HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

We’ve heard it time and time again from executives who are re-assigned to locations in Missouri from parts east and west: “I never knew things were so good here.” They’re talking about the quality of life here. About the affordability. About the competency of the work force. About the ability to get from here to almost anywhere else in the continental U.S. in about as much time as it takes to watch an NFL game. There are a lot of reasons. But nearly every one of them can be tracked back to a common source, and that is good, old-fashioned Missouri values. Things like hard work, self-reliance, character, integ-rity, commitment, sacrifice, determination—all of them, to some degree, helped build this state. And all of them are represented across the breadth of this years’ 50 Missour-ians You Should Know.From the leaders of business conglomerates to small-town entrepreneurs, from health-care professionals to lawyers and clergymen and women, from farmers and ranchers to the makers of Very Big Things, this year’s 50 Missourians, like the 350 who preceded them since 2011, reflect the very best of what makes the Show-Me State so . . . well, Showable. If you want to know what sets Missouri apart, get to know these giants of business and every-day citizens. And consider yourself Shown.

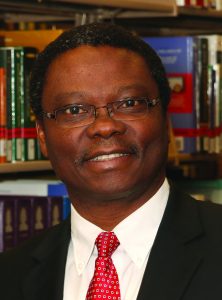

Samuel Achelifu

Samuel Achelifu

Washington University, St Louis

After surviving a long-running civil war, Samuel Achelifu was one of five Nigerian students who received a French government scholarship to attend graduate school there. His path to St. Louis and the research war on cancer started at the University of Nancy, then to Oxford in England, before a mentor recruited him to America at Mallinkrodt Medical. “I wish I could say being here was deliberate,” says Achelifu, now chief of the optical radiology lab at Washington University’s Siteman Cancer Center. “I found St. Louis so very welcoming, and it created opportunities for what I wanted to achieve in life.” Those achievements benefit patients in various ways, most recently with his role in inventing goggles that allow surgeons, using light, to see hard-to-find cancer cells in the body. Whether it’s cancer or Alzheimer’s, Achelifu says he takes a patient-first view. “Most of the time, researchers are chasing the problem, as opposed to the cause,” he says. “The key question I want to know with cancer is what causes gene instability in the first place. … My dream is to dissect the causes of diseases we face today.”

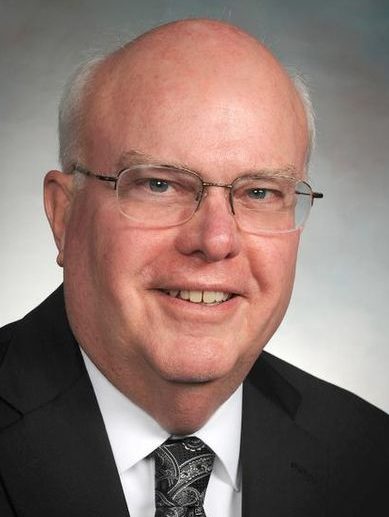

Jim Anderson

Jim Anderson

Cox Health, Springfield

For more than a quarter-century, Jim Anderson was the face of Springfield business as president of the Chamber of Commerce. He won multiple awards by forging a more cohesive economic development strategy to encourage business expansion or relocation there. He left that role in 2014 to sign on with Cox Health, which operates the 658-bed medical center that serves as a health-care anchor for southern Missouri and beyond, as vice president of vice president of marketing and public affairs, then took on duties for community and public affairs last summer. A native of the area, he started off in education as a speech instructor before taking on a school-community relations role that steered him in a new direction. After nine years as president of the Jefferson City chamber, he headed back home. Not long before he left the chamber, it was named National Chamber of the Year in 2012 by the American Chamber of Commerce. Anderson said then that his approach to relationships was grounded in a couple of constants: “I never tried to draw a line in the sand,” he said, and “I always try to look for the best in everything.”

Rob Barrett

Rob Barrett

Heritage State Bank, Nevada

When Rob Barrett became chairman of the Missouri Bankers Association last year, he completed one-half of a historic first—his wife, Susan, held the same role in 2010, making them the first husband-and-wife team ever to lead a state association nationwide. Banking in the Barrett family, then, offers a rare perspective on the health of community banks in the Show-Me State. Their overall vitality, he says, “is strong. It will be challenge for a variety of banks to offer the products we have to offer now, from a tech standpoint,” he says. “It’s expensive if you don’t spread that cost over a lot of customers.” Mound City was home for Barrett, whose youth was divided between Holt, Atchison and Nodaway counties. He earned a master’s in education after picking up a degree in agriculture at MU, “but I wanted to be in business, then got the job I was looking for” after a conversation with his own banker. In Nevada, he found something of a sweet spot: “We have the quality education, and a real quality lifestyle, literally 100 miles away north or south from shopping, entertainment or dining,” he says.

Sherrill Bass

Sherrill Bass

Cable Dahmer Cadillac, Kansas City

Sherrill Bass grew up well aware of the Miracle Mile—the strip of Noland Road packed with auto dealerships in her native Independence. But before becoming a part of it as director of customer experience for one of the region’s largest dealers, she took a different route. “We didn’t move much when I was young, but because of school-district boundary changes, I went to four grade schools, three junior highs and one high school” she recalls. Result? “It made it easy to communicate, and meeting people was easy.” She parleyed that skill into 33-year banking career, mixing in values learned at home. “My parents taught me at an early age the value of a dollar,” Bass says, “and about treating people fairly.” Those were great fits on the way up from drive-in bank teller to vice president at Enterprise Bank. “I absolutely fell in love with banking; I had a passion for it,” she says. She was both business banker and personal banker for Carlos Ledezma, who was moving his way up at Cable-Dahmer before acquiring it. And after a long recruitment, Bass traded deal-making platforms, and again, she‘s found her passion.

Scott Blank

Scott Blank

Bistate Oil Co., Cape Girardeau

There’s simply no way to hide from market forces, even in far southeast Missouri. For Scott Blank’s small chain of convenience stores, that means adapt or die. At Bistate Oil Co., he said, “we changed our model around about five years ago to focus in on food, because of declining margins in tobacco and alcohol—those were two big staples—and with declining demand for fuel.” Something had to replace those, says Bistate’s third-generation owner, “and I believe strongly in food. If you’re not in it and you don’t change your model in the next 10 years, I don’t know if you’re going to be in this business.” In that sense, the company founded by his grandparents as a gas station/diner combo is coming not quite full circle as part of what he calls a revolution in that sector. He’s fortunate then, to be in a climate that he believes is vested in the success of small business, with an active chamber of commerce, plus an economic anchor for the region, Southeast Missouri State University. “That’s a big asset, having access to not only that applicant pool,” Blank says, “but the professors are extremely open to meeting with small business.”

