Taking Graduate Courses to a New Degree

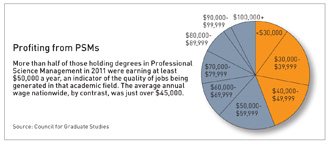

Universities in Missouri and Kansas are moving quickly to embrace Professional Science Master's programs—and companies in the Kansas City region's life-sciences sector may reap the rewards.

by Dennis Boone

They’re big. They’re organizationally complex. And major public universities aren’t particularly known for being able to turn on a dime when it comes to changes in programming.

But there is indeed a programming prairie fire moving through U.S. universities, and it’s building in intensity in Missouri and Kansas: Here comes the Professional Science Master’s degree, 15 years old in concept but just a few years into a programming explosion that promises to fill a critical need in scientific and research instruction. In doing so, it could not only strengthen public universities that can use those programs to capitalize on instructional niches, but stock big businesses and small start-ups alike with skilled scientists who bring a decidedly whole-business view of the world to their laboratories.

“Many of the people who take these are already in a profession; they’re not intended for the typical 22-year-old,” said Tom Heilke, dean of graduate studies at the University of Kansas. “They’re intended for practicing professionals who want to hone their skill sets.”

Whether you think of it as a kind of MBA on scientific steroids or a science degree that has been run through the business-school wringer, the PSM is rapidly gaining traction. While some elements might be offered as certificates with 12 hours of coursework, the PSM itself generally consists of two years of study in a scientific field, culminating with an internship in a real-world business setting. That scientific rigor is supplemented with instruction in business finance, operations, project management, communications, and regulatory affairs.

“You come out of school with a bachelor’s degree, and that can be a great degree, but it’s very general,” Heilke said. “It can make you employable, but as people move along in your career, things become more specialized, so having that masters level of instruction can be very valuable.”

One interesting aspect is that virtually all of the programs are being development in collaboration with local or regional employers to ensure that students emerging with a PSM can transition seamlessly into the work force. That could have profound implications for efforts to expand a healthy—but still relatively young—life sciences presence in this region.

One interesting aspect is that virtually all of the programs are being development in collaboration with local or regional employers to ensure that students emerging with a PSM can transition seamlessly into the work force. That could have profound implications for efforts to expand a healthy—but still relatively young—life sciences presence in this region.

The concept behind these degrees emerged in 1996, when the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation began working with elite research universities to formulate a new approach to graduate-level instruction. The goal was simple: Break down the walls of silos that had long separated corporate research functions from the boardroom. By moving business considerations farther upstream, into the lab itself, companies could pivot more quickly to follow promising leads and push new products into development and commercialization.

A few years later, the Council of Graduate Schools signed on as a partner in the effort, then in 2006 assumed the duties of promoting the initiative. More than 100 universities now offer degrees in at least 200 disciplines. Writing in the Chronicle of Higher Education, the Sloan Foundation’s Michael Teitelbaum and Carol Lynch of the graduate schools council said that “to our knowledge, this rapid growth of a new degree concept is unprecedented.” Nearly as remarkable, they noted that the spread of PSMs was taking place even with American universities mired in financial stresses.

The upshot of all this? Regional universities are exploring ways to add a potentially high-demand arrow to the educational quiver. Universities in Missouri are crafting a comprehensive strategy that will allow state-funded institutions to capitalize on their areas of specialization, while sharing resources with sister institutions to provide graduate students access to a broad base of programs.

At the University of Missouri, said graduate studies dean George Justice, there are two related efforts: One on campus to be an umbrella PSM program, and one that dovetails with other schools in the state, not just the UM system, bringing together graduate deans and faculty members who are exploring ways to use share the local programming strengths of each campus with other institutions, using on-line resources.

“We’re trying to create ways for various universities—like MU, with our research programs, 7,000 graduate students and 34,000 students total—can connect with places like Missouri Western or Southeast Missouri State, who may have areas of expertise they can piggyback onto shared coursework.”

But while the movement is racing forward nationally, schools in Missouri are taking a deliberate approach to rolling out PSM programs, he said. “We don’t have a date at which we know we’ll have PSMs up and running,” he said. “It’s more important to do this the right way than to slap something together.” But Justice said he would like to have something concrete in place by 2014.

“We’re excited about the possibilities of this program,” said Charles McAdams, Justice’s counterpart at Northwest Missouri State University. “There’s an almost unprecedented collaboration of state universities at work, so we’re all sort of studying this, in essence, so that we can share the courses.” A student at Northwest, for example, might be able to take courses through various institutions, so that the burden of implementing the programs isn’t borne by any one school.

And Northwest can tailor such a program to fit with its other strengths, complementing them and reinforcing its emerging role as a source for graduates in the animal-health corridor. “We have a tremendous resource in the Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, with labs there now, the nanoscale-science program, and our traditional emphasis in biology and animal health,” he said. “So we’re look-ing for opportunities within that realm.”

In Kansas, universities have begun rolling out their own PSM courses or closely related versions that reinforce each school’s mission. Kansas State University currently has one program designed like a PSM, said Dean Carol Shanklin of the graduate school in Manhattan. It’s a professional master of technology, offered through the Kansas State–Salina program for the past two years.

“It has all the features—core courses, communication, project planning, key components that counselors from graduate schools have identified as essential for success within different industry segments,” Shanklin said. She also noted that K-State is taking a similar approach in reviewing all graduate programs at the masters level to incorporate many of the skill sets found in PSM instruction.

KU, likewise is laying the groundwork for a broader PSM structure, starting in environmental assessment and project management. Funded with proceeds from the Johnson County Education Research Triangle sales tax, KU’s Edwards Campus in Overland Park is exploring 10 new degree programs in business, engineering, science and technology, all to be launched within a few years.

The emergence of the PSM track has been abetted in part by cutbacks in traditional corporate training programs, creating an opportunity for universities to be, in effect, an outsource for broadening an employee’s skill set.

“Some corporations can take care of that in-house, but we have additional expertise in communications and management areas, so students can avail themselves to get a level of training and skills that companies themselves are not able to provide,” said KU’s Heilke. That makes the programming particularly valuable to smaller organizations without deep HR pockets—like the “gazelles” that the Kauffman Foundation says are essential to job creation because of their history of rapid growth.

And those are exactly the kinds of companies that have been driving the steady growth of the life-sciences sector in this region.

But crafting a new program that infuses a science degree with non-science course work has to be done in ways that don’t dilute the value of that underlying scientific instruction, educators say. “This is not ‘Science-Lite,’” said MU’s Justice. “Most science learned in a lab in a traditional program will become obsolete in just a few years with advances in science. What we’re trying to teach are habits, skills and familiarity with processes for those who aren’t familiar with them in the first place.”

Most PSM structures are able to walk that fine line between science and business because they’re focused on creating a new kind of employee. Grad school deans say traditional masters-level instruction in science disciplines will continue; PSM is merely a new wrinkle in a range of educational offerings.

“That’s really what this is about,” said Northwest’s McAdams. “This is for someone who is already a scientist to not only get more expertise in a particular area of science, but a healthy dose of management and supervisory formal training. That goes along with an internship to make them more marketable or much more valuable to an employer.”

Eventually, he said, a PSM holder might be at the level of setting corporate policy, but that’s not what most students in that track are looking for—otherwise, they’d probably be pursuing an MBA.

“This is about being a lab manager or division manager, not necessarily setting direction for the corporation as a whole, but responsible for managing a team that may be working on large projects,” McAdams said. “They have to be able to work with a prospectus, with a budget, with training, hiring and supervising employees—all of those things where the work gets done.”

The push for quick PSM development, said K-State’s Shaklin, was also being generated by forces off-campus. “One reason this has had such a trajectory is that emphasis that many states are placing on workforce development,” she said. “There’s a greater awareness for preparing students for the work force, and that’s why you see this collaboration between higher education, state agencies looking at work-force development and industry.”

One asset that makes large universities valuable—tenured professors who bring rich experience to their campuses—is also one reason why program modifications can be like turning a battleship on a sea of molasses. So a basic challenge of fully embracing the PSM movement is that “faculty in the past have been trained to do two things: research and publish,” said Denis Medeiros, dean of graduate programming at the University of Missouri–Kansas City. “Consequently, there is a gravitation for faculty to serve those students who are after a traditional masters or PhD. It’s harder to get them excited about professional master’s degrees.”

Part of the battle, then, is developing a cultural change within the academic faculty to engage more in preparing students for positions other than pure research, Medeiros said.

“One of the reasons for that inertia is, faculty at most institutions have largely been judged not only on teaching, but on their research output. So they are highly dependent on graduate students who do their thesis and dissertations—they usually drive a faculty members’ publication record, which is very important for tenure and promotion.”

So universities must ensure that faculty members receive credit for engaging new degree programs. As it turns out, federal budget tightening—those grants drive a large amount of research—could compel faculty members to embrace changing program structures they otherwise might have resisted. “The grant dollars are not there like they used to be,” Medeiros said.

Other factors, said Justice, are contributing to the pace of change.

“Partly, it’s because we have younger faculty who are much more open to moving back and forth between industry and academia,” he said. “At the same time, there is a crisis in the academic job market. Traditional degrees, being research-oriented and preparing the next generation of research faculty, that market has dried up.”

Return to Ingram's September 2012