HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

At that point—before the financial meltdown of September 2008, before the full impact of the housing bubble’s burst had been realized, before the recession that started in December 2007

was deep enough to even be classified as one—Mike Lammers and Scott Thompson took the entrepreneurial plunge.

“We knew if we could make it in this economy, we knew we’d be well-positioned to capitalize on that.” -Mike Lammers, Tricension

They started an IT company. In some respects, their new company, Tricension, was born into the worst of times. Lammers and Thompson entered a sector bursting with entrenched competitors. They had only their personal resources to draw

on, no deep pocketed investors. And business executives were slamming the brakes on non-essential expenditures as fresh economic data confirmed the nation’s worst fears.

That’s when a harsh reality set in at Tricension, along with a line-in-the-sand mentality: “Failure,” Lammers says, “was not an option.” It would be their operating standard in the first

year. Tricension was able to scratch out close to $400,000 in revenue in 2008, but there definitely were lean times. For a number of months, neither took a paycheck. “We’re a services company,” Lammers says. “No one wants to bank on a services company. We didn’t have a product at that time. It was high-risk, you put your own credit out there, your house, port-folio, whatever. We just decided to gut it out.”

But somehow, Lammers just …knew. “It was not easy,” he says. “Not at all. But we knew if we could make it in this economy—and I don’t think it has turned yet to the degree where business owners are comfortable making investments—we knew we’d

be well-positioned to capitalize on that.”

And so they have it, tentative as the recovery has been. In 2011, Tricension crossed the million-dollar revenue mark, good enough to earn the No. 12 spot on this year’s Corporate Report 100 list of the fastest-growing locally headquartered companies in the Kansas City region. Making that list in the company’s first year of eligibility carried with it a measure of pride for Lammers, who spent 15 years at Cerner Corp., learning IT infrastructure and entrepreneurial thinking, and Thompson, a veteran programer who had worked with him later, at H&R Block.

Lammers credits vertical-thinking skills for seeing them through: “A lot of people see a problem, don’t have a solution, and throw their arms up,” he said. “The first tenet on our cultural list is ‘Figure It Out.’ This organization is filled with people who are figure-it-out people, and those who couldn’t are no longer in the organization. It takes perseverance; a culture that says ‘This is personal. I’m not going to go home tonight until I have figured it out.’”

Tricension is one of 16 companies to crack the CR 100 for the first time in 2012. At the far end of the success spectrum is Cary Daniel, CEO of Nextaff, this year’s No. 1 company. Nextaff has pulled off something no other company has done in the 27-year history of the CR 100: They’ve finished No. 1 twice. And this, after a runner-up showing last year.

Only a small measure of irony is at work with Daniel’s explanation for the company’s success. The very same economic conditions that made Tricension’s debut so challenging were fueling the

need for the services of companies specializing in work-force solutions—everything from recruiting and staffing to payroll and separation services. That, and a series of well-timed acquisitions, drove Nextaff from its 2008 base of $6.8 million all the way to $84.5 million—up 1,128.55 percent in that period. What’s up

with that?

“I’d love to tell you it’s because we’re the smartest guys in world,” Daniel said. “Most of it, though, is because we’re in the right business climate. Our business does very well in times of optimistic uncertainty.”

Both companies are part of several trends that show up in an analysis of the 2012 CR 100 entries. Most noticeable was that the decline in growth rates for No. 100 on the list had been reversed after a steep three-year slide. In 2009, the final company into the mix had grown nearly 75 percent between 2005–2008. By last summer, that had plunged to just over 20 percent. This year, it headed up—not by a lot, at 27.45 percent, but up nonetheless.

In addition, the number of companies reporting growth of at least 100 percent for this reporting period surged by nearly 40 percent, from 21 to 29. But perhaps most significant of all is that, for 2011 revenues, Big went Bust: Firms making the list this year were, overall, significantly smaller than last year’s Top 100. The aggregate 2010 revenues of the 100 fastest-growing companies on the 2011 list came to $30.84 billion. This year? They combined for $24.55 billion. A lot of big firms that had made it into the field in previous years, even robust economic years, didn’t come close to matching their previous growth levels.

All of that is particularly significant, notes Larry Lee of Northwest Missouri State University, because of what smaller companies, particularly high-growth start-ups, mean to the overall economy and job creation in a nation stuck above 8 percent unemployment for nearly four years. Lee, a business development specialist in technology and commercialization for Northwest’s Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, previously held a similar position with UMKC, so he’s well-acquainted with the impact of small, high-growth firms in this region.

