A Productive Workforce: Employers realize benefits of Midwestern work ethic

Well-paid and well-educated, more than roughly 104,000 people transform Downtown into a vibrant center during the workday—and many are sticking around after hours.

Though many of the estimated 104,000 people who work Downtown Kansas City are drawn there because it is the center of government for the region—for federal, state, county and city or school district employees—it is also home to some of the region’s largest employers. AT&T, Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, DST Systems, and Hallmark Cards, for example, each have more than 3,000 employees working in Kansas City, most of them in the greater Downtown area.

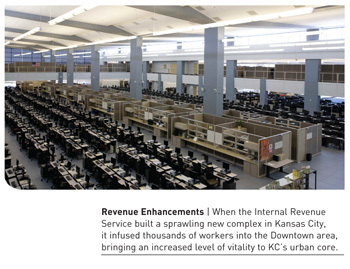

The presence of the federal government has increased exponentially over the past decade, with construction of the sprawling IRS center and coming soon, more than 1,000 workers from the General Services Administration. Even though plans for a new GSA regional headquarters remain on hold, the agency has committed to consolidating operations inside the Downtown Loop by leasing a combined 200,000 square feet of space. That move, some commercial realty professionals say, could reduce the amount of vacant office space by 10 percent.

Other major employers include the region’s two biggest locally owned banks, Commerce Bank and UMB, as well as Assurant Employee Benefits, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas City, J.E. Dunn Construction, Kansas City Power & Light Co., Truman Medical Center and the five largest law firms in the region.

In almost every case, those organizations are bringing higher-paid workers to the metropolitan core, a reflection of the higher levels of education within that work force. Combine that with the region’s long-acknowledged advantages in work ethic and productivity, and you have a baseline for business success matched by few cities of comparable size.

In recent years, the lineup of Downtown businesses—and by extension, the work force—has changed somewhat as Kansas and Missouri have engaged in a series of cross-border raids in a battle waged with business-relocation incentives. Kansas City itself has stepped up efforts to offset losses of businesses to Kansas-based programs, but the city covers a lot of ground—even when it is able to bring a business in from the west, Downtown may not be the right fit.

Last year, 17 Kansas City area business executives from each side of the state line signed a letter to the two governors—Jay Nixon of Missouri and Sam Brownback of Kansas—calling for an end to what they said was an economic arms race. They asked that each state adjust its incentive programs to focus on recruiting businesses from outside the Kansas City area. To date, no policy changes have emerged from either Capitol.

Still, Downtown has advanced its cause with development to fill some of the gaps between major projects. Among those in recent years are such notable firms as Andrews McMeel, the publishing company, architecture firm HNTB, whose Quality Hill offices overlook the West Bottoms on the western edge of Downtown, and Populous, the global designer of sports and entertainment venues.

More recently, Epiq Systems, a fast-growth company that provides digital documentation services for the legal industry, broke ground on a $7.5 million expansion of its headquarters Downtown, as did Probiotics, with a $9.1 million headquarters project. Hometown coffee merchant The Roasterie is in on the expansion act, as well, with a $5 million project that added a new contour to the Downtown skyline—a real DC-3 aircraft that now graces the plant and skyline off Southwest Boulevard, paying tribute to the image on the company’s logo.

Downtown’s advantage is accessibility to a population strewn across hundreds of square miles. No other city in the nation boasts the per-capita figure of interstate lane miles, allowing workers on most days to commute into the city with relative ease.

New infrastructure has played a role in that, most recently with the completion of the Kit Bond Bridge, a $300 million project that added another distinctive feature to the Kansas City skyline.

Next up for Downtown workers: a proposed 2-mile streetcar starter line, running from the River Market to the Crown Center district. Downtown residents in late 2012 were voting on whether to create taxing districts to fund a portion of the $100 million project, which supporters say could help generate more demand for residential units among young, educated Downtown workers.

Return to Ingram's November 2012