Cindy Brinkley

Cindy Brinkley

Centene, St. Louis

In passing and in jest—Cindy Brinkley observes “I’m the Forrest Gump of business.” There is some truth to it. A small-town girl from Milan in north-central Missouri, she has staked out leadership roles with companies or in sectors wracked by transition—Southwestern Bell as it morphed into AT&T, General Motors post-bankruptcy, and, since 2014 with Centene, in health insurance, where she was named president and COO last fall. That path, she says, started with values. “I was very much influenced by that lifestyle and home life” as one of six children raised by parents who ran companies—in her dad’s case, a farm-implement company; in her mom’s, a nursing home. Her repuation for understanding organizational cultures resonated with Centene CEO Michael Neidorff, an acquaintance who recruited her in 2014, and she made the move into health insurance. By providing health care for under- and uninsured consumers, now including those the Kansas City market, she beams, “we were just recognized by Fortune as No. 17 of companies that are doing well by doing good.”

![]()

Greg Brown

Greg Brown

Learfield, Jefferson City

If Greg Brown represents anything, it’s that Learfield Communications can be somewhat flexible in the application of career discipline: While he’s president and CEO of the communications giant today, he was once personally fired by Clyde Lear, the founder of the company. And rehired. On the same day. Brown argued that if he couldn’t succeed as a manager, perhaps he could be more effective in sales. Turns out, he had management chops after all, succeeding Lear in the head office. A native of Leon, Iowa, Brown earned his degree at Truman State, where he did a stint as an intern for John Ashcroft, Missouri’s attorney general at the time. Under his executive watch since 2009, the company has grown form a small regional network into a diverse media enterprise, big enough to command north of $1.2 billion in 2016, when an East Coast investment group acquired it. Learfield is now a marquis broadcaster for college sports, and for his work in the field, Brown last year was named by SportsBusiness Journal as one of “The 50 Most Influential People in Sports.”

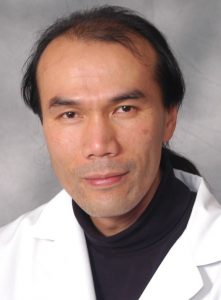

Paul Chan

Paul Chan

Saint Luke’s , Kansas City

Health care, medical research and the economic and social status of patients are not separate issues for Paul Chan—they are inextricably connected, and he hopes his work will apply to all. Born in Hong Kong and raised on New York’s lower east side, he knew what it meant to lack means. Through a spiritual and intellectual journey, he found solace volunteering as a teacher in Appalachia before earning his medical degree, and treating residents of a Navajo reservation afterward. Even today, he says, the work he’s done there and in cardiology research “seems like two parallel universes. But it gets back to why I chose medicine to begin with.” It was on a mission to Nicaragua that the deeply spiritual Chan saw faith-based workers treating patients, “and it was the a first-time realization that they didn’t need to be separate parts of my life.” With the concept of service central to what he does, he pursues solutions to intractable problems. “We know about health disparities linked to race and income, he says, “but our greatest challenge is, what are we going to do about it? How can we narrow those disparities?”

Bob Chapman

Bob Chapman

Barry-Wehmiller, St. Louis

What does it take to earn a reputation as one of the world’s best CEOs? For Bob Chapman of Barry-Wehmiller, it starts with a commitment to applying his role as chairman and chief executive of a $2.5 billion global company in ways that differ sharply from those focused on bottom lines and short-term shareholder returns. Inc. magazine ranked him No.3 among top executives worldwide in large part because of his unique view on what it means to lead a business. Chapman has long advocated abandoning traditional management practices for what he calls Truly Human Leadership—making employees feel not just valued, but as if they’re an integral part of the company’s purpose. The global company today has 12 business units and clients in the packaging, paper converting, sheeting and corrugating industries. “I get a lot of satisfaction from helping people see that there is a greater purpose in life than simply making money, raising a family and having fun,” he blogs. “Immense personal fulfillment and joy can be found by choosing a path that contributes to the betterment of our world.”

Chris Chinn

Chris Chinn

Ag Department, Jefferson City

Five generations of family farming will leave an imprint: For Chris Chinn, it’s a value set framed by a resolute work ethic, integrity, courage, fiscal responsibility, consistent communication. She unpacks those tools every day as the state’s top ag official, overseeing policy for a sector with nearly $18 billion in sales and far more in added-value impact, and looking for ways to expand that economic base. Leaving the farm wasn’t easy when Gov. Eric Greitens summoned her last year—but in some ways, she hasn’t left it. The family farm, she says, “is not only a business but it’s also my way of life.” Stepping back from day-to-day duties has not meant abandoning them. “My conversations with my husband revolve around our kids and our farm. It’s our life,” she says. “We talk about his day and what’s going on at the farm—challenges, opportunities and everything else that goes into a business. We decide as a team how to move forward.” She also continues to write the checks. “I think it’s essential to be in tune with farmers and ranchers,” Chinn says, “and what better way do that than to be the one sitting at the desk paying the bills each week?”

Angela Clabon

Angela Clabon

Davis Health Center, St. Louis

Over the course of more than 30 years, Angela Clabon has been on the front lines of the nation’s battle with the costs of health care—and she knows that the true casualties are the under-insured and the uninsured, a group that includes the homeless as a particular health-care challenge. “Primarily an economic problem, homelessness is also a social problem,” she believes. “It’s an issue that has been extremely stigmatized by our nation’s culture and society, which often leaves homeless individuals overlooked by those with the capabilities and resources to help.” As the most vulnerable members of society, she says, they are usually the last to reach out for help. One pathway for that help comes from her work at the Myrtle Hilliard Davis Comprehensive Health Centers, which treat nearly 30,000 patients a year and serve as training facilities for health-care professionals who will go on to careers as X-ray technicians, health educators, or careers in dentistry, pharmacy and laboratory work. Clabon, a St. Louis native, signed on as chief financial officer there in 2005 and became CEO in 2014.

