communications and marketing functions. Since Rusty began day-to-day administration, he says, the company has experienced at least five-fold growth. It now employs more than 50 people at the 120,000-square-foot headquarters and production facility, and about as many in satellite sales and production operations. Among those employees, Rusty notes, are about half a dozen father-son or father-son-in-law duos who add an additional family dimension to this family business. “We’re always looking for good people,” says Russ, “and when you’re a small organization, you spend a lot of time with employees and get to know them, so when they have kids who are at the point of starting careers, it can be a natural fit.” Working together has added a new depth to the father-son relationship, something that goes beyond simple business building. “I enjoy the chess match with my Dad, and it’s fun to be able to work together with other members of your family,” Rusty says. “Rusty was going to be pro baseball player, then he got hurt,” his father says. “That was his goal all along, and my goal for him. Until then, I really didn’t think about him coming in the business. But it’s great now that it’s happened.”