HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

There is no shortage of inquiry—by sociologists, medical researchers, or non-profit developmental advisers—into the reasons why people give away their money, donate their time or contribute their talents to innumerable causes and needs. Invariably, that research tends to trace the roots of philanthropy to the same sources: because it improves one’s self-worth, expresses gratitude for blessings not universally shared, or addresses a cause close to a donor’s heart or aligned with his passions.

Less understood is why some give so much more than others. What compels people to do far more than just open a checkbook? What calls them to service in the field, to roll up their sleeves after the disaster, to actually break a sweat or risk life and limb on behalf of causes they hold dear? We might never know. But one thing is for certain: We can learn from their examples, be inspired by them, and in many cases, do the same.

Comparatively few of us will ever be able to write the seven- or eight-figure checks that make headlines for philanthropic generosity. But all of us can, at some very basic and personal level, do more to make a difference in this world. That’s been the inspiration for Ingram’s Local Heroes awards over the past two decades, and more recently, for our Corporate Champions awards. On the pages that follow, we hope each of you will find something inspirational in the stories of this year’s honorees.

Our Local Heroes awards spotlight eight individuals who serve their passions for numerous causes in impressive fashion. Please join us in congratulating them for this recognition, and in thanking them for service that truly is above and beyond the call.

Public service and private charity go hand in hand for Scott Burnett. For the past two decades, he has served as a member of the Jackson County Legislature—and before that, in public-sector roles that stretch all the way back to Washington. The legislative work is generally business attire, but several days each week, Burnett is in blue-collar mode, driving a truck for Operation Breakthrough, making diaper runs for Happy Bottoms, or serving a robust list of other non-profits that includes True Light, Amethyst Place, Bridging the Gap, Troostfest, the Nazarene Church, the Westside CAN Center, the Troost Alliance, Metropolitan Lutheran Ministries, Bishop Sullivan Center, the Pilgrim Center on Gilham and the Roanoke Park Conservancy.

Public service and private charity go hand in hand for Scott Burnett. For the past two decades, he has served as a member of the Jackson County Legislature—and before that, in public-sector roles that stretch all the way back to Washington. The legislative work is generally business attire, but several days each week, Burnett is in blue-collar mode, driving a truck for Operation Breakthrough, making diaper runs for Happy Bottoms, or serving a robust list of other non-profits that includes True Light, Amethyst Place, Bridging the Gap, Troostfest, the Nazarene Church, the Westside CAN Center, the Troost Alliance, Metropolitan Lutheran Ministries, Bishop Sullivan Center, the Pilgrim Center on Gilham and the Roanoke Park Conservancy.

Last spring, he added perishables to his cargo runs, picking up bread and distributing it to four or five nonprofits on Friday afternoons. It all started, he said, almost six years ago with a call to Operation Breakthrough, offering up some furniture that a neighbor wanted to contribute. “They had a big truck, but no driver, and six years later, I am still driving that truck,” he says. He transports appliances, furniture, beds, household goods and clothes to the mothers of children at Operation Breakthrough.

Such service is part of a larger world view framed by his work in the public sector. Raised on a farm in south-central Kansas, he started in politics even before earning his political science degree from K-State—for U.S. Rep. Bill Roy and for George McGovern’s presidential campaigns. “From the time I was a little boy, I’ve had an interest in public affairs and public service,” he says. “My mother and father instilled into me a strong ethic of helping one another.” That work eventually led him to a Democratic Party dinner in Topeka in 1975, where he met a fellow name of Jimmy Carter.

“Wow, what a change that meeting would be to my life,” he says. He went to work on Carter’s presidential campaign the next year, and joined the White House staff in the scheduling and appointment office the day after Carter’s inauguration. The life-changing continued there, as he met a girl from Georgia named Rhonda, whom he married in 1981, after the Reagan revolution that inspired a move back to the Midwest.

“In our 27 years in Kansas City, I have been very involved with the community, mentoring many young people who want to enter public service, volunteering with environmental conservation groups, and a number of nonprofit agencies,” Burnett says. “I believe that any successful operation takes two types of people: one to create a plan, and one to carry out the plan. I’m good at carrying out the plan.”

For Kevin Connor, signing on with the Amy Thompson Run for Brain Injury at its inception 30 years ago wasn’t just a charitable act: It was personal. Connor, senior vice president and general counsel for AMC Entertainment, had grown up with Amy Thompson and gone to Visitation School with her. He shared the shock that overwhelmed her family, friends and the community at large after she was shot in the head during a robbery on Halloween night in 1986; he shared their grief when she died three years later, at age 26.

