HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

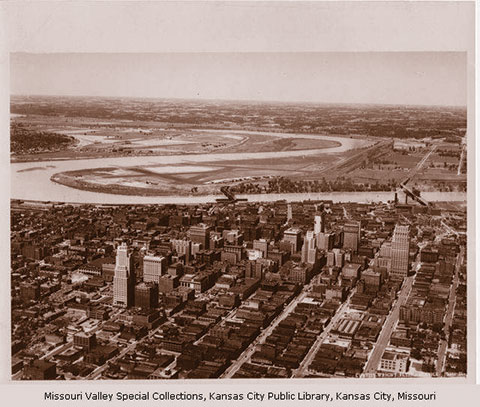

When Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “Hitch your wagon to a star,” he could have been talking to the pioneers who went all the way west in the 1830s, to a curve in the Missouri River where the town of Kansas was just forming. Almost 175 years later, the town, now known as Kansas

City, is the center of a sprawling metropolis of 2 million people who live in 16 counties straddling the state line.

We Kansas Citians may not know all the details of our history, but most of us do know that Lewis and Clark stopped by for three days in 1804 on their way to find a water route across the country. Clarke wrote that Kaw Point, eventually designated as Kansas City, Kan., would be a fine place for a fort and had plenty of elk, deer, buffalo, bear and parakeets [now extinct here]. Now you can walk across the Town of Kansas Pedestrian Bridge, which links the City Market to the Downtown Kansas City Riverfront [start at the north end of Main].

We Kansas Citians may not know all the details of our history, but most of us do know that Lewis and Clark stopped by for three days in 1804 on their way to find a water route across the country. Clarke wrote that Kaw Point, eventually designated as Kansas City, Kan., would be a fine place for a fort and had plenty of elk, deer, buffalo, bear and parakeets [now extinct here]. Now you can walk across the Town of Kansas Pedestrian Bridge, which links the City Market to the Downtown Kansas City Riverfront [start at the north end of Main].

That spot marks the city’s birthplace, two railroads, and the Missouri River floodwall.

Not much was happening here then, unless you were a Native American; by 1810, there were only 19,783 people living in Missouri—and most of those were in St. Louis. By 1821, Missouri, as part of the Louisiana Purchase,

had become the 24th state, a slave state by the terms of the Missouri Compromise. By 1853, with 2,500 residents in the town of Kansas, the first City Council meetings convened—councilmen received $2 for each meeting they attended. One decision eventually was to rename the city to its current appellation in 1859.

War… and Jesse James

At about the same time, the Kansas territory was opened for settlement by the federal government. Both pro-slavers and abolitionists dashed in to settle, trying to establish whe-ther the state would be a free or slave state. The free-siders won. This was a huge issue, with most Jackson Countians [the Missouri side] opting, and fighting, for slavery.

Skirmishes followed between the pro- and anti-slavery forces in both Missouri and Kansas for six years before the Civil War began. Jesse James and brother Frank, whose father was a Baptist minister and helped found William Jewell College, were Confederate guerillas from nearby Kearney in Clay County—an area that had more slaveholders than any other region of the state. The guerilla war increased in velocity and fierceness as the “Jayhawkers” and “Border Ruffians” slugged it out during the war. It climaxed in the horrific slaughter known as the Lawrence Massacre—Confederate leader William Quantrill’s attack, in which Jesse James probably rode—on the town 40 miles to the west of Kansas City. That led to Order No. 11, which allowed Kansan troops to “eliminate sanctuary and sustenance” for pro-Confederate guerrilla fighters pretty much however they wanted. In the words of one observer, “The Kansas-Missouri border was a disgrace even to barbarism.”

After the war, Jesse James became an outlaw, robbing banks and stagecoaches before turning to trains. He pillaged with his James-Younger gang all around the Midwest and Texas and West Virginia. He was boldly murdered and his shooter immediately exonerated by Gov. Crittenden in 1882. [See Jesse James Home Museum in St. Joseph.]

After the war, Kansas City grew and prospered, mostly because it had won the commission for the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad bridge over the Missouri River, besting a town twice its size—and one with a fort, at that—up the river in Leaven-worth. When that opened in 1869, the town’s size quadrupled. The Missouri Pacific railroad, steaming into town in 1865, was the first of several lines that turned Kansas City into a hub—the second-largest train center in the country, a title it retains today.

Cowtown

By 1871, the famous but now defunct Kansas City stockyards were alive with thousands of cattle, herded here because of the good grass on the way to the city’s central location and ease of transportation to points east. The Kansas City steak was born here, and to this day, one had better not ask for a “New York strip”—glares and harrumphs will likely result. The Cowtown label remains pretty accurate—there’s still the giant Hereford in Mulkey Square at Summit and 13th Street, once the headquarters of the American Hereford Association. The American Royal, begun in 1899, still thrives; and you can still get the best steak ever in a number of area restaurants.

By the 1890s, Kansas City was a real city, population 133,000, when the first of the Pendergasts came into power. Two brothers—James, an alderman, and Tom, superintendent of streets and then a City Council member—and their influence and power played a significant role in shaping the city that they basically controlled with their version of the Democratic Party behind them.

Prohibition And Gangsters

A helpful factor in this was that Kansas enacted prohibition in 1881, but Missouri had no such restrictions. Downtown Kansas City, 12th Street especially, was the place where saloons and taverns proliferated. Carrie A. Nation attempted to swing her ax in Flynn’s Saloon in 1901, but was promptly arrested and told never to come back to Mis-souri. She didn’t.

