| |

|

|

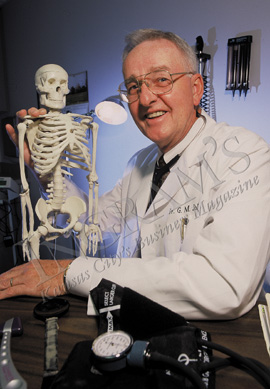

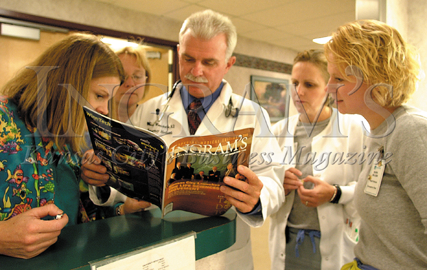

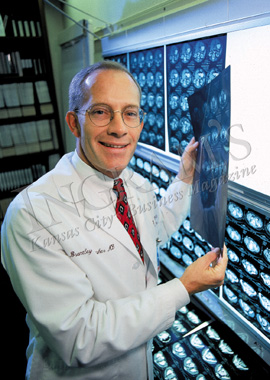

Gary

Berger

Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation

“Definitely a patient advocate who goes

above and beyond. He loves his patients and they love him.” These

glowing words were spoken about Dr. Gary Berger, D.O., who is Medical

Director, Rehabilitative Services for Menorah Medical Center as well as

Associate Medical Director for the Rehabilitation Institute.

Dr. Berger does agree that when he’s with his patients, they’re

all that matters. He chose rehabilitation as a specialty for the same

reason he chose his degree from Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine:

it’s more hands-on, more comprehensive, and a more general practice

approach—a direction he says the medical profession has veered toward

since he graduated in 1983. He is rewarded by patients whom he helps to

recover their dignity, as they turn a disability into an impairment that

they can overcome. He believes there is great compensation when his patients

are able to regain their self-respect through what he and his staff have

taught them.

He points out the rehabilitation field is only about 60 years old, when

WWII made helping people adjust to physical change a necessity. Although

diagnostic testing has improved, and functional and assistive devices

of one kind or another have advanced, the real improvements have occurred

in understanding—for instance, a better understanding of stroke and

brain-damage recovery has helped better accommodate patients at home.

Outpatient care and resources have improved, so patients can leave the

hospital earlier and their families are encouraged to participate in the

process.

Dr. Berger left private practice in 1996—a good move, he says, because

now he has more freedom, camaraderie, and people to turn to with questions.

His passion in rehabilitative medicine has deepened even further to include

dealing with the effects of cancer, the disease his wife died of a year

ago. This has radically changed his life, he says, and that of his two

children, but in ways he would not have necessarily foreseen. “My

life is first with my kids. I’m both mom and dad — and I like

my life with them,” he explains quietly. “I wouldn’t have

it any other way.”

|

|

|

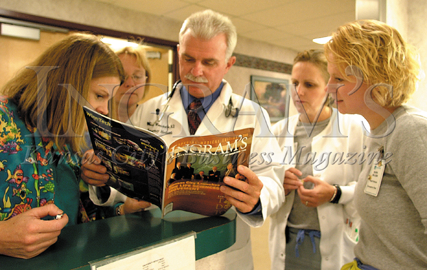

Richard

Derman

OB/GYN

People who’ve served in the Peace Corps

always say they got more from it than they gave. Dr. Richard Derman wholeheartedly

agrees, for his pre-residency stint in India created his life’s direction.

Seeing the enormous trials and pains of the women in India led him to

become an ob-gyn and then to get a degree in public health from Johns

Hopkins.

From there, his life has been one filled with research as well as clinical

success. At the University of Illinois-Chicago, he helped create the comprehensive

program that received one of 15 federal designations as a Center of Excellence

in Women’s Health.