For Kevin Connor, signing on with the Amy Thompson Run for Brain Injury at its inception 30 years ago wasn’t just a charitable act: It was personal. Connor, senior vice president and general counsel for AMC Entertainment, had grown up with Amy Thompson and gone to Visitation School with her. He shared the shock that overwhelmed her family, friends and the community at large after she was shot in the head during a robbery on Halloween night in 1986; he shared their grief when she died three years later, at age 26.

When a benefit road race was first proposed, Connor was immediately on board. He gives Molly Scanlon Beebe credit for organizing the run 30 years ago, but he’s been helping drive its success—and pulling on the running shoes to participate with up to 1,600 other contestants—for three decades. “I was in the cohort that helped get it off the ground, but I’m more pragmatic,” Connor says of his role with the race. “I know how the trains get to where they belong on time. Are we going to have security for this run, will we have enough money to put it together—that kind of thing,” he says.

His duties over the years have pulled him in whatever direction organizers needed—for the first decade, with logistical challenges like determining a route for the course, then for the past 20 years or so, applying his skills and connections to fund-raising and development. This year’s race was the last to bear Amy Thompson’s name. A full generation has passed since her death, and at the family’s request, the title has been sunsetted.

But Connor will be back next Memorial Day when it rebrands as the Going the Distance for Brain Injury Run at Loose Park. With his help over the years, the race has raised an estimated $2.5 million to benefit brain-injury patients and their families through the Brain Injury Association of Kansas and Greater Kansas City.

A not-insignificant chunk of that money came from Connor and his wife. “I’m blessed to be able to contribute financially, and blessed to be with a company that has generous matching funds for charitable donations,” he said of AMC, which at one point had a match of up to $12,000.

Getting to know the other organizers, contestants and even beneficiaries has been enriching, he says, noting the case of one honoree who later took his own life—depression being a frequent companion of brain trauma. “To have known him, learned about his depression, that leaves a lasting impression,” Connor says. “It validates why you’re doing it: to give the families the support and the resources to avoid something catastrophic like that.”

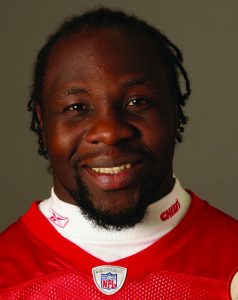

It is, perhaps, the greatest bit of understatement you’ll hear from anyone in 2017: “My upbringing was very difficult, not the typical upbringing as a regular American kid,” says Tamba Hali. And that’s a fact: Hali spent the first decade of his life in his native Liberia, during a tragic time of civil war. He then escaped that setting by coming to America when he was 10, and was reunited with his father, who was teaching at a small college in New Jersey. It didn’t take him long to embrace American culture, particularly with sports. Young Hali learned to play football, and play it well. He earned a scholarship to Penn State, where he became an All-American defensive end. And since 2006, as Chiefs fans well know, he has been the scourge of NFL quarterbacks, racking up 89½ career sacks. But he never forgot the conditions that defined his childhood, and despite the comparative wealth of America, he sees need here. After the Chiefs drafted him, running back Larry Johnson connected Hali with a woman familiar with Kansas City’s non-profit scene and linked him in with various charities. Among those efforts, Hali in recent years has gathered children from the reStart homeless shelter and taken them shopping for presents at Christmas. “I didn’t grow up on gifts and being able to celebrate Christmas earlier in my life where something is being given to me,” he says, explaining the motivations for those trips. “I feel like because I am in the position now and am able to help, helping kids and inspiring them and giving them hope—for me, I think that’s huge because giving back to them and enjoying that time of the year and celebrating it, most of them usually don’t have that opportunity. And the fact that God’s blessed me.” It is, on a very personal level, paying forward a debt. “The fact that I’m able to give back, it makes me feel better because the people that helped me from where I came from to now, we really didn’t ask, these people just took it upon themselves in different parts of my life and helped,” Hali says. Over the years, Hali has also donated his time and support to Heart to Heart International, Harvesters-The Community Food Network and Toys for Tots, among others. But he has a penchant for personal involvement. “Every year, I try to help the community out, doing different charity work,” Hali says. “I usually do Thanksgiving, I help with a local church. I help with reStart and a women’s homeless shelter,” he says. “I’m blessed to be in this position and I can help. It makes me feel good.”

North America comprises 22 nations, and the poorest of them— by a wide margin—is Haiti. The abject nature of poverty there, on a level that makes Honduras and Nicaragua comparatively prosperous, calls out to many a humanitarian worker, but especially to health-care providers, Elizabeth Wickstrom is among them.

North America comprises 22 nations, and the poorest of them— by a wide margin—is Haiti. The abject nature of poverty there, on a level that makes Honduras and Nicaragua comparatively prosperous, calls out to many a humanitarian worker, but especially to health-care providers, Elizabeth Wickstrom is among them.