Diane Compardo

Diane Compardo

Moneta Group, St. Louis

For many an aspiring chef, the romanticism of cooking loses some luster when confronted by actual restaurant work. Thus it was with Diane Compardo, and a great many high net worth investors can be thankful for that. An Illinois farm girl raised with five siblings, she learned the work ethic that defines her performance today. At Southern Illinois University, she picked up an undergrad and master’s degree in accounting, with a concentration in taxation, then went to work for what is now PwC in St. Louis, providing senior executives and their families with comprehensive financial planning services for many of the largest companies in town. And she did it well: She was the only adviser from Missouri to make the Financial Times’ inaugural Top 100 Women Advisers list in 2014, and has been similarly recognized by Forbes and Barron’s. “I am humbled by the industry recognition,” she says. “Perhaps that’s due to the fact that I embrace my farm-girl roots and strive to stay true to who I am as a person. I was taught that if you work hard, treat people with respect, and never forget where you came from, success will find you—however you define it.”

Joel Denney

Joel Denney

National Guard Assn., Columbia

“When we look back on our lives,” says Joel Denney, “it should be obvious that we’ve left more than we have taken.” The means for him to achieve that goal has been education, and his track record cuts a broad swath across all aspects of it in the Show-Me State. He followed up his degree in political science and history at MU with a master’s in education and general school administration from Missouri State, the went back to Mizzou for his Ph.D. in general education and education management. He served in K-12 teaching and administrative roles, and was second-in-command at the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education—the first person in the history of the state to be appointed to the position from outside the agency. Then came nearly 11 years as associate executive director for the Missouri School Boards Association before the Guard came calling in 2011. “Instilled in me by my mother at an early age was that we ought all be motivated to “be givers while on this earth and not takers,” Denney says. “That simple goal has been a driver for me—a goal I learned at my mother’s knee.”

Jimmie Edwards

Jimmie Edwards

Public Safety Department, St. Louis

“Having grown up in the shadow of St. Louis’ most notorious housing project,” says Jimmie Edwards, “I well understood that had it not been for a few lucky breaks—and the support and guidance of my mother, other family members and dedicated teachers—my life could have gone in an entirely different direction.” After earning a law degree from St. Louis University, he became a circuit court judge in 1992, serving as administrative judge of the family court and chief juvenile court judge for more than five years, and founding an academy to turn around at-risk youth. More recently, he’s been called to help thousands of others who have grown up the way he did find their own lucky breaks, as the city’s director of public safety. “At its best, government and the courts dispense justice and hold the guilty accountable,” he says. “But good governance also seeks out the root causes for societal dysfunction, shows compassion when warranted and works to improve opportunities for future generations. … I still believe that committed community partners will help me change the behaviors and outlook of citizens and neighborhoods alike.”

John Fischer

John Fischer

Olin Corp., Clayton

When John Fischer signed on for a second stint with Olin Corp. back in 2004, he resumed an executive journey that in a little more than a decade would lead him to the pinnacle of a key jewel in the crown of St. Louis-area business. Olin Corp., with more than 6,300 around the world, is part of a stable of Fortune 500 companies based in St. Louis, and it’s a major force in the nation’s production of chlorine, caustic soda and ammunition. Its founder, Franklin Olin, was a major donor to Washington University, and the prestigious Olin Business School there was named in his honor in 1988. Fischer moved quickly up the ranks after returning to the company, first as vice president for finance, then adding controller to his title a year later, then to chief financial officer in 2014, where he was involved in the biggest acquisition in the company’s history, the $5 billion acquisition of Dow Chemical’s chlorine business in 2015—a deal that nearly doubled the corporate revenues to $5.5 billion. That year, he was elevated to president and chief operating officer, and in 2016, president and CEO.

Nolan Fogle

Nolan Fogle

Fogle Enterprises, Branson

On the red-hot field of competition that is the restaurant scene in Branson, “subtle” will earn you a sign out front that says “For Lease.” Nolan Fogle has no intention of going that route. Hence the 43-foot chicken that towers over Country Boulevard, beckoning diners to the Great American Steak and Chicken House. Or at Pasghettis Restaurant and Attraction seven blocks away, where a 15-foot meatball is under assault by a 50-foot fork. If you’ve dined in Branson, there’s a good chance you’ve done business with Fogle. Through his Fogle Enterprises, he owns the Great American and five other restaurants in the tourist capital of the Ozarks, including Whippersnappers, the seafood buffet, Fall Creek Steak and Catfish House, the world’s largest Cicis Pizza and Family Fun Center, and Burger Shack. He started his company in 1992, not long after graduating from Plato High School. He’s a one-man tour-de-force in Branson dining, but during the warm-weather months, you’re as likely to find him on a baseball diamond as a restaurant, playing second base for the Nightmare/Miken men’s professional softball team.

June Fowler

June Fowler

BJC HealthCare, St. Louis

Somebody needs to take a head count: Is there really only one June McAllister Fowler? Consider this: She serves on boards dealing with transit and airport issues in St. Louis, on UMB Bank’s local advisory board, on the Public Affairs National Council at Washington University and the Health Care Industry Council for the Federal Reserve Bank there. She’s past chair for the Girl Scout Council of Greater St. Louis and the Metropolitan Association for Philanthropy, she teaches Sunday school classes; she directs the children’s church services. Oh, and she has a day job, too, as senior vice president of communications, marketing and public affairs for BJC Healthcare, a $4.5 billion, 15-hospital network with 31,000 employees and nearly 155,000 patient admissions each year. She got there after a stint at pharmaceutical giant Mallinckrodt, which itself came after 16 years in urban planning for St. Louis County. Fowler has bagged an armful of awards for her contributions to civic, educational and leadership groups and causes, and for non-profit philanthropy and for professional recognition in communications.

Sarah Galbraith

Sarah Galbraith

Missouri Star Quilt Co., Hamilton

Sarah Galbraith became a Missourian at 15, when her father brought the family from sprawling Los Angeles to tiny Hamilton to let them experience farm life. But even from there, she’s got a toe in the pond of global commerce. Ten years ago, faced with the dearth of employment options facing small towns everywhere, she and her brother founded Missouri Star Quilt Co., now boasting the world’s largest selection of pre-cut quilting fabrics. How did they do it? With determination, trial and error, and a computer connection. Lack of a college education, Galbraith says, “never stopped me from learning. I read books and was very interested in business.” Once the business launched, they learned to react—fast. “If it wasn’t working, stop, change and fix it,” she says. “We were able to be very agile when we needed to, and learned very quickly that it is better to admit a mistake rather than fight to be right.” Behind it all was a yearn to teach quilting skills to people anywhere. “Take what you love and share it in a way that can be consumed by a larger audience,” she advises, “Don’t feel stuck in your ‘small town.’ You can do anything and make an impact.”