That work moved him to Kansas City when offered the commitment from both

Truman Medical Center and UMKC to use those successful models to create

a similar center for Kansas City. This will be a concentrated and seamless

continuum of care for women, made possible by the recent $1.3 million

grant from the Hall Family Foundation. “The idea is to link the expertise

at UMKC with clinical excellence and patient base at Truman. We will be

able to play a major role in women’s health care,” he enthuses.

Dr. Derman has the Schutte Chair in Medicine Leadership/Women’s Health

from Truman Medical Centers and UMKC, where he is professor as well as

associate dean. He is one of a handful of experts whose practice is limited

to menopause, but he has been involved in research in everything from

pelvic inflammatory disease to urinary pregnancy tests to alternative

medicine. He’s written a book on fertility control and edited one

on hormonal therapy.

He says others probably call him a workaholic, but he’s really very

people oriented. Dr. Derman notes that it’s funny how things come

round—he’s recently obtained another grant from the National

Institute of Health to prevent women hemorrhaging to death at childbirth—in

India. He loves each of the components of his work—patients, research,

and collaboration. “I’m very excited about the collaborative

effort I see going on in Kansas City. I hope to play an active role.”

Given his energy level and commitment, he surely will.

|

|

|

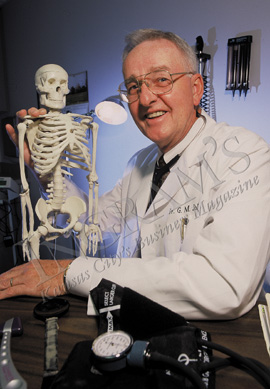

Mike

Johnston

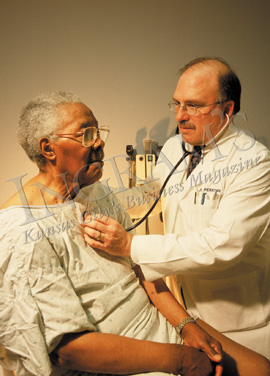

Internist

“My wife and I were married in Oklahoma

at 2 p.m. on Saturday afternoon, graduated from college at 6 p.m. that

same day, drove to Kansas City on Sunday, and on Monday morning, I started

school at what’s now the University of Health Sciences, College of

Osteopathic Medicine. That was 32 years ago and I still owe her that honeymoon.”

Dr. Mike Johnston laughs as he thinks back to his start in the field that

he knew he wanted to be in because of his grandfather and uncle, both

of whom were physicians.

Perhaps considered a more holistic approach to healing, osteopathy heeds

the spiritual and mental well being of the patient as well as the physical.

Dr. Johnston is definitely a proponent of that approach and of his university

with its new educational pavilion and classroom facilities. His day is

spent with students, residents, and patients. He greatly enjoys his teaching

on the clinical side—”the passing on of my trade.” His

joy is apparently echoed by those he teaches—he’s received “Teacher

of the Year” five times within the past 10 years for both resident

and student teaching affiliated with UHS. And he goes this month to Orlando

to receive a national award, “Internist of the Year,” from the

American College of Osteopathic Internists at their annual meeting.

But what makes him most proud and happy, he says, is to be around a great

“house staff"—the doctors, interns, residents, and staff

people with whom he works on a daily basis. “I’m so very fortunate

to be surrounded by these people in this profession.”

Now chairman of the internal medicine department at UHS, professor, program

chair for internal medicine residency out of the Medical Center of Independence,

and general internist who still is in practice, Dr. Johnston truly enjoys

all aspects of his life—practicing medicine, mentoring and teaching.

“I tell my students it’s the greatest job in the world and it

comes from the left ventricle. There’s nothing more rewarding than

doing this work, but you have to love it, you must to have a passion for

it.”

