Team President Carl Peterson is not one to put a gloss on things. When he came to Kansas City in 1988, he inherited a team that had been returning to the playoffs with cicada-like precision, once every seventeen years, and a stadium that only a cockeyed optimist could appreciate for being half full.

"The fan base was non-existent," says Peterson bluntly. "We had to go touch the public."

One very effective way to reach the public was through philanthropy. Peterson made no bones about his intentions. He inserted an addendum in all new player contracts mandating at least five gratis appearances at relevant events.

Not surprisingly, some player agents resisted. They had no way of assessing the addendum's value beyond dollars and cents. The players themselves, however, caught on in a hurry. This, Peterson anticipated. He had been around the game long enough to learn something about human nature, and what he learned was this: People like to do good.

"The minute they got involved," says Peterson of the players, "they found out how much they enjoyed it."

Tony Richardson could sense the difference between the Chiefs and his former team, the Dallas Cowboys, the first week he arrived here in 1995. "It amazed me to see the amount of guys involved in the community," says Richardson. He quickly took their lead and made a prophet out of Peterson. "Man," he declares emphatically, "I enjoyed this."

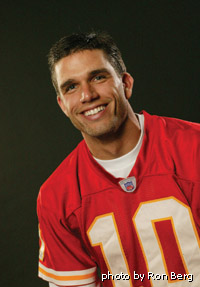

Richardson and the three other players pictured on Ingram's philanthropy edition front cover--Will Shields, Trent Green and Priest Holmes are just four out of the many Chiefs who deeply and genuinely involve themselves in the community. Despite Peterson's hard-nosed observations, one badly under- estimates these players and their teammates to think they do it for the sake of public relations or to shelter income. If there is a "selfish" reason involved, it is that they, like Richardson, truly enjoy what they do.

One does not typically link the words "enjoy" and "philanthropy," but several of the Chiefs used the word freely, and it makes sense. To some degree, everyone who participates in philanthropy does so because they derive pleasure from it, because it makes them feel good.

"We feel blessed and gifted to be in the position we're in." -Trent Green

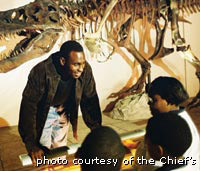

A pro football player, however, derives a deeper, more immediate level of satisfaction than the average mortal. When, for instance, a player walks into the children's wing of a hospital, eyes light up instantly. Trent Green observes that the real pay- off of being Trent Green, NFL quarterback, comes when he "sees the smiles on the kids' faces." Green can't help but to smile himself at the memory of it. Athletes have a magic about them that other people, team owners and mangers included simply don't.

This much said, why it is then football players, Chiefs in particular, dedicate so much more heartfelt energy to their good causes than do other young adults with star power like, say, musicians or movie stars? The answer lies in the culture of sports in general and in the culture of the Chiefs in particular. And the calculus goes well beyond pleasure.

When asked, several of the Kansas City Chiefs on this month's cover volunteered the same one word to describe the reason for their commitment to the community.

It's a word that would not surprise you except that you rarely, if ever, hear it in other fields where people achieve wealth and celebrity at an early age. Nor do the players express the word by rote or by can't or as a well-oiled gesture to placate the front office. No, when they say it, they mean it. The word is too personal not to.

That word is "blessed."

"We feel blessed and gifted to be in the position we're in," volunteers quarterback Trent Green. Trent and his wife Julie work through the Trent Green Family Foundation, which focuses on families with chronically or terminally ill children or seniors.

"God has truly blessed me," says Chiefs fullback Tony Richardson, explaining his own community commitment. A bachelor, he jokes that the front office never hesitates to call him with assignments because "T-Rich never says ‘no.'"

"T-Rich never says ‘no.'" Tony Richardson formed his"Rich in the Spirit Foundation" in 2000 to help individuals that society has turned its back on.

Richardson so seldom says "no," in fact, that this year he was awarded Pro Football Weekly's Arthur S. Arkush Humanitarian Award. Although the magazine is a weekly, this prestigious award is given out but once a year and to only one player in the nation. Richardson is only the fifth player to win. The first winner of the Arkush award was Chiefs' all-pro offensive guard, Will Shields.

If these players feel "blessed," it may be because football breeds a degree of genuine humility. Both Priest Holmes and Trent Green know that what stands between them and obscurity--literally--are people like Tony Richardson, Will Shields, and the other less celebrated players on the offensive line. Football is the ultimate team game. There is no individual success on a poor team.

Green and Holmes have a first hand acquaintance with obscurity. Green entered the league as the 222 pick in 1993 and did not get to throw a pass in an NFL game until 1997. Although he was named offensive player of the year in the NFL last year, Priest Holmes broke in as an undrafted free agent in 1997 and served as a role player in Baltimore for four years before finding his star in Kansas City. Tony Richardson also joined the league as a free agent and spent his first year in the NFL, 1994, on the Dallas Cowboys' practice squad. For that matter, Will Shields came to Kansas City as only a third round draft pick.

Tony Gonzalez has sponsored a program for sick children known as Shadow Buddies.

Football players know too just how precarious life can be. Trent Green survived a devastating knee injury that cost him the entire 1999 season, a starting position in St. Louis, and very nearly his career. This past off-season, Kansas City held its collective breath to see just how well Priest Holmes would recover from hip surgery. Given the tenuousness of their own careers, players tend to appreciate more what they have and empathize with those who have less. They also tend to pray more. Compare, for instance, the references to God at next year's ESPYs and next year's Oscars. There will be no comparison.

For all that, the only saints in the NFL play for New Orleans, and their sainthood rarely extends beyond the name on their uniforms. The temptations in the NFL to do wrong are at least as powerful as those to do right, perhaps more. Witness, for instance, the recent 60 Minutes confession of hall-of-famer Lawrence Taylor.

If any one player has embodied the Chiefs' spirit in the Peterson era, it was the Chiefs' best and best-known player, the late Derrick Thomas. Although not immune to the outsized temptations the game offers, there was no doubting Thomas's heart, either on the field or off of it. He would read to kids in the library on Saturday mornings and often show up unannounced in children's hospitals, distributing presents and spreading his warmth. The NFL named Thomas "Man of the Year" in 1993, and President George H. W. Bush designated him Point of Light number 832. He also started the Third and Long foundation and a tradition of commitment that has lived beyond him.