Lisa Garney

Lisa Garney

LMG Construction, Kansas City

Quick: Name a licensed master plumber who holds a law degree, studied at the London School of Economics, and has been mentored by Condoleeza Rice. If you said Lisa Garney, you’re spot-on. The owner of LMG Construction grew up around plumbing, and learned invaluable lessons from her father, Kansas City’s iconic Charles Garney. Among other things, she says, “my dad taught me the power of entrepreneurship”—including the value of hard work, the importance of a strong business foundation, including a good team, clear objectives, accurate financials and a strong network.” She also learned about margins, crew productivity ratios, time and cost to complete, cash position and saving money. “My mom taught me the importance of community and tirelessly giving back,” she says, and applications of both lessons has made her company a rising star of women-owned business here. “If you can master the fundamentals of running a small business successfully, through both high market and recession periods, you can do anything,” she says. “The fundamentals of running an organization are the same.”

Chris Gregory

Chris Gregory

Heartland Horsehoeing, Lamar

“When your passion is also your living,” Chris Gregory says, “it makes being driven a very good attribute.” So when he was looking for career direction, he practiced hard and worked with anyone who would teach him about becoming a complete farrier. “That takes a lot of early mornings to study and a lot of late nights in front of the anvil,” says Gregory, founder of Heartland Horseshoeing, a highly regarded school for learning the trade. “I also pursued certifications and competitions all over the world that allowed me to test and build my skill.” He spent much of his youth on horseback in his native New Mexico, earned a college rodeo scholarship—yes, they do exist—and “all through college, I shod horses—and had a lot more money than most of my friends as a result,” Gregory says. Missouri is a solid spot to ply that trade, one of the Top 10 for horse ownership. “It is hard to get a good farrier, so a lot of horse owners are not happy with having to deal with finding and keeping a competent shoer,” he says. “This leads a lot of them to recognize the global need for good horse-shoers, and they then look for the best place to learn the trade.”

Robert Hill

Robert Hill

Kauffman Foundation, Kansas City

Early in life, Robert Hill had a pretty good grasp on poverty in America. He was raised in Brownsville, Texas—“We were poor, but didn’t know it,” he says of growing up in the poorest of Texas’ 254 counties. As a Vietnam-era conscientious observer, he did alternative service in LA’s formidable South Central, in the poorest ZIP code in America. “So 16 of my first 21 years were spent in, arguably, relative poverty, although I didn’t suffer from it,” he says, adding dryly: “But it does shape your world view.” Faith exerted a pull, and he went to divinity school at Vanderbilt, later making his way to Kansas City, where he served for more than 30 years as minister at Community Christian Church. Retirement has not slowed his interest in social issues, and he’s now a consultant with the Kauffman Foundation, focusing on community engagement with public education. He also is a consultant with What U Can Do, which promotes citizenship engagement, and co-founded the Metro Organization for Racial and Economic Equity, among other efforts. He has done a lot, but “we still have work to do,” he says.

James Holloran

James Holloran

Holloran, Schwartz & Gaertner, St. Louis

A local publication once described St. Louis lawyer James Holloran as “a Democratic rainmaker and the man whose ring you kiss if you want to ever be a circuit judge in this town.” But never let it be said that the serious nature of Holloran’s work—in big-city politics, or with the highly regarded collection of trial lawyers at his law firm—occludes his appreciation for good friends, good times and good music. Forty years ago, he founded a one-room pub to recognize his Irish heritage, and today, McGurk’s is a St. Louis institution known for its authentic Irish music, food and libations. Of course, the law part made the pub part possible, and that all started when this hometown icon earned an engineering degree, then a law degree, both from St. Louis University. He has taken more than 200 cases to jury verdict in state and federal courts, focusing on cases of medical negligence, vehicle accidents and product liability. And he’s a member of the Inner Circle of Advocates, an organization with no more than 100 members nationwide who have met strict criteria for achievements as trial lawyers.

David Hotz

David Hotz

Dock Realty, Lake Ozark

For the record, Dave Hotz did not attend a one-room schoolhouse in northwestern Iowa. It had two rooms. But it prepared him to head to Iowa State, and a degree in computer engineering—“I have always been a problem-solver,” he says. Hotz became a property owner on the Lake of the Ozarks by virtue of a Minnesota winter that featured ice-fishing huts parked outside the Hotz lake home for six months. Friends with a condo on the lake in Missouri suggested they take a look. “The scenery was beautiful, home values were attractive, and the season was three months longer,” he says. Love at first dip. Regrettably, he says, he didn’t buy the dock at that site, and immediately discerned a need for “a concierge-based company that would oversee and assist in the process purchasing a boat dock and having it moved and installed.” Thus was born Dock Realty, serving a market with 35,000 residential docks and average home ownership of around five years. He also is still tinkering, helping bring to market Dock Lifeguard, a device that warns swimmers and boaters of hazardous electricity in the water.

Kavita Katti

Kavita Katti

University of Missouri, Columbia

Concepts of hard work, truthfulness and dignity came easily to Kavita Katti, for good reason: Her father was among Mahatma Gandhi’s peaceful revolutionaries who earned India’s independence from Britain. “Above all,” she says, her parents instilled in her the obligation to “make a true difference in the lives of people.” That started with education back in the village of Satti, then teaching in a small town, on through a career that has brought her to MU as a researcher in chemistry, radiology and academic research. “I was always interested in science right from my childhood,” she says. “I always wanted to be a medical doctor; the closest to my dream has indeed come true through my current job, where I have been working for over 25 years in radiology.” To that task, she brings a truly global perspective. “From my childhood background, I know how difficult it was then and still true today that people across the world need better medicines, medicines that treat diseases with minimal side effects, and medicines that are affordable to rural populations,” she says. “This urge to contribute to humanity drove me to take up a career in health-related sciences.”