Dr. Johnston has that passion.

|

|

|

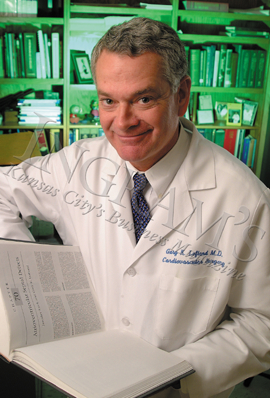

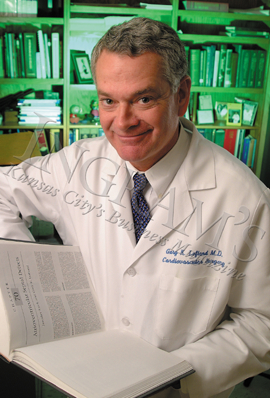

Gary

Lofland

Pediatric Cardiac Surgeon

You could probably bet that not many cardiothoracic

surgeons who specialize in congenital heart disease began their careers

on Indian reservations. But Gary Lofland, who always wanted to be a doctor,

encountered a couple of physicians while a resident at Duke University

Medical School who’d worked on reservations and recommended it. So

a young Dr. Lofland, not having defined his specialty yet, left for Montana

to run a medical center there as a primary-care physician. “It was

an amazing experience. I saw things there you wouldn’t see anywhere

except on a reservation . . . or in a third world country.”

But he left public health and went into research. He already knew he was

fascinated by surgery, especially thoracic surgery, and that attraction

led him to congenital heart disease. He thought such heart disease was

the most challenging to treat with surgery, and he still thinks so nearly

20 years later.

Dr. Lofland occupies the Joseph Boone Gregg chair at UMKC’s School

of Medicine and works more than full time for Children’s Mercy Hospital.

He operates on children as small as 450 grams up to full-sized adults

with congenital heart conditions. He works on a wide range of defects

and still finds it fascinating and rewarding. The children make up the

majority of his patients, and the most difficult thing about that, he

admits, is the emotional involvement and the extreme sense of responsibility

you feel for patients and families. “You are accepting responsibility

for an entire unlived lifetime,” Lofland says.

Doing over 500 operations a year leaves little time for hobbies—he

says his used to be “the lung"—but any free time is spent

with family, exercise, reading, or more sporadically, salt-water fishing

(“where anticipation of fishing is usually better than the fishing”).

He talks much more openly about the atmosphere and the people who create

it at Children’s Mercy, for they make a terribly risky and stress-filled

profession not just endurable, but actually fun.

“The culture starts at the top. We have highly skilled, wonderful

people here who have intelligence and joy. They share my enthusiasm. It’s

simply a great place to work.”

|

|

|

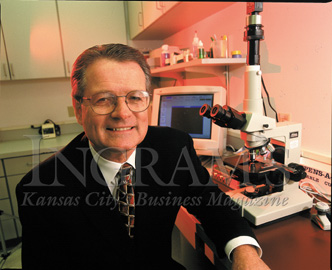

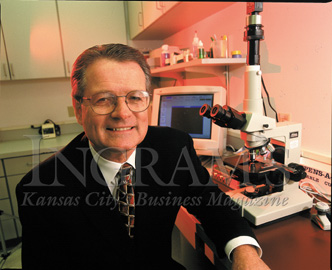

Rodney

Lyles

Reproductive Endocrinologist

“This is an art, not a science.”

So speaks Dr. Rodney Lyles about his work of creating babies from in vitro

fertilization and assisted reproductive technology. In 1988, when he founded

the Reproductive Resource Center in response to the fact that one married

couple in six confronts infertility, he knew that for half of infertile

couples, long-established medical treatment or surgical procedures could

successfully treat the problem. He wanted to work with the others.

His success rate has been remarkable, well above the national average

of 25 percent. Since the Overland Park center’s creation, there have

been over 5,000 babies born from all therapies, and over 1,600 babies

born as a result of assisted reproductive technology (ART). He attributes

that to his excellent lab, motivated donors, team approach, and the fact

that he gives couples all the information they need. “The worst thing

one can do is walk in here and say, ‘I want to be pregnant—do

whatever it takes.’ Since there are no guarantees, it’s our

job to give them all the information necessary so that they can make the

appropriate choice for themselves. That includes all the options, the

real success rates of live children born, the risks. Then they must decide,

not me.”