Missouri stubbornly resisted all attempts at temperance until prohibition arrived with the 18th Amendment in 1919. Even then, despite federal mandate, prohibition never stopped anyone from drinking in Kansas City, thanks to the Pendergast machine. They probably regarded the famous remark of the editor of the Omaha Herald, “If you want to see some sin, forget about Paris: Go to Kansas City,”

as a tourist promotion. All vices flourished, as well as the cement industry [see Brush Creek] and social welfare in exchange for loyalty and a vote, under the Pendergasts, much to the dismay of the Republicans and the editor of The Kansas City Star, William Rockhill Nelson [see the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art], and crime was rampant. Tom Pendergast and his “Goats” were responsible for Harry Truman’s first position as judge in the eastern district [see his museum and home in Independence].

But alcohol and politics alone didn’t fuel Kansas City’s reputation during this area. Crime was rampant—some would say endorsed. The Mob was mostly alive, well, and thriving during the Pendergast regime.

Al Capone stayed at the Rieger Hotel [eat there, drink downstairs at 19th and Main], the Hotel President [see the now Hilton at 1329 Baltimore for great pictures and “relics”] had a speak-easy and tunnels to smuggle in bootleg booze, the Bellerive Hotel at 214 East Armour heard Frank Sinatra sing and Liberace play for Capone and assorted guests. The Union Station Massacre in 1933 firmly established Kansas City’s “fame” when four local and FBI agents and a criminal were slain as a gang tried to free the criminal. [Go to Union Station and check out the “bullet holes.”] This bloody event changed the FBI

forever, the government granting agents authority to arrest criminals and carry firearms.

But just to prove the mob, and the mafia, weren’t gone completely from Kansas City streets, the River Quay area, formerly called Westport Landing [the first incorporated district of Kansas City], was redeveloped in the 1970s. A mob war developed and three buildings were burned or blown up. Residents then weren’t quite so eager to walk, wine, or dine there, and the area remained blighted for some time. Today, however, the area, now called the River Market, is safe and inviting with residential lofts, restaurants, coffee shops [see the new, old Kansas City Opera House], bars and businesses and several not-to-be-missed spots [see the City Market and Steamship Arabia Museum].

Jazz

Certainly another result of the bars, speak-easies, and taverns being allowed to exist was the rise of Kansas City jazz and blues from the 1920s on. The atmosphere was right, the opportunities plentiful in Pendergast’s “wide-open” town in the ’30s which attracted musicians from all over the country.

It is said that there were over 50 jazz clubs on 12th Street. They’re gone, but the flavor is alive still on 18th and Vine [see the Jazz Museum, the Blue Room, and the Mutual Musicians Foundation] where it was considered the hot spot for African-Americans especially and some of the best music around. Charlie Parker began his road to fame here and he and others like Joe Turner, Bennie Moten, Count Basie, Jay McShann, Hot Lips Page and many others played regularly. [Sing “Goin’ to Kansas City,” our official song, now.]

Today, see if you can catch the McFadden Brothers, Ida McBeth, Joe Cartwright, Angela Hagenbach, Tim Whitmer, David Basse, Oleta Adams, or Michael McGraw’s Boulevard Big Band. There are many others who can introduce you to the different sounds of Kansas City jazz. Clubs to check out include the Blue Room, Knuckleheads, the Phoenix, Grand Emporium, and even the Ameristar Casino. Jazz is often on the menu.

By the 1940s. KC had settled into a friendly, Midwestern, serenity. J.C. Nichols had already developed, in the “southern” part of town, the Country Club Plaza out of a former swampland [well, almost] refuting his many critics’ claims that he was crazy. Designed in 1922, its Spanish architecture is the backdrop for fountains, gardens, sculptures, and even a couple murals. Oh, and it’s a place where people work and play—its restaurants, bars, coffee and other shops attract millions of visitors every year.

[Best secret parking space: just north of 47th and Wyandotte … then start walking.]

Barbeque

Barbeque back then was a backyard affair mostly, and mostly on the east side of town. It’s turned into a local industry, with about 100 restaurants and shacks serving up their own version. Each has a specialty, from ribs to sausage to fish;

each has its raving fans, for whom no compromise is possible. We can’t even decide how to spell barbecue, bar-b-q, BBQ—but we sure know we like it. Vegetarians will have to get by mostly with potato salad, slaw, or onion rings—not a very bad way to go, either.

[Try Oklahoma Joe’s, Gates, Fiorella’s Jack Stack or Bryant’s for some of the best.]

There’s much more to Kansas City fame than war, cattle, gangsters, jazz and barbecue—but you’ll have to find that out for yourself. Today, Kansas City is a tourist’s delight—whether you’re visiting or live right here. Our tag line is the “City of Fountains,” and you can go on a tour just of those, beginning with the first one at 15th and Paseo, installed in 1899. The largest urban park in the country, Swope Park, invites picnickers, athletes, zoo, nature center and theater-goers. Large pockets of shops and restaurants exist in all the suburbs, from Zona Rosa to Brookside to Over-land Park. Cultural attractions are plentiful. There’s so much to see and do in the Kansas City metropolitan area, most places, certainly those of similar size, barely compare. And yet, despite all, Kansas City was recently rated one of American’s Top Ten Most Underrated Cities by Yahoo! Travel. Go figure.