The Doctor is … Out?

Decades after the warning bells first sounded on a decline in physician ranks, multiple factors are conspiring to downgrade U.S. health care to critical condition.

by Dennis Boone

A full generation ago, The New York Times, Fortune and, naturally, the Journal of the American Medical Association were blaring headlines about a looming shortage of physicians in the United States.

A full generation ago, The New York Times, Fortune and, naturally, the Journal of the American Medical Association were blaring headlines about a looming shortage of physicians in the United States.

Who could have known then that by 2012, health-care providers might be looking back on those as the Good Old Days? Since then, physician shortages have become even more acute in some specialties, in particular with the entry point to health care for many Americans: the general practitioner. A dramatic overhaul of the nation’s health-care system has done little to allay those fears—and may have exacerbated them.

Jeffrey Kramer assesses the ranks of physicians and observes: “We don’t have enough—and it’s going to get worse.” He speaks not just from his perspective as a cardiac surgeon at the University of Kansas Hospital, but president of the Metropolitan Medical Society of Greater Kansas City.

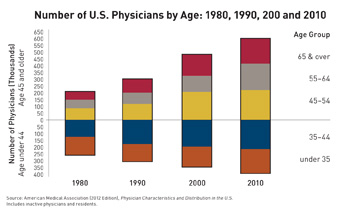

Multiple factors, health-care providers note, have compounded a longstanding problem. For one, the educational pipeline isn’t big enough to replace the cohort of physicians on the cusp of retirement. A national study not long ago projected that 60 percent of Kramer’s peers in cardiac surgery alone planned to retire within a decade.

Another challenge, following the Supreme Court’s decision this summer to uphold the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, will be the addition of millions of people under health insurance coverage in 2014, without a corresponding increase in doctors to see them.

“To bring people into the insurance system without thinking about who’s going to provide the care is not a good idea,” says Kramer, who also notes the prospect of looming cuts in federal graduate-school assistance that helps pay for physician residency programs.

Nor do the structural challenges stop there. Thomas McAuliffe, a policy researcher for the Missouri Health Foundation, said the economic stimulus package of 2009 added a major complication. “Most people don’t know it, but ARRA had lots of funding in there for health information exchanges and electronic medical records, with requirements for physicians to move to EMR if they see Medicaid and Medicare patients,” he said.

“Most rural physicians live on Medicare. We don’t have any data yet, but anecdotally, we’ve heard from physicians and people in rural areas that physicians are retiring” rather than deal with the cost and complexity of electronic systems at that stage of their careers. “They’re saying, ‘We want nothing to do with this,’ ” McAuliffe said. “It’s a significant problem.”

For Kansas City, a region that prides itself on both the quality and quantity of health-care providers, the situation might not be as dire right now, said Jill Watson, executive director for Metro Med. But it could be soon.

“There’s no evidence it’s not going to be as bad or worse” than projected, Watson said, “The demographics are still the same in terms of aging, and the physician population is still the same—they’re aging too. Lots of doctors in their 50s have already started thinking, ‘What’s the next part of my career going to look like?’ And it probably isn’t in the operating room or in full-time practice.”

She pointed to a 2008 Metro Med study—soon to be updated—that showed a high percentage of physicians anticipated retiring within five years. That was at the cusp of the recession and a subsequent market downturn, which prompted many to defer those plans. But now, their retirement windows are five years narrower.

“I think as soon as people financially can pick that back up, they’re going to get out,” Watson said. Like Kramer, she notes that you can’t just replace them all with a new cohort: “It takes 12 years to train a new doctor,” she said, and despite the best efforts of medical schools in the region—Kansas City has three of them—they don’t produce adequate replacement numbers, and the numbers they do generate aren’t meeting the specialty needs.

There’s more to the replacement calculus, as well: Physicians coming into practice today are less likely to embrace the kinds of hours that have long been a norm for doctors. Moreover, as more women enter medical schools, the issues of career and family loom larger. We’ll simply need more doctors to tread water if there are more female physicians who will take time off to raise children, Watson noted.

All of those factors may be cause for concern, but there are upsides in some of the policy changes, professionals say. One is the focus on increasing the badly thinned ranks of primary care physicians; another is the money that’s going into bolstering preventive care by covering annual checkups, with a goal of saving both hard dollars and physicians’ time as longer-term benefits.

“Some things in ACA make primary care more appealing than has in the past,” Watson said. “There is a focus on some of the funding and innovation” directed at primary care, she said, and those efforts, “could make or break that specialty, honestly.”

Another trend line in health-care delivery is the increasing importance of nurse practitioners, who could help physicians deliver more effective care by working with patients that don’t require the services of a doctor.

“There certainly is an increasing number of nurse practitioners in a variety of settings, including hospitals, but also in community-based and industry settings,” said Karen Miller, dean of the school of nursing at the University of Kansas School of Medicine. “And nurse practitioners in particular are certainly helping us extend the continuum of health care to more people, more conveniently.”

For years, she said, the school has been addressing the need for more nurse practitioners with upgrades in its programming, as well as in other areas. The increasing demand for medical services, she noted, will not just be driven by health-care reforms, but by another megatrend: Roughly 80 million members of the Baby Boom generation who have started crossing the retirement-age threshold of 65.

That, Miller said, will create a significant demand “not only for nurse practitioners, but for all allied health providers.”

Watson said nurse practitioners, advance-practice nurses and physician assistants soon could be making patient referrals directly to specialists. Kramer, like many physicians, expressed concerns about the potential for overlooking conditions that a trained primary-care physician might pick up. But both acknowledge that the so-called “extenders’’ would be vital for helping make more efficient use of a physician’s time.

A recent trend in general practice, the family-centered medical home, embraces that approach, using extenders alongside trained physicians, Watson said, and those practices are finding innovative ways to wring inefficiencies out of health-care delivery.

Kramer and Watson also said there were encouraging signs with the wellness programming pieces of health-care reform. “Hopefully, it will give people coverage so that they can visit doctors before it gets to be a life-threatening problem that they have to go to the emergency room for,” Kramer said. “To some extent, it’s a societal problem, not a physician problem. I think a lot of insurers are looking toward incentivizing people to take better care of themselves.”But a decided minority in the health-care field believe that the federal reforms will bend the health-care cost curve downward. That’s especially troubling to physicians, Kramer says, because even though they account for only about 20 percent of health-care expenditures, they’re easy targets for policymakers.

“The thing that doctors are worried about is that the budget is going to be balanced on the providers’ backs, on physicians, because we have the lowest amount of resources and voice when it comes to policy-making,” he said. With insurance companies and large hospital networks commanding armies of lobbyists, “the way debate is being framed is that physicians need to take a pay cut. But we’re the ones actually providing the health care.”

That’s particularly galling for someone who spent more than a decade in residency, training grounded in 80-hour work weeks today, but considerably more in the past.

“You have to go into it for the right reasons,” he said, assessing the appeal of a medical career. “Going into it for economic reasons is not a good idea. But having said that, you have to make a living.”

And even then, the financial rewards come at a cost. “My kids, two teenagers, they don’t want anything to do with medicine,” he said. “I think a lot of it is, they don’t see me a lot.”

And at a time when the nation looks to restock a diminishing medical cupboard, the hidden cost of lost opportunities like that can’t be calculated.

Return to Ingram's September 2012