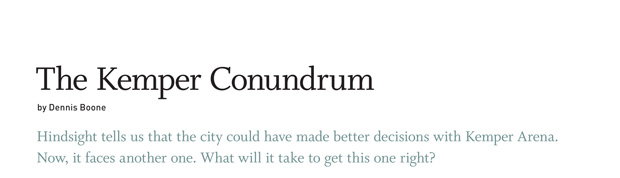

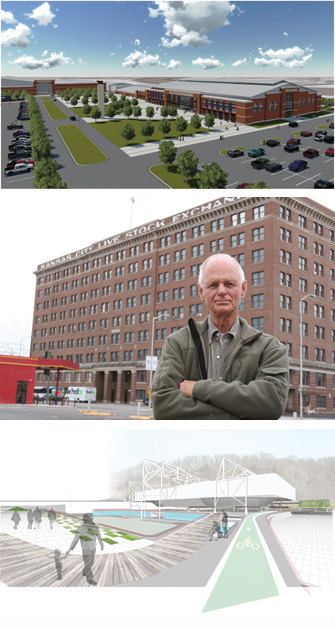

1.The American Royal wants to replace Kemper Arena with this 5,000-seat facility, which it believes would have year-round use. | 2. Bill Haw breathed new life not only into the Livestock Exchange Building, but the West Bottoms, and wants the renewal to continue. | 3. This rendering from architectural students shows a modified Kemper, roof still intact, as anchor for a unique regional entertainment venue.

The expedient thing, it turns out, is what got the city into the mess it now owns in the West Bottoms. Forty years ago, the American Royal’s plan for a facilities upgrade was co-opted by civic leaders, who piggy-backed their wish for a Downtown-area arena onto the Royal’s vision.

A 2-for-1 deal. What could go wrong?

And that is what led us to the very vacant, very underused and very expensive white elephant that we know today as Kemper Arena. Once upon a time, it helped us become major-league in ways Kansas City always wanted to be. Because of Kemper, we boasted membership in the NHL and NBA fraternities for a spell, we hosted a national presidential nominating convention, and we toasted a home-court advantage for an NCAA basketball champion.

But all of those bright shining moments were long ago, and whatever sense of community pride we felt at the time has given way to a collective regret. Because collectively, we didn’t listen to critics who said a $24 million arena built in the Bottoms would never fulfill the potential it might have Downtown. We didn’t listen to those who said the $23 million invested to upgrade it in the 1990s would never pay off. And we didn’t listen to those who said the nascent Sprint Center would doom Kemper to irrelevancy in the run-up to that $276 million palace’s debut in 2007.

So here we are today, facing a civic choice, with another chance to get it right in the West Bottoms. This time, it seems, no one wants to do the expedient thing. But that is where the consensus ends when it comes to the fate of Kemper Arena. The city is now paying rent between two views of what should be done.

One group says we’ve invested too much in it—financially and psychologically—to simply bulldoze it, an act they say would cost the West Bottoms its best chance for re-inventing itself as a retail and commercial complement to a revitalized Downtown.

The other takes a less sentimental approach, saying it would be cheaper to bring down Kemper and give the American Royal the kind of facility it wanted all along, one that could transform the organization’s ability to draw destination dollars to Kansas City.

The upside to that division? Neither approach is particularly expedient. Maybe Kansas City has learned its lesson with that kind of decision-making—after all, it’s still paying the price for that education.

But it still leaves the community with a tough decision to make: Raze it, or repurpose it?

The Royal View

For Bob Peterson, it’s not just a math lesson. Given the $1 million operating loss the city incurs with Kemper every year, and $20 million in deferred maintenance that will come due over the remaining 35 years of the Royal’s lease in the building, current and coming generations of Kansas City taxpayers are already on the hook for close to $60 million.

On top of that, transferring Kemper to another owner would trigger a $12.5 million credit from the city to the Royal, essentially refunding the private money that supporters ponied up to build the arena in the 1970s. Overall, a liability to the city’s taxpayers of more than $72 million—and that doesn’t include roughly $10 million still owed on the 1990s renovations.

But spend $5 million to bring the building down, match that amount with renovations to other American Royal facilities adjacent to Kemper, and build a $50 million dream home unmatched by any other ag show in the nation? “From a world were Kemper sits dark to a world where Kansas City would stand alone, that would be a wonderful thing,” says Peterson, the Royal’s president and CEO.

Brant Laue, a partner at the Armstrong Teasdale law firm who currently serves as the Royal’s chairman, discounts the argument that razing Kemper would be a waste of the money already invested in it. The real waste was built into this process four decades ago, when the arena was placed in the Bottoms. Laue won’t dwell on whether it was the right decision then, acknowledging simply that, “It happened.”

“But we know and see the costs for the status quo,” he firmly says. “We have an opportunity to take and convert a negative for this community into a positive and create jobs and economic activity.”