An Omaha native, she came to Kansas City 30 years ago to start her practice in obstetrics and gynecology. In 2004, she and another physician, Stan Shaffer, co-founded the Global Birthing Home Foundation. “Our desire was to connect donors and volunteers with a passion for health-care access equity to a health center that delivered high-quality women’s care with compassion, strictly followed protocols, had 24/7 access and demonstrably excellent outcomes,” Wickstrom says.

That’s a tall order for a foundation with a staff of two, especially in Haiti, where it took root, blossoming into an organization with a global aim with Maison de Naissance locations around the world. “Haiti is truly the poorest country in the Western hemisphere,” Wickstrom says, “so the need is unfathomably great. What physicians find gratifying is that their efforts over a short time in an area this resource-poor can lead to rewarding, immediate results for their patients.”

It’s also easy to get to in short order, maximizing the time investment that providers put into the work. But it’s work with a special reward. “The people of Haiti are warm, resourceful, grateful, generous, resilient, friendly gracious,” she says. “I could go on, but suffice it to say that once you have set foot on Haitian soil and met her people, you want to stay connected, and return again and again.” Maison de Naissance has now delivered more than 5,000 babies with zero maternal deaths, Wickstrom says, “but the way we are changing the world is by transforming one donor or volunteer heart at a time.”

Her work hasn’t been just sweat equity; she also contributes financially. Although she prefers to give anonymously, something learned from her parents, “it’s also important to lead by example,” Wickstrom says. “Global Birthing Home Foundation is not the only organization my husband and I support, but of all the causes I have encountered, this non-profit is the most scrupulous at accounting for where our dollars are spent, that the programs are true to the mission and vision of the Foundation, and that the work truly saves lives every day. What better use for the money that I am privileged to make as a high-risk obstetrician could there be?”

It started this way: Back at Pittsburg State University, John Lair took a recreational therapy class where the professor had offered extra credit to anyone who volunteered at the local Special Olympics Spring Games. Lair, a Pittsburg native, took him up on that offer— and found a new direction and a new purpose in life. “I truly thought I would be there an hour or so—I was there all day,” Lair remembers. “I just felt a feeling of belonging. All the athletes were having fun and it was true sports. Everyone cheering for their competitors and loving life. I was hooked after going to my first track meet.”

It started this way: Back at Pittsburg State University, John Lair took a recreational therapy class where the professor had offered extra credit to anyone who volunteered at the local Special Olympics Spring Games. Lair, a Pittsburg native, took him up on that offer— and found a new direction and a new purpose in life. “I truly thought I would be there an hour or so—I was there all day,” Lair remembers. “I just felt a feeling of belonging. All the athletes were having fun and it was true sports. Everyone cheering for their competitors and loving life. I was hooked after going to my first track meet.”

What followed over the next quarter-century has been a love story for the philanthropic ages. Lair would go on to distinguish himself as one of the most dedicated—and successful—coaches in Special Olympics history. He achieved coaching certification in 16 different yearround team and individual sports, serving as the head coach for the New Hope Bulldogs Special Olympics team in Pittsburg for 16 years, competing 50 weeks a year.

How did that work out? He was the 2016 American Health Care Association Hero of the Year, 2015 Advocate of the Year for the state of Kansas, 2016 Pittsburg State University Outstanding Alumnus, winner of the All-Stars Among Us award from Major League Baseball and People Magazine, the 2014 Special Olympics North America Coach of the Year (out of 190,000 coaches), he created partnerships with Chiefs and Royals, and he helped bring a world-class gym to Pittsburg, exclusively for people with disabilities.

And now, as they say, The Rest of the Story: Last May, after 21 years of working with New Hope, John Lair was offered, and accepted, the role of president and CEO of Special Olympics of Kansas. “I feel like I get so much more from the athletes than I give back to them,” says Lair, who logged an astonishling 2,000 volunteer hours last year alone, on top of his work with various teams at New Hope.

“They truly have taught me so much about life. I have learned to not take myself so serious and to not sweat the small stuff.” The real attraction comes from experiencing the authentic appreciation of the youngsters he’s helping. “The athletes of Special Olympics are so accepting of others and they don’t judge others,” Lair says. “We can learn a lot from that way of thinking. I truly feel a warmth in my heart hanging out with the athletes and many have become part of my family.”

Bill and Cynthia Kelley were looking ahead to a 40th wedding anniversary in 2010, pondering exotic locales with ocean views. That Jan. 12, a 7.0-Richter scale earthquake hit the Caribbean island of Haiti, where Olathe-based Heart to Heart International has long done humanitarian work. A friend of Cynthia’s asked if Bill might b e willing to do some volunteer work there; he figured a couple of weeks there would be a nice change from the golfing routine of early retirement.