Dr. Lyles began as a gynecologist in Oklahoma, because he originally liked

working with a young, healthy group of people. He liked delivering babies.

Further study at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston in reproductive

endocrinology led him to an even greater satisfaction—helping people’s

dreams of having their own child come true. He speaks warmly of his staff’s

contribution to the process—”I’m fortunate to have such

a wonderful team who communicates very well and is so focused on what

we’re doing. We’ve been successful and busy because of that

focus we all share.”

He stresses that infertility programs and approaches vary widely, and

people must investigate thoroughly before they choose since it’s

expensive—and elective. “We want to absolutely do our best with

couples who couldn’t have children. If you’re in medicine, you’re

obligated to do the best you can.”

|

|

|

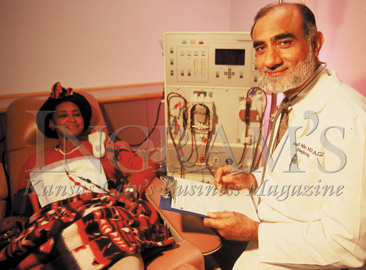

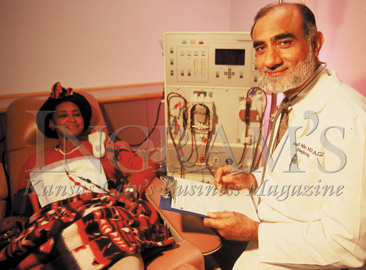

A. Rauf

Mir

Nephrologist

It was in 1972 when a young man from Kashmir

came to Trinity Lutheran Hospital to do an internship and residency in

internal medicine. He came with a couple of buddies; they were going to

do their residency, go back to Kashmir and open up a practice.

Thirty years later, Dr. Rauf Mir is still here—because the people

he worked with and admired invited him to stay for just a year or so longer

. . . and because of his faith. He was determined to build the first mosque

in Kansas City despite his knowledge that there were maybe all of five

Muslim families in the area. That project took much longer than he expected,

and that, and his love of his work, kept him in the area.

“Life just happened,” he laughs. He became a citizen in the

‘80s, and it was clear he was a Kansas City resident for good.

All three of his children were born here; his eldest daughter is a doctor,

a son is at Harvard Law School, and another son is a junior at the University

of Kansas. “I’m glad I stayed,” he says. “Kansas City

is a good place to live.”

Dr. Mir became interested in the kidneys as a specialty of internal medicine

because they involve the whole body—in order to be a good nephrologist,

you have to be a good internist. He likes the intricacies of the kidney

and its complicated physiology—and he wanted to try to master the

difficulties. “You can’t of course,” he says. “But

you can certainly try.” He is also appreciative of the advances in

this relatively recent field including more effective drugs for transplantation

and better machines and drugs for dialysis. He works on the preventative

side as well as early detection.

Dr. Mir has continued his active participation within his faith. There

are now between 7,000 and 10,000 Muslims in Kansas City, and two years

ago he was awarded the Kansas City Interfaith Council Annual Award. He

says it continues to be important “to

reach out to the rest of the community, to know our neighboring faiths,

and to help one another.”

|

|

|

J. Patrick

Murphy

Pediatric Urologist

For a guy who didn’t know exactly what

he wanted to do almost until he started doing it, Dr. Pat Murphy certainly

does a lot of it. Around 700 surgeries a year, if he were counting—which

he doesn’t. In high school (Shawnee Mission North) and college (the

University of Kansas), what he did know is that he liked the sciences,

especially biology. Going to medical school was a sort of evolution, as

was his interest in surgery. The pediatric part came about because he

worked with two pediatric surgeons he greatly admired, and from there

it was a natural selection.