Samuel Knox

Samuel Knox

Unite Publication, Springfield

Its status as Missouri’s third-largest metro area belies one incontrovertible fact: Springfield does not look like the rest of the Show-Me State. While the black population of the state is 11.8 percent, African Americans account for less than 5 percent of Springfield’s population. It’s an even greater disparity compared to the 49 percent black population of St. Louis, or the 29 percent in Kansas City. For nearly 30 years, Samuel Knox has been devoted to attacking some of the consequent economic conditions grounded in those numbers. In 1988, he co-founded Unite Publication, focusing on information that African American and multi-racial families could use to better their lives in southwest Missouri, and he’s managing editor for that venture. Its goal was to explore local, regional and national issues by offering inspirational stories that empowered and connected readers. More recently, he’s aligned in a mentoring role with the eFactory at Missouri State University, a tech-focused entrepreneurship center that promotes start-up success for minority business owners.

Ken Kranzberg

Ken Kranzberg

Arts Foundation, St. Louis

“Why would I be crazy enough to go out on my own?” Ken Kranzberg thought at the start of his career, so he signed on with the company owned first by his grandfather, then his father. A year in, he wasn’t entirely sure that packaging-material sales would be his thing. “After the first shaky year, I thought do something else and leave, but decided to give it another year.” A smart choice personally, but maybe an even better one for St. Louis. The chairman of TricorBraun has emerged as half of one of the most philanthropic couples in town, and hundreds of non-profits have benefitted from personal donations and contributions from the Kranzberg Arts Foundation. “We always gave—never a lot of money at once, but my grandfather always said he never knew man who went broke from giving,” he says. He and his wife have donated primarily to Jewish causes and the restoration of buildings in the city’s Grand Center area. Arts, in particular, resonate because, he says, “a culturally significant community can attract people to live and work there, and to tour. That’s been a real effort on our part.”

Andy Kuntz

Andy Kuntz

Andy’s Frozen Custard, Springfield

The modern-day adage that tells us most American workers can expect to have a dozen employers and three or four career tracks? It falls on deaf ears with Andy Kuntz. Although it might not be entirely accurate, it’s entirely fair to suggest that he has been in business since he was a kid. He started at a small frozen custard shop while he was still in high school, and 32 years later, he’s still there. Owns it, in fact. He had inside connections from the get-go: His parents, John and Carol Kuntz, put the first store in Osage Beach in 1986, then moved to Springfield, beginning the long, arduous trek to overnight success. Young Andy learned every facet of the business, before eventually assuming ownership after his father’s death in 2008. Today, Andy’s proclaims itself the world’s largest dessert-only chain—don’t go there looking for a burger—and it operates more than 50 stores from Arizona to Tennessee. The chain is still run by the philosophy set down by Kuntz’s parents: “If you are in the service business, you have to hire people that have a strong desire to serve. Pay them above average, train them well, and demand nothing but the best.”

Doug Lilba

Doug Lilba

Missouri Senate, Poplar Bluff

Doug Lilba still remembers June 9, 1971, a Wednesday, when a young entrepreneur from Greenville, 35 miles up U.S. 67, celebrated his first day as owner of Doug’s Sinclair & Tire. There, his first business venture entailed pumping gas, fixing flats and washing vehicles, drawing on the work ethic and determination he learned growing up. It would not be his last. A trend-bucker at birth—his hometown’s population had been cut in half in the decade before he was added to it—Libla went on to create various companies in partnership with his brother, Dave. Their companies have operated in manufacturing, trucking, telecommunications, heavy construction, automotive products, industrial supplies, and commercial and industrial real estate venues. In 2012, he retired, but decided there was still work to be done—in the General Assembly. He won the 25th District Senate seat, hoping “to use my business experience to make the state a better place for student education and provide more opportunities for our young people and families,” he says. “Hard and smart work is the cornerstone of realizing your dreams.”

Gregg Lombardi

Gregg Lombardi

Neighborhood Legal Services, Kansas City

Gregg Lombardi isn’t just a lawyer—he played one on the Big Screen. In 1990, when Mr. and Mrs. Bridge was filmed in Kansas City, he landed a bit part with the opposing counsel team across the courtroom from Paul Newman’s character for about $27 a day. “I think Paul got more,” he cracks. Ba-dum-bump. A Kansas City native—his great-grandfather ran for mayor against the Pendergast machine—Lombardi was the longtime executive director of Legal Aid of Western Missouri. He started Neighborhood Legal Services, with the same goal of providing affordable counsel. “The legal system is going through a major crisis, not just in KC, but nationally,” he says. “If you’ve been wronged (other than a personal injury) and your damages are under $50,000, your odds of finding an attorney to represent you cost effectively are close to nil.” A former big-firm lawyer, he found that “my heart is in working on social change.” By changing career focus, he helped build what was then the largest medical-legal partnership network in the country and gave hundreds of disabled Missourians access to medical care.

Vicki McCarrell

Vicki McCarrell

Moebius Foundation, Pilot Grove

Vicki McCarrell transplanted her central Missouri roots and education training in 1974, going on to become president of a fashion school in Los Angeles. But a few years after parenting duties were added to the mix, it was time to re-root. “When Sean was ready to start kindergarten, I wanted him to go to the same kind of K-12 school, so the kids would know him,” McCarrell says. “I didn’t want changing schools like he would have to do in L.A.” Something else about her son was starting to re-order her life: A rare neurological disorder called Moebius Syndrome, a lack of facial nerves that makes smiling and frowning impossible. She could find only one other parent in L.A. with a child so-affected, and there was no support group. So she took action to establish the Moebius Syndrome Foundation, where she’s been president of the board since its inception, handling the finances and working with the National Institutes of Health to fund research. That her work can unfold far from urban centers, she says, is one benefit of modern life, which allows the quality of life she wants and the work that satisfies her.

Mary McCleary Posner

Mary McCleary Posner

Salute to Veterans, Columbia

During a 25-year stint in New York, Mary McCleary Posner would occasionally hear the same refrain from her father: “He told me that I was able to enjoy the corporate career that I had because very brave men and women had risked their lives to give me the freedom to do so,’ and if I could ever figure out a way to say ‘Thank You,’ I should do it,” she remembers. When she came back to Columbia three decades ago, she did, starting with a parade. Thus was born the Memorial Day Weekend Salute to Veterans, which celebrates its 30th show this year and stands as one of the largest free events of its kind nationwide, drawing 50,000 people and marshaling 2,000 volunteers. The first year, a flyover salute to fallen comrades featured a B-25 with smoke trailing from one wing as it sailed over the Capitol dome. “It was a moment I will never forget,” Posner says. But then, “one little old lady did call the police and told them we had shot down an airplane.” The show not only recognizes veterans and their sacrifices, but promotes a better understanding of Memorial Day, and helps raise funds to build permanent public memorials.