Fitting perfectly into that dynamic is Tricension. From zero to 17 jobs in four years, the company has been hiring when competitors have been treading water. It has done so by bringing an innovative approach to IT infrastructure needs, taking a whole-business view of a company’s technology requirements to differentiate itself from that established competition.

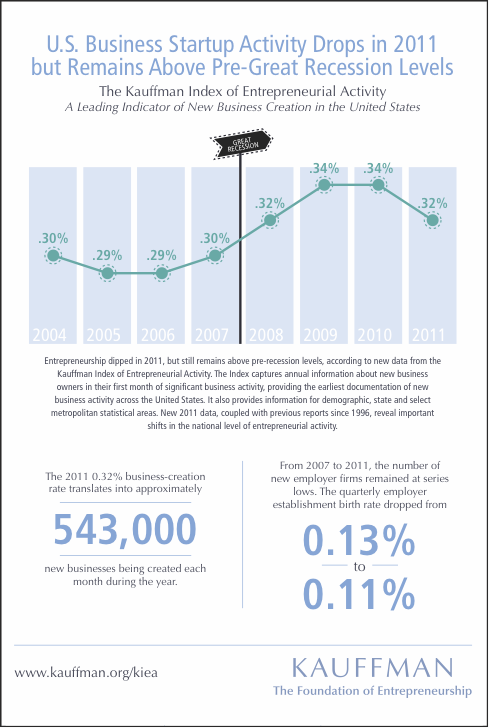

“Innovation matters to our economy, locally and nationally,” Lee said. He cited the work of the Kauffman Foundation’s analysis of fast-growth companies as evidence:

Those figures, said Joel Wiggins, director of the Enterprise Center of Johnson County, should inform public policy and private investment decisions throughout the region.

“You have to hit a lot of singles, doubles triples, as well as home runs,” Wiggins said. “Kansas City, frankly, has done a really good job creating some of those companies. I think what’s also interesting in the region is that Missouri and Kansas are at the forefront of taking research that the Kauffman Foundation has done and building it into enlightened legislation at the federal level.”

The best example of that, he said, was the Start-Up Act, introduced in Congress by senators and representatives from both states earlier this spring. Among other things, preliminary versions of the act would create a new visa classification for up to 50,000 foreign students with advanced degrees from a U.S. university science, technology, engineering or mathematic disciplines, another for 75,000 immigrant entrepreneurs who employ at least two full-time employees, a permanent 100 percent capital gains tax exemption for investments held for at least five years in “qualified small businesses,” research and development tax credits for new firms, and a review of regulatory practices that discourage start-ups.

The best example of that, he said, was the Start-Up Act, introduced in Congress by senators and representatives from both states earlier this spring. Among other things, preliminary versions of the act would create a new visa classification for up to 50,000 foreign students with advanced degrees from a U.S. university science, technology, engineering or mathematic disciplines, another for 75,000 immigrant entrepreneurs who employ at least two full-time employees, a permanent 100 percent capital gains tax exemption for investments held for at least five years in “qualified small businesses,” research and development tax credits for new firms, and a review of regulatory practices that discourage start-ups.

“It’s really important to help get these companies launched, and to get them to the point where they bridge the gap from innovation to revenue and profitability,” Wiggins said. “And it’s important to remember that the bulk of new, higher-paying jobs are created by companies like these. Not all job creation is equal, and some of the jobs we’re talking about here pay two or even three times as much as the average job in our area. That has

to weigh in as well.”

Daniel, of Nextaff, said that in the national competition for job-creating companies, Kansas City is well-positioned. His own firm has undergone multiple acquisitions that have extended operations into Florida, North Carolina and Texas, but Kansas City remains the choice for the company’s headquarters, he said.

“For us, there are a lot of factors: The quality of the people, the work ethic, the cost of living,” Daniel said. “What everybody says when they come to Kansas City—and we poll people from all over country, potential partners, potential hires—what everybody likes about this place is it has the feel of a large city, the benefits of major-league sports, the entertainment and cultural amenities, without the negatives of congestion, the traffic, high cost of living and of housing. It makes it very appealing to people to look at Kansas City for a place to live; it makes it easier to recruit.”

Those assets, plus the city’s well-documented penchant for entrepreneurship, are tangible difference-makers, he said.

“People are willing to take advantage of that,” Daniel said. “I think we have a real advantage over most other places.”