The new facility, both say, would allow the Royal to become not just an annual fall tribute to agriculture, but a year-round draw that could pump millions more into the local economy.

Laue, whose connection to ranching runs back to the family spread in Washington County, Kan., notes that there are more horses in the United States today than there were in the 19th century, when the nation depended on real horsepower to drive its agrarian economy.

That’s not a trivial development: The businesses that support America’s equestrian and pleasure-riding population, like those that underpin its livestock industry and the burgeoning animal-health corridor straddling Kansas City, all make this the ideal location, at the ideal time, for the community to reassert its agricultural heritage and its position in the agricultural economy, Laue and Peterson say, and the new facility would do that.

“The Royal is a powerful economic engine that happens every year,” Peterson says, citing studies showing a $70 million impact on the community—more than the top 10 conventions in Kansas City every year, combined. Indeed, the Royal boasts nearly a quarter-million visitors to the city each year, many of them out-of-towners who spend money quite differently—and in greater amounts—than the locals who might be drawn to the Bottoms for recreational and entertainment events at a repurposed Kemper, Peterson says.

“The economic spinoff from them would be exponentially greater from what you might get in someone who buys a concert ticket and then goes home,” he says. Part of that would come from other ag shows that the new facility would draw, because “seasonal use is not what makes this work.”

From the Royal’s office just south of Kemper, that perspective contrasts sharply with the view just two blocks to the north.

West Bottoms Resurrection

Bill Haw strides over the curb, stops, spins and bends down. He comes back up with a brown beer bottle in hand. Busch. Discarded by someone who cares a great deal less for the West Bottoms than does Bill Haw. “I hate to see that,” says Haw, drawing a bead on the nearest trash can.

Haw is the big stallion at Haw Ranches, headquartered just a horse apple’s throw from Kemper on Genessee Avenue. He came to the West Bottoms 20 years ago as CEO of National Farms, which has since been liquidated. But his ranches and feedlots across Kansas are still prospering. They crank out the money that allows him to dabble in another love: Breathing new life into the former stockyards district.

By his count, he has $10 million of his own money invested in projects around the Livestock Exchange Building, home to Haw Ranches’ intergalactic headquarters, as it says on the front door. His eighth-floor suite of offices overlooks a range of buildings in the district that have already been repurposed or are in mid-restoration.

A crown jewel in the making is in the old Drovers Telegram Daily Newspaper Building, which this savvy developer picked up for $80,000 at a bankruptcy sale. By the time he’s done restoring it to its original grandeur and adding a few flourishes, it will be worth $2 million, Haw says during a brief tour of the building. It will be home to the Bill Brady art gallery and a site for paired wine-tastings for Amigoni Winery and Vineyard, Boulevard Brewing Co. beer tastings, and office space.

Down the block, he points to redevelopment successes like the Genessee Royale Bistro, set in a former service station, the Dolphin art gallery and the R Bar, businesses that consistently draw people into a once-forsaken part of the urban core. His own plans for the area include the mixed-use Stockyards Place development, featuring the district’s first residential units, plus street-level retail.

“It was a derelict neighborhood” when he first came to the Bottoms in 1991, he said, and he derives no small measure of pride from his role in attracting such commercial anchors as Butler Manufacturing to the neighborhood. With a present footprint of roughly 30 acres, “we surround the Royal, to a great extent,” Haw notes.

His efforts to resurrect the moribund Livestock Exchange Building, 250,000 square feet of decaying office space when he got his hands on it, have paid off with a new gentrification of the West Bottoms. The building’s 100 tenant firms fill more than 90 percent of its space, and there’s a waiting list for room on the fifth floor, which he has set aside as a kind of arts incubator.

Urban renewal in any city, he says, doesn’t happen without a thriving arts community at the tip of the spear, and the Bottoms is laying claim to the next-big-arts-center mantle held for the past decade by the Crossroads District, up over the bluff to the east.

Haw’s investment—nearly as much in the area as the Royal has in Kemper itself—has given him a seat at the table for discussions about development efforts in the Bottoms, and he believes that investment would be at risk if Kemper Arena were torn down. Instead, he favors a plan developed by the Kansas City Design Studio, a project involving architecture students from Kansas State University and the University of Kansas.

Can It Be Saved?

Last year, K-State Professor Vladimir Krstic’s students at the center proposed taking the bottom “skirt” off of Kemper, removing the upper-deck seating, and leaving the suspended roof in place. That would turn it into a largely covered amphitheater for events nearly year-round, creating a recreational magnet for the metropolitan area. Soccer fields, baseball fields, riverside trails and boating access to the Kansas River, just over the levee from Kemper site, would provide the kind of recreational amenities many other urban areas have successfully developed along their rivers, proponents say.

“We need to look at the larger question of how we can improve the quality of that part of the city. That’s the fundamental issue,” says Krstic. “We think that Kemper, that southern part of the Bottoms, does not have a defined urban fabric. Kemper could become what we call the Kemper Zone, a southern node or major public space or public amenity.