Todd McCubbin

Todd McCubbin

MU Alumni Association, Columbia

Now this is a diplomat at work: Asked about his favorite food or beverage while tailgating at the University of Missouri, Todd McCubbin eludes the tackle. “I have the good fortune of visiting many alumni tailgate parties on game days,” he says. “The food is always great, the company is always better.” Well-played, sir. That’s part of his charge as executive director of the MU Alumni Association, where he manages 45,000 members, along with the Mizzou Annual Fund. Cut him twice, and he’ll bleed two colors: Black and Gold. He became an alumni relations coordinator in 1995 and climbed the organizational ladder to his current post in 2004. There, his attention is divided between legislative advocacy, athletic events, chapter relations, marketing, annual giving and non-dues revenue programs. After Truman State (journalism and communications), he picked up a master’s in education in Columbia. What sets MU apart for him? “Diversity and traditions,” he says. “As a kid from a small town (Harrisburg, Mo.), Mizzou afforded me a chance to meet people from many backgrounds and cultures.”

Bruce Mershon

Bruce Mershon

Mershon Cattle, Lee’s Summit

Family and tradition are fundamentals of agriculture, but these days, so are innovation and technology. Bruce Mershon lives all four aspects with the work done at Mershon Cattle and Mershon Farms, based in Lee’s Summit. The operations span 2,000 acres of land, including productive farmland that remains in largely urbanized Jackson County, and a 12-county area of western Missouri. with up to 3,500 head of cattle on ranchland and feedlots. Mershon is also at the tip of the spear in research efforts to make cattle production more efficient and improve breeding conception rates, working with the University of Missouri. Those modern-day efforts are grounded in family farming lore that dates to the 1860s. “My folks still live on the home place where Dad grew up,” he says, in the house his grandfather built in 1915. He and his siblings bought the operations from other members of the family more than 20 years ago, and he knows that passing along a legacy to his own children and nephew imposes an obligation. “Our focus is to be more productive and better stewards of the land every day—that’s what we really want to strive for.”

Keith Miller

Keith Miller

Columbia Associates, Columbia

Maybe it’s the depth of his design skill that makes Keith Miller such an in-demand commodity in Columbia Associates Architecture. As principal architect for the firm he and his wife, Kathy, founded in 2001, Miller is a go-to guy for civic projects in various disciplines. Committtee roles? You bet: For athletic improvements at Rockbridge High School in town, for the city’s youth soccer infrastructure, for a new regional Catholic high school, and for a city panel on facility improvements serving low-income residents. He also has logged seven years as vice president of the Columbia Art League. CCA is a multi-faceted firm capable of working on structures ranging from churches schools and health-care spaces to residential, office and commercial space, hospitality venues—even parks and public spaces. Miller has been recognized for his achievements in master planning for vacation properties in the Midwest. One key to success is being able to speak the language of the heavy-lifting side of projects. Before starting his own firm, he learned the other side working for a construction company and a mechanical contractor.

Tom Minogue

Tom Minogue

Thompson Coburn, St. Louis

Before he could make a living in law, Tom Minogue had to excel on another court. “I paid my way through college, and ultimately law school, by running my own business teaching tennis lessons” in the North County suburbs of St. Louis, he recalls. Minogue is the first graduate of the University of Missouri-St. Louis to earn a law degree at Harvard, and he’s been managing partner of the largest law firm in the city for 17 years. “I was probably the last person in my firm (back then, Thompson & Mitchell) who did a little bit of everything as a new associate,” days, he says, that are long gone for big-firm lawyers with focused practice areas. His practice concentration in corporate and banking law allowed him to counsel some of the city’s biggest companies. That’s a long way from growing up the son of a sailor disabled by a Japanese kamikaze attack. But before he died, John Minogue passed along some invaluable guidance: “Dad told me the most important thing in life is to keep your sense of humor,” Minogue says. “And my mom taught me to always do your best. I’ve always tried to do both at the same time.”

Robert O’Laughlin

Robert O’Laughlin

LHM, St. Louis

Long before the industry perks—the 3,000-square-foot suite, along with food, beverages, maid service and weekly card games with the governor and mayor—Bob O’Laughlin fell in love with the hotel business. It started with a job while he was still an accounting major at UConn, but he knew then “I wanted to become a manager.” Stints with chains large and small took him to venues like Cincinnati, San Francisco and St. Louis before he was asked to relocate to Denver. By then, he was a father, and the Missouri hook was set. “It’s a great place to raise a family,” O’Laughlin says. “And I had so many friends and enjoyed it so much, I decided to start my own company.” Thus was born LHM in 1986. Today, it has 3,000 employees, properties across St. Louis, including the impressive Union Station Hotel. All told, 5,000 rooms and roughly 1.3 million room nights a year. It’s been an intriguing career. “I got to meet a lot of interesting people—and I gave Tom Hanks his first job, as a bellman at a hotel in Oakland. I got to spend an afternoon with Bob Hope, met Bing Crosby, Ronald Reagan. It’s really an interesting business.”

Mike Parson

Mike Parson

Lieutenant Governor, Bolivar

How’s this for consensus-building in a politician: When Mike Parson was elected Missouri’s 47th lieutenant governor in 2016, he carried 110 of Missouri’s 114 counties, and secured more votes for that office than any candidate in history. Maybe that’s because he can connect with Missouri voters on so many levels—as a third-generation farmer (he still owns a cow-calf operation near Bolivar), as an Army veteran, as a former law-enforcement officer (he was sheriff of Polk County from 1993 to 2005) and as their voice in the statehouse, where he served in the Senate for six years, following a six-year run on the other side of the Capitol in the House. One of his legislative priorities is carrying on the business-development side of state policy, promoting exports and an improved climate by which companies can prosper. That’s an outgrowth of his work in the senate, where he chaired the Small Business, Insurance & Industry Committee for two years and was co-sponsor for the Missouri Farming Rights Amendment, which changed the state constitution by confirming the right of all Missourians to farm.

