Once upon a time, students going to a state-funded university paid a portion of the total costs for their four-year degrees, but taxpayers subsidized the bulk of that expense—75 percent or more. The policy consensus was that the state would more than make up on its investment with a highly trained work force that would be attractive to new and growing businesses. Each graduate who stayed in state would prime a revenue pump spitting out payroll taxes for decades and generating economic activity that benefited all.

Those days may indeed seem like fairy-tale settings now. Over the past three decades, as university costs have vastly outstripped growth in state funding levels, the proportions have changed, and are very nearly inverted from the old model. Depending on the state and university, students these days can expect to pay two-thirds to three-fourths of college costs. Many of them are leaving school with debt loads of $20,000 or more. And we’re not talking about high-dollar, post-graduate medical or law schools, but liberal-arts programs issuing baccalaureate degrees.

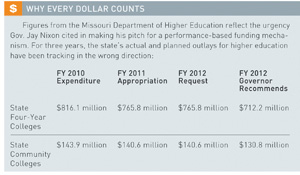

That, says Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon, is a recipe for economic disaster. Last month at the Missouri Higher Education Summit, he made a pitch for a new educational funding model. It would not follow a familiar pattern of routine budget increases soon accompanied by crisis-level cutting; instead, it would demand that universities demonstrate measurable success in turning out the kinds of graduates who can keep the state’s economy thriving. He cast the need for that change largely in economic terms, citing the correlation between education level and such factors as earning potential and unemployment rates. He also noted the advantages that come with a well-educated work force when a business is deciding where to build, expand or relocate.

Brenda Norman Albright, a Nashville-based consultant, provided attendees at the same assembly with information showing that more states were looking to their public universities to bolster economic development in the same way. Key measurements of substandard outcomes driving that movement:

• Graduation rates for four-year institutions have stalled at 58 percent.

• More than 75 percent of students who start at a community college fail to earn a certificate or degree within three years.

•America’s next generation of workers, those now 18 to 24 years old, are less well-educated than those 25 to 64 years of age.

Nixon’s call for a new formula didn’t escape notice outside Missouri’s borders. At the Kansas Board of Regents offices in Topeka, officials are trying to assess what such a change could mean for their own programs and student-recruitment efforts, but a representative of the office declined to comment, citing lack of specifics in the Nixon proposal.

Nixon applied some broad brush strokes of his financing proposal, but a task force of administrators from around the state will have to provide structure and detail to those. It’s still too early, educators say, to sense which universities might benefit from performance-based funding, because there isn’t yet an answer to the question “Performance in what?”

One member of that task force is John Jasinski, president of Northwest Missouri State University. Such a change could benefit the Maryville campus, he said. “We’ve been operating on a performance-based model anyway for number of years,” he said of Northwest Missouri State, “but performance-based funding overall? We’re supportive of that.”

The benefits, he said, “are many, relative not just to the higher-education sector, but to the taxpayers. For the sector, for those performing, it would show that we continue to perform and do well and receive funding; for the taxpayer, it would show that higher education is delivering on its promise.”

Much will ride, though, on specifics.

“If you only focus on one type of metric in lieu of others, say the quantity kinds of measures, with the number of graduates being one example, you need to look at both quality and quantity,” Jasinski said. “You have to take a balanced approach, as you would with metrics applied across various sectors.”

Of particular importance, he said, was factoring in the varying missions of state universities. “We all have similarities, but we all have specific missions that we deliver for the state,” he said, and the goals need to reflect that so that no university is put at a disadvantage before the first measurements are recorded.

Still, other educators say the early framework for discussions could mean that state universities that now apply greater selectivity to their admissions are more likely to benefit under the plan. Truman State, for example, is the only state school considered “highly selective” in admissions, one level above the four University of Missouri campuses and Missouri State University.

Open-enrollment schools, by contrast, could find it harder to succeed under a performance-based system because they are required to accept students who haven’t demonstrated the same levels of academic achievement. Among those are Missouri Western in St. Joseph and the state’s community colleges, including Metropolitan Community College in Kansas City.

Nixon has restated familiar goals for raising the numbers of degree holders, culling some programs to achieve greater efficiencies and adding others to meet work-force needs, and fostering collaborative efforts between institutions, especially with technology-related programs. That’s been pretty standard fare in higher-education agenda-setting; structural changes to the funding mechanism hold greater potential for changing the way the system works.

“Your funding model must recalibrate the balance of state budget appropriations, tuition and cost reductions,” Nixon told campus execs. “That will make your budgeting process less crisis-driven, and funding levels more predictable from year-to-year.” He also said the funding model had to change because of the student debt burden.

“You can’t afford to buy a car, or buy a house, or start a family if your job barely pays enough to cover your student loans and rent,” Nixon said. “We need to get out ahead of the ‘education bubble,’ and change our funding model before it bursts—sending students in search of cheaper, but inferior, alternatives.”

Already, the task force he created is seeking ways to bring greater accountability to university funding, emphasizing goals and the metrics to measure them, but focusing primarily on results.

Under his approach, a 5 percent increase in state appropriations for higher education overall would translate into a funding increase of 5 percent for a school that met all of its performance goals. Conversely, hitting 60 percent of a school’s goals would yield a 3 percent increase. The four markers Nixon laid down covered student success and progress, degree completion, learning quality and affordability.

On top of that, he suggested an additional goal for each school, specific to that institution’s mission. ![]()