“But in order for the West Bottoms to be revitalized, we have to find the programs and the facilities that are serving more than one single purpose,” he said.

The weak link in arguments for the Design Studio’s plan is that there’s no bottom line attached to it. We don’t know what it would cost to modify Kemper that way, and the scope of the class project didn’t include financing, Krstic said. Haw, however, suggests that modifying Kemper would be considerably cheaper than tearing it down and replacing it.

The Design Studio’s goal was nailing the vision for what the stockyards district could become if the focus were on drawing the broadest swath of local residents to it, Krstic said. That kind of vibrancy and energy will sustain efforts to bring more commercial, retail and residential appeal to the district, he says, much more so than a facility built specifically for the Royal.

Haw’s support for that plan is not that of a disaffected neighbor. During his time in the Bottoms, he has served as a patron, a governor and a member of the executive committee for the American Royal. But he drifted away from the organization over the years, saying it had sharpened its focus on adding exhibitors, rather than on drawing spectators, and had lost Kansas City’s interest in the process.

Kerry Amigoni, the vintner who doubles as Haw’s property manager at the exchange building, amplified those concerns, citing what she believes is a tenuous relationship between the Royal and some of its neighbors. “Detached: That’s a great word for it,” she says. “They are very internally focused; they are so excited to grow the number of exhibitors, but couldn’t care less if anyone from Kansas City, Missouri, comes and sees it. That’s the problem.”

Haw’s experience in promoting organic growth in the Bottoms—and his understanding of Kansas City development forged back when he was an executive with Commerce Bank—tells him that we’re too gullible. We buy into overly rosy projections of potential economic impact from publicly funded projects, he says, and that’s why he’s wary of the latest proposal.

“Look at the blunders we’ve made in these studies: The Power & Light District, the Downtown convention centers, the 1,000-room hotels,” Haw says. Hold onto the heritage of Kemper, he argues, build on it with a unique community amenity, and the Bottoms will continue its makeover without significant public subsidies.

The City’s Role

Haw won’t get any argument on rosy project estimates from City Councilwoman Jan Marcason. The city’s history with excessively optimistic number-crunching, she says, means the American Royal’s proposal will have to be studied in detail. But she likes the broad brush strokes, not just from her position as head of the council’s Finance Committee, but as an elective stakeholder—the arena sits in her 4th council district.

The real issue for the city, Marcason says, is whether a public-private partnership is able to make it work—emphasis on “private.” The city won’t be able to deal with the lion’s share, she says.

“The private sector needs to step up and be committed to fund-raising for at least half the cost,” Marcason said. By that yardstick, the Kemper family’s pledge to secure $10 million for the Royal’s proposal leaves a long way to go to get to the $30 million midpoint she suggests. Beyond that, Marcason said, “the city has to take a hard look and make sure what we propose is truly economically advantageous.”

Either way, she notes, the city is already on the hook for considerable sums, given the deferred maintenance costs. Even if it were able to absorb those, it would still leave the region with an arena that wouldn’t meet the Royal’s needs and would probably have outlived its useful life for attracting major concerts.

As for the long-ago decision to place Kemper where it is, Marcason’s council colleague, Russ Johnson, simply says: “Kansas City shouldn’t be too hard on itself. They made the best decision they could at the time with the information they had in hand.”

Getting to Agreement

But for too many years since then, Haw says, the city did a lousy job managing Kemper Arena, and stood by while the neighborhood went derelict. Now it has an opportunity to get this right, and he believes a multipurpose venue crafted from Kemper’s frame would serve the Royal’s needs and help fan the developmental flames in the stockyards district.

“People are coming to the neighborhood now,” Haw said. “We need to arrest the pattern of decline so that more of them will come back to the core.”

Yet that’s exactly what Peterson and Laue foresee if the Royal’s new facility is built.

“I can’t imagine that this is anything but a benefit to the community,” says Laue. He cites the kinds of ag shows that Kemper—ill-suited as it is for such events—was able to pull in over the past summer, events with no ties to the Royal.

The American Royal, says Peterson, is one of the top three agricultural shows in the country, rivaling the Denver Stock Show and the ag expo in Louisville, Ky. Those communities, he points out, are already doing their strategic planning to reposition themselves in the space where the Royal wants to be. Given that, he says it’s vitally important to move forward on the vision.

“We’re not floating ideas here,” Laue says of the specifics underpinning the Royal’s plan. “There is no facility in the world that would match this.”

Johnson, the councilman, says that if there is any way to bridge the differences between competing visions for the West Bottoms, Kansas City is forunate to have a mayor who can do it. Sly James learned the art of negotiation during his career as a lawyer, Johnson said, “and he has the ability to bring different views together and mediate those views—and to come up with a solution that everybody can live with.

Return to Ingram's November 2011