Gary Pulsipher

Mercy Hospital, Joplin

Nobody in hospital administration has a playbook on what to do when you find out that the medical center you led one minute has been reduced to a shell the next. Maybe Gary Pulsipher can write one. That was his world on May 22, 2011, when an F-5 tornado tore a path through Joplin. “It was a crazy time. It was overwhelming,” he says. He was at home that Sunday afternoon with family when word came that St. John’s Regional Medical Center was, in effect, gone. “It became a monumental task of how to organize, and it was a great blessing to be a part of Mercy,” says Pulsipher. “They rallied the whole Mercy team around us, but said ‘the Joplin guys in charge. We’re all working for them.’ ” Pulsipher is a native of Ogden, Utah, who fell in love with hospital work as a youth, watching the care his ailing parents had received. He and his team led the transformation of St. John’s from ruins to recovery to construction of the $345 million Mercy Hospital Joplin, which opened in 2015. It restored the city’s status as a town with two major hospitals, serving 50,000 residents and 200,000 from the tristate region who work in the area.

Karlos Ramirez

Karlos Ramirez

Hispanic Chamber, St. Louis

On the path to his career as a physical education teacher, Karlos Ramirez had a close encounter with a cadaver. And a Kinesiology textbook. “And I thought PE as going to be easy!” he says. So the native of DeKalb, Ill., called an audible—he stuck with math education and gave teaching a whirl before moving into student-activities management at Illinois State, then running the university center at a small college in Indiana. That, he said, was a lot like running a business. When the chance came to join the Hispanic chamber in 2011, he was ready; he understood way small businesses rely on the kind of work ethic his parents had demonstrated as factory workers. They’d also taught him that you don’t reach out to people just because you need their help—rather, you develop meaningful relationships. Those skills have helped him take the chamber from a staff of two—his secretary—and add employees, doubling the overall membership and growing the corporate membership by 600 percent since becoming president and CEO 18 months ago. A Hispanic business hub is emerging, he says, and “I feel like we’re making impact in the region.”

Spencer Schubert

Spencer Schubert

Sculptor, Kansas City

Lots of high school juniors fall in love. But for Spencer Schubert, the object of his affection was the silversmithing class at Shawnee Mission East. “It completely changed my life, and my senior year, I gave up the sports and spent hours and hours in the silversmithing room,” says the Kansas City sculptor. “It was the first moment I realized that there were jobs where a person could ‘make things’ all day.” It also earned him a scholarship study fine arts at the University of Kansas’ Fine Arts Department. “I have always loved the process of making things, and making clay look like people seemed like the most challenging thing for me to make in that formative late-college period,” he says. He’s the man responsible for that statue of Bill Snyder outside the K-State stadium in Manhattan, as well as towering Benedictine College monument in Atchison, and is part of the creative-class wave that has reinvigorated Downtown’s Crossroads section, There remains, he says, much to do. “I will spend the rest of my life studying this craft,” Schubert says, “and will still have a lifetime of work to do when I am done.”

Greg Scott

Greg Scott

Marquee Event Rentals, Lee’s Summit

Yes, there are long days, starting before sun is up and breaking things down in the dark of night, but for Greg Scott, the look on the faces of people after a wedding, reception or corporate event involving Marquee Event Rentals is just one way he measures success. Spun off from its roots as All-Seasons Event Rentals by the Brancato family two years ago, Marquee is part of a national group of event specialists. Given the explosion of event spaces in the Kansas City area in recent years—especially near the Downtown area—Marquee is well-positioned for growth. Scott, a Kansas City native who studied hotel and restaurant management at Metropolitan Community College, has been with the company for nearly 27 years and is now vice president for business development. It’s a good place to be. “People always looking for new and different event spaces,” he says, creating demand for tents, tables, chairs, linens, decor and systems for lighting and sound. “What I enjoy about it is the coming together of the event,” he says, “working with other vendors to create something special, have it go off just right, and at the end of the night, be able to just exhale.”

Juanita Simmons

Juanita Simmons

NW Missouri State, Maryville

Jim Crow-style segregation hadn’t yet yielded to the civil rights movement when Juanita Simmons was growing up in Wichita Falls, Texas. Young black students there were raised on what she calls “high expectations and hope.” “My parents were well-educated and highly conscious of social issues, and they raised my siblings and me to be same,” says Northwest Missouri State’s first vice president of diversity, equity and inclusion. “We were required to master Latin, the romance languages, physics, trigonometry, economics and the arts.” After starting as a high school teacher and working for 20 years in urban public school settings, she came to the University of Missouri in Columbia, teaching educational leadership and policy analysis for 14 years. She was working there during the race-driven conflict of November 2015, and draws on that experience in promoting civility and equity. That work, she says, is not empty sloganeering. “We must produce students with degrees,” she says, “but also graduates who are armed with this comfort with diversity and can take that into the workplace.”

David Steelman

David Steelman

Steelman, Gaunt and Hosefield, Rolla

He could have practiced law anywhere: David Steelman earned a degree in economics, summa cum laude, from the University of Missouri, then finished first in his class at MU’s School of Law, with the same distinction. He ended up in Rolla, a marathoner’s dash away from his hometown of Salem, and a place that offered what he wanted out of life and the law. “It’s true of most small towns,” he says of Salem, “but there was no class consciousness there, no social stratification. We all played sports together. Every job had dignity, whether the manual laborer, physician, or bank president.” He also found that science and math were particular strengths, but other than Newton’s Law, there’s not a lot of legal on that path. A course in anti-trust economics and an influential professor at MU helped pull him that direction. Litigation firms tend to be creatures of big cities, but he’s found his niche in Rolla, focusing mostly on class-actions and going up against legal adversaries from New York, Chicago and Denver, which creates a economic advantage for his clients. “My expenses in Rolla,” he beams, “are so much less than those in New York.”

Mark Steiner

Mark Steiner

GigSalad, Springfield

Growing up in New Jersey, Mark Steiner wasn’t far removed from venues like Radio City Music Hall, Broadway or big-time concerts. “This formed my lifelong passion and career,” says the Steiner, who adopted the Ozarks and found success there with GigSalad, an online talent-booking portal. “I’m a Yankee, as they say in these parts,” he confesses. A decade of work in film and television as a would-be actor, and running a craft-service company on film sets, kept him close to the industry, if not at the top of the credits. “Then I became a booking agent; that led directly into creating GigSalad with my business partner,” he says, and for the entertainment world, that was fairly innovative. “Like many inventions, it was our solution to a problem,” he says. “I was contacted by potential customers who weren’t within my business model. The volume finally exceeded what I couldn’t ignore. I wanted to be helpful, but I needed to make money in my core business, too.” He thought GigSalad would let him get back to work “doing what I thought I should be. …. I was wrong, GigSalad was right where I should be.”

Vernal Stewart

Vernal Stewart

SE3, Lee’s Summit

There might not be a better time to be a professional services company specialized in civil engineering, and there might not be a better place than Missouri. The possibilities here excite Vernal Stewart of SE3. “Missouri has the three top highways for carrying commercial growth into the 50 states,” he says, and because “smart pavements and autonomous vehicles are virtually inevitable, key players in Missouri, particularly the Department of Transportation, will need to adapt to utilize the changing technology.” Rather than pinching pennies, he thinks the state should be exploring revenue generation from the private-party applications those developments will yield. The son of a Jamaican immigrant, Stewart was born in Kansas City, educated here and did a turn at Queens Technical School in New York, where he worked on the restoration of the Statue of Liberty. Back at home, he sees plenty of lane miles of opportunities ahead. “With the I-70 corridor anchored by two municipalities in Kansas City and St. Louis that are pursuing innovation in infrastructure,” he says, “there are willing partners to embrace the technology.”

Cary Summers

Cary Summers

Museum of the Bible, Springfield

He founded the Nehemiah Group in Springfield and still has his home there, but Cary Summers’ office is more than 1,000 miles to the east since last fall’s opening of his pinnacle project, The Museum of the Bible, in Washington. This native Texan has worked for some of the biggest names in retailing and entertainment—Silver Dollar City owner Herschend Family Entertainment, for example, Bass Pro Shops and Abercrombie & Fitch. Still early in his career, he decided that “I wanted to form a for-profit ministry to help different companies.” A friend, the late Campus Crusade for Christ founder Bill Bright, “suggested I form a company that would help attract people who had never set foot into a church,” Summers says. “I took that on, and it resonated with me.” Various connections led him to the Green family, owners of Hobby Lobby, who wanted to fund their vision of a museum. Now open for two months, “it’s one of the hottest museums in town,” says Summers, the CEO, “so I guess it worked. … There is no shortage of interest in the Bible. Maybe in church or Sunday school—but not the Bible.”

Robbyn Wahby

Robbyn Wahby

Mo. Charter School Commission, St. Louis

Perhaps education came to mean so much to Robbyn Wahby because it meant so much to her father, a Greatest Generation cab driver who didn’t make it to college. “He didn’t even know anyone who went to college; it shaped him as a parent,” she says. “From the minute I was in the crib, his message to me was ‘Go to college, go to college.’ He knew the importance of education.” It has been a careerlong passion for her, through roles in public, private and non-profit organizations, including the boards of the St. Louis school district and the National Association of Charter School Authorizers. She also was the education adviser for former Mayor Francis Slay, a role that saw 28 new public charter schools. It hasn’t been easy. “People who are in something that has been traditional, and frankly functioned well for most, aren’t really comfortable going through a change process,” she says. “For traditional school districts, it feels like conflict.” So her focus is on students, and outcomes. “If there are a lot of kids not getting to what they need, don’t we owe it them, to their future and their way of life to make sure every kid has a shot at the American Dream?”

Annette Weeks

Annette Weeks

Missouri Western State University, St. Joseph

For someone whose life is framed by entrepreneurship, Annette Weeks didn’t come into it without assistance. The former grade-school teacher credits her brother, who says, “pulled me into the entrepreneurial world” to start an antique mall with 40 vendors on the town square in their hometown of Savannah. But—as often is the case—one thing led to another. Next came the 400-vendor Jesse James Antique Mall, then a craft mall, then a convenience store in that complex. Having a second set of twins turned out to be her exit strategy from the business, and after a 14-year run, she sold her half to her brother. That led her to Northwest Missouri Enterprise Facilitation for seven years, then to Missouri Western’s Craig School of Business, where she has been director of entrepreneurship since 2014. “What I do is nurture and encourage other people’s dreams, but balance that with educating them and helping them understand the reality of business,” she says. “Rural people aren’t willing to take the risk as much,” she says. “They’re very concerned about how people could judge them by the success of their business.”

![]()

Marjorie Williams

Marjorie Williams

Sisters Circle, Kansas City

When her family moved from Chicago in 1963, Marjorie Williams got a history lesson—by living it. As a fourth-grade at the former Ashland Elementary, she remembers, “they had not started the busing process of integrating the Kansas City school district.” Riding a bus each day to Central High, then Westport, she saw things a ninth-grader ought not witness—National Guard troops in the streets, and rioting aftermath on the 39th Street corridor. “Some of it we didn’t understand,” she says, “but we knew enough to understand the importance of what was going on.” It sparked her interest in the civil-rights movement, neighborhood activism, and, coming from a family of educators, a career as a teacher, then an administrator. She served for 22 years in the Hickman Mills district, 12 of them as superintendent. She retired in 2012 but has remained active in non-profit work, on the boards of Teach for America, Crittendon, Freedom Schools and the Black Archives of Mid-America, and most recently helped found Sisters Circle, recruiting women to help fund causes benefitting African-American girls.

Nancy Zurbuchen

Nancy Zurbuchen

Small Business Administration, St. Louis

American small business is undergoing a transformation, with more of them being owned by women, and in the four-state region around Kansas City, they have more than just an advocate in Nancy Zurbuchen: She’s been where they are. Freshly appointed as Office of Advocacy’s Region 7 Advocate, she’s a Smithville native who lived the small-town childhood—4-H, marching band, drum majorette—and the big-city entrepreneur’s life in Kansas City as founder of Communication by Design and later, Motional Multimedia. Over the years, “I continually worked to better the business climate for women, minority, and small-business owners,” she says. “I came to understand that the most effective way to do this is to be engaged in public policy, at all levels of government.” By signing on with the SBA, she says, she continues to act on her passion, and helping small business as regulatory reform unfolds. Her division is the watchdog on Capitol Hill to advance the concerns of small business to Congress, the White House, the federal agencies, she says: “We are the best kept secret in government, and I’m out to change that!”