Bill and Cynthia Kelley were looking ahead to a 40th wedding anniversary in 2010, pondering exotic locales with ocean views. That Jan. 12, a 7.0-Richter scale earthquake hit the Caribbean island of Haiti, where Olathe-based Heart to Heart International has long done humanitarian work. A friend of Cynthia’s asked if Bill might b e willing to do some volunteer work there; he figured a couple of weeks there would be a nice change from the golfing routine of early retirement.

“I fell in love with the country and people,” he says. He worked hard not for two weeks, but for two months to help maintain food, lodging, safety and transportation for medical volunteers streaming in to help. Cynthia was asked to survey properties and determine feasibility for laboratory construction, since virtually all Haitian medical laboratories had been destroyed or damaged. “We spent our 40th wedding anniversary in the Caribbean,” she muses, “but not quite the way we had imagined.”

That’s how they have become “the uber-volunteers any nonprofit organization would love to have,” says Heart to Heart’s CEO, Jim Mitchum. Just this year, he says, Cynthia installed medical labs in seven locations, and Bill was still in Houston in November, providing logistics support to the organizations operations after Hurricane Harvey’s devastation.

The Kelleys—high school sweethearts from their days in Sand Springs, Okla.—have lived in Leawood for 23 years. While they both volunteer for Heart to Heart, they don’t always work in the same settings. Since 2010, Bill has made 14 trips to Haiti, serving more than a year combined. He also led a medical team into the ravaged Southwest coast following Hurricane Mathew, while Cynthia has made five trips to establish medical labs and conduct workshops on laboratory management standards, delivered lab testing equipment to a cholera treatment center, and trained staff. They volunteered last year for a two-week rural health initiative in the Missouri boot heel.

“While they may have potable water and indoor plumbing, basic health-care services are absent in the five counties that comprise Missouri’s bootheel,” Cynthia says, “and the unemployment rate is shocking.” Still, says Bill, even though “it sounds cliché, there is no better way to gain an appreciation for the abundance in America than to serve on mission trips outside the U.S. We take the basics for granted every day—clean water, medicines, food to eat, clothes to wear, streets and roads to travel on.”

Following the earthquake, Cynthia says, “the devastation in Haiti was heartbreaking, but we soon learned that most of the population was already suffering poverty unlike anything we could imagine and oppression that had no reference point in our world.” It’s all part of an irresistible calling. “We are taught to live out our faith in God by helping others,” Bill says. “It is a privilege to have the continued opportunity to serve in any way we are able.”

Nearly half a century in banking taught Tom Holcom plenty about what it takes to bring things into proper balance. But by his reckoning, there’s a moral ledger in this life, too, and it needs just as much attention. When he started working in Kansas City in 1972, he says, “I needed my own mission and values compass.”

Nearly half a century in banking taught Tom Holcom plenty about what it takes to bring things into proper balance. But by his reckoning, there’s a moral ledger in this life, too, and it needs just as much attention. When he started working in Kansas City in 1972, he says, “I needed my own mission and values compass.”

Peering over a life horizon to what might be written on a tombstone, nothing seemed quite as compelling as “He Made a Difference.” He set out to do just that, volunteering with banking-education organizations, until a friend invited him to a board meeting for Big Brothers-Big Sisters of Greater Kansas City. Holcom thought it might be a great opportunity to be a Big Brother. “Things were going well in my career, and I had no children,” he recalls. Sure: He’d check it out.

Impressed by the presentations at that meeting and by the organization’s dreams, he asked a few penetrating questions—and ended up being invited to join the board. “I was looking for one kid, but I ended up with all of them,” he says. The ability to make a difference was intoxicating. “I became passionate about what the organization was doing, and knew, that this was a place where I could make a bigger contribution. Talent, time and treasure are the things people talk about; maybe this is the organization that gets all three of mine.”

His affiliation with BBBSKC ran for more than 30 years, including time as board president. A signature accomplishment was launching Bowling for Kids’ Sake, which became a pinnacle fund-raiser, routinely yielding $500,000 or more. “It was a life-changer for the organization and the numbers of Bigs and Littles we could serve,” he says.

On his way to becoming chairman and CEO of Pioneer Financial Services, he also became the second president of Angel Flight Central and helped found Angel Flight America, learned to fly himself and started ferrying chronically ill children and their families to treatment centers across the nation. (That’s him with a young passenger, above.) And he was also part of the volunteer team that generated the funding to keep the flame light atop the Liberty Memorial, among many other civic and charitable ventures that have called him to serve.

Following his 2014 retirement, he became a strategic adviser for Giving the Basics, which provides personal hygiene products, that aren’t covered by food-assistance programs, to low-income homes. “They’re doing tremendous things with a unique business model,” Holcom says, because Giving the Basics has the four elements that made it impossible for him not to sign on: Synergy, energy, passion and skills. “They are passionate about what they do, and are doubling what they’re doing annually.”