“I’m manual rather than cerebral,” Dr. Murphy says quietly.

“I see a problem and want to fix it.” He found urology interesting

because there are so many obstructive and reconstruction problems that

affect the entire child. Between one and two percent of children have

some sort of dysfunction, from the simple hernia to the rare case of epispadias

(a urethra abnormality). “While the percentage is not huge, the number

of children who can be helped is,” he points out.

He says he likes the operating, the technical aspects. Recent helpful

changes have included instrumentation and sutures becoming finer and easier

to use. Anaesthetic agents have improved so outpatient care works for

more children. And laparoscopy has made its way into children’s surgery,

which has also helped. Beyond advances, though, his own personality and

drive have helped him maintain a hectic schedule whether he’s at

Children’s Mercy three days a week, KU one day, or his private practice

with six other pediatric surgeons. How does he spend his spare time? Watching

his son’s sports and doing missionary medical work in the Dominican

Republic, where a daughter is now.

What makes the hours and the lack of sleep and all the hard work worthwhile

is seeing a child you can help, he says. “The most fun is working

with kids. They’re innocent and they respond well. The younger they

are, the quicker they get better. The downside is the emotional extremes—the

children you can’t help or correct as much as you want. On the other

hand, you can often help someone for 80 years.”

|

|

|

Jane

Murray

Family Physician

“I’ve always been intrigued by what

patients tell me has worked. I’ve always listened. And I’ve

discovered there’s much more than just traditional Western medicine

that makes sense.” Dr. Jane Murray is a traditionally trained doctor

who has embraced other remedies from many different cultures. The result

is her Sastun Center of Integrative Health Care, opened in 1998, which

she characterizes as “family medicine with an open mind.”

Sastun is the Mayan word for the amulets the healers used, and it represents

the idea that healing power resides within each person. She believes that

her job is to help people find that healing power, through whatever methods

that work. Consequently, her practice includes more than conventional

Western medicine—it embraces Oriental medicine, massage therapy,

nutrition and Taoist counseling, and more. She counsels patients on healthy

lifestyle, self-care, stress management, natural herbs and vitamins.

This is all a bit of a leap for a woman whose medical degree is from UCLA

and whose background includes stints at the American Academy of Family

Physicians as director of education and then chairwoman of the Family

Medicine Department at the University of Kansas. But she decided that

she wanted to go back to relationship doctoring, not the business transactions

mandated by a health-system plan that she sees as dysfunctional. “Today

we’re forced to see as many patients as possible—get an x-ray,

get a blood test, take a pill. I wanted to go back to the doctor-patient

relationship. And now I’m happy,” she says.

She’s happy despite earning half as much as the typical family physician

and having no benefits. She maintains it’s worth it to have a more

controllable life style and a more personally rewarding practice. She

believes she offers an “old-fashioned doctor relationship with the

latest medical know-how.” She says that, “Technology has become

somehow more important than people, and the fundamental principles we

went into medicine for often seem to be lost. I wanted to try something

new, a true combination of the best of all worlds. I was willing to take

the risks.”

Her message must resonate—she has a three-month waiting list for

new patients.

|

|

|

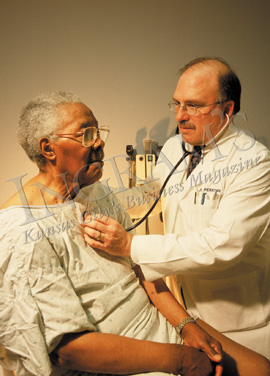

Chris

Perryman

Internist

“The number one thing my mentor taught

me was to always listen.” Simple advice, perhaps, but words that

have meant much to Chris Perryman in his chosen career in internal medicine.

“I like working with the whole person,” he states cheerily.

And so, he does a bit of everything in his day, a reason he’s stayed

at St. Luke’s ever since his residency. Daily, he sees patients,

does rounds with residents and medical students, then comes back and sees

more patients. He relishes being a diagnostician, loves the technical

advances in his field, and wants to be informed about everything that’s

going on. In his typical 12-hour day, he enjoys both teaching and his

private practice, saying, “I’m fortunate to have such a good

blend.”

Part of that blend also includes a sincere interest in physicians being

treated fairly. For 13 years he was part of a three-person practice, but

in the last nine years, he has been in a larger medical group at St. Luke’s.

“For physicians to better understand all aspects of our health-care

system, we have to be involved.” Working on numerous health-care

delivery-system activities has given him a different perspective and greater

empathy for all viewpoints. “I think I have a better understanding

of what’s going on in a system where the care is the best, even if

the financial structure is not what it should be yet.”

Another huge part of his good fortune, he says, was marrying his wife,

Kathy. She was a nurse in St. Luke’s ICU when they met 24 years ago

and is now a pediatric anesthesiologist at Children’s Mercy and mom

to four kids, including a set of nine-year-old twins. He’s very clear

that he couldn’t have done what he has without her.

Chris Perryman strikes a stranger as a supremely happy man, one who sees

that himself, as well. Plus, he says, “Kansas City as a medical community

is very fortunate. There are many excellent hospitals and physicians,

and it’s a great place to live. I’ve got the best job in the

world. The best family. I’ve got a true haven in both places. I’m

very, very lucky.”

|

|

|

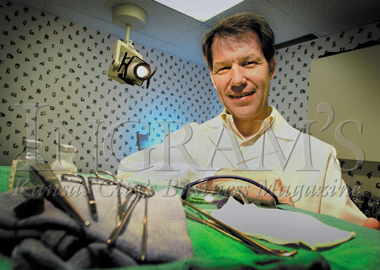

Joseph

Petlein

Laparoscopic Surgeon

The first laparoscopy, done in 1904, used

a scope, a candle and a mirror. Seventy years later, with process and

technology he helped develop, Joe Petelin began telling and showing other

surgeons how laparoscopy could make a huge difference to patients during

and after surgery. He was the first to do abdominal laparoscopy and was

determined that the rest of the world should benefit from what he had

learned. “It’s been most gratifying to see surgeons completely

change their minds once they see the effectiveness of the procedure,”

he declares.

Dr. Petelin was, as he tells it, just your normal doctor. Growing up in

Kansas City, Kan., he earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from

Benedictine College and his medical degree from the University of Kansas.

While lecturing on laser surgery, he met a guy in Nashville who was doing

a form of laparoscopy. At first, Dr. Petelin was skeptical, but then realized

its clear potential. Instead of 10-inch incisions, three inches were maximum.

Instead of a week in the hospital, three days were sufficient. While the

operation was the same, getting there was less traumatic, and thus much

easier on the patient.

Laparoscopy is now an accepted procedure, but the advanced laparoscopy

Dr. Petelin specializes in is another matter. It takes thousands of hours

to become expert at it—and that’s why he has created a yearly

fellowship that he funds with some help from corporations. It’s not

easy; it takes at least a year of concentrated study and practice. And

guidance is absolutely vital—so his specialty is growing very slowly.

Dr. Petelin sees people’s lives as a continuum. “I think in

life, each step prepares you for the next thing. Without understanding

physics, I couldn’t have made all the technical advances. Without

carpentry (his avocation) and my dad, I wouldn’t have learned how

to think on my feet and to do it right the first time. Without my college

truck-driving job, I couldn’t have judged a three-dimensional object

in a two-dimensional mirror as well. Life is usually a progression, and

each step is valuable, even if you don’t know it at the time.”

|

|

|

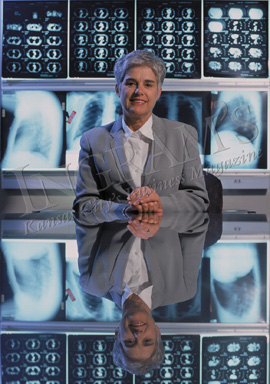

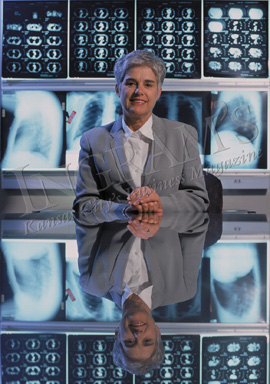

Susan

Pingleton

Pulmonologist

At just 12 years old, Susan Pingleton was

one of the first persons in the world to have open-heart surgery. There

were complications, and she was in the hospital for three months. “People

there literally saved my life,” she remembers. From that time forward,

thinking about becoming a doctor was an easy decision—she wanted

to give back.

Her specialty in pulmonology came about like so many—she had a mentor

who was a pulmonologist and he made it exciting. “We need to be mindful

of our impact on our students,” says this Jayhawker, who is an educator,

researcher, and clinician. As director of the Pulmonary and Critical Care

Division at the University of Kansas Medical Center since 1992, she still

loves her job. “I can do so many things—educate, do procedures,

research, lecture, and see patients. My life is never boring or routine.”

She is especially fond of a teaching hospital’s capability of educating

students while delivering the very best of care to patients.

One of the biggest changes she’s encountered in over 20 years in

academic medicine (she began the pulmonary division for UMKC, where she

was for five years before KU) is that medicine has become a business,

grounded in reality. “We now have to face what private doctors always

have. It’s an alien culture to us, but we’re learning to be

businesspeople as well as doctors. This is a huge problem in every academic

center in the country—but we are making progress.”

She says that becoming president of the largest clinical pulmonary organization,

the American College of Chest Physicians, has been one of the most important

and rewarding opportunities of her career. Representing the organization,

she was able to advance the causes of prevention and care, “ a good

extension of what I do daily taken to national and international levels.”

The scared young girl in the hospital clearly pursued the right dream.

Dr. Pingleton concludes, “I enjoy my life, my family, my terrific

husband, my outside activities. I have a job I love, and I hope I’m

making a valuable contribution.” It would be hard to hope for more.

|

|

|

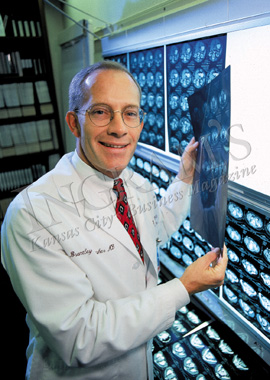

Stephen

Reintjes

Neurosurgeon

“What’s a good day? A good day for

me is when all my operative cases are going well and I can even get home

in time for dinner with my wife and (five) kids.” Between work and

family, the days and nights are full for Dr. Steve Reintjes of the Kansas

City Neurosurgery Group.

Dr. Reintjes, a Rockhurst graduate before college at Georgetown, majored

in philosophy. That study taught him he wanted a field in which he could

care for people. Medicine provided that. The neurosurgery interest came

about during his internship at St. Luke’s because, he says, it’s

precise, high risk, and intellectually challenging (which may be why there’s

only 3,000 neurosurgeons out of 550,000 doctors). After completing his

residency at

KU Medical Center, he started out in solo practice, went to a two-man

office, and then merged to form his current organization, the largest

one in Kansas City and one that works with five different hospitals. “I

do think we’ve assembled a group of good people doing good work for

Kansas City,” says Dr. Reintjes. “Our goal is simply to serve

the community as best we can.”

He’s enthusiastic about the changes that have occurred in the field.

“Today we can treat lesions and diseases safely we couldn’t

touch 10 years ago,” he says. But the part of neurosurgery he likes

the best is meeting patients, getting to know them, and taking care of

them in a time of need. He’s confident even greater advancements

will occur in treating very difficult diseases such as Parkinson’s

and potentially Alzheimer’s, which he says is more vexing than we

can imagine. He summarizes, “The brain remains elusively fascinating.”

Dr. Reintjes does not speak easily about himself, but when pushed, admits

that, besides his kids, he’s proud of his neurosurgery group. A member

of both the Brain Injury Association and the Midwest Organ Bank boards,

he also can’t underscore enough the importance of organ donation.

Since demand still far outstrips supply in organ donation, he calls it

“a generous and life-saving gift.” He’s as determined to

continue working for these important causes as for his patients.

|

|

|

J. Brantley

Thrasher

Urologic Oncologist

You would have to say that Brant Thrasher

has always been goal oriented. He wanted to go to medical school, so he

had to graduate from college with highest honors. He did. He couldn’t

pay for medical school, but the Army provided scholarships. He got one.

He wanted to study urologic oncology. A fellowship to Duke University

Medical School was the answer. He wanted to be a department chairman (once

he’d finished military obligations) and would need lots of credentials.

Consequently, he wrote, lectured, and researched aggressively.

So at age 37, when he became chief of urology at KU Medical Center, he’d

reached yet another goal–one that he’s still very happy with.

He enjoys the

combination of duties and says figuring out the best part is hard. He

concludes that, “It’s the patients. Helping them recover. There’s

nothing more rewarding than seeing someone healed of cancer.” But

he also enjoys the teaching because, in part, “It keeps me sharp

since I’m working with some very bright residents.” And then

there’s the operating, which he likes because his large reconstructive

cases require skill and precision. To add to these joys, after living

in many places, he and his family really love Kansas City.

Dr. Thrasher points out that of the 200,000 men diagnosed with prostate

cancer each year, 84 percent will live to die of old age or another disease.

Survival rates are improving due to early detection and improved surgical

techniques. But beyond these improvements, when he operated on his father-in-law

10 years ago for the disease, the human lessons came crashing home. “When

it becomes personal, it’s even more real. I try to carry that realization

with me for all my patients.”

When asked what other people might say about him, he laughs and shakes

his head. Finally: “I hope my patients would say I’m compassionate

and caring. I hope the good people I work with would say I’m an excellent

teacher and mentor. I hope the school would say I’m growing a successful

and world-class facility. If they were all saying those things, then that

would be success.”

|

|

|

Joseph

Waeckerle

Emergency Medicine

“I know it sounds corny, but when I became

a physician, I could help a few people to the best of my ability. When

I became a teacher, I could help other young physicians help them. When

I became editor of a medical journal, I could affect an entire profession—35,000

emergency physicians—and thus, their patients. As I become more and

more involved in emergency awareness on the national basis, I am affecting

even more people. The sacred trust is magnified as you try to be the best

you can for more and more people.” Joe Waeckerle speaks from the

heart.

For the last 30 years, his whole life has revolved around emergency medicine.

He says its great challenge is that you can be faced with a life-threatening

event as well as a minor one simultaneously, and you need to provide full

care to both.

He has become one of the world’s experts on medical preparedness

for weapons of mass destruction including bio-terrorism. He was in charge

of rescue triage at the Hyatt disaster and has spent the last eight years

consulting with the Department of Justice. He’s been especially busy

since Sept. 11th—a pattern he expects will continue. He’s also

always been involved in sports, volunteering his services at clubs and

high schools. He works for the Chiefs, he’s the chair for four hospitals’

emergency-care departments, he’s president of his 40-doctor practice,

he coaches his son’s sixth-grade football team, and he attends activities

of all three at-home sons.

Dr. Waeckerle, a thoughtful and expressive man, finds it “disheartening

that we live in the greatest country in the history of mankind, and we

can’t seem to provide health care for 40 million of our people. We

spend time focusing on issues that don’t improve our country. We’ve

forgotten to ask what we can do for our country.” He continues, “I

feel fortunate to be able to do my part. And that my colleagues also all

feel that we have this same sacred trust of medicine to do all we can,

to do the best we can.”

|